The dangers of working-class women’s football: 100 years after the English FA ban

By Kevin Skerrett

December 6, 2021 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from Socialist Project — For many sports fans in Canada, the most memorable moment of this past summer’s Olympic Games in Japan was the triumph of the Canadian women’s soccer team, a heart-stopping penalty-shootout win over Sweden that garnered them an unprecedented gold medal. For followers of the team, and especially its veterans, there was additional relish in reaching that pinnacle after having already defeated the #1-ranked US team in the semi-final, a win that arguably avenged a crushing – highly contentious – semi-final loss to the US in the 2012 Olympic semi-final.

An unquestionably stirring moment – even for those who reject the nationalism and hyper-commodification that the Olympic Games both feeds and thrives on. But the Canadian women’s soccer win could also be viewed in light of decades of social and political struggle over the rights of women to simply play ‘football’. The fact is that exactly 100 years ago today, on December 5th, 1921, England’s Football Association (FA) officially banned women from playing the game under their authority – no use of their grounds, no support from their teams, not even accessing their referees and officials.

This cruel measure had profoundly negative consequences not only for the then-emerging women’s game in England but also all across the British empire – including colonial Canada. Fortunately, a small group of social historians have been working over the past twenty-five years to unearth what socialist feminist writer Sheila Rowbotham would recognize as the “hidden history” of women’s football in WWI-era England. This work has meant that the centenary of the ban on women’s football is now being marked and recognized – in modest ways – by not only specialist historians but also the many ardent fans of today’s women’s football.

The emergence of “ladies” football

The fact that there was once such a fear of women playing football that it was actually banned and suppressed by public authorities requires some explanation. In early 20th century Britain, organized football – the game now known in North America as soccer – was a popular but almost exclusively men’s domain. While there were a few brief experiments by a handful of courageous women’s rights pioneers and suffragette campaigners in the 1880s and 1890s, the rough and tumble of football was identified as “inappropriate” for women. But WWI would bring sudden challenges to gender norms. With large numbers of men mobilized out of their jobs and their communities for the war, the labour required to keep factories operating, and to ramp up production in newly converted munitions and armaments plants was increasingly being done by hundreds of thousands of young working-class women all across the country.

By 1916, the wartime suspension of regular (i.e., men’s) league football created another vacuum. Once again, this came to be filled by the rapid establishment of new football teams comprised primarily of the women workers in the factories, and especially in the munitions works. Having women, and particularly working-class women, taking up what was previously viewed as a rough and strenuous ‘men’s sport’ was controversial. However, the games turned out to be very popular, with many attracting large crowds and paid gates raising funds for various hospital and veterans’ charities. The complaints in letters to the editor about the women’s “inappropriate” clothing was more than countered by government officials who framed the sport as evidence of the players’ sense of patriotic duty.

Before long, a “Munitionettes Cup” tournament was formally organized (1917-1918), and over the course of seven months, matches were played that attracted 10,000 spectators and more. On May 18th, 1918, the final Cup match, between Blyth Spartans and Bolckow-Vaughn’s, saw some 22,000 spectators watch Blyth win on a score of 5-0 with their star forward Bella Reay scoring three of the goals. Almost £700 was raised for a medical charity, and the match featured ceremonial participation from various public and military authorities along with officials from regional football associations. The context of the war had allowed women’s football to continue despite some ongoing social disapproval.

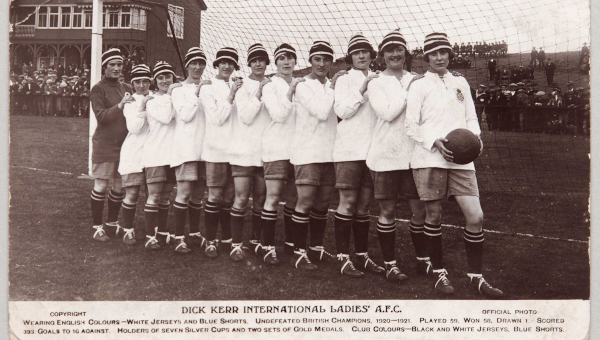

With the end of the war in 1918, things shifted significantly. Demobilized soldiers returned to their previous employment or new jobs, munitions factories were gradually converted back to pre-war production, and most of the ‘munitionettes’ and other women’s football teams dissolved. However, some of these teams wanted to continue playing. The most famous of these, from the “Dick, Kerr & Co” works plant in Preston, was known as the “Dick, Kerr Ladies Football Club.” They had particular success in the war years, and their enterprising manager began to recruit top players from other teams, forming what was effectively an ‘all-star’ team. They brought together especially talented players and began playing tours throughout England and, eventually, France and beyond. Their scoring prowess and nearly unbeaten record was widely reported in the press. Their matches began attracting large numbers of spectators: paying crowds of 15,000 and 20,000 at major football stadiums were regularly attracted, still raising funds for various health-care and war-veterans’ charities.

Throughout 1920, the popularity of these matches as well as the re-emergence of dozens of women’s football teams all over England looking to take on the Dick, Kerr Ladies, began to cause resentment from traditional football authorities that were re-establishing the regular (men’s) league play and finding that the women’s matches were sometimes outdrawing them. On Boxing Day, a match of the Dick Kerr Ladies against arch-rival St Helens at Liverpool’s Goodison Park attracted an incredible sell-out of 53,000 fans – forcing at least 10,000 more to be turned away. These matches generated a very strong interest and even began to out-draw top-level men’s matches. The authorities of the Football Association became alarmed.

The final straw: Women footballers provide support to locked-out miners

In 1921, the political and economic situation in England faced a crisis. The British economy hit a postwar downturn, and unemployment began to rise. A “rising capitalist offensive” (Melling) was launched, with the coal industry targeted first. Having nationalized the entire industry during the war in order to increase output, the British government proceeded to re-privatize its operations as of March 31. In turn, the miners’ union refused to accept wage cuts of up to 50% as proposed by the mine owners, and so, they were locked out.

Bella Reay, prolific goal scorer and a regular player in the “pea soup” football match fundraisers in support of soup kitchens for locked-out mine workers’ families; CC Photo credit Yvonne Crawford.

In several mining regions of northern England, the wartime experience with charity fundraising through women’s football matches inspired the rapid re-activation of teams in order to raise money for the soup kitchens and other provisions suddenly needed as a result of the lock-out. These teams began to play what came to be called “pea soup” football matches, which would raise funds for soup kitchens and relief programs. While not as large as the wartime ‘Munitionettes Cup’, some fifty-three different matches drew thousands of spectators and raised substantial funds (See the work of Brennan). Intriguingly, the goal-scoring star of the Cup-winning Blyth Spartans, Bella Reay, came out of her quasi-retirement after the war and began playing again in a number of “pea soup” matches (scoring frequently, once again).

According to Alethea Melling, whose 1999 article on the ‘pea soup’ women’s football matches was among the first to bring this story to light, the use of women’s football to generate material support to a group of locked-out workers provoked significant anger in the establishment, and this was expressed vehemently in Lancashire newspapers.

“The fact that ladies’ football was so closely associated with workers movements and industrial disturbances during the 1921 Lock-Out may well have added further impetus to the campaign for marginalizing the sport. ‘Pea soup’ matches may have entertained the idle masses, but they also brought together thousands of potentially revolutionary workers in areas that could be flash points for violence or provide leftist movements with an ideal opportunity to spread propaganda” (Melling p 55).

Even if these women’s football matches were not overtly political, they clearly alarmed the mining companies, the government, and many in the media. As another writer recently described it, these young women football players “were demonstrating class allegiance at the same time that they challenged gender constrictions” (Jenkel p 244). The National Football Museum suggests that the involvement of these women in the Lockout was “not well received” by the English FA, and even that they viewed it as a “last straw.”

Women’s football is banned

While the 1921 Lockout ended on June 29th, it was just over five months later, on December 5, 1921, that the English FA brought down its unprecedented edict, issuing a statement that would come to be known as the ‘ban on women’s football’. The statement they issued was widely reported in the press, hotly debated, and hugely consequential. The official arguments offered from the FA included their view that football was physically “unsuitable” for women, drawing on a long line of spurious bio-medical arguments about the weakness of women’s bodies. (Of course, no such controversy had been raised when women were asked to perform dangerous work with heavy machinery and chemicals of wartime munitions factories.)

The FA statement also included the following:

“Complaints have also been made as to the conditions under which some of these matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of the receipts to other than Charitable objects.”

No evidence for this allegation was provided, nor did the FA ever suggest that men’s matches might be subjected to such financial scrutiny. It seems obvious, in hindsight, that one of the real motivations being referenced here was the women’s football matches that had been organized to support the locked-out mine workers earlier that year – an ‘other than charitable object’ for the FA.

With this statement, the FA – whose Council was composed entirely of men – was able to suppress what it viewed as a threat to the men’s game, and a danger to the “gender order” that was in the process of being re-established. It also managed to close off a proven option for engaging in a form of class struggle. Again, Alethea Melling’s commentary highlights the political backdrop of a continuing struggle for women’s suffrage and an acceleration of socialist organizing among both men and women in the early 1920s:

“In an attempt to return to pre-war social forms, any evidence of the reordering of gender roles was attacked at every opportunity with the objective of pushing women out of male spheres back into the home…the political context of the ‘pea soup’ matches, with large groups of potentially revolutionary men and women gathering together, would have been regarded as highly dangerous given the fear of Marxism and women’s new political power” (p 51).

In this light, the polite retrospective commentary about the injustice of the FA ban in Britain’s mainstream media risks limiting and depoliticizing the narrative in a way that misses out on the even more radical class politics of this even more hidden history.

The dominion of Canada Football Association upholds “the ban”

The 1921 ban by England’s FA devastated organized women’s football and the estimated 150 teams that had just begun to take off. The ban was primarily enforced by preventing women’s teams or events access to the stadiums, grounds, and officials of all FA-affiliated teams and clubs. This pushed those teams that remained – and the hastily organized but short-lived “English Ladies Football Association” – to seek out alternative match locations at rugby grounds, public parks, and even farmers fields. This downgrade of match play infrastructure was stark, and within a year, women’s football had been driven deep into the margins. The FA ban would end up occasionally challenged and reaffirmed, and not officially rescinded until 1971 – a full 50 years later.

However, the 1921 ban did not manage to entirely eliminate women’s football. An important exception, with an interesting consequence for Canada, was the dynamic and talented Dick Kerr Ladies “all star” team based in Preston. That team and their manager were determined to defy the ban, and they set about organizing independent matches with other surviving competitors – continuing to raise funds for charities. They even played some of the first-ever women’s international matches in France.

In September 1922, the Dick Kerr Ladies team announced a tour of “Canada and the USA,” boasting of plans to play women’s teams in North America. However, on September 5th, 1922, the Dominion of Canada Football Association (DCFA) announced its opposition to women’s football and formally rejected the invitation from the Dick Kerr Ladies to help them organize a tour. (On learning this immediately on their arrival in Québec City, the team left for New York right away where they would play a successful series of matches against men’s teams.)

The DCFA was effectively endorsing the English FA’s ban, with one of its Directors (William Dean of the Ontario FA) reporting that he had seen several women’s matches played in Hamilton, and declaring it “a shame to be allowed.” Most countries of the colonial British “Commonwealth” – some with little independence and keen to prove their respect for Britain’s leadership, followed suit. While the Dick Kerr Ladies team was able to continue on their own, these decisions led many women’s teams and players to simply abandon the sport. In Britain, Canada, and many other countries, football would not return as a significant sport for women until the 1970s and 1980s.

The English ban on women’s football, endorsed by Canada’s association, also lay the groundwork for a series of similar bans and sanctions in other countries of Europe, including such football powerhouses as France (1932), Spain (1935), and West Germany (1955). Most outrageous of all was the ban on women’s football (and several other sports) that was imposed by a legal decree of the president of soccer-mad Brazil in 1941. This made it fully illegal for women or girls to play football. Brazil’s prohibition lasted until 1979.

The 100th anniversary of the English FA’s ban on women’s football invites reflection on the reasons behind it and its ongoing legacy today. The recent reconstructions of women’s football in many countries affected by the ban have been inspiring for both players and fans – witness Canada’s thrilling gold-medal victory this past summer. It has taken the work of many long-term struggles to expose and overturn these historic injustices.

But this story also reminds us that, while it was “women’s football” that was banned, it was hardly a class-neutral measure. These football players were not simply women but working-class women whose life chances had also been shaped and constrained by their class status. In that sense, as the socialist journalist Suzy Wrack has argued, while the rationale for the FA ban certainly reflected “outdated sexist attitudes” regarding what was and wasn’t suitable for women, the reasons for it were “much deeper and more political.” As an institution close to the halls of capitalist power, England’s FA had seen its interest in giving initial, careful, support to the wartime women’s football matches when the players were being heralded as ‘plucky’ munitionettes serving the imperial war effort. However, if the “pea soup” women’s football matches in support of locked-out mine workers were an indication of where things might be heading, then women’s football had become too dangerous •

Kevin Skerrett is a Senior Research Officer assigned to pensions for CUPE, and an Adjunct Research Professor at Carleton University’s Institute of Political Economy. He was a co-editor of the Cornell University Press volume The Contradictions of Pension Fund Capitalism (2018).