The Kingdom of God versus the Kingdom of Man: BA Santamaria and the origins of the Movement

By Jessica Bell, Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal

Introducing BA Santamaria[1]

“Sometimes depicted as a man totally dedicated to principle, even perhaps despite consequences, he emerges…rather as an agile political pragmatist reformulating theory to suit the purpose at hand…

“[Santamaria’s] driving will is the explanatory key which allows us to see our intrepid anti-communist crusader not so much as a grand conspirator, but as a tragic figure in the classic sense, whose own indomitable will and imagination betrayed him, seducing him into a political adventure which was bound to fail.”

– Fr Bruce Duncan[2]

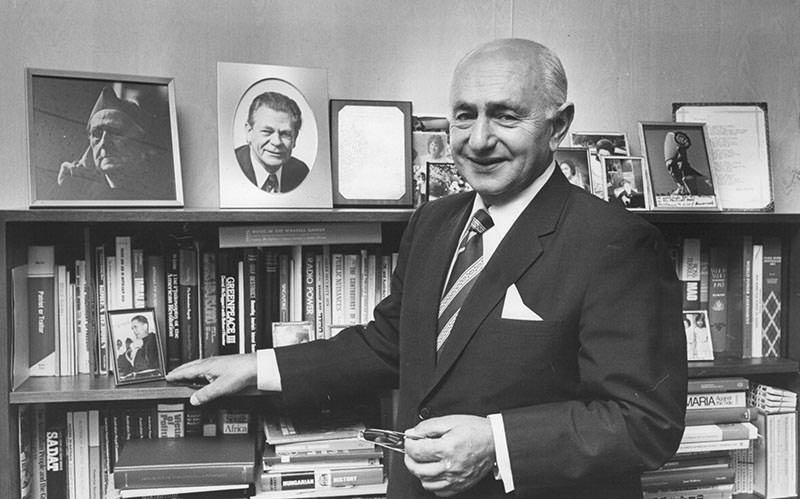

Bartholomew Augustine – more commonly just BA or “Santamaria” – Santamaria stands as one of the most impactful and provocative characters in Australian political history. He was one of “relatively few Australian political figures” to “leave a lasting impression on their country’s history and moral life”[3]: he deeply entangled himself in major historical events, especially the Labor Party split in 1954-5 and the Catholic Church near-split in 1955-7; through his political organising, propaganda writing and occasional advice to government, he would affect the political identities and careers of countless thousands; and he would come to have significant long-term influence on the social fabric of this country, especially the ideological landscape and cultural discourse.

For a man who is not notably aggressive or self-assertive, on a personal plane, he has yet managed to remain a constant storm centre, a focal point for intense organizational activity, a power-house generating a regular stream of provocative ideas, an initiator of social and political pressures, a leader who has commanded a remarkable degree of respect and loyalty from his numerous supporters…[4]

Politically, he “found his home not on the communist left or the Protestant right,” but with the “politics of Catholic revivalism.” His philosophical worldview became “crystallised [around] a distinctive version of Australian political Catholicism – which upheld the virtues of Christian piety, duty, family, work, rural community and small businesses against the vices of communism, big business, secularism and soulless modernity.”[5] His brand of “Catholic anti-Modernis[m]” was “opposed not only to materialist atheism but also to religious and political liberalism.” He advocated for a “traditional Catholicism” that believed “the path to personal salvation” to be inherently “inseparable from political action.”[6]

Over his life, Santamaria never held or pursued any position of any professional authority or prominence, be it in politics or government or other public affairs. Nor was he ever a member of any political party, major or minor. In fact, he never directly possessed any significant political or financial influence over any segment of Australia. Not only did he never come close to walking the halls of power, but he always felt segregated and alienated from Australia’s governmental, administrative and corporate elites.

Santamaria was of a different design than that of the typical politician or political organiser or publicist: he was a natural organiser and manager of resources and information; he possessed an unorthodox acumen for political competition and debate; and he wielded an overbearing force of personal character, alongside a gift for rhetorical zealotry, which could arouse allies, coax neutrals and silence enemies.

But there were many troubling elements to Santamaria’s disposition and constitution. Not comfortable with open debate, he wasn’t good at facing and responding to criticisms made against his actions and ideas. Prejudiced towards absolutes and universal laws rather than nuances and relative values, he habitually misinterpreted and mischaracterised the statements and intentions of his opponents. Tone deaf to the shrewd art of political machinations, he was prone to employing strategies of brute demagoguery and inelegant brinksmanship. He was a gifted orator, but preferred to keep himself to friendly forums that permitted his longwinded pompous monologues, rather than go to those places that facilitated debate, contest or arbitration between hostile parties. He was a competent and tidy writer, capable of carrying his account with precision and composure, but too often veered towards being speciously simplistic and oblique in his writings.

The most troubling and dangerous of Santamaria’s foibles was his tendency towards a messianic perception of himself and his work. When discussing the menace of atheistic Communism which threatened to exterminate Christian civilisation, and his own campaign to combat and defeat it here in Australia (about which we’ll learn more shortly), Santamaria spoke in extravagantly sanctimonious tones: as though he singlehandedly could identify and appreciate these existential threats for what they were, and that he alone was capable of and willing to fight them with proper gusto and grit. It was a remarkable feat of solipsism and megalomania, as though Christendom was entirely dependent on him singlehandedly saving it from imminent destruction.

Herein lies the core contradiction of BA Santamaria the political actor. Firstly, he certainly had the skills, cleverness and determination to make a substantial impact on Australian politics and accomplish grand things. But at the same time, right from the beginning, he held in his heart the seeds of intransigence, zealotry and conspiracy – which would eventually lead him to bankruptcy, recklessness and ruin.

[I]t is a measure of Santamaria’s power, whether it was of intellect, faith, character or sheer perseverance, that he was able to enlist, over so many years, so many hard-headed and promising politicians, proud prelates, dedicated priests and nuns, and so many otherwise sensible men and women in a cause which, given the realities of Australian life, could have only one inevitable result: the defeat, disarray and demoralisation of those who truly saw themselves as the Pope’s battalions fighting a war for the world in Australia.[7]

Introducing the Movement

“The Movement inevitably attracted an element whose sincerity and zeal could easily become a brand of fanaticism, spurred on by a consuming sense of mission, whipped up by the consciousness of crusade. Enthusiasm can degenerate into excesses and personal ambitions can produce spurious loyalties.”

– Tom Luscombe[8]

In the early 1940s, fixatedly believing that Australian society was in imminent peril from the terrifying menace of Communism – that the country only had a few remaining years of freedom left before it was to be horrifyingly ripped apart by bloody revolution – Santamaria founded an anti-Communist group; whose mission it was to save Australia from the Communism threat by monitoring, counter-organising against and undermining the Australian Communists as they sought to prepare the groundwork for the approaching revolution.

This was a fundamentally Catholic organisation from head to toe: its membership, newspaper readership (for the News Weekly), and wider supporter-sympathiser base were all drawn from the right-wing elements of the Catholic working class laity. The group was backed, funded, abetted and supervised by the Church authorities: the Hierarchy approved of and encouraged and supported these activities of Santamaria (although, from the beginning there was vocal opposition from a minority of priests and bishops). In terms of its formal structuration and policy orientation and operational conduct, this group would foremost act as the political wing of the Australian Catholic Church: operating on a semi-autonomous basis and acting on its own initiative and agency, but being always heavily guided and counselled and inspired by episcopal officials; interpreting civil society and political events from a distinctively Catholic analytical perspective; and always seeking to further the influence and prominence and power of Catholicism in Australian politics and society. The fusion between Santamaria’s group and the official Catholic religious authorities was so tight that “The typical Movement member at the parish level…saw his membership of the Movement as being primarily a spiritual rather than a political commitment.”[9]

It was never an especially large, powerful or wealthy organisation: its membership never went beyond a few thousand; its capital city offices employed only a basic administrative staff; it had very limited financial, human, logistical and infrastructural resources; its newspaper reach and impact wasn’t impressive when compared with its rivals (either the Catholic community press or the trade union movement press). But the Catholic Church authorities provided it with direct assistance in what ways they could: priests would energetically advertise the News Weekly from the pulpit and repeat many of the newspaper’s arguments in their sermons; bishops would provide Santamaria’s organisers with lists of young, politically-conscious working class men from within their own dioceses whom were deemed potentially suitable to be pursued as new recruits. Given this assistance, the group could artificially appear stronger and bigger than it accurately was.

The group was so secretive that it didn’t have an official name, not even for its internal documents and correspondence. It went by many anonyms, including “The Show”, “The Industrial Movement”, “The Freedom Movement”, “The Factory Group Movement”, and “The Organisation”, but most commonly was referred to as “The Movement”. In 1945, when the Catholic Church went from de facto to de jure sponsoring Santamaria and his group, it became formally known as the “Catholic Social Studies Movement”; the CSSM label became similar to a front group, for it allowed Santamaria to perform his work without suspicion or scrutiny from either Catholics or non-Catholics, hiding all his plotting and networking behind the veil of official Church business.

The Movement’s self-proclaimed rationale for existing was to oppose, disrupt and see to the eventual abolition of the Communist Party of Australia. The CPA, for the previous several years (over the 1930s), had been carrying out a plan of militant infiltration and subterfuge inside the union movement, with the ultimate goal being to trigger forth waves of industrial struggle upon the country and instigate a revolution. Additionally, “Communist control of a sufficient portion of the trade unions must inevitably mean a powerful influence within the ALP. Decisive Communist influence on the trade unions – even if it fell short of a numerical majority – meant decisive Communist influence on the ALP.”[10]

While economic sabotage was a significant objective in the Communist union strategy, the fundamental objective [of the CPA] was to use the unions not only for their own avowedly industrial purposes but through the weight of their delegations to take over the machinery of the Labor Party – its Conferences, Executives and Branches, at both Federal and State levels.[11]

To Santamaria’s chagrin, Australia’s rulers and thinkers were recklessly underplaying or downright ignoring the grim threat that Communism posed to the country’s security and perpetuity – even while the CPA was organising and radicalising masses of workers and leading large industrial strikes. He perceived that most of the social classes, political parties, government departments and civil institutions of mainstream society had become lulled into a dumbfounded state of self-confidence and self-assurance, assuming that their continued prosperity were guaranteed, while viewing the CPA as nothing more than a sideshow nuisance.

If Australia was going to be saved from the impending Communist apocalypse, and its Christian civilisation preserved and protected for the future, this would have to be accomplished by a sectional minority of the population which didn’t suffer from the same delusions and misguided serenity as the mainstream did – that is, the Catholics. Santamaria believed that it was Catholic Australians alone who could earnestly appreciate the dire situation at hand; and who would be eager and willing to do any unsavoury, unpopular actions that would be necessary to recover the situation. Seeing as how Catholics already comprised a sizable portion of the Australian working class, “What was involved … was not the interposition of an extraneous or alien force in the Labour Movement, but the mobilization of a force which was already present, but dormant.”[12]

Santamaria and his organiser collaborators (who were mostly Catholic middle class professionals) appreciated the urgent need for “a kind of Catholic ‘crusade’ against Communism; not one which would be based on mass meetings and ringing pronouncements, but one which would base itself on practical organization within the trade union movement.”[13] Santamaria envisaged a right-wing Catholic working class organisation to rival the CPA: “to build a national movement to match and, over time, better the communists at their extraordinarily effective union organising.”[14] With a dynamic and robust group like that, “the battle to defeat Communist power in the Labour Movement – whether in the Labor Party or the trade unions – [would] be essentially one of cadre against cadre, cell against cell, fraction against fraction.”[15]

Politicising Catholicism

Despite being a devout Catholic who took his religious convictions sincerely and fervently, Santamaria wasn’t ethically above using religious blackmail to advance the Movement’s agenda and interests and to help it evade criticism. Because the Movement had been endorsed by the Catholic Church, making the former a quasi-official organisation of the latter, the case could be made that “[t]o question the Movement or to oppose it was ipso facto to show oneself to be a ‘bad Catholic’ or at least an irresponsible Catholic whose thinking was out of line…”[16] Santamaria would use this fact to “boost recruitment, bolster his own authority, enforce discipline and give members a sense of being engaged in the sacred task of saving the nation.”[17]

Santamaria and his lieutenants claimed that the Movement’s particular organisational design and operational strategy was the singly true Christian way to fight Communism, to the exclusion of all others: “[T]here may be a thousand wrong ways of going about this fight, but there is only one right way – that is, His [Christ’s] way.”[18] Movement rank-and-file members were to recognise themselves as being “instruments in the Hands of Christ,” who “should treat a note from headquarters ‘as if it were signed not by a Movement executive, but by Our Lord Himself’.”[19]

[T]he Movement syllogism came to appear so plausible: Catholics must as Catholics oppose Communism; but the Movement is the only body in Australia effectively fighting Communism; therefore Catholics must as Catholics support the Movement.[20]

If the Movement was operating inside a particular workplace and a Catholic worker there refused to participate in its work, Santamaria could coerce them into compliance by suggesting that “dissent from or questioning the Movement was disloyal not just to the bishops but to Christ himself.”[21] It’s been claimed that “Hundreds of Catholics throughout Australia who refused to support the Movement, sometimes for political reasons, sometimes for religious reasons, or both, were socially ostracised and accused of being disloyal Catholics. Many were forced to change their parish.”[22]

Young Santamaria and the seeds of the Movement

Santamaria’s parents, Joseph (Giuseppe) Santamaria and Maria Costa, were Italian immigrants who came to Australia at the beginning of the twentieth century. They both were born and raised in Salina (the second largest of the Aeolian Islands, north of Sicily), coming from two separate peasant and fishing families, but had never met or known one another. After separately coming to Australia, they were to meet each other, court, marry and run a modest greengrocer’s together on Sydney Road in Brunswick (an inner north suburb of Melbourne).

BA Santamaria was born in Melbourne in August 1915. He would have five siblings, four brothers and one sister. Joseph was quite a liberal parent, tending to not use paternal authority to bully and silence his children, and instead permitted them plenty of freedoms and opportunities to speak.

These were rough, troubling times: on the one hand, the Great Depression was squeezing them financially (their family business was able to survive only thanks to tremendous sacrifice and familial solidarity); and on the other hand, sectarian-racial hatred made them feel constantly lonely, scared and besieged, as Protestant chauvinism was an ever-present terror upon their lives.

From his fledgling teenage years, Santamaria came to believe that the foundational, centrally important unit of society was the family, within which everyone had their rightful place, wherein order and security and prosperity was obtained through common obedience and regimented responsibility. “When the family – the extended family – sticks together and functions properly, it provides a large number of the social services that the individual needs to complement himself”; “Man…very much needs the social and economic clothing of the extended family.”[23]

Italy and Mussolini

“Mussolini has declared that the salvation of the world lies in the totalitarian state… He was wrong. It lies in totalitarian Catholicism. That means integral Catholicism. It means that your whole life and personality must be developed in a Catholic way.”

– BA Santamaria[24]

In the 1920s and early ‘30s, support for the Mussolini regime was commonplace and widespread among the Italian community in Australia – not out of any direct commitment to fascism as a regime and policy per se, but as an expression of general patriotism and of wanting to maintain interest and links with the goings-on of the old country. Wearing a black shirt at family and social events, for example, was an act of unspecific, ambiguous national pride (of “Italianita”), of being culturally Italian, not of holding a political ideology.[25]

Looking from the other side of the world, relying on only newspaper reports and family letters, it appeared that Mussolini had heroically brought stable, strong and reliable government back to a country that had so desperately needed it. Following the Great War, which had brought to Italy such death and devastation and plenty of poverty and chaos, “suddenly, after eleven governments that couldn’t succeed, a government came to power that … nevertheless did restore a … high degree of … political and social order for a number of years.”[26] Mussolini had seemingly saved Italy from anarchic self-destruction, and for doing this Italians across the world were profoundly grateful. At long last, being of Italian heritage could be considered a source of pride, joy and honour, rather than the hitherto object of embarrassment and ridicule.

Young Santamaria, understandably heavily influenced by his family and the wider Italian diaspora, eager to obtain some kind of Italian national identity and cultural perspective, joined in on this symphony of Mussolini adoration masked as impartial patriotism. As he later recalled, “I tended to share my father’s views since I was proud to be of Italian background and deeply resented the constant attacks on Italy and things Italian.”[27] He claimed that he grew up in an environment where “to be Italian was to be fascist.”[28]

From his teenage years onto early adulthood, Santamaria came to admire Mussolini personally (he was a remarkable “financier, statesman and idealist”[29]). He was also heartily intrigued, stirred and stimulated by many of the policies and much of the worldview of fascism. He proclaimed that parliamentary liberal democracy, which had caused both the Great War and the Great Depression, was undeniably a failure as a political system. The genius of fascism, he argued, was that it sought to heavily regulate and moderate – and thereby avoid the extreme excesses of – both free economic competition and restrictive state power. Mussolini had brought “under his control the industrial and scientific forces” of Italy and constrained “business magnates and financial mountebanks.”[30] “Thus the fascist way out of the present economic crisis was a combination of private enterprise and state control.”[31]

The problem with universal suffrage, as he saw it, was that it “does not result in the election of either the best or the wisest.”[32] By Santamaria’s judgement, “[T]here is no intrinsic virtue in political democracy which places it on a plane above more authoritarian forms of government.”[33] Conversely, “There was something holy in the idea of authority.”[34] He held up as an ideal paragon for society a kind of benevolent authoritarianism that is similar to how a family household is run: “the husband is head of the household in fact as well as in word”; the children are provided for and protected so long as they follow their father’s orders; ergo, strict obedience and good, stable governance go hand in glove; “this authoritarianism” would create “a healthy phenomenon.”[35] Seeing as how “Art, science and learning…had always flourished most under royal, imperial or dictatorial rules”, Santamaria theorised that authoritarianism was perhaps “the best form of government”, “the most viable…to which modern man could aspire.”[36]

Santamaria’s affections for Mussolini were to rapidly diminish just a short time later, in 1936. This change was not due to any of the domestic policies of fascism in Italy or of Santamaria outgrowing its ideas and values and worldview – but rather because of the brutal Italian invasion and occupation of Abyssinia. This was a step beyond where Santamaria was willing to go, and from that moment his worship for Mussolini devolved into a child-like warm but unspecific nostalgia.

Melbourne University and the Campion Society

Santamaria received a Catholic primary and secondary education: St Ambrose Parish School, St Ambrose’s Primary School, St Joseph’s, and St Kevin’s College. He would always speak warmly of his religiously-oriented learning: “they inculcated a set of religious and moral values which sustained generations in their belief as Christians. To their lasting credit, they insisted that faith must be validated by reason, placing a high premium on the intellectual foundations of both religion and morality.”[37] Santamaria’s first experience of secular education came when he attended Melbourne University to study law.

Shortly after beginning his university studies, Santamaria came to the conclusion that the entire higher education system was biased, misguided and sectarian: Catholics were being rendered a marginalised, isolated, disparaged minority. Across secular academia, all elements and features of thinking, knowledge and logic were entirely framed in favour of a Protestant perspective, favouring the “Whig interpretation of history” and the “philosophical liberalism of the Enlightenment.”[38] This was a disastrous state of affairs for Christian standing: Protestant liberalism, by favouring a materialistic view of history that relegated God to an abstract concept rather than an interventionist subjective agent, was effectively popularising atheism by stealth – and, by the logical extension of atheism, it was indoctrinating its students in Marxism (“with its vision of an earthly paradise this side of the grave, and its categorisation of religion as the opiate of the people”[39]). By the end of his investigation, Santamaria came to hold an entrenched, fervent hostility to secular universities which, “under the guise of impartiality”, “put across the materialist interpretation of history which is not only an unproven hypothesis but fundamentally opposed to the ideas on which European civilisation is founded.”[40]

Scores of young Catholics like Santamaria were coming into tertiary education during this time only to find a “hostile intellectual environment.”[41] They startlingly “discovered that the intellectual foundations of faith which were adequate to the protected enclave of the Catholic school were utterly inadequate in a new and hostile intellectual environment”; the philosophical and theological fundamentals and presuppositions for their views were being treated by professors and scholars with doubt at best and animosity at worst. Upon realising that “their intellectual equipment was inadequate to the task of meeting the Marxist challenge, and that they had no access to any means whereby they might fill the gap in their general knowledge”, these young Catholics believed they needed to teach themselves what they were missing, and to develop new concepts, knowledge and arguments for defending and promoting their faith in this intimidating academic setting.[42]

In 1931, the year before Santamaria came to Melbourne University, a student Catholic study group called “the Campion Society” had been founded by eight intellectually-frustrated but motivated young men.[43] It had an active membership of around 40. Its agenda was to discover, comprehend and openly popularise an intellectual, scholarly defence of Catholicism; as well as to translate their ancient religious truths into practical social ideas for the modern time. Their reading focussed on writers such as Hilaire Belloc, GK Chesterton, Christopher Hollis, and Christopher Dawson; these were predominantly English Catholics and intellectuals in the secular sense. They especially wanted to find ways to rebut the beliefs and arguments of popular far left writers like HG Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and Beatrice and Sidney Webb.

The Campions were “a new type of Catholic undergraduate – brash, positive, self-confident, and animated with zest and conviction”; they advocated for a Catholicism that “was argumentative in a Chestertonian-Bellocian style, consciously intellectual, firmly based on a more than cursory glance at history, literature, and theology, and above all, socially committed.”[44] They were “triumphalist Catholics in the true sense. They were proud of the religious and cultural inheritance which many of them had just discovered and they were prepared to proclaim their faith far and wide.”[45] The Society made its presence known and felt, and immediately became a serious, respected feature of campus life. Historian Colin Jory writes (with perhaps a little exaggeration), “For some eight years, from 1931 to 1938, [the Campion Society] exerted an influence unparalleled by that of any other Catholic lay association in Australia’s history.”[46]

By the time Santamaria had joined it, towards the end of 1932, the Society was looking for strategies and schemes to leave its university ghetto and to spread its arguments, ideas and historical insights into the wider Catholic community. In Santamaria’s own words, the Society should seek, “To hammer Catholicism into an impregnable fortress on which heresy will shatter itself [and to] mould the one and a half million Catholics of Australia into an organic reality ready to resume the Catholic offensive.”[47]

The Spanish Civil War

Following the outbreak of the civil war in Spain in mid-1936, Catholic community and episcopal leaders sought to employ it for their own political purposes. Ignoring the major bulk of available information coming from international news reports, which depicted the civil war as being more complicated and nuanced and difficult to understand, they instead narrowed their attention almost exclusively on reports of anti-Catholic terrorism occurring in Republican-controlled areas: far left mobs allegedly prowling the streets, murdering Catholics (both laymen and clergymen), and razing churches and other holy buildings. The Catholic leaders concentrated on the select details that described Catholic suffering so transparently; demarcating Spanish Catholics as a uniquely oppressed, terrorised people, and the far left as murderous, depraved ruffians:

Images of death and destruction committed by ‘savages and Communists’ were contrasted with Franco’s crusade to restore the position of the Church and protect the interests of Spanish workers. A vast propaganda effort was unleashed by the Catholic press to galvanise working-class Catholic opinion firmly against the Republican struggle…

The Australian Catholic community was fed a diet that depicted the conflict in terms of a battle between good and evil. Franco was God’s warrior sent to defend Catholic Spain. All who opposed this view were enemies, Communists, Freemasons, Liberals, Protestants.[48]

The Campion Society, by now led by Santamaria, joined in on this shrill sensationalistic panic campaign. It proclaimed that a crusade was being waged by the Spanish far left to eradicate Catholicism from Spain: driven by a vindictive and depraved atheism, the Republican movement had declared war on God and was seeking to drown it in blood. The Campions took the position that protecting the Catholic Church held foremost priority above all other factors. While they did not idolise or identify with Franco personally (they were certainly not unaware that he was a vicious despot), they were however broadly sympathetic with the Nationalist rebels and their mission to overthrow the Republic. In this perilous life-or-death struggle for the future of Spain, they asserted that a victory for the Republicans would entail the creation not of a liberal democracy but a Soviet colony with Stalinist policies and impulses: this regime would immediately carry forth the complete extermination of Catholicism in practice and thought across Spain. A catastrophic tragedy like that was something, however, that wouldn’t and couldn’t possibly happen if Franco won the civil war – because the Spanish Catholic Church was actively aiding and supporting him. From that perspective, Australian Catholic commentators and newspapers advocated for a “lesser evil” policy of qualified support for Franco. According to Santamaria’s judgement,

a Nationalist victory over the Republicans was…the least disagreeable outcome of the available options… [I]t mattered little that General Franco was a destroyer of elected governments and a despot, or that he had sought, and received, support from Hitler and Mussolini. During the Spanish Civil War, the Catholic Church was under attack, and Santamaria was going to defend Christ the King.[49]

However, whenever the Campions tried to publicly advocate for this perspective, they were confronted with “an almost unbroken wall of hostile opinion” from the Australian thinking and activist milieus. Santamaria put this down to the “deep cultural roots in the English Reformation, the Spanish Armada, the Whig interpretation of history, and the left-liberal ethos dominant in Anglo-Saxon communities from the early years of the twentieth century.”[50] The Australian pro-Republican left embodied, he continues,

the confused complex of liberal-Marxist ideas which have been dominant in the West since the days of the French Enlightenment, with their implicit belief in the perfectability of man and society on this earth, if only the Left were given a free hand with the social and political engineering. What we [pro-Nationalists] represented was a less Utopian view of man, with a profound belief in the Fall and in Original Sin; imposing the necessity of the search for justice, but knowing that the quest for human perfectability on earth was ultimately unrealizable and would be used to justify the most appalling tyrannies. The perfection of man, if it could be achieved, was not for this life, and, as far as concerned the next, it depended on the maintenance of the intimate link with God, which was what the religious freedom denied in Republican Spain was about.[51]

The Spanish Civil War was the watershed moment for Santamaria’s political development and identity. Events in Spain had forecast that “in the years immediately ahead all established beliefs would be called into question and that in many countries Christianity would be destroyed by Communist persecution.”[52] This necessitated Santamaria becoming an anti-Communist activist: “concentrat[ing] all [his] physical and intellectual energies on the Communist problem.”[53] He writes,

After the Spanish debate…everything was changed. Beforehand, the Campion experience was predominantly an adventure of the mind. It was Spain which imported passion into the enterprise. From it originated the belief that so long as the Soviet Union existed, not only religion, but the liberal culture of the West, reflected in its free political institutions, was in daily jeopardy; and that if the battle was not won within the institutions of individual nations, the world would one day face a major conflagration.[54]

Catholic Action

After graduating from Melbourne University with his law degree, Santamaria was in a position to leave political-religious activism behind and enter the legal profession, but this wasn’t what he ended up doing. When Archbishop of Melbourne Daniel Mannix offered him a job within the Catholic Church’s public network, where he would be doing religiously-focussed activist work on a professional full-time basis, he accepted it immediately; “It did not even occur to Santamaria to turn this offer down.”[55] A special project was underway inside the Church, so Santamaria had been personally scouted by Mannix, and the young man was only too eager to get involved.

Since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the Catholic Hierarchy had been pursuing a pro-Nationalist agenda, making the case to their flock about how Christian civilisation across the globe was facing its gravest challenge ever in the form of Communism, and that only by holding tightly and passionately onto one’s Christian principles could the moral rot of Marxism (disguised as secular modernity) be stopped.

During this time, the fluid, multi-class, diverse, unstructured mass of the Catholic laity had become bisected by the Spanish controversy: one half, believing foremost in the principles of democracy and justice and freedom, were avidly supportive of the Republican Government; the other half, taking an approach that prioritised tradition and order and servitude, were championing Franco and the Nationalists.[56]

This was causing much consternation among the Hierarchy: despite their strident and fervent warnings about the tangible, alarming, rising danger that Communism posed to Australia, this wasn’t being immediately translated into a surge of right-wing, chauvinistic, anti-Communist vigour among the congregation.

Quite clearly, some sort of a new, special campaign was needed to redress this situation. Returning the laity to a respectful, attentive and obedient state, and bringing them back under the control, direction and guidance of their priests, would require more than simple moralism-ridden, doctrinal-soaked haranguing. It would need to be an active, open, participatory campaign; one that didn’t demarcate and ghettoise laymen and laywomen, but rather encouraged them to openly engage and partake in mainstream Protestant-secular Australian society; “[T]he Hierarchy was now making a distinct call for Catholics to play a role in what was termed ‘the apostolate of institutions’ – ie to take an active part in community life.”[57] And it would need to be one that also enriched the inner life and culture and spirit of the Church, that made the laity proud and happy and joyous by their faith. This campaign would be based somewhat on the Campion Society: encouraging a prideful, intellectual, outwardly assertive promotion and defence of Catholicism, intervening into society and making a mainstream appeal for Catholic social values, ancient morals and divine truths. This campaign was to be called “Catholic Action”.

In order to better supervise and artfully guide these lay grassroots activities, the Church wanted to establish a national leadership body – managed by a staff comprised of laypersons, but overseen closely by the Hierarchy – that would coordinate, administrate and shepherd the Catholic Action activism from all across the country, in all the different parishes and sectors of civil society. This body would be called the Australian National Secretariat for Catholic Action (ANSCA).

At first, Santamaria was appointed the assistant secretary, but shortly thereafter was promoted to acting head secretary. From that moment on for the next decade, “the name of Santamaria was linked with practically everything that was happening” in Catholic Action.[58] He was now one of the most powerful, well-known and respected laymen in Australian Catholicism; he was in charge of a national office full of resources, contact networks, and prominence. In time he would use this power and access to pursue a particular agenda: he believed that Catholic Action “should take the offensive and become the effective leaders of all Australians, irrespective of their religious affiliation”, rather than remain on the defensive and merely to “concern itself with providing protective organisations for Catholics, to be sure that they will not be tainted by the corruption of the world around them.”[59] Santamaria declared that working class Catholics must become “the apostolate of communal charity,” which included criticising and redressing such evils as “immorality, filthy working conditions, Communism, the exploitations of their fellow worker, the corruption of younger workers.”[60]

But Santamaria had an unspoken, underlying political project which he was actively working towards: he sought to use Catholic Action as a vehicle to realise “the total political mobilisation of Catholics.”[61] He believed that passive contemplation and intellectually-agnostic inquiry were “almost a criminal waste of time in the revolutionary situation with which the Church is faced”, and thus “unless Catholic Action genuinely aims at the creation of a Christian social order by means of large scale action in the social, economic, political and cultural spheres, we are wasting our time.”[62] Unless Catholics take command over civil society and thereby create a Christian social system, “the apostles of hatred will take the world over and destroy it.”[63] In his role as secretary for ANSCA, “Santamaria was up-front, impatient for action and quite uninterested in theory – a leader in search of a following.”[64]

"Santamaria suggested that there was a place for organisations of lay Catholics using political means to further the religious and moral interests of the Church, acting on their own responsibility but “united with the Hierarchy” and “effectively” under its control… Santamaria’s position was that the defence of the Church’s purely spiritual or religious interests…often involves direct political action; therefore the Church is entitled to enter the political sphere to achieve its religious aims. Thus, presumably, to defend herself against Communism the Church could set up a political party and use the means of party politics. And this in turn could mean that in certain cases a party could claim to be the Catholic party and so claim the allegiance of all Catholics “under pain of sin”.”[65]

The emergence and rise of the Movement

There was no single point in time or space whereupon the Movement was founded. Rather, the concept of “the Movement” – as a collective, centralised network of right-wing, anti-Communist Catholic unionists – arose into existence through organic interest and impromptu necessity. Then with time, it underwent various phases of evolution, centralisation, growth and coalescing. Only later were those individuals, contacts and collective bodies formally solidified and cohered in a recognisably organisational form, with Santamaria as its head organiser.

In the mid-to-late 1930s, a number of Catholic Labor politicians and political operators like Herbert Cremean and Arthur Calwell began speaking about the urgent problem of Communist infiltration inside the union movement and the ALP. Cremean argued that “the Federal Labor leadership was at all stages unwilling, and the State Labor machine apparently incapable” of mounting an anti-Communist purge campaign. He maintained that “[w]hat was needed was something quite different from those nonsensical anti-Communist organizations which publish a manifesto, fly a flag, run a few demonstrations, and engage in ritual denunciations which do little other than expose the ignorance of the organizers.” Cremean wanted to find ways of easily making contact with right-wing Catholic workers in those Red-captured unions, such that he might work with them to remove the elected Communist leadership and bring the union back under democratic (ie Labor) control. To accomplish this, “it became necessary to devise an organizational structure which would both raise the recruits and keep them in the field.”[66]

For the next few years, anti-Communist union organising occurred on a spontaneous ad hoc basis, where Catholic professionals and non-workers like Santamaria, Cremean and Frank Keating would offer their assistance in organisation, connections and resources to those Catholic unionists who were seeking to fight against and remove their elected Communist leaders.

The test case of this was in 1942 with the Australian Railways Union at the Newport rail workshops. JJ Brown, “a young, energetic and capable Communist”, “had recently been elected State Secretary of the [ARU].” In response, “a group of Catholic railwaymen, headed by Jack Desmond”, approached Santamaria requesting his assistance. They needed propaganda material with which to criticise and undermine Brown’s leadership. So Santamaria researched, wrote, published and printed a monthly newspaper, Rail Worker, for the right-wing railway workers to read and discuss and share up and down the rails.[67]

From 1941 to ’43, Cremean and Santamaria tried to organise collective meetings of right-wing Catholic unionists, so that these temporary, spontaneous collaborations could be formalised into a coordinated, professional form; the eventual goal was to have something that looked like a genuine political organisation. The first meeting of this kind gathered together only 4 people (Santamaria and Cremean and two others, Frank Hannan and Stan Keon); the second had just 20. But the third meeting had some 300 attendees: this assembly sanctioned an aggressive anti-Communist platform, and established the trade union and workplace organising cells which were to become the operational nexus of the Movement.

During this same period, Cremean and Santamaria had numerous meetings with Archbishop Daniel Mannix, the purposes of which were to request financial assistance from the Church. They “outlined their concerns about Communist penetration of the labour movement.”[68] The archbishop became convinced about the urgency and dangers of Communism, and was impressed by their earnestness and eagerness, and he agreed to give them £3,000.[69] Santamaria also requested from Mannix his assistance with finding suitable recruits among the Catholic laity; again agreeing to help out, Mannix assembled together the priests from across Melbourne and asked each of them to nominate the names of suitable young, conservative working men from their parishes who could potentially be approached by Santamaria and convinced to join his group.[70]

By the middle of the 1940s, Santamaria believed that the foundations for the organisation had been constructed and solidified, and thus it was now possible and necessary to expand the Movement to much larger, higher fields. He approached the entire Church Hierarchy leadership and requested that they formally sponsor the Movement. In a series of memoranda written to the collective Australian bishops, Santamaria described the hypothetical future Hierarchy-backed Movement as “an arm of the hierarchy in the battle against communism, constitutionally subject to the control of the bishops.”[71] “We are at last in the position that we have a national organisation which is as strongly disciplined as the Communist Party,” he wrote; “This is a strong weapon in the hands of the Hierarchy to ensure the triumph of Christian ideals and values in the Australian environment.”[72]

The bishops resolved to endorse the bulk of Santamaria’s plan and request for funding; they “committed them[selves] to support, control and fund Santamaria’s anti-Communist organisation.”[73] The Movement was to be formally named the Catholic Social Studies Movement. In all matters of constitutionality, macro policy and finance, the CSSM would be supervised and guided by a Hierarchy-liaising committee of bishops (the Episcopal Committee on the Catholic Social Studies Movement, ECCSSM); only on matters of strategic policy, rhetoric and daily management would the CSSM’s lay membership retain its autonomy and independence.

Modelling the Movement on the CPA

In his documents explaining the rationale and objective of the Movement, Santamaria talked about how the CPA’s most remarkable and unique achievement was its phenomenal growth over a relatively short period of time, going from tiny grouplet to mass party in a single generation. It had worked clandestinely inside the trade union movement through the deployment of autonomous cells; significant portions of its activities were not publicly known or admitted to; and its rank-and-file members wouldn’t be able to know of the actual scope and scale of its operations or broad strategy. “Unity of policy and organization was guaranteed by the application of the principle of ‘democratic centralism’, which ultimately guaranteed control by the party bureaucrats, and through them, by agencies of the Soviet Government,” Santamaria explained.[74]

As he was sketching out his organisational blueprint for the Movement, Santamaria came to the realisation that, “The Communist organizational method had stood the test of effectiveness, and my proposal was that we should copy it.”[75] The CPA were the proven experts at unionism, and so the only way to beat them was to become better than them at their own game. This could only be done by replicating the CPA’s organising methodology and using it against them. In the first annual report of the Movement (written in 1944), Santamaria explained that “we intend to found a disciplined national organisation which will be modelled completely on the Communist Party and which will work on the same principles of organisation.”[76] He went so far as to call for the Movement to wholesale replicate the organisational program of “democratic centralism” based on a centralised leadership; authoritarian policies and directives; requiring rigorous discipline from members; and secretive cells, contacts and networks.

From its earliest days of conception and construction, the Movement was to be a strictly covert organisation; it would operate on a confidential basis; “Secrecy was at the core of Santamaria’s plan: not just keeping his organisation secret from the outside world, but running its far-reaching operations clandestinely.” Every aspect of the Movement’s internal structure, policy-making processes and organisational mechanics were to be judiciously hidden and safeguarded. “A central plank of Santamaria’s conception was that Show members had to be carefully screened and handpicked for this clandestine crusade, pledging never to reveal its existence to anyone outside the ranks, let alone speak publicly of its work.”[77]

Admission to the meeting was by production of a letter of invitation. The meeting had the atmosphere of a conspiratorial gathering rather than a gathering of the saviours of the commonweal…

The basis of the Movement’s power was the parish ‘cell’, which met under conditions of tight secrecy. Doors were locked, and I [Paul Ormonde] have heard of one Melbourne meeting where windows were blacked out to give the impression that nothing was happening in the meeting hall. Meetings were almost invariably held on parish premises. Cell members were carefully selected and once in the meeting hall were pledged to secrecy. No names of leaders of the central organisation were given. No letterhead paper was used in communications.[78]

To many well-meaning people who were recruited into the Movement and had the chance to see the organisation from the inside, “Santamaria’s operation struck them like that of an Italian godfather, benignly exercising influence from above yet not accountable through normal democratic methods. Bonds of personal loyalty and patronage were highly important.”[79]

The Industrial Groups

The scale, stakes and terrain of the union struggles between the CPA and its opponents began to expand exponentially in 1945-7 when the Labor Party launched its own political intervention into the trade union movement. This was called the “ALP Industrial Groups”: they were to be a collective network of Labor-supporting unionists, “for the purpose of strengthening the cause of the Australian Labor Party in factories and workshops”, advocating policies and positions in line with the ALP, running in union elections to get Labor-friendly officials elected; and they would seek “to keep a close liaison with trade unionists and workers in industry on behalf of the Labor political movement.”[80]

But the central aim of the Groups was to undermine and weaken the CPA’s power and stature from across the union movement – and to eventually bring those Communist-run unions back under Labor Party control.

The underlying principle on which the Industrial Groups were founded was that the Labor Party would form ‘groups’ – not ‘branches’ – inside Communist-controlled unions; and that these groups would select and give the equivalent of official Labor endorsement to candidates to oppose the Communist leadership in ways similar to the endorsement of Labor candidates in Federal and State elections.[81]

Upon learning of their existence, Santamaria was eager for Movement members to join the Industrial Groups and contribute to them; and for a kind of coalition to organically arise between the Movement and the ALP. Being a small organisation of only limited resources and no wider notoriety, comprised of conservative Catholic workers who did most of their union work as isolated individuals, the Movement could only ever make a limited and minor impact upon the national union battlefield.[82] By joining and participating in the Groups, thereby operating underneath the banner of the ALP, Movement activists could take advantage of Labor’s name, recognition and popular trustworthiness; they could obtain a veil of legitimacy and authority under which to do their union work; in a confidential memorandum, Santamaria explained that, “Today we have the cover of the Labor party. They carry on the fight as the executives of these factory ‘discussion groups’ and none can effectively question their bona fides… That will provide the Movement with the same kind of insurance everywhere.”[83] And the Movement could gain access to a far larger and wider audience for their anti-Communism advocacy than otherwise.

But it became quickly apparent that the primary problem with getting the Groups launched and operational and genuinely combative was the lack of suitable, committed cadre. This problem was rectified thanks to the intervention of the Movement into the Groups. Numerically-speaking, Movement members encompassed only a minority of the overall Groupers, between 25 and 30 percent, but they were able to become the Industrial Groups’ main infantry forces.

A division of labour arose inside the Groups: all of the formal decision-making power remained in the hands of the Labor-backed officials, while most of the tedious, laborious and thankless unionism work – the heavy-lifting, distance-travelling and door-knocking to make the organisation function and prosper – was performed by Movement members. Despite being only “energetic, zealous minorities within the Groups”, “Movement members obviously were influential”, and they formed “an efficient pressure group in support of status and backing for the Industrial Groups.”[84] With hindsight, Santamaria boasted that “there can be little doubt that the Groups owed a great deal to the dedicated enthusiasm of Movement members.”[85]

Careful, Icarus

From 1945 to the early ‘50s, the Industrial Groups’ method of undermining and disempowering Communist union officials was repeatedly proven successful, as they “expelled the Communists from one union after another”; “By 1950 the Communists were in full retreat, and the Industrial Groupers were everywhere advancing ”[86]

The CPA’s influence and connections with the union movement was spiralling downwards:

The sunset of 1953 saw the Industrial Groups triumphant over the Communists in many unions both large and small. The major victories were in the Federated Clerks Union, the Federated Ironworkers’ Association, the Amalgamated Engineering Union, certain branches of the Australian Railways Union, the Boilermakers’ Union, Waterside Workers’ Federation, Builders Labourers’ Federation, Electrical Trade Union, Printers’ Union and the Amalgamated Postal Workers’ Union.[87]

The same can also be said of the political wing of the labour movement, as CPA penetration and activity inside the ALP evaporated: “[T]he Communist Party, at present moment, cannot hope to seize control of Australia by revolutionary means,” Santamaria wrote to Mannix in 1952; “[T]he Communist grip on the political Labor movement has been broken.”[88] The Industrial Groups had “scored enough significant victories” that they’d “broken the Communist ‘stranglehold’ on the Australian trade union movement.”[89]

Despite the battles in the unions being so dirty and egoistic and vicious, Santamaria recognised “the fact … that by the beginning of 1953, Communist power was to all intents and purposes broken in the Australian trade union movement”; the future was exciting, because once and for all “Communist power could be beaten in a clean-up operation.”[90] By 1953, “[Santamaria] was at the peak of his influence, within both the Catholic Church and the Australian political system.”[91] He began flirting with the possibility of retiring from active politics entirely.[92]

The Groupers were becoming an ever stronger, more prominent, more cohesively organised faction within the trade union movement and the Labor Party, and consequently the activities, personnel and policies of the former were having a significant impact on the culture, networks and organs of the latter two institutions. The Groupers were appropriating a considerable segment of Labor Party territory, beginning first with the ALP’s internal governing bodies – by 1953-4, “Industrial Group supporters had the numbers on the two biggest ALP State executives – those of New South Wales and Victoria”[93] – and then advancing on to the elected public politicians. Following the 1949 election, “a brigade of [Movement] members and fellow travellers” came into the federal Labor caucus, “[h]eaded by the flamboyant and virulently anti-communist Stan Keon and Jack Mullens.”[94] All of a sudden, a sizeable minority of Labor MPs in federal and Victoria state parliament were now Grouper-aligned or even Movement sympathetic.

The Industrial Groups had been a remarkably successful project. Much of the credit for this belonged to “the high level of commitment and close attention to detail of Show members and their allies,” the work of whom included “the preparation of well-constructed, hard-hitting propaganda and meticulous organisational effort…” The Movement had become a “well-organised cadre of Catholics who had transformed the ALP’s factory groups into a reliable and cohesive anti-Communist force.” This was all thanks to “the vision, inspirational rhetoric, driving force, and authoritarian leadership displayed by Santamaria.”[95]

In a state of jubilation, Santamaria went so far as to boast that, “In one sense, therefore, the Social Studies Movement has fulfilled its immediate task.”[96] Intoxicated by these enormous victories and this breathtaking momentum, he began reassessing and redesigning the objectives, rationale and constitution of the Movement for the future. Until this time, he formulated, the Movement had been solely a defensive project, aimed at blockading and terminating the Communist advance. But now, with the “Red menace” subdued, scattered, scared and lost, and with the Movement enriched with authority, resources, manpower and money, it was now potentially possible to redirect the organisation towards a proactive, constructive agenda. “[T]here is no reason why the Social Studies Movement should not be able to do far more for the public welfare in the future than it has been able to achieve in the past.”[97]

He devised that the Movement – by operating inside the Industrial Groups – could potentially begin to influence, direct and shape the ALP itself, such that the organisational composition and policy program of the latter would begin to shift to correspond to the political philosophy and worldview of the former. As early as September 1950, Santamaria had written in a memorandum of his hope that soon “the programme of the ALP will be in harmony with Christian Social teaching”[98] – and now it seemed that that time had arrived. Internal Movement documents from 1951-3 attest that “Santamaria aimed to determine public policy and to replace the Labor leadership with Movement associates and sympathisers.”[99] In a letter to Daniel Mannix in late 1952, with the CPA virtually vanished, Santamaria outlined this new strategic direction that the Movement ought to take:

The Social Studies Movement should within a period of five or six years be able to completely transform the leadership of the Labor Movement, and to introduce into Federal and State spheres large numbers of members who possess a clear realisation of what Australia demands of them, and the will to carry it out. Without going into details, they should be able to implement a Christian social programme in both the State and Federal spheres, and above all, to achieve coordination between the different States in so doing. This is the first time that such a work has become possible in Australia and, as far as I can see, in the Anglo-Saxon world since the advent of Protestantism.[100]

But Santamaria wasn’t going to have the opportunity to formulate these extemporaneous notes into concrete policies, let alone practically redeploy the Movement in order to pursue them as a plan. His prophetic vision of the future would go unrealised, as the winds of history changed direction and Australian society was pushed down a very different route to the one he had predicted and hoped for. His messianic mission to take control of the Labor Party and impose upon it a Catholic social program – with which to transform Australian society wholesale – was going to implode upon itself almost immediately after he had been precariously erected it.

A nationwide scandal and partisan brawl was about to break out: under Doc Evatt’s direction, the federal leadership of the ALP was to disband the Industrial Groups, with thousands of Grouper members and supporters either being expelled from the party or resigning in protest; effectively resulting in the Victorian branch of the ALP being chopped into two halves.

The Movement’s infiltration of the ALP branches – albeit with mainly traditional Labor voters – caused considerable bitterness against the Church. A sectarian backlash was inevitable once it became known that a Church-sponsored body had been secretly manipulating a great multi-religious party.[101]

And Santamaria, the erstwhile ingenious theatre director, was to suffer a ghastly humiliation: being dragged onto stage and into the spotlight without a mask or weapon; his script and stage notes no longer able to shield him; his players either abandoning him or being disempowered alongside him; the audience seeing him in all his bare, pathetic mediocrity and his sly, creepy mischievousness; being mercilessly scorned and degraded and shamed by them; and everything he worked towards and built being wrecked and burned all around him.

Future historians will, most likely, make two charges against Bob Santamaria. Firstly, he will be held responsible for destroying the long association between the Australian Labor Party and the Catholic Church and, secondly, perhaps more seriously, he will be accused of splitting Australian Catholics themselves into two strongly opposed camps.[102]

Conclusion

BA Santamaria’s political career and worldview was foremost guided and shaped and determined by his anti-Communism, with all his other policies and strategies and arguments corresponding to it accordingly. And yet, if there was anything about Australian politics that he failed to analyse, comprehend and recognise in an accurate and lucid manner, it would surely be that of Communism itself. This is the chief tragic irony of Santamaria: his greatest strength turned out to be, in actuality, his greatest weakness.

In truth, Santamaria never bothered himself with conducting an honest, sober, detailed, nuanced critique of Australian Communism: what it was and wasn’t capable of doing; what it was and wasn’t trying to accomplish; how it interpreted and understood Australia and the world; how it theorised, analysed and strategically-oriented itself to the trade union movement and the Labor Party; and so forth.

Instead he opted for a doomsday, diabolus ex machina version of Communism which was grossly simplistic and absurdly exaggerated: “To listen to Movement propagandists was to hear that the gates of hell would prevail against the Christian Church and that the triumph of Communism was inevitable. And in the climate of fear that they generated, anyone who questioned this assessment was either soft-headed or a crypto-Communist.”[103] Shrill hysteria about the ever-growing, ever-approaching danger of Communism became a habit that Santamaria struggled to resist. He was depicted by some as “a highly vocal publicist dominated by an impending catastrophe syndrome. He was never really happy unless predicting a crisis around the corner or doom under the noon-day sun”[104]; he “possessed a crisis mentality. He saw a looming disaster where another would have identified a developing problem.”[105]

Either through rank opportunism or a capricious mind or a malicious intent, Santamaria was never satisfied with confining his definition of a “Communist” to that of someone who was a member of the CPA; or who subscribed to the doctrine of Marxism; or who greatly admired Stalin’s Russia and sought to replicate it in Australia. Concepts, definitions and labels were kept fluid and unstable in Santamaria’s mind, resulting in him being able to think shapelessly and to freely discriminate on conceptual preferences and terminological categories, thereby allowing him to rearrange the formula as per his personal discretion. Effectively, anyone at anytime could be labelled by him as being a Communist. Over the history of the Movement, a plethora of Labor politicians who were in any manner or at any moment supportive of particular left-wing policies or were in any way associated with the Left faction of their party – including the likes of Arthur Calwell, Ben Chifley and Doc Evatt – would be accused of being a Communist fellow-traveller or sympathiser or enabler. Santamaria had clearly fallen ill with the disease of anti-Communist neurosis: of accusing anyone and everyone who opposes him, just out of reflex, of being a secret advocate of Communism.

But most damning and contemptible of all, Santamaria was never honest and wholehearted about being a genuine anti-Communist; so the one thing that he possessed a niche gift for was, in actuality, a charade and fraud. Communism was merely a bogeyman and rhetorical prop employed to further his political agenda and career: to gather power and money and influence under his autocratic, centralised authority; to scare and morally blackmail well-intentioned people into obedience and silence; to employ flagrantly and dishonestly in retrospect as justification for his earlier foolish actions; and to be used to legitimise his claims and proposals for future policies when actual facts and evidence weren’t readily available.

Santamaria sought to use anti-Communism as a vehicle through which he could obtain his one true ultimate goal: the political revival of Catholicism. “His real focus…was not on the communist enemy, but on the ‘enemy within’,” which he saw as “the collapse of Western civilisation caused by ‘corruption from within’.”[106]

What Santamaria was railing against…was modernity itself. What he favoured was a return to the past – a past in which Catholic social, moral, and religious precepts formed the basis of the kind of society and economy that contained “the ultimate truths and principles by which it is worth living”. What had replaced this and had now to be overturned was the victory of “the humanist revolution” caused by “the assault on the principle of authority” and the corruption of the legal and educational systems…

… [U]nder Santamaria’s leadership The Movement embraced a kind of feudal Catholicism that nostalgically saw small landholding agrarianism as central to a simple life based around a fundamental, traditional Christian society founded on the family unit, turning its face against the powerful secularising forces that became predominant in the decades after World War II.”[107]

Santamaria’s crusade against modernity, secularism and Protestantism-cum-Marxism was a lifelong project; he would be still fighting and arguing and organising against these evil forces right till his death. But he would never again possess the kind of power, influence and respect that he had in the years immediately before the ALP split. And his secret, underlying project of Catholic political activation would remain unrealisable and utopian, for never again would there come a time when that dream might potentially be turned into a reality through Santamaria’s guiding leadership, bombastic rhetoric and spiritual zeal.

Notes

[1] My deepest, warmest gratitude to Naomi Farmer for assistance with an earlier draft of this article.

[2] Duncan 2001, pp393, 406.

[3] Manne 1998, p168.

[4] Luscombe 1967, p178.

[5] Manne 1998, pp168, 169.

[6] Paul Strangio and Brian Costar, “BA Santamaria: Religion as Politics,” in Costar, Love and Strangio 2005, p202.

[7] Fitzgerald 2003, p290.

[8] Luscombe 1967, p187.

[9] Ormonde 1972, p21.

[10] Santamaria 1981, p68.

[11] Santamaria 1981, p67.

[12] Santamaria 1981, p76.

[13] Santamaria 1981, p74.

[14] Aarons 2017, p2.

[15] Santamaria 1981, p75.

[16] MJ Charlesworth, Forward to Ormonde 1972, pXIV.

[17] Duncan 2001, p404.

[18] [Father Harold Labor,] Into Thy Hands quoted in Ormonde 1972, p21-2.

[19] [Father Harold Labor,] “A Summary of the doctrinal basis of the Catholic Social Studies Movement; provisionally approved and authorised by the Episcopal Chairman” quoted in Duncan 2001, p126; emphases in original.

[20] MJ Charlesworth, Forward to Ormonde 1972, pXIV.

[21] Duncan 2001, p405.

[22] Ormonde 1972, p122.

[23] Santamaria quoted in Fitzgerald 2003, p8; ellipsis in original.

[24] [Santamaria,] Orders of the Day quoted in Duncan 2001, p17.

[25] See Duncan 2001, p15.

[26] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p57.

[27] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p15.

[28] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p54.

[29] Farrago quoted in Duncan 2001, p16.

[30] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p51.

[31] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p16.

[32] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p16.

[33] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p54.

[34] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p16.

[35] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p54.

[36] Russel Ward quoted in Fitzgerald 2003, p27; first ellipsis added, second ellipsis in original.

[37] Santamaria 1981, p8.

[38] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p34.

[39] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p34.

[40] Santamaria quoted in Ormonde 1972, p6.

[41] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 2015, p34.

[42] Santamaria 1981, p12.

[43] Named after Edmund Campion, the English Jesuit martyr of the sixteenth century who was killed by Elizabeth I. “The founding members were Frank Maher, Denys Jackson, John Merlo, Murray McInerney, Gerard Heffey, William Knowles, Frank Quaine and Arthur Adams”; Santamaria 1981, p14.

[44] Luscombe 1967, pp179-80.

[45] Henderson 1983, p11.

[46] Jory quoted in Henderson 1983, p13.

[47] Santamaria quoted in Fitzgerald 2003, p20.

[48] Fitzgerald 2003, pp35, 36.

[49] Henderson 2015, p76.

[50] Santamaria 1981, p36.

[51] Santamaria 1981, p37.

[52] Santamaria quoted in Ormonde 1972, p6.

[53] Ormonde 1972, p66.

[54] Santamaria 1981, p38.

[55] Manne 1998, p169.

[56] See Fitzgerald 2003, pp40-1.

[57] Henderson 1983, p69.

[58] Luscombe 1967, p183.

[59] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 1983, p28.

[60] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p71.

[61] Duncan 2001, p397; emphasis added – JB.

[62] Santamaria quoted in Henderson 1983, pp30, 28.

[63] Freedom quoted in Duncan 2001, p79.

[64] Henderson 2015, p165.

[65] Max J Charlesworth, Forward to Ormonde 1972, pXVI; emphasis in original.

[66] Santamaria 1981, p74.

[67] Santamaria 1981, pp74-5.

[68] Fitzgerald 2003, p58.

[69] “Mannix’s relationship with the Movement appears to have resembled that which might exist between an aged patriarch and favoured grandchild: indulgent and solicitous of the youngster’s wants while benignly neglectful of its behaviour”; Paul Strangio, “The Split: a Victorian Phenomenon,” in Costar, Love and Strangio 2005, pp25-6.

[70] See Fitzgerald 2003, p59.

[71] Duncan 2001, p82.

[72] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p81.

[73] Duncan 2001, p82.

[74] Santamaria 1981, p75.

[75] Santamaria 1981, p75.

[76] Santamaria, “Report on Anti-Communist Campaign,” early 1944, in Morgan 2008, pp126-7.

[77] Aarons 2017, pp2,4. For the text of the pledge, see “Pledge,” mid-1940s, in Morgan 2008, p140.

[78] Ormonde 1972, pp17, 20.

[79] Duncan 2001, p400.

[80] Duffy 2002, p50.

[81] Santamaria 1981, p98.

[82] “The results were quite apparent, even if not of overwhelming importance”; from 1943 to ‘45, the Movement was able to claim “a considerable number of anti-Communist victories in small- and medium-sized trade unions”; Santamaria 1981, p76. “The Movement had won many of the small craft unions, but the powerful mass unions remained firmly in communist hands”; Duncan 2001, p70. On the scale of Australian national politics and industrial unionism, however, it was still small, under-resourced and ineffectual. Although it had the ability to wrestle in a fair contest with the CPA in many workplaces and unions, the Movement was nowhere near large enough to even be noticed by either the ACTU or the ALP.

[83] Santamaria quoted in Fitzgerald 2003, p73; emphases in original.

[84] Duffy 2002, p50.

[85] Santamaria 1981, p101.

[86] John Douglas Pringle quoted in Santamaria 1981, p114.

[87] Duffy 2002, p61.

[88] Santamaria, Letter to Archbishop Daniel Mannix, 11 December 1952, in Morgan 2007, p74.

[89] Ormonde 1972, p56.

[90] Santamaria 1981, p115.

[91] Henderson 2015, p207.

[92] See Duncan 2001, p185.

[93] Ormonde 1972, p56.

[94] Paul Strangio, “The Split: a Victorian Phenomenon,” in Costar, Love and Strangio 2005, p28.

[95] Aarons 2017, pp35,36.

[96] Santamaria, Letter to Archbishop Daniel Mannix, 11 December 1952, in Morgan 2007, p74.

[97] Santamaria, Letter to Archbishop Daniel Mannix, 11 December 1952, in Morgan 2007, p75.

[98] Santamaria quoted in Duncan 2001, p156.

[99] Duncan 2001, p407.

[100] Santamaria, Letter to Archbishop Daniel Mannix, 11 December 1952, in Morgan 2007, p75.

[101] Ormond 1972, p38.

[102] Luscombe 1967, p191.

[103] Ormonde 1972, p160.

[104] Luscombe 1967, p198.

[105] Henderson 2015, p162.

[106] Aarons 2017, p204.

[107] Aarons 2017, pp205, XV.

References

Aarons, Mark 2017, The Show: Another Side of Santamaria’s Movement, with John Grenville, Scribe.

Costar, Brian; Love, Peter; and Strangio, Paul (eds) 2005, The Great Labor Schism: a Retrospective, Scribe.

Duffy, Gavan 2002, Demons and Democrats: 1950s Labor at the Crossroads, Freedom Publishing.

Duncan, Bruce 2001, Crusade or Conspiracy?: Catholics and the Anti-Communist Struggle in Australia, UNSW Press.

Fitzgerald, Ross 2003, The Pope’s Battalions: Santamaria, Catholicism and the Labor Split, with Adam Carr and William J Dealy, University of Queensland Press.

Henderson, Gerard 1983 [1982], Mr Santamaria and the Bishops, Hale & Iremonger.

Henderson, Gerard 2015, Santamaria: A Most Unusual Man, The Miegunyah Press.

Luscombe, Tom 1967, Builders and Crusaders: Prominent Catholics in Australian History, Lansdowne Press.

Manne, Robert 1998, The Way We Live Now: The Controversies of the Nineties, Text Publishing.

Morgan, Patrick (ed) 2007, BA Santamaria: Your Most Obedient Servant: Selected Letters 1938-1996, The Miegunyah Press.

Morgan, Patrick (ed) 2008, BA Santamaria: Running the Show: Selected Documents 1939-1996, The Miegunyah Press.

Ormonde, Paul 1972, The Movement, Thomas Nelson.

Santamaria, Bartholomew Augustine 1981, Against the Tide, Oxford University Press.