The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia: achievements and limitations

[This talk was presented at the Laborism and the radical alternative: Lessons for today conference, held in Melbourne, Australia, on May 30, 2009. It was organised by Socialist Alliance and sponsored by Green Left Weekly, Australia’s leading socialist newspaper. To read other talks presented at the conference, click HERE.]

* * *

By Verity Burgmann

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was established in Australia first in Sydney in October 1907, two years after the founding of the IWW in the United States in June 1905 in Chicago. Known as the “Wobblies’’, the IWW was a revolutionary industrial unionist organisation. It preferred this terminology to “syndicalist’’: while it acknowledged much in common with European revolutionary syndicalism, it proposed a less decentralised industrial organisation. It maintained that: workers should be organised on the basis of the industries in which they worked rather than on the basis of their particular craft or trade skills; ultimately all workers should come together in One Big Union, which would take over control of production, distribution and exchange from the employers; and this process, while revolutionary could be non-violent, because if all workers were already in One Big Union, its power would be so great that the change to a new socialist society could be achieved peaceably.

The IWW had developed due to dissatisfaction with craft unionism, which was seen to pit workers against each other and make it easier for employers to control and exploit all workers. Its emergence was an intelligent response from within the labour movement to the increasing centralisation of capital and industry; it aspired to present a concentration of labour power to meet a concentration of ownership of capital.

However, strictly speaking, only waged workers could join, so there was a serious limitation from the outset: it was a very “blokey’’ organisation. Female paid workers were very welcome, but working-class homemakers could not officially join. Female industrial militants were applauded—but patronised—in the IWW song “Rebel Girl’’. “To the working class she’s a precious pearl. She brings courage, pride and joy, to the fighting Rebel Boy.’’ Far more impressive was the IWW’s principled hostility to racism as an ideology and practice that divided workers at the point of production that must be combated at all cost. Within a labour movement seriously implicated in endorsement of the White Australia Policy, the Australian Wobblies stood out for their persistent opposition to racism.

In 1908 the IWW movement in the USA split: those most contemptuous of political parties packed the convention. Debate centred on the Preamble, which stated:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace as long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until all the toilers come together on the political as well as on the industrial field, and take and hold that which they produce by their labor through an economic organization of the working class without affiliation with any political party.

The rapid gathering of wealth and the centering of the management of industry into fewer and fewer hands makes trades unions unable to cope with the ever-growing power of the employing class because the trades unions foster a state of things which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping to defeat one another in wage wars. The trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

These sad conditions can be changed and the interests of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries, if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.

The “non-politicals’’ successfully moved a resolution that deleted from the Preamble the sentence commencing “until all the toilers come together on the political as well as on the industrial field’’ and substituted in its place “until the workers of the world organise as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system’’. The minority group still supporting political action, associated with the Socialist Labor Party under Daniel De Leon, withdrew and established separate headquarters in Detroit. The larger “non-political’’ section remained based in Chicago and became the more successful movement.

This split was replicated in Australia. In May 1911, the Chicago IWW was established, first in Adelaide, but the Sydney branch, or Local as it was called, became the largest and most significant. As in the United States, it was the Chicago non-political IWW that was the more famous in Australia. It became what is generally known as “the IWW’’, though the political IWW minority remained organised in the IWW Clubs, closely aligned with the Socialist Labor Party of Australia.

There were many links between the American and Australian Wobblies, helped particularly by the movements of workers between these continents, especially maritime workers. Not just seafarers, but many radicals roamed around the world quite freely at this stage. Unlike today, there were few restrictions on movement. There were no passports. It was quite common for agitators and activists to spend several years working and agitating for better pay and conditions for workers in one country then to move on to another country. Sometimes these agitators moved on because their efforts to improve conditions for workers brought them into trouble with local authorities. Often the radical labour movement in the country in which they arrived would know about them before they appeared, because of the newspapers produced by each movement, which reported on the movements in other countries.

One example of someone who moved around the Pacific area was John Benjamin King. King, born in Canada in the 1870s, worked as a miner, a teamster, and a stoker. There were many baseless rumours about King, for example, that during his time in Chicago he had blown up a newspaper office. During1910-1911, he worked as an IWW organiser for Vancouver. After the August 1911 Vancouver strike was broken, he worked his way to New Zealand as a stoker. In Auckland, his economics class had an enrolment of 30 miners and achieved notoriety. It was rumoured they studied the techniques of industrial sabotage. “The less you work’’, he told one meeting, “the longer you will live’’. But no member would testify when interviewed by police. However, with questions being asked about him in parliament, King fled to Australia in 1912, where he became a leading figure in the Australian IWW. Because of this, in October 1916, he was given ten years jail for printing and distributing 25,000 pounds worth of forged five pound notes—along with my grandfather’s first cousin, the process engraver who made the plates. The idea was to debase the currency to help bring down capitalism and finance Wobbly propaganda in the meantime. King’s sentence was reduced to two years, because he was less involved than my relative.

King was representative of the many personal links between the radical labour movements in countries on the Pacific rim, which helped the process of transplantation of the IWW from its country of origin. These transplants adapted to local circumstances. The Australian IWW was therefore different in significant ways from the American IWW. It did not slavishly follow all the American trends, debates, and schisms, as American IWW historiography has tended to assume of the IWW Locals that appeared in other countries. In fact, intriguing contrasts emerged between the IWWs on the two sides of the Pacific Ocean, which merit separate attention.

1. Opposition to political action

In the USA and Canada, political action was not so much a practice to be rejected as a matter of principle but an irrelevancy, because those to whom the IWW appealed were largely estranged from the electoral process. The American IWW, while rejecting control by political parties, never expressly condemned political action and many American Wobblies were active members of parties such as the Socialist Party.

It was very different situation here, where there was universal manhood suffrage (including indigenous Australians) from 1856 and payment for politicians from 1871, and then universal adult suffrage by the end of the 1890s in most States and federally from 1902 (excluding indigenous Australians until 1962). All adults, except Aboriginal Australians, could vote in elections in every part of Australia from the beginning of the twentieth century. Australia a white democracy, with Labor parties viable because of this democratic status, many years before the USA with a significantly better-developed economy. Moreover, electoral registration was compulsory in Australia. Not only was it relatively easy for itinerant workers to secure electoral registration; they were fined if they did not.

These democratic features caused the early existence of Labor parties in Australia, and Labor parties that were politically precocious. During the most successful years of the Australian IWW, the Labor Party was in government federally in 1908-09, 1910-1913 and 1914-1917. It was also in government for much of this period in most of the six States. In Australia, therefore, the IWW not just abstractly anti-political as in the United States and Canada but empirically so. It argued from experience that Labor parties did not help workers much.

The behaviour of Labor governments seemed to confirm IWW warnings against political action. Direct Action, the Australian IWW newspaper, had a running commentary on the futility of political action, sell-outs and betrayals by Labor MPs, their huge salaries and perks, and so on. For example, on May 1, 1914, Direct Action announced: “Workers of Australia, you have raised up unto yourselves gods, in the shape of Labor politicians, and behold events have proved that their feet are but of clay.’’ On June 15, 1915, Direct Action claimed that the actions of the NSW McGowen Labor government, such as strike-breaking, should “serve as a warning to the working-class, not alone of this country but of the whole world’’. Its famous song, to the tune of “Yankee Doodle’’, is still sung today by trade union activists suspicious of Labor MPs:

Come listen, all kind friends of mine,

I want to move a motion,

To build an El Dorado here,

I’ve got a bonzer notion.

Bump me into Parliament,

Bounce me any way,

Bang me into Parliament,

On next election day.

Some very wealthy friends I know

Declare I am most clever,

While some may talk for an hour or so

Why, I can talk for ever.

I know the Arbitration Act

As a sailor knows his ‘riggins’,

So if you want a small advance,

I’ll talk to Justice Higgins.

Oh yes I am a Labor man,

And believe in revolution;

The quickest way to bring it on

Is talking constitution.

I’ve read my Bible ten times through,

And Jesus justifies me,

The man who does not vote for me,

By Christ he crucifies me.

So bump them into Parliament,

Bounce them any way,

Bung them into Parliament,

Don’t let the Court decay.

Less well known is another Australian IWW creation, also to “Yankee Doodle’’, which commences:

The politician prowls around,

For workers’ votes entreating;

He claims to know the slickest way

To give the boss a beating.

Polly, we can’t use you, dear,

To lead us into clover;

This fight is ours, and as for you,

Clear out or get run over.

The advanced nature of the political labour movement in Australia enabled the IWW to build support from amongst disaffected Labor voters, based on actual evidence about the performance of Labor representatives. So the Australian IWW, operating in a country with a comparatively democratic franchise and compulsory electoral registration, was more expressly and truly anti-political, a stance informed by the experience peculiar to Australia of Labor governments

Although limited by its own strict rules that only “wage-slaves’’ could join, the IWW at its highpoint around 1916 probably had a membership of about 2000. Direct Action sold 15,000 copies weekly during the highpoint of IWW influence, some authorities claim as many as 26,000. Certainly, it was read possibly by 50,000 each issue as copies were invariably handed from worker to worker. All in all, its influence far exceeded its membership base.

What sort of people became Wobblies? They were workers of all sorts, especially lesser skilled workers. They lived in cities, towns and country areas. A common element in the IWW both sides of the Pacific was the unskilled itinerant worker, especially in the bush and backwoods. A typical Wobbly was a “hobo’’, to use the North American terminology. However, the economic, political and social position of the hobo was significantly different on the two sides of the Pacific. In North American accounts, the hobo support base of the Wobblies is presented as a social aberration; the IWW constituency was isolated from workers organised by the American Federation of Labour (AFL), because it was predominantly unskilled, unorganised and un-British, itinerants largely ignored by the official, highly exclusive labour movement.

In Australian society, by contrast, the hobo was normal and the itinerant bush worker the backbone of union politics. Itinerant workers were not neglected by Australian unionism as their equivalents were by the North American labour movements. Rather, they were amongst its strongest participants and were especially active in the new unions formed late in the nineteenth century.

The high standing of itinerant workers in Australia reflected the difference between Australian and North American economic structures: Australia was primarily an extractive and large-scale grazing economy absolutely dependent on the labour of itinerant workers; North America was a more industrialised economy in which transient workers played a vital but far smaller role. So the “nomad’’ was respected within the Australian labour movement. The nomadic rural worker was even seen as the “typical’’ Australian with typical national characteristics. Accordingly, the Australian IWW was much more in tune with stereotypical national characteristics than its American progenitor. Arguably, Australian culture was more Wobbly than North American. For example, the rude language of the Wobblies became part of labour movement argot. Their capacity to be heard within the labour movement and even beyond it was particularly facilitated by the extent to which they were seen as representing the militants amongst a certain sort of worker with an esteemed place within both the labour movement and Australian society.

3. Dual unionism versus ‘boring from within’

This was a debate that was central to the IWW strategy wherever it appeared around the world: whether to set up a separate set of unions in competition with the existing more conservative ones or whether IWW supporters should stay inside these existing unions and build up support with a view to eventually encouraging enough workers to join the One Big Union. In the USA and Canada, “boring from within’’ was largely futile because the American union movement was very craft-oriented and conservative so Wobblies created new unions in competition: created a dual union structure.

The Australian IWW had little choice but to “bore from within’’ because the union movement in Australia was very strong at this time. Dual unionism remained a long-term aspiration, but not an immediate tactic (with the partial exception of Broken Hill where the Barrier Industrial Council recognised an IWW membership card as equivalent to a union card); so they bored from within with propaganda about the need in due course for building from without.

This significant departure from North American IWW practice was an adaptation to Australian circumstances. New unions of semi-skilled and unskilled workers had developed from the 1870s onwards, and it was these new unions that became the backbone of the labour movement, working cooperatively with the older craft unions but in many ways outflanking them as the locus of power within Australia’s relatively unstratified labour movement. In 1916 union density was 47.5 per cent in Australia and only 12.2 per cent in the USA. The Australian IWW was operating in an environment where the labour movement was extremely well-organised industrially by international standards. So the Australian IWW was not aiming to organise workers neglected by trade unionism like the American; instead, it was hoping to improve the basis on which workers were already organised.

Wobblies criticised craftism and sectionalism, and in particular the emergence of a trade union bureaucracy, especially when it was better remunerated than the workers it serviced. But their arguments were mounted from within. Wobblies were almost always members of established trade unions. Wobbly support subsisted in networks of militancy within mainstream trade unions. Jimmy Seamer, a mining industry unionist of the time, told me in 1985 shortly before he died: “You met Wobblies wherever you went ... All militants followed the Wobblies ... They had a foot in everywhere.’’

Military intelligence files located at the Australian Archives in Canberra also contain observations that IWW theories had “struck deep into the militant unions’’.

In boring from within, Australian Wobblies secured considerable protection. Australian employers could not easily isolate and physically intimidate Wobblies, because they worked under the cover of a strong trade union movement that in Australia had the added respectability of sponsoring one of the two alternative parties of government. Where American Wobblies were confronted physically by employers and their thugs, Australian Wobblies were simply hemmed in by the trade union movement itself.

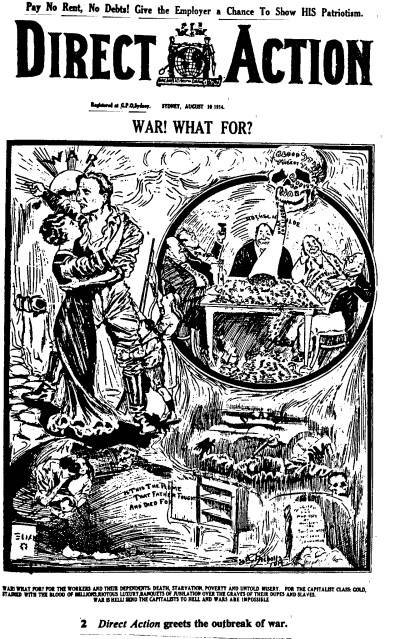

The US IWW did not directly interfere with the US war effort. By contrast, in Australia, no organisation opposed the outbreak of the Great War as promptly and vociferously as the IWW. The front page of Direct Action for August 10, 1914, declared:

WAR! WHAT FOR? FOR THE WORKERS AND THEIR DEPENDENTS: DEATH, STARVATION, POVERTY AND UNTOLD MISERY. FOR THE CAPITALIST CLASS: GOLD, STAINED WITH THE BLOOD OF MILLIONS, RIOTOUS LUXURY, BANQUETS OF JUBILATION OVER THE GRAVES OF THEIR DUPES AND SLAVES. WAR IS HELL! SEND THE CAPITALISTS TO HELL AND WARS ARE IMPOSSIBLE.

On August 22, leading Wobbly Tom Barker urged: “LET THOSE WHO OWN AUSTRALIA DO THE FIGHTING. Put the wealthiest in the front ranks; the middle class next; follow these with politicians, lawyers, sky pilots and judges. Answer the declaration of war with the call for a GENERAL STRIKE.’’ In 1915 Barker was charged with publishing a poster prejudicial to recruiting, which exposed the hypocrisy of the warmongers, by proclaiming: “To Arms! Capitalists, Parsons, Politicians, Landlords, Newspaper Editors and Other Stay-At-Home Patriots. Your country needs YOU in the trenches!! WORKERS, Follow your masters.’’ Barker argued in court this was a serious attempt to encourage recruitment, but was found guilty. In 1916 he was sentenced to 12 months jail for publishing an anti-war cartoon by Direct Action cartoonist, Syd Nicholls, one of many such superb cartoons published by the IWW; but the release campaign in Barker’s defence was so strong that the authorities released Barker after only a few months.

The Australian IWW was aware of the danger of anti-war activity distracting it from organisation at the point of production and inviting government repression, the considerations that had prompted American IWW caution in relation to the war. But it threw itself wholeheartedly into campaigning against the war and Australian involvement. In so doing, it increased its opportunities to organise at the point of production, because its anti-war activity won it many supporters amongst workers inclined to be critical of the senseless slaughter—and increasingly so as time went on. By November 1916, Labor Prime Minister Hughes, a long-time opponent of IWW influence within the labour movement, was complaining that the IWW was “largely responsible for the present attitude of organised labor, industrially and politically, towards the war’’. The threat of conscription in 1916 and 1917 gave the IWW an even greater opportunity to have its voice heard. It expanded rapidly in this period. Great crowds used to come to IWW anti-conscription meetings, up to a sixth of the population of Sydney gathering around and trying to hear the speakers, as Tom Barker recalls in his memoirs.

When three-quarters of the Labor politicians in federal parliament indicated they would refuse to pass a Conscription Act, Prime Minister Hughes blamed the IWW and announced it needed to be attacked “with the ferocity of a Bengal tiger’’. The ultimate fate of the IWW in Australia was sealed by Hughes’ desire to rid the labour movement of all IWW influence.

The manner of the Australian IWW’s demise was different from that of the North American IWW. The repression of the Australian IWW was carried out by the right-wing of the labour movement—the Labor Party in government—because it constituted a far-left opposition to the right-wing of that movement. So the Australian IWW did not endure beatings, lynchings and torture by individual loyalists as in the USA—but Labor government-sponsored suppression, in advance of US criminal syndicalism legislation, seriously weakened it. The Hughes National Labor government enacted the Unlawful Associations Act on December 19, 1916, under which any member of the IWW could be imprisoned for six months.

In the next few months, 103 Wobblies were imprisoned, usually for terms of six months with hard labour, and many more were sacked from their jobs. Twelve foreign-born Wobblies were deported; at the same time, United States authorities were shipping some American Wobblies to Australia. The ships passed each other in the Pacific. Twelve Wobblies in Sydney were also framed up late in 1916 and charged with “treason-felony’’ – levying war against the King, allegedly by plotting to burn down Sydney. The court case was not conducted fairly. There was a lot of newspaper hysteria, unfair reporting and the police acted wrongly in many ways to secure the conviction of the twelve Wobblies. They were sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from five years to fifteen years with hard labour.

However, the wider labour movement objected to the treatment of the IWW by the federal government. The labour movement, the trade unions in particular, staged a huge campaign to release these men. The release campaign spread outward from the Wobblies themselves to all manner of labour organisations: trade unions; labour and trades hall councils and regional industrial councils; left-wing parties; and even sections of the Labor Party. The state Labor government in New South Wales, where the Twelve had been jailed, investigated the court case and eventually decided there had been a miscarriage of justice and the Wobblies were all released by late 1921.

So the labour movement, whose more right-wing political representatives had suppressed the IWW, was also responsible for releasing the Twelve. This proved the degree to which the strategy of “boring from within’’ had enabled Wobblies to become accepted as a legitimate part of the wider labour movement. The IWW’s strength on the ground, the degree of support it had engendered for militant action at the point of production, enabled it to push the mainstream labour movement into action in its defence.

What happened to the Wobblies? Part of the mythology surrounding the early days of the Communist Party is that large numbers of Wobblies realised the error of their syndicalist ways and joined. In fact, very few Wobblies joined the Communist Party in the 1920s. The Communist movement throughout the world was anxious that Wobblies renounce their revolutionary industrial unionist past and join the Communist parties; it urged them to do this in January 1920 in The Communist Internationale to the I.W.W.

The Australian Communist Party made elaborate overtures to Wobbly remnants.

Many Wobblies reacted with enthusiasm, initially, to the October Revolution, believing that it heralded not the rule of a party but of the working class. However, doubters amongst the Wobblies became considerably more numerous as Bolshevism consolidated itself after victory. Many of the small number of Wobblies who joined the Communist Party did not stay members for long. They were coming from an elaborately democratic and open organisation, so they were astounded by their reception within the Communist Party as it began implementing the authoritarian and hierarchical forms of organisation for which it became renowned.

One Wobbly who became critical of the Communist Party he had joined was John Benjamin King, with whom we started our story. He was involved in establishing a Wobbly cell within the Communist Party called the Industrial Union Propaganda League (IUPL) in 1921. According to a resurrected Direct Action on December 1, 1921, the IUPL urged workers to return to industrial organisation: “We must make up for the lost time that the working class of this country has been cheering the revolutions of other countries and not putting its own house in order.’’

The Communist Party expelled King and the others on charges of syndicalism and forbade any Communist Party member to join the IUPL. The IUPL became the Industrial Union Propaganda Group (IUPG). The IUPG argued the Communist Party was now like the Labor Party, the concern for political processes representing an obstacle in the way of militant direct action and the formation of revolutionary industrial unions.

Lecturing for the IUPG, King criticised the Communist tactic of “capturing the machinery’’ of the unions. When the Communist president of the Labour Council asked: “then how can we expect to capture the more powerful machine of the capitalist state?’’, King replied: “One doesn’t want to capture a mad dog before shooting it.’’ All in all, IWW-type militants remaining within the Communist Party were discouraged. Those who remained had to stop being Wobblies.

The IWW kept making organisational reappearances during the 1920s—in Melbourne, Perth, Sydney and Adelaide, sapping the strength of the Communist Party branches. Not until the early 1930s did the Communist Party assume a role more significant and most IWW branches were disbanded. By the early 1930s the Communist Party world vision had triumphed over the Wobbly ideal of a society free of leaders and politicians of all kinds, but the battle between these competing forms of revolutionary working-class politics was protracted. The Communist Party wanted former Wobblies to join, but only Wobblies tired and beaten, without any syndicalist life left in them. The party resented the fact that Wobbly ideas maintained a tenacious hold on the minds of many militants.

When J.B. King rejoined the Communist Party in 1930, he was sent immediately to the Soviet Union for six years for re-education. His return in 1936 was nicely timed, just when needed to justify the new united front tactic to those still inclined to Wobbly ideas. After his return to Australia in 1936 he eulogised the Soviet experiment in a speech on 8 November in the Friends of the Soviet Union Hall in Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald was delighted that an IWW man, who had advocated go-slow methods, had become “a Fast Worker in Russia’’, a hero of the Five Year Plan for producing twice as much as expected while superintendent of a Russian coal mine. He had wanted the workers to produce “in less than Johannesburg time’’, but the antiquated machinery had broken down in the attempt. However, J.B. King’s reprogramming at the hand of Soviet authorities was only briefly effective. King soon became disillusioned all over again with the Communist Party and he departed, explaining he simply did not believe in it any more.

Given the demise of Communism and the acknowledged shortcomings of the social democratic/Laborist project around the world, the lost cause of the IWW is worth reconsidering, if only to examine its critique of the labour movement ideologies and practices, of Communism and social-democratic Laborism, that triumphed over it.

The distinctive characteristics of the Australian IWW that differentiate it from its North American parent—especially the hostility to parliamentary action to achieve social transformation—make its experience peculiarly relevant to labour movement activists today in countries where politicians increasingly control labour movements. There are many aspects of Wobbly political practice still relevant to modern existence. Particularly in a world characterised by increasing connections of corporate power around the world, the IWW model of much closer forms of organisation of the world’s workers, but in an ultra-democratic way, is a useful model for international labour movement organisations.

Notes

This talk is based on material I have published in the following works, which provide full referencing:

Verity Burgmann, Revolutionary Industrial Unionism. The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia, CambridgeUniversity Press, Melbourne, 1995.

Verity Burgmann, “The Iron Heel: The Suppression of the IWW during World War I’’, in Sydney Labour History Group (ed.), What Rough Beast? The State and Social Order in Australian History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1982, pp. 171-191.

Verity Burgmann, “Antipodean Peculiarities: Comparing the Australian IWW with the American’’, Labor History (USA), Vol. 40, No. 3, August 1999, pp. 371-392.

Verity Burgmann, “The IWW in International Perspective: comparing the North American and Australasian Wobblies’’, in Julie Kimber, Peter Love and Phillip Deery (eds), Labour Traditions. Papers from the Tenth National Labour History Conference, University of Melbourne, 4-6 July 2007, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Melbourne, pp.36-43.