Let us begin this attempt at recovered memory by sketching the main setting for the tale. Manchester, it must be said, was a poor choice of exile for a young man whose left-wing convictions had so concerned his family. It was the greatest and most terrible of all the products of Britain’s industrial revolution: a large-scale experiment in unfettered capitalism in a decade that witnessed a spring tide of economic liberalism. Government and business alike swore by free trade and laissez faire, with all the attendant profiteering and poor treatment of workers. It was common for factory hands to labor for 14 hours a day, six days a week, and while many of them welcomed the idea of fixed employment, unskilled workers rarely enjoyed much job security.

Living conditions in the city’s poorer districts were abominable. Chimneys choked the sky; the city’s population soared more than sevenfold. Thanks in part to staggering infant mortality, the life expectancy of those born in Manchester fell to a mere 28 years, half that of the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside. And the city still bore the scars of the infamous Peterloo Massacre (in which cavalry units charge unarmed protesters calling for the vote) and had barely begun to recover from the more recent disaster of an unsuccessful general strike.

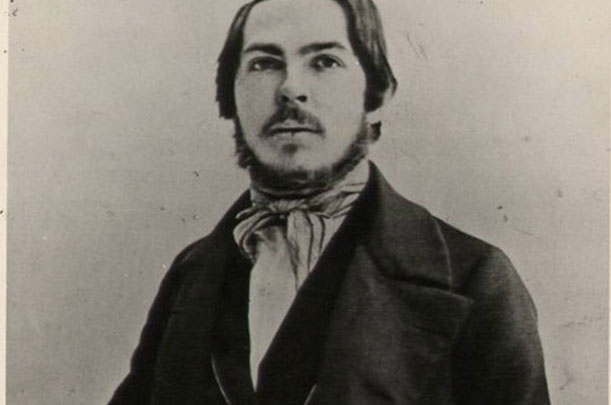

Engels had been sent to Manchester to take up a middle-management position in a mill, Ermen & Engels, that manufactured patent cotton thread. The work was tedious and clerical, and Engels soon realized that he was less than welcome in the company. The senior partner, Peter Ermen, viewed the young man as little more than his father’s spy and made it clear that he would not tolerate interference in the running of the factory. That Engels nonetheless devoted the best years of his life to what he grimly called “the bitch business,” grinding through reams of stultifying correspondence for the better part of 20 years, suggests not so much obedience to his father’s wishes as a pressing need to earn a living. As part-owner of the mill, he eventually received a 7.5 percent share in Ermen & Engels’ rising profits, earning £263 in 1855 and as much as £1,080 in 1859—the latter a sum worth around $168,000 today.

Peter Ermen, the Engels family’s business partner in Manchester, was a taskmaster who tolerated little independence in his managers.

What made Engels different from the mill owners with whom he mixed was how he spent his wealth (and the contents of Peter Ermen’s petty-cash box, which was regularly pilfered). Much of the money, and almost all of Engels’ spare time, was devoted to radical activities. The young German fought briefly in the revolutions of 1848-9, and for decades pursued an intensive program of reading, writing and research that resulted in a breakdown as early as 1857 but eventually yielded a dozen major works. He also offered financial support to a number of less-well-off revolutionaries—most important, Karl Marx, whom he had met while traveling to Manchester in 1842. Even before he became relatively wealthy, Engels frequently sent Marx as much as £50 a year—equivalent to around $7,500 now, and about a third of the annual allowance he received from his parents.

Few of Engels’ contemporaries knew of this hidden life; fewer still were aware of Mary Burns. As a result, almost all of what we know of Burns’ character comes from Engels’ surviving correspondence and a handful of clues exhumed from local archives.

It is not even certain where they met. Given what we know of working-class life during this period, it seems likely that Mary first went to work around age 9, and that her first job would have been as a “scavenger,” one of the myriad of nimble children paid a few pennies a day to keep flying scraps of fluff and cotton out of whirring factory machinery. The noted critic Edmund Wilson took this speculation further, writing that by 1843 Mary had found a job in Ermen’s mill. But Wilson gave no source for this assertion, and other biographers argue that Engels’ less-than-gallant pen portrait of his female employees—”short, dumpy and badly formed, decidedly ugly in the whole development of the figure”—makes it unlikely that he met the “very good natured and witty” young woman whom Marx remembered on the factory floor.

The Manchester slums of the mid-19th century were the subject of Engels’ first book, and a district that—thanks to his lover Mary Burns—he came to know remarkably well.

If Mary was not a factory girl, there were not too many other ways in which she could have made a living. She lacked the education to teach, and the only other respectable employment available was probably domestic service; an 1841 census does suggest that she and her younger sister, Lizzie, worked as servants for a while. A ”Mary Burn” of the right age and “born in this parish” is recorded in the household of a master painter named George Chadfield, and it may be, as Belinda Webb suggests, that Burns took this job because it offered accommodation. Her mother had died in 1835, and she and her sister had to come to terms with a stepmother when their father remarried a year later; perhaps there were pressing reasons for their leaving home. Certainly a career in domestic service would have taught Mary and Lizzie the skills they needed to keep house for Engels, which they did for many years beginning in 1843.

Not every historian of the period believes that Mary was in service, though. Webb, noting that Engels described taking frequent, lengthy walking tours of the city, argues that Mary would scarcely have had the time to act as his guide to Manchester had she labored as a factory hand or servant, and may instead have been a prostitute. Webb notes that Burns was said to have sold oranges at Manchester’s Hall of Science–and “orange selling” had long been a euphemism for involvement in the sex trade. Nell Gwyn, King Charles II’s “Protestant Whore,” famously hawked fruit at Drury Lane Theater, and the radical poet Georg Weerth–whom Mary knew, and who was one of Engels’ closest associates—penned some double entendre-laced lines in which he described a dark-eyed Irish strumpet named Mary who sold her “juicy fruits” to “bearded acquaintances” at the Liverpool docks.

That Engels’ relationship with Mary had a sexual element may be guessed from what what might be a lewd phrase of Marx’s; taking in the news that Engels had acquired an interest in physiology, the philosopher inquired: “Are you studying…on Mary?” Engels did not believe in marriage—and his correspondence reveals a good number of affairs—but he and Burns remained a couple for almost 20 years.

Nothing is known for certain about Mary’s involvement in Engels’ political life, but a good deal can be guessed. Edmund and Ruth Frow point out that Engels describes the Manchester slum district known as Little Ireland in such graphic detail that he must have known it; Mary, they argue, “as an Irish girl with an extended family…would have been able to take him around the slums…. If he had been on his own, a middle-class foreigner, it is doubtful he would have emerged alive, and certainly not clothed.”

The interior of an Irish hovel during the great famine of 1845-50. Engels toured Ireland with Mary Burns in 1856, when almost every village still suffered from the consequences of the disaster.

Engels’ acquaintance with Manchester’s worst slums is a matter of some significance. Though he had been born in a business district in the Ruhr, and though (as his biographer Gustav Meyer puts it) he “knew from childhood the real nature of the factory system”—Engels was still shocked at the filth and overcrowding he found in Manchester. “I had never seen so ill-built a city,” he observed. Disease, poverty, inequality of wealth, an absence of education and hope all combined to render life in the city all but insupportable for many. As for the factory owners, Engels wrote, “I have never seen a class so demoralized, so incurably debased by selfishness, so corroded within, so incapable of progress.” Once, Engels wrote, he went into the city with such a man “and spoke to him of the bad, unwholesome method of building, the frightful condition of the working people’s quarters.” The man heard him out quietly “and said at the corner where we parted: ‘And yet there is a great deal of money to be made here: good morning, sir.’ “

Making the acquaintance of the Burns sisters also exposed Engels to some of the more discreditable aspects of the British imperialism of the period. Although born in England, Mary’s parents had been immigrants from Tipperary, in the south of Ireland. Her father, Michael, labored on and off as a cloth dyer, but ended his days in miserable poverty, spending the last 10 years of his life in a workhouse of the sort made notorious in Oliver Twist. This, combined with the scandal of the Great Famine that gripped Ireland between 1845 and 1850, and saw a million or more Irish men, women and children starve to death in the heart of the world’s wealthiest empire, confirmed the Burns sisters as fervent nationalists. Mary joined Engels on a brief tour of Ireland in 1856, during which they saw as much as two-thirds of the devastated country. Lizzie was said to have been even more radical; according to Marx’s son-in-law, Paul Lafargue, she offered shelter to two senior members of the revolutionary Irish Republican Brotherhood who were freed from police custody in 1867 in a daring operation mounted by three young Fenians known as the Manchester Martyrs.

Three young Fenians free two senior Irish revolutionaries from a Manchester police van in November 1867. They were captured and hanged, but the freed men—Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy—escaped to the United States. Some sources say Lizzie Burns helped spirit the pair out of Manchester.

Thanks to Manchester’s census records and rates books from this period—and to the painstaking work of local labor historians—it is possible to trace the movements of Engels and the Burns sisters under a variety of pseudonyms. Engels passed himself off as Frederick Boardman, Frederick Mann Burns and Frederick George Mann, and gave his occupation as bookkeeper or “commercial traveler.” There are gaps in the record–and gaps in Engels’ commitment to both Manchester and Mary; he was absent from England from 1844 until the very end of 1849. But Burns evidently retained her place in Engels’ affections through the revolutionary years of 1848-9. Webb notes that, after his return to Manchester, “he and Mary seem to have proceeded more formally,” setting up home together in a modest suburb. Lizzie moved in and seems to have acted as housekeeper, though details of the group’s living arrangements are very hard to come by; Engels ordered that almost all of the personal letters he wrote during this period be destroyed after his death.

Engels seems to have acknowledged Mary, at least to close acquaintances, as more than a friend or lover. “Love to Mrs Engels,” the Chartist Julian Harney wrote in 1846. Engels himself told Marx that only his need to maintain his position among his peers prevented him from being far more open: “I live nearly all the time with Mary so as to save money. Unfortunately I cannot manage without [private] lodgings; if I could I would live with her all the time.”

Engels and Mary moved frequently. There were lodgings in Burlington and Cecil Streets (where the Burns sisters appear to have earned extra money by renting out spare rooms), and in 1862 the couple and Lizzie moved into a newly built property in Hyde Road (the street on which the Manchester Martyrs would free Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy five years later). But the years–and perhaps Engels’ long absences on business, private and revolutionary—began to take their toll. In her 20s, Eleanor Marx recorded, Mary “had been pretty, witty and charming…but in later years [she] drank to excess.” This may be no more than family lore—Eleanor was only 8 when Burns died, and she admitted in another letter that “Mary I did not know”—but it seems to fit the known facts well enough. When Burns died, on January 6, 1863, she was only 40.

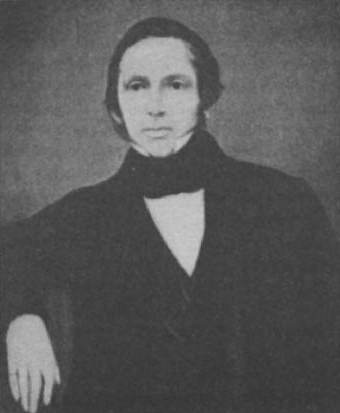

Jenny Marx—neé Jenny von Westphalen, a member of Prussia’s aristocracy—in 1844.

If it is Mary Burns’ death, not life, that scholars focus on, that is because it occasioned a momentous falling-out between Engels and Marx—the only one recorded in four decades of close friendship. The earliest signs of discord date back several years. During a sojourn in Belgium between 1845 and 1848, during which the two men wrote the Communist Manifesto, Mary went to live in Brussels, an unusual adventure in those days for someone of her sex and class. Jenny Marx had few acquaintances among working-class women, and was undoubtedly shocked when Engels held up his lover as a model for the woman of the future. Burns, Jenny thought, was “very arrogant,” and she observed, sarcastically, that “I myself, when confronted with this abstract model, appear truly repulsive in my own eyes.” When the two found themselves together at a workers’ meeting, Simon Buttermilch reported, Marx “indicated by a significant gesture and a smile that his wife would in no circumstances meet Engels’ companion.”

It was against this backdrop that Engels wrote to Marx to tell his friend of Mary’s death. “Last night she went to bed early,” he wrote, “and when at midnight Lizzie went upstairs, she had already died. Quite suddenly. Heart disease or stroke. I received the news this morning, on Monday evening she was still quite well. I can’t tell you how I feel. The poor girl loved me with all her heart.”

Marx sympathized–briefly. “It is extraordinarily difficult for you,” he wrote, “who had a home with Mary, free and withdrawn from all human muck, as often as you pleased.” But the remainder of the missive was devoted to a long account of Marx’s woes, ending with a plea for money. “All my friends,” Engels fired back in anger, “including philistine acquaintances, have shown me, at this moment which hit me deeply, more sympathy and friendship than I expected. You found this moment appropriate to display the superiority of your cool intellect.”

Engels in later life. He died in 1895, at age 74.

Marx wrote again, apologizing, extending more elaborate condolences and blaming his first letter on his wife’s demands for money. “What drove me particularly mad,” he wrote, “was that [Jenny] thought I did not report to you adequately our true situation.” Mike Gane, among other writers, suspects that Marx objected to Engels’ love of a working-class woman not on the grounds of class, but because the relationship was bourgeois, and hence violated the principles of communism. Whatever the reason for the argument, Engels seems to have been glad when it ended.

He lived with Mary’s sister for 15 more years. Whether their relationship was as passionate as the one Engels had enjoyed with Mary may be doubted, but he was certainly very fond of Lizzie Burns; just before she was struck down by some sort of tumor in 1878, he acceded to her dying wish and married her. “She was of genuine Irish proletarian stock,” he wrote, “and her passionate and innate feelings for her class were of far greater value to me and stood me in better stead at moments of crisis than all the refinement and culture of your educated and ascetic young ladies.”

Historians remain divided over the importance of Engels’ relations with the Burns sisters. Several biographers have seen Mary and Lizzie as little more than sexual partners who also kept house, something that a Victorian gentleman could scarcely have been expected to do for himself. Terrell Carver has suggested that “in love, Engels does not seem to have gone in search of his intellectual equal.”

Others see Mary Burns as vastly more important. ”I wanted to see you in your own homes,” Engels wrote in dedicating his first book to “the Working Classes of Great Britain.” “To observe you in everyday life, to chat with you on your conditions and grievances, to witness your struggles.” He never could have achieved this ambition without a guide, certainly not in the short span of his first sojourn in England. And achieving it marked him for life. “Twenty months in Manchester and London,” W.O. Henderson observes–for which read 10 or 15 months with Mary Burns—”had turned Engels from an inexperienced youth into a young man who had found a purpose in life.”

Sources

Roland Boer. “Engels’ contradictions: a reply to Tristram Hunt.” International Socialism 133 (2012); William Delaney. Revolutionary Republicanism and Socialism in Irish History, 1848-1923. Lincoln [NE]: Writer’s Showcase, 2001; Edmund and Ruth Frow. Frederick Engels in Manchester and “The Condition of the Working Class in England”; Salford: Working Class Movement Library, 1995; Mike Gane. Harmless Lovers? Gender, Theory and Personal Relationship. London: Routledge, 1993; Lindsay German. Frederick Engels: life of a revolutionary. International Socialism Journal 65 (1994); W.O. Henderson. The Life of Friedrich Engels. London: Frank Cass, 1976; W.O. Henderson. Marx and Engels and the English Workers, and Other Essays. London: Frank Cass, 1989; Tristram Hunt. The Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels. The Life and Times of the Original Champagne Socialist. London: Penguin, 2010; Sarah Irving. “Frederick Engels and Mary and Lizzie Burns.” Manchester Radical History, accessed April 3, 2013; Mick Jenkins. Frederick Engels in Manchester. Manchester: Lancashire & Cheshire Communist Party, 1964; Jenny Marx to Karl Marx, March 24, 1846, in Marx/Engels Collected Works, 38. New York: International Publishers, 1975; Marx to Engels, January 8, 1863; Engels to Marx, January 13, 1863; Marx to Engels, January 24, 1863; Engels to Marx, January 26, 1863, all in Marx/Engels Collected Works, 41. New York: International Publishers, 1985; Belinda Webb. Mary Burns. Unpublished Kingston University PhD thesis, 2012; Roy Whitfield. Frederick Engels in Manchester: The Search for a Shadow. Salford: Working Class Movement Library, 1988.