Protest in Belarus: Who? Why? With what aims? — a politico-economic analysis

By Aleksandr Vladimirovich Buzgalin

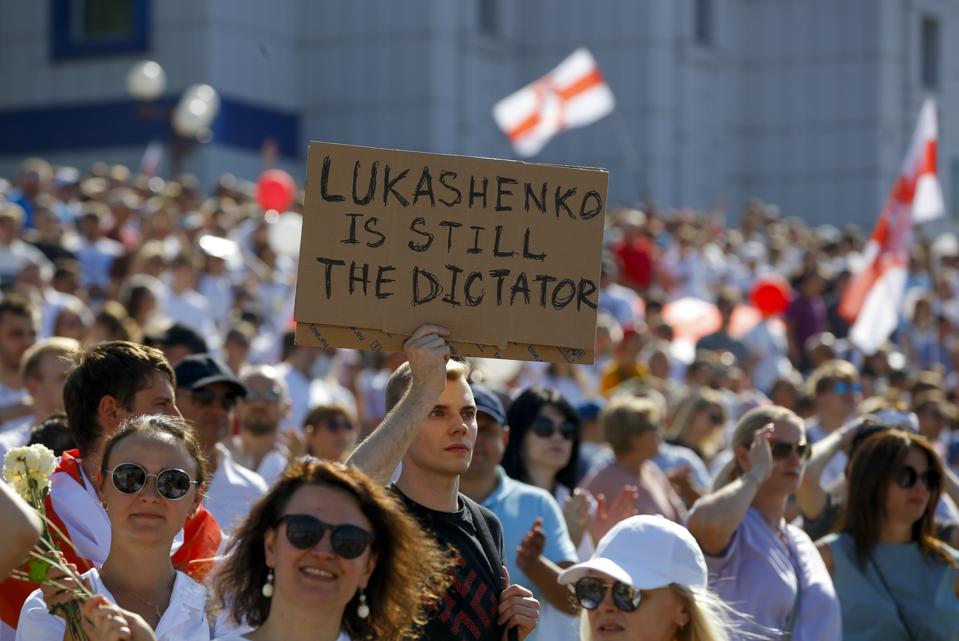

August 27, 2020 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal — The wave of debate that has followed the events in Belarus has left out of the account the key questions: why are people taking to the streets of Minsk and other cities, and just who are these people? What exactly do they want, that they are prepared to risk their freedom, their health and even their lives? Why are there many tens of thousands of them, probably more? And why is this happening in Belarus, to all appearances an unusually peaceful and stable country, with strong historical traditions of antifascism and of friendship with Russia?

Before suggesting answers to these questions, let me stress: I am not writing these lines as a mere onlooker. My homeland was and remains the USSR, of which Belarus is an inseparable part. These are the lines of someone who has many comrades in Minsk, and to whom the fate of Belarus is not a matter of personal indifference.

Now to the essence.

Belarusian capitalism

At the heart of the country’s present-day problems are the peculiarities of its socio-economic and political system. The last few decades have seen the formation in Belarus of an entirely distinctive model of semi-peripheral capitalism — of a system in which economic and political power does not, fundamentally, lie with private capital but with a bureaucratic-paternalist state apparatus, whose symbol (though not its owner) is Lukashenko.

Unlike the situation in the Russian Federation and most other countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, large-scale oligarchic capital is only weakly developed in Belarus, and its relationship to the state apparatus is for the most part a subordinate one. Accordingly, the elements of private capital that are not intertwined with the bureaucracy submit to the functionaries and pay tribute to them. It is important to note that this subordination is not just economic in nature, but also administrative, political and even cultural-ideological. This applies to small, middle and large businesses alike (the situation in Russia is similar, but here the capital-owning class taken together dominates the state, while in Belarus the reverse is true).

It is significant that in Belarus the state is at once paternalist and bureaucratic-capitalist. In the first of these roles it devotes a substantial part of its resources to maintaining industry, the rural sector, infrastructure and the population. In its second role the bureaucracy, intermingled with capital, subjugates and exploits the majority of working people in both economic and administrative-political fashion, acting as a state capitalist.

The worker majority

The key point here is that in Belarus, working people (I employ this concept, now so little used, quite deliberately), who not so long ago lived relatively prosperous and secure lives on the whole, have been deprived of the chance to be human beings instead of mere cogs in a machine, parts of a depersonalised, obedient mass. They have been robbed of the opportunity to be individuals, subjects of economic, political and cultural life, instead of passively obedient objects of the ministrations (with inverted commas, and without) of “Daddy” Lukashenko.

It is also true that the “prosperity” of most Belarusian workers in recent times has become altogether relative: economic and social development has slowed, while social inequality has increased.

The result has been a hidden readiness on the part of most ordinary Belarusians to support the protests. But at the same time, there is also a fear of losing the relative stability of their paternalistically guaranteed existence. Hence the position that until recently most of the country’s rank and file workers implicitly embraced: for change, but not for liberal capitalism, and thus if there was no alternative, then better that Lukashenko should stay.

In the course of the protests, however, Lukashenko’s exclusive reliance on force has altered the situation not just by the day, but by the hour. “Ordinary” citizens have been waking up, and coming to realise that paternalism implies not just stability, but also stagnation. Meanwhile capitalism, even of the paternalist-bureaucratic variety, involves exploitation and subjection…

The opposition: who and why

The fundamentally capitalist nature of Belarusian society fosters an orientation in the majority of the population, especially the youth (and still more, the “elite” youth), toward the liberal-consumerist system of values that dominates the world in the twenty-first century.

(As an important digression, I would note that this system of values is often, mistakenly, described as “Western”. But it is not Western; it is a world-wide system of interests and values that is shaped by global capital, even though its roots lie in the West and it has acquired a “residence permit” in the East).

Prime place in this system of values is held by self-enrichment, which is directly associated with the consumption of prestige brands, with being “part of the trend”, and with individualism — that is, with everything that forms the basis of the ideology and psychology of neoliberalism. In paternalist-capitalist Belarus these goals of young people are on the one hand cultivated (by capitalism) and on the other hand are blocked (by bureaucratic paternalism). The result is a contradiction that has led to an explosion. Allied to this is the position of a significant section of the middle and petty bourgeoisie, as well as of freelance professionals and of all those who consider themselves (falsely, for the most part!) to be the owners of a substantial “human capital”. The latter cast of mind is especially characteristic of young people from the large cities who have received a Western-style education.

(I shall permit myself another important digression: in Lukashenko’s Belarus, the basically capitalist education system has always taught young people in accordance with United State precepts, whether in economics, management, philosophy or political science).

Further, I would note the lack of any opportunity for self-expression or for criticism of the existing system.

All this is in the context of an objectively inevitable economic, informational and cultural intermingling with global politico-economic capital (“the West”).

As a consequence the social strata listed above, that comprise the so-called “middle class” in large cities (in reality, these are the uppermost 15 to 20 per cent of the population), have come in their majority to represent the opposition to the Lukashenko system. These people are far from being a majority overall, but they are active in political and informational terms.

Here we encounter another factor: the bureaucracy, remote from the actual lives, interests and problems of the people and of the country as a whole, and not subject to control by the citizens, has inevitably “grown stupid”, losing out to the opposition intellectually as well. The result is that the protesters in most cases are also winning the information and communications war over the authorities. To this, the latter have responded with increasing levels of brute force, which simply multiplies the number of their opponents…

The external factor

Finally, we must also take account of the external factor. Belarus is bordered to the north and west by member countries of the EU (with the US standing behind them), to the south by Ukraine, and to the east by Russia (and China, in the political if not geographical sense). In its struggle for Belarus as an economic, political and military bridgehead, the “West” acts forcefully; against ordinary Belarusians, especially younger ones, it deploys not just money and sophisticated political techniques, but most important, modern methods of cultural, ideological and informational manipulation. The “East” is losing, acting weakly and employing outmoded methods. It is attempting to solve the problems it confronts exclusively on the plane of personal relationships between leaders, of economic deals and of operations by secret police services.

The sum of all this provides an answer to the question of which people are joining the protests, and why.

The barricades of protest

The source of today’s protests is the objective rejection of the existing Belarusian economic and political system by the majority of the so-called “middle class”, which with informational and organisational support from the “West” has gradually reached the point of open struggle. Adding to the readiness of this stratum to come into the streets have been additional factors, nurtured especially to serve this end — nationalist sentiment, money, provocations, and the work of political and other specialists. The broth of protest has come to the boil.

Who is now standing on the other side of the barricades?

Obviously, the state apparatus and its machine of coercion.

And what about the majority of workers?

For the present (this text was written on 12 August), most of them are remaining on the sidelines, declining to take part directly in the protests, as they sense half-consciously that for the working people of Belarus, a victory for the neoliberal opposition would turn into a worse evil than if the existing system were to prevail. Let me explain: the workers, peasants, teachers and medical personnel of Belarus will not win political freedom as a gift from the neoliberal system. At best, they will be granted formal concessions that conceal the total manipulation of public opinion by global corporate capital and its political representatives. At worst, they will finish up beneath the dictatorship of nationalists with pro-fascist inclinations. Economically, the worker majority (including the naïve young protesters) will not receive anything from neoliberalism except the curtailing of already scant social benefits, and the opportunity to transform themselves from a paternalistically defended proletariat (though one without political rights) into an impoverished, politically unorganised precariat, that serves as a perfect nutrient medium for nationalism and dictatorship.

But that’s for the present. If the system of repression grows and becomes self-perpetuating (and this tendency is innate in a repressive state system that is not under the control of citizens), the wave of protests will come to include “ordinary” Belarusians. Like it or not, they will come to understand that the existing regime is prepared to direct reprisals against everyone without distinction, and that tolerating it is impossible.

At that point the majority of the Belarusian people, who for all their patience are fearless when enraged, will start rising up in earnest…

Postscript

“Belarus, our own dear land…” — the words are from an old song — is a part of our past, but not only of our past. It is a part of fate, of a fate at whose heart lies not just the victory in the great war against fascism, but also creative activity. Moreover, this is creative activity carried on even under the most monstrous conditions, and on the basis of people’s own initiative and self-organisation. An example is the partisan movement. It was precisely here that Belarus showed an example for everyone of how a people can struggle against an enemy. It was not by chance that it was in Minsk, on the very streets and squares where today the clashes are taking place, that the first parade of the Great Patriotic War took place — a demonstration and parade by thirty partisan brigades, lasting for several hours on 16 July, 1944. On the following day 57,000 captured German officers and troops were led through the streets of Moscow, and the asphalt was washed after they had passed…

Aleksandr Vladimirovich Buzgalin is Doctor of Economic Sciences, Professor, Moscow Financial-Juridical University (MFYuA). He can be contacted at buzgalin@mail.ru. Translation by Renfrey Clarke