The planning and politics of conversion: World War II lessons for a Green New Deal — Part 1

By Marty Hart-Landsberg

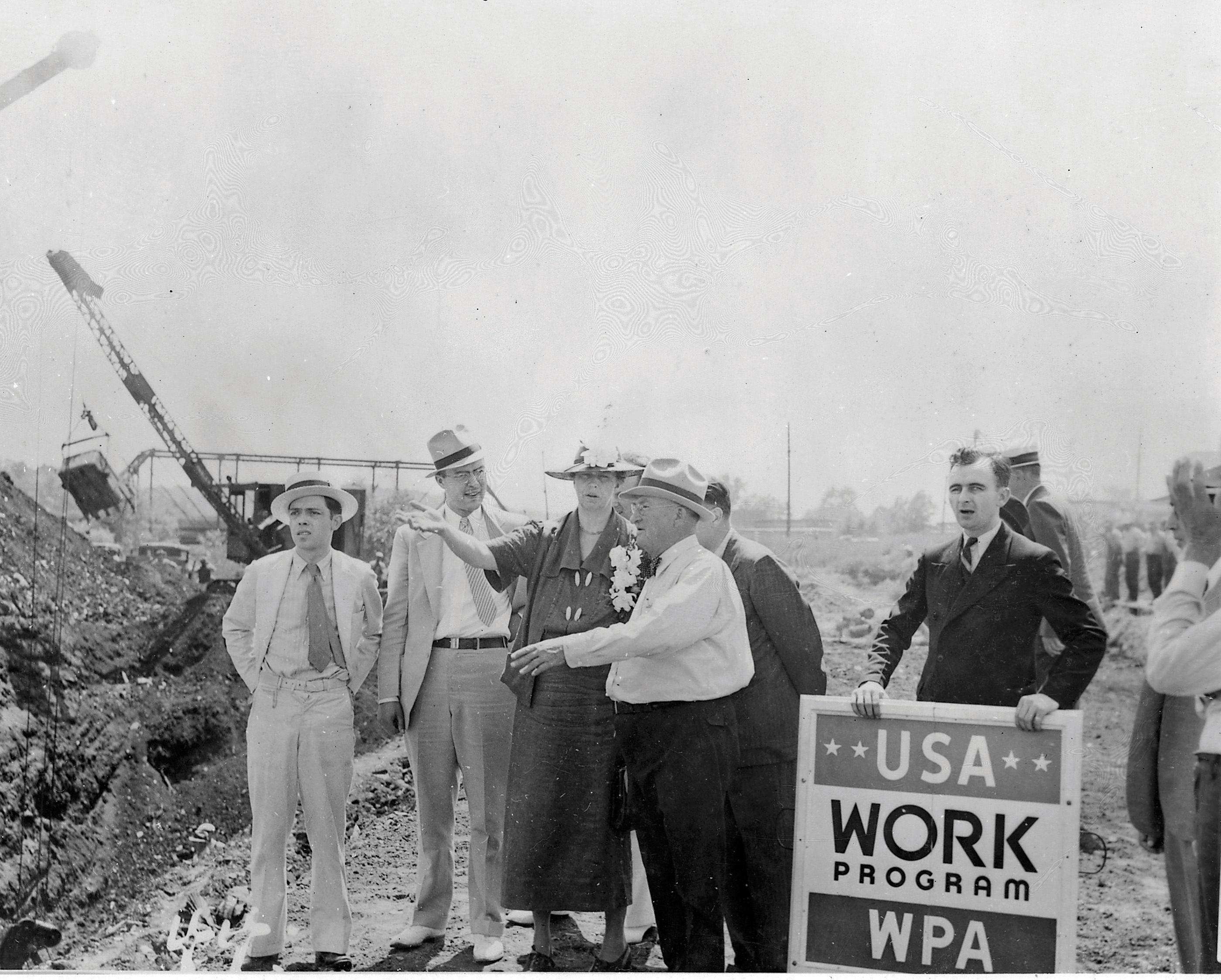

December 11, 2020 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from Reports from the Economic Front — This is the first in a series of posts that aim to describe and evaluate the World War II mobilization experience in the United States in order to illuminate some of the economic and political challenges we can expect to face as we work for a Green New Deal.

This post highlights the successful government directed wartime reorientation of the U.S. economy from civilian to military production, an achievement that both demonstrates the feasibility of a rapid Green New Deal transformation of the U.S. economy and points to the kinds of organizational capacities we will need to develop. The post also highlights some of the strategies employed by big business to successfully stamp the wartime transformation as a victory for “market freedom,” an outcome that strengthened capital’s ability to dominate the postwar U.S. political economy and suggests the kind of political struggles we can expect and will need to overcome as we work to achieve a just Green New Deal transformation.

The climate challenge and the Green New Deal

We are hurtling towards a climate catastrophe. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, warns that we must limit the increase in the global mean temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100 if we hope to avoid a future with ever worsening climate disasters and “global scale degradation and loss of ecosystems and biodiversity.” And, it concludes, to achieve that goal global net carbon dioxide emissions must fall by 45 per cent by 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Tragically, none of the major carbon dioxide emitting nations has been willing to pursue the system-wide changes necessary to halt the rise in the global mean temperature. Rather than falling, carbon dioxide emissions rose over the decade ending in 2019. Only a major crisis, in the current case a pandemic, appears able to reverse the rise in emissions.

Early estimates are that the COVID-19 pandemic will cause a fall in global emissions of somewhere between 4 and 7 percent in 2020. But the decline will likely be temporary. For example, the International Monetary Fund is forecasting an emission rise of 5.8 percent in 2021. This bounce back is in line with what happened after the 2008-09 Great Recession. After falling by 1.4 percent in 2009, global emissions grew by 5.1 percent in 2010.

Motivated by signs of the emerging climate crisis—extreme weather conditions, droughts, floods, warming oceans, rising sea levels, fires, ocean acidification, and soil deterioration—activists in the United States have worked to build a movement that joins climate and social justice activists around a call for a Green New Deal to tackle both global warming and the country’s worsening economic and social problems. The Green Party has promoted its ecosocialist Green New Deal since 2006, but it was the 2018 mass actions by new climate action groups such as Extreme Rebellion and the Sunrise Movement and then the 2019 introduction of a Green New Deal congressional resolution by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Edward Markey that helped popularize the idea.

The Ocasio-Cortez—Markey resolution, echoing the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, calls for a ten-year national program of mobilization designed to cut CO2 emissions by 40-60 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Its program includes policies that aim at replacing fossil fuels with clean, renewable sources of energy, and existing forms of transportation, agriculture, and urban development with new affordable and sustainable ones; encouraging investment and the growth of clean manufacturing; and promoting good, high paying union jobs and universal access to clean air and water, health care, and healthy food.

While there are similarities, there are also important differences, between the Green Party’s Green New Deal and Ocasio-Cortez—Markey’s Green New Deal, including over the speed of change, the role of public ownership, and the use of fracking and nuclear power for energy generation. More generally, there are also differences among supporters of a Green New Deal style transformation over whether the needed government investments and proposed social policies should be financed by raising taxes, slashing the military budget, borrowing, or money creation. There are also environmentalists who oppose the notion of sustained but sustainable growth explicitly embraced by many Green New Deal supporters and argue instead for a policy of degrowth, or a “Green New Deal without growth.”

These arguments are important, representing different political sensibilities and visions, and need to be taken seriously. But what has largely escaped discussion is any detailed consideration of the actual process of economic transformation required by any serious Green New Deal program. Here are some examples of the kind of issues we will need to confront:

Fossil fuel production has to be ratcheted down, which will dramatically raise fossil fuel prices. The higher cost of fossil fuels will significantly raise the cost of business for many industries, especially air travel, tourism, and the aerospace and automobile industries, triggering significant declines in demand for their respective goods and services and reductions in their output and employment. We will need to develop a mechanism that will allow us to humanely and efficiently repurpose newly created surplus facilities and provide alternative employment for released workers.

New industries, especially those involved in the production of renewable energy will have to be rapidly developed. We will need to develop agencies capable of deciding the speed of their expansion as well as who will own the new facilities, how they will be financed, and how best to ensure that the materials required by these industries will be produced in sufficient quantities and made available at the appropriate time. We will also have to develop mechanisms for deciding where the new industries will be located and how to develop the necessary social infrastructure to house and care for the new workforce.

The list goes on—we will need to ensure the rapid and smooth expansion of facilities capable of producing electric cars, mass transit vehicles, and a revitalized national rail system. We will need to organize the retrofitting of existing buildings, both office and residential, as well as the training of workers and the production of required equipment and materials. The development of a new universal health care system will also require the planning and construction of new clinics and the development of new technologies and health practices.

The challenges sound overwhelming, especially given the required short time frame for change. But, reassuringly, the U.S. government faced remarkable similar challenges during the war years when, in approximately three years, it successfully converted the U.S. economy from civilian to military production. This experience points to the importance of studying the World War II planning process for lessons and should give us confidence that we can successfully carry out our own Green New Deal conversion in a timely fashion.

World War II economic mobilization

The name Green New Deal calls to mind the New Deal of the 1930s, which is best understood as a collection of largely unrelated initiatives designed to promote employment and boost a depressed economy. In contrast, the Green New Deal aims at an integrated transformation of a “functioning” economy, which is a task much closer to the World War II transformation of the U.S. economy. That transformation required the repression of civilian production, much like the Green New Deal will require repression of the fossil fuel industry and those industries dependent on it. Simultaneously, it also required the rapid expansion of military production, including the creation of entirely new products like synthetic rubber and weapon systems, much like the Green New Deal will require expansion of new forms of renewable energy, transportation, and social programs. And it also required the process of conversion to take place quickly, much like what is required under the Green New Deal.

J.W. Mason and Andrew Bossie highlight the contemporary relevance of the wartime experience by pointing out:

Just as in today’s public-health and climate crises, the goal of wartime economic management was not to raise GDP in the abstract, but to drastically raise production of specific kinds of goods, many of which had hardly figured in the prewar economy. Then as now, this rapid reorganization of the economy required a massive expansion of public spending, on a scale that had hardly been contemplated before the emergency. And then as, potentially, now, this massive expansion of public spending, while aimed at the immediate non-economic goal, had a decisive impact on long-standing economic problems of stagnation and inequality. Of course, there are many important differences between the two periods. But the similarities are sufficient to make it worth looking to the 1940s for economic lessons for today.

Before studying the organization, practice, and evolution of the World War II era planning system, it is useful to have an overall picture of the extent, speed, and success of the economy’s transformation. The following two charts highlight the dominant role played by the government. The first shows the dramatic growth and reorientation in government spending beginning in 1941. As we can see federal government war expenditures soared, while non-war expenditures actually fell in value. Military spending as a share of GNP rose from 2.2 percent in 1940, to 11 percent in 1941, and to 31.2 percent in 1942.

The second shows that the expansion in plant and equipment required to produce the goods and services needed to fight the war was largely financed by the government. Private investment actually fell in value over the war years.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Budget, The United States at War, Development and Administration of the War Program by the Federal Government, Washington DC: The U.S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p. 92.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Budget, The United States at War, Development and Administration of the War Program by the Federal Government, Washington DC: The U.S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p. 115.

The next chart illustrates the speed and extent of the reorientation of industrial production over the period 1941-1944. As we can see, while industrial production aimed at military needs soared, non-military industrial production significantly declined.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Budget, The United States at War, Development and Administration of the War Program by the Federal Government, Washington DC: The U.S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p. 104.

The next two charts illustrate the success of the conversion process. The first shows the rapid increase in the production of a variety of military weapons and equipment. The second demonstrates why the United States was called the “Arsenal of democracy”; it produced the majority of all the munitions produced during World War II.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Budget, The United States at War, Development and Administration of the War Program by the Federal Government, Washington DC: The U.S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p. 319

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Budget, The United States at War, Development and Administration of the War Program by the Federal Government, Washington DC: The U.S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p. 507.

Significantly, while the rapid growth in military related production did boost the overall growth of the economy, because it was largely achieved at the expense of nonmilitary production, the economy’s overall growth over the years 1941-44/45, was far from extraordinary. For example, the table below compares the growth in real gross nonfarm product over the early years of the 1920’s to that of the early years of the 1940’s. As we can see, there is little difference between the two periods, and that holds true even if we exclude the last year of the war, when military spending plateaued and military production began to decline. The same holds true when comparing just the growth in industrial production over the two periods.

Years Growth in real gross nonfarm product

| 1921-25 | 28.4% |

| 1941-45 | 24.6% |

| 1921-24 | 26.2% |

| 1941-44 | 25.8% |

Source: Harold G. Vatter, The U.S. Economy in World War II, New York: Columbia University Press, 1985, p. 22.

This similarity between the two periods reinforces the point that the economic success of the war years, the rapid ramping up of military production, was primarily due to the ability of government mobilization agencies to direct an economic conversion that privileged the production of goods and services for the military at the expense of non-military goods and services. This experience certainly lends credibility to those who seek a similar system-wide conversion to achieve a Green New Deal transformation of the U.S. economy.

Such a transformation is not without sacrifice. For example, workers did pay a cost for the resulting suppression of civilian oriented production, but it was limited. As Harold Vatter points out: “There were large and real absolute decreases in total consumer expenditures between 1941 and 1945 on some items considered important in ordinary times. Prominent among these, in the durable goods category, were major home appliances, new cars, and net purchases of used cars, furniture, and radio and TV sets.”

At the same time there were real gains for workers. Overall personal consumption which rose in both 1940 and 1941, declined absolutely in 1942, but then began a slow and steady increase, with total personal consumption higher in 1945 than in 1941. However, this record understates the real gains. The U.S. civilian population declined from 131.6 million in 1941 to 126.7 million in 1944. Thus, the gain in personal consumption on a per capita basis was significant. As Vatter notes, “real employee compensation per private employee in nonfarm establishments rose steadily ever year, and in 1945 was over one-fifth above the 1941 level. . . . More broadly, similar results show up for the index of real disposable personal income per capita, which increased well over one-fourth during the same war years.” Of course, these gains were largely the result of more people working and for longer hours; it was definitely earned. Also important is the fact that pretax family income rose faster for those at the bottom of the income distribution than for those at the top, helping to reduce overall income inequality.

In sum, there are good reasons for those seeking to implement a Green New Deal style transformation of the U.S. economy to use the World War II planning experience as a template. A careful study of that experience can alert us to the kinds of organizational and institutional capacities we will need to develop. And, it is important to add, it can also alert us to the kinds of political challenges we can expect to face.

Planning and politics

The success of the U.S. economy’s World War II transformation was due, in large part, to the work of a series of changing and overlapping mobilization agencies that President Roosevelt established by executive order and then replaced or modified as new political and economic challenges emerged. Roosevelt took his first meaningful action to help prepare the United States economy for war in May 1940, when he reactivated the World War 1-era National Defense Advisory Commission (NDAC). The NDAC was replaced by the Office of Production Management (OPM) in December 1940. The Supply Priorities and Allocation Board (SPAB) was then created in August 1941 to develop a needed longer-term planning orientation to guide the work of the OPM. And finally, both the OPM and the SPAB were replaced by the War Production Board (WPB) in January 1942. With each change, decision-making became more centralized, planning responsibilities expanded, and authority to direct economic activity strengthened.

The work of these agencies was greatly enhanced by a number of other initiatives, one of the most important being the August 1940 establishment of the Defense Plant Corporation (DPC). The DPC was authorized to directly finance and own plant and equipment vital to the national defense. The DPC ended up financing and owning roughly one-third of the plant and equipment built during the war, most of which was leased to private companies to operate for a minimal amount, often $1 a year. The aircraft industry was the main beneficiary of DPC investment, but plants were also built to produce synthetic rubber, ships, machine tools, iron and steel, magnesium, and aluminum.

Despite its successful outcome, the process of economic conversion was far from smooth and the main reason was resistance by capitalists. Still distrustful of New Deal reformers, most business leaders were critical of any serious attempt at prewar planning that involved strengthening government regulation and oversight of their respective activities. Rather, they preferred to continue their existing practice of individually negotiating contracts with Army and Navy procurement agencies. Many also opposed prewar government entreaties to expand their scale of operations to meet the military’s growing demand for munitions and equipment. Their reasons were many: they were reluctant to expand capacity after a decade of depression; civilian markets were growing rapidly and highly profitable; and the course of the war, and the U.S. participation in it, remained uncertain.

Their attitude and power greatly influenced the operation and policies of the NDAC, which was built on industry divisions run by industry leaders, most of whom were so-called “dollar-a-year men” who continued to draw their full salaries from the corporations that employed them, and advised by industry associations. This business-friendly structure, with various modifications, was then transferred to the OPM and later the WPB.

With business interests well represented in the prewar mobilization agencies, the government struggled to transform the economy in preparation for war. The lack of new business investment in critical industries meant that by mid-1941 material shortages began forcing delays in defense orders; aluminum, magnesium, zinc, steel, and machine tools were all growing scare. At the same time, a number of industries that were major consumers of these scare materials and machinery, such as the automobile industry, also resisted government efforts to get them to abandon their consumer markets and convert to the production of needed military goods.

In some cases, this resistance lasted deep into the war years, with some firms objecting not only to undertaking their own expansion but to any government financed expansion as well, out of fear of post-war overproduction and/or loss of market share. The resulting political tension is captured by the following exchange at a February 1943 Congressional hearing between Senator E. H. Moore of Oklahoma and Interior Secretary and Petroleum Administrator for War Harold L. Ickes over the construction of a petroleum pipeline from Texas to the East Coast:

Secretary Ickes. I would like to say one thing, however. I think there are certain gentlemen in the oil industry who are thinking of the competitive position after the war.

The Chairman. That is what we are afraid of, Mr. Secretary.

Secretary Ickes. That’s all right. I am not doing that kind of thinking.

The Chairman. I know you are not.

Secretary Ickes. I am thinking of how best to win this war with the least possible amount of casualties and in the quickest time.

Senator Moore. Regardless, Mr. Secretary, of what the effect would be after the war? Are you not concerned with that?

Secretary Ickes. Absolutely.

Senator Moore. Are you not concerned with the economic situation with regard to existing conditions after the war?

Secretary Ickes. Terribly. But there won’t be any economic situation to worry about if we don’t win the war.

Senator Moore. We are going to win the war.

Secretary Ickes. We haven’t won it yet.

Senator Moore. Can’t we also, while we are winning the war, look beyond the war to see what the situation will be with reference to –

Secretary Ickes (interposing). That is what the automobile industry tried to do, Senator. It wouldn’t convert because it was more interested in what would happen after the war. That is what the steel industry did, Senator, when it said we didn’t need any more steel capacity, and we are paying the price now. If decisions are left with me, it is only fair to say that I will not take into account any post-war factor—but it can be taken out of my hands if those considerations are paid attention to.

Once the war began, many businesses were also able to build a strategic alliance with the military that allowed them to roll back past worker gains and isolate and weaken unions. For example, by invoking the military’s overriding concern with achieving maximum production of the weapons of war, business leaders were able to defeat union attempts to legislate against the awarding of military contracts to firms in violation of labor law. They also succeeded in ignoring overtime pay requirements when lengthening the workweek and in imposing new workplace rules that strengthened management prerogatives.

If unions struck to demand higher wages or resist unilateral workplace changes, business and military leaders would declare their actions a threat to the wartime effort, which cost them public support. Often the striking unions were threatened with government sanctions by mobilization authorities. In some cases, especially when it came to the aircraft industry, the military actually seized control of plants, sending in troops with fixed bayonets, to break a strike. Eventually, the CIO traded a no-strike pledge for a maintenance of membership agreement, but that often put national union officials in the position of suppressing rank-and-file job actions and disciplining local leaders and activists, an outcome which weakened worker support for the union.

Business didn’t always have its own way. Its importance as essential producer was, during the war, matched by the military’s role as essential demander. And, while the two usually saw eye-to-eye, there were times when military interests diverged from, and dominated, corporate interests. Moreover, as the war continued, government planning agencies gained new powers that enabled them to effectively regulate the activities of both business and the military. Finally, the work of congressional committees engaged in oversight of the planning process as well as pressure from unions and small business associations also helped, depending on the issue, to place limits on corporate prerogatives.

Still, when all was said and done, corporate leaders proved remarkably successful in dominating the mobilization process and strengthening their post-war authority over both the government and organized labor. Perhaps the main reason for their success is that almost from the beginning of the mobilization process, a number of influential business leaders and associations aggressively organized themselves to fight their own two-front war—one that involved boosting production to help the United States defeat the Axis powers and one that involved winning popular identification of the fight for democracy with corporate freedom of action.

In terms of this second front, as J.W. Mason describes:

Already by 1941, government enterprise was, according to a Chamber of Commerce publication, “the ghost that stalks at every business conference.” J. Howard Pew of Sun Oil declared that if the United States abandoned private ownership and “supinely reli[es] on government control and operation, then Hitlerism wins even though Hitler himself be defeated.” Even the largest recipients of military contracts regarded the wartime state with hostility. GM chairman Alfred Sloan—referring to the danger of government enterprises operating after war—wondered if it is “not as essential to win the peace, in an economic sense, as it is to win the war, in a military sense,” while GE’s Philip Reed vowed to “oppose any project or program that will weaken” free enterprise.

Throughout the war, business leaders and associations “flooded the public sphere with descriptions of the mobilization effort in which for-profit companies figured as the heroic engineers of a production ‘miracle’.” For example, Boeing spent nearly a million dollars a year on print advertising in 1943-45, almost as much as it set aside for research and development.

The National Association of Manufactures (NAM) was one of the most active promoters of the idea that it was business, not government, that was winning the war against state totalitarianism. It did so by funding a steady stream of films, books, tours, and speeches. Mark R. Wilson describes one of its initiatives:

One of the NAM’s major public-relations projects for 1942, which built upon its efforts in radio and print media, was its “Production for Victory” tour, designed to show that “industry is making the utmost contributions toward victory.” Starting the first week in May, the NAM paid for twenty newspaper reporters to take a twenty-four-day, fifteen-state trip during which they visited sixty-four major defense plants run by fifty-eight private companies. For most of May, newspapers across the country ran daily articles related to the tour, written by the papers’ own reporters or by one of the wire services. The articles’ headlines included “Army Gets Rubber Thanks to Akron,” “General Motors Plants Turning Out Huge Volume of War Goods,” “Baldwin Ups Tank Output,” and “American Industry Overcomes a Start of 7 Years by Axis.”

It was rarely if ever mentioned by the companies or the reporters that almost all of these new plants were actually financed, built, and owned by the government, or that it was thanks to government planning efforts that these companies had well-trained workers and received needed materials on a timely basis. Perhaps not surprisingly, government and union efforts to challenge the corporate story were never as well funded, sustained, or shaped by as clear a class perspective. As a consequence, they were far less effective.

Paul A.C. Koistinen, in his major study of World War II planning, quotes Hebert Emmerich, past Secretary of the Office of Production Management (OPM), who looking back at the mobilization experience in 1956 commented that “When big business realized it had lost the elections of 1932 and 1936, it tried to come in through the back door, first through the NRA and then through the NDAC and OPM and WPB.” Its success allowed it to emerge from the war politically stronger than when it began.

Capital is clearly much more organized and powerful today than it was in the 1940s. And we can safely assume that business leaders will draw upon all their many strengths in an effort to shape any future conversion process in ways likely to limit its transformative potential. Capital’s wartime strategy points to some of the difficult challenges we must prepare to face, including how to minimize corporate dominance over the work of mobilization agencies and ensure that the process of transformation strengthens, rather than weakens, worker organization and power. Most importantly, the wartime experience makes clear that the fight for a Green New Deal is best understood as a new front in an ongoing class war, and that we need to strengthen our own capacity to wage a serious and well-prepared ideological struggle for the society we want to create.