We had to tear this mothafucka up: The legacy of the LA Uprising

By Doug Enaa Greene & Shalon van Tine

June 19, 2020 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from Left Voice — The L.A. Uprising began after the beating of African American construction worker Rodney King. On March 3, 1991, the LAPD pulled over King, and four police officers beat him within an inch of his life. What made King’s case unique compared to other examples of police brutality was that his beating was caught on tape. That footage quickly spread across the country. The police attempted to justify their abuse of power, falsely claiming that King was on PCP and that he had attacked them. Anger was so widespread that prosecutors charged the officers in question, hoping to appease the public outcry.

However, a “not-guilty” verdict was all but guaranteed when the venue was moved to the virtually all-white Simi Valley. On April 29, 1992, the officers were acquitted of all charges. It was not the only example of justice denied. Thirteen days before King’s beating, a 15-year-old Black girl, Latasha Harlins, was killed by Korean convenience store owner Soon Ja Du, who accused her of stealing orange juice. Ja Du received no jail time for the murder, but just probation and community service. These events seemed to be just more examples of the systemic injustice that these communities had experienced time and time again.

Fuck the Police

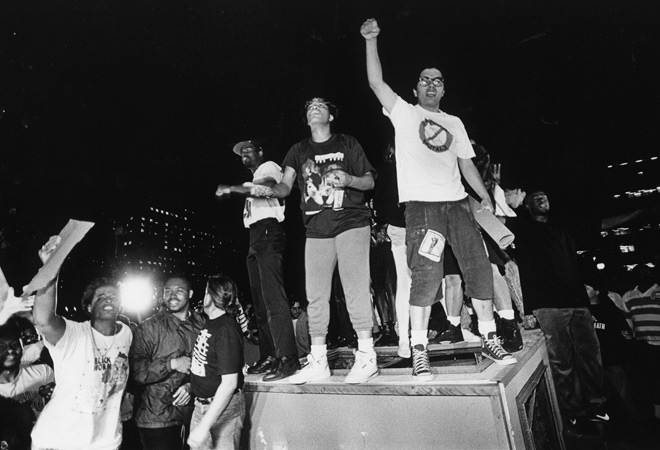

During the course of the trial, Rodney King had become a symbol of the daily experience of Black youth on the L.A. streets, who had known nothing except brutality from the LAPD, exacerbated by social tensions caused by rampant unemployment and poverty. Now the people refused to accept the court’s verdict and delivered their own. In less than an hour after the verdict, hundreds of people gathered in the streets outside of stores and in front of police stations. They shouted “No Justice! No Peace!” and “Fuck the Police!”

The anger boiled over into action. The result was five days of revolt throughout L.A. Residents looted and destroyed local businesses. The brunt of the property damage was made to Korean-owned enterprises. According to Mike Davis, Korean Americans were seen as a “middleman community between people in the ghetto, Black and Mexican, and big capital.” The crowd overturned cars, burnt the American flag, and flipped over at least one police car. In the downtown area, protesters attacked symbols of power, such as City Hall, courthouses, and the offices of the rightwing L.A. Times. Police attacked protesters, who fought back by tossing bricks and bottles at them.

The uprising was not just a Black revolt against white supremacy and police brutality, but a multi-racial uprising. For years, the cops had used the justification of “gang warfare” to terrorize Black and Latino neighborhoods. In 1987, Police Chief Daryl Gates instituted “Operation Hammer,” a wide-reaching anti-gang effort that allowed the LAPD to justify more intensive policing in Black and Latino communities. But during the revolt, the warring gangs of the Bloods and the Crips declared a truce. The truce not only ended a decade of fighting between the gangs, but helped direct their justified anger against the system. Fearing gang unity, the LAPD intentionally undermined the truce to fuel conflict between them. But the uprising could not be stopped — Blacks, Whites, Latinos, and Asians all took part in the looting and laying siege to LAPD headquarters at Parker Center. In the arrests that followed, 52 percent were Latino, 10 percent were White, and 38 percent were Black.

On May 1, Governor Pete Wilson called for federal assistance. President George H. W. Bush invoked the Insurrection Act, federalizing the California Army National Guard. Alongside the National Guard, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps (numbering more than 20,000) were all sent in to “restore order” by intimidating the communities.

By the time the rebellion was put down five days later, the uproar had resulted in 63 deaths, nearly 2,400 injuries, and almost $1 billion in property damage and financial losses. While L.A. was the epicenter of revolt, there were smaller protests in San Francisco, Las Vegas, New York, and Atlanta that rose up in support of their brothers and sisters in L.A.

Cultural Uprising

Even though the rebellion was short-lived, its legacy had a huge impact on American culture. When Spike Lee released the film Malcolm X later that year, he recut the famous introduction of the flag burning to include footage of the rebellion while viewers could hear a voiceover of one of Malcolm X’s speeches. That same year, just months after the uprising, Ice Cube released his album The Predator, which dealt directly with events from the rebellion, especially focusing on issues regarding economic marginalization, racial tensions between African Americans and Korean Americans, and police violence. In the track “We Had to Tear This Mothafucka Up,” Ice Cube raps that he “can’t trust a cracker in a blue uniform.” In “When Will They Shoot,” he adds: “To us, Uncle Sam is Hitler without an oven, burnin’ our Black skin, buyin’ my neighborhood then pushin’ the crack in.” Dr. Dre’s classic album The Chronic came out just a month later and explicitly described the need for rebellion, with Daz Dillinger singing: “Them wonder why me violent and don’t really understand the reason why me take me the law in me own hand.”

A whole slew of art and music arose to preserve the memory of the L.A. Uprising. Musicians across all genres created songs remembering the rebellion: Sublime, En Vogue, Bratmobile, Rage Against the Machine, to name a few. Tupac Shakur wrote the song “Keep Ya Head Up” and dedicated it to Latasha Harlins. Pioneering artist Thornton Dial painted Top of the Line (Steel), an abstract expressionist piece that captured the frenzy and the violence of the uprising. However, it is not just the artistic outpouring that should be remembered, but the militancy. The L.A. Uprising proved that this ingrained system of oppression must be met head on, that the “justice” system only protects those in power, and that the only way to dismantle the system is by force.

The Legacy

Until the recent Minneapolis uprising, the L.A. Uprising was the largest civil disturbance in the United States since the 1960s. Like the insurrection of 2020, the rebellion demonstrated that millions of people have said “Enough!” Yet unlike the Rodney King Rebellion, the current wave of protests has the potential to finally force the abolishment of the police, a system that was created to protect the property of the wealthy by suppressing striking workers — not to protect the people. Plus, the powers of technology were limited in 1992: the internet was new, there was no social media, and no one had camera phones. This technology can be used today to document police violence and spread the footage unlike ever before. By keeping the fires burning (both figuratively and literally), the current uprising can carry on the legacy of the L.A. Uprising until the police have been dismantled once and for all. Both in 1992 and in 2020, the uprising spurred people to rebel, to develop a required sense of combativity against the system, to create revolutionary art, and to harness the potential power of multi-racial unity to challenge the ruling class.

But there is another crucial lesson from the 1992 L.A. Uprising. It could only go so far. The spontaneous power and anger of the crowd was not harnessed into an organization with a clear program and the ability to operate on a mass scale. While falling short, what happened in 1992 showed that the people have power. It showed that the people were paying attention. And it showed that the fate of “the wretched of the Earth” is never a law of nature — when people fight back, it can be revoked.

Doug Enaa Greene is an independent communist historian, who is the author of Communist Insurgent: Blanqui's Politics of Revolution and a forthcoming biography of DSA founder Michael Harrington.

Shalon van Tine is a Ph.D. student in cultural and intellectual history at Ohio University and an adjunct instructor in history and the humanities at University of Maryland Global Campus.