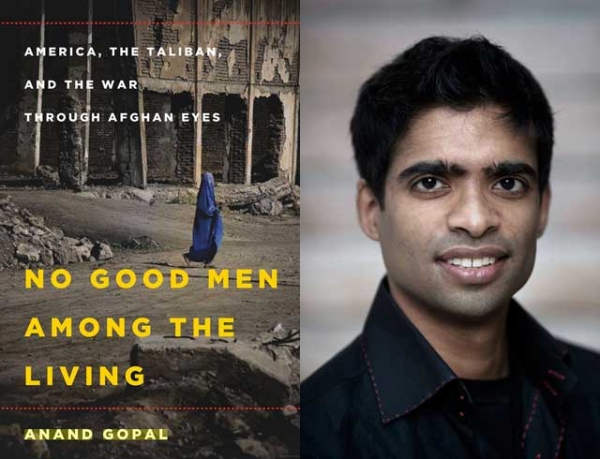

Why the Taliban won: A review of 'No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban and the War through Afghan Eyes'

No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban and the War through Afghan Eyes

By Anand Gopal

Picador, New York, 2014

Reviewed by Chris Slee

This book, published seven years before the Taliban took control of Kabul for a second time in 2021, helps explain their victory.

Anand Gopal, who worked as a reporter in Afghanistan for several years, talked to a diverse range of people — including officials of the US-backed government, Taliban fighters and ordinary villagers. This enabled him to see the reality behind US claims of progress.

Gopal says that in the immediate aftermath of the October 2001 US invasion, the Taliban collapsed. Many of their fighters, shocked by the technological superiority of the US military, deserted and either returned to their villages or fled to Pakistan. Many were willing to cooperate with the new regime installed by the US. Even Taliban leader Mullah Omar offered to surrender if he was allowed to "live in dignity" afterwards [p. 47]. The US ignored this offer.

However, the corrupt politicians and brutal warlords who dominated the new regime soon antagonised the population to such an extent that armed resistance began to grow. Former Taliban fighters took up arms again. They were able to recruit new followers, particularly in rural areas in the south of Afghanistan.

One of the people Gopal spoke to was Akbar Gul. In 2001, he was the commander of a Taliban unit fighting the Northern Alliance, a coalition of US-backed militias in northern Afghanistan. When Akbar Gul's unit was largely wiped out by US bombing, he deserted and fled to Pakistan.

He later returned to Afghanistan. After trying unsuccessfully to get a job as a police officer with the new regime, he worked as a sales assistant at an electronic goods stall. After teaching himself to repair mobile phones he set up his own stall.

However, the new police force, which Gopal describes as "an amalgamation of old militias and gangs" [p. 190], began to rob him, turning up at his stall and demanding "taxes". This was common practice: the police were robbing the people and raping women and boys.

Eventually the actions of the police drove Akbar Gul to rejoin the Taliban. Many other former Taliban fighters did likewise.

The actions of the US military also caused people to join the Taliban. Villages were bombed by the US Air Force or raided by US troops who broke down doors and arrested people accused of supporting the Taliban. At first the accusations were almost always false, but the raids antagonised people and caused some to begin supporting the Taliban.

Often US-backed warlords used the US armed forces to eliminate their personal enemies, whether these were rival warlords, business competitors, or elected local leaders. A warlord would falsely accuse someone of belonging to the Taliban. The US would then attack the village where this person lived.

One such warlord was Gul Agha Sherzai. Gopal describes his methods as follows: "Eager to survive and prosper, he and his commanders followed the logic of the American presence to its obvious conclusion. They would create enemies where there were none, exploiting the perverse incentive mechanism that the Americans—without even realizing it—had put in place. Sherzai's enemies became America's enemies, his battles its battles. His personal feuds were repackaged as 'counterterrorism', his business interests as Washington's".[p. 109]

Another warlord was Jan Muhammad, who was appointed governor of Uruzgan province in 2002. Gopal, who got to know him fairly well, explains how he benefited from the US presence: "Like Sherzai in Kandahar, he leased land—which wasn't his—to the US military for a base and supplied fellow tribesmen as construction workers. The instant profits were reinvested in the buildup of a private army, another Afghan Blackwater, a force under his control but rented out to the US military. He diversified his portfolio to include development work and trucking and, like any good Uruzgani landowner, opium". [p. 126]

Women still oppressed

The US invasion affected women differently in different parts of the country.

In Kabul, the end of Taliban rule brought some improvements. Women made gains in areas such as education and employment.

But in rural areas controlled by US-backed warlords, the situation of women often failed to improve and even became worse.

Gopal describes in detail the experiences of an Afghan woman called Heela. She was a student at Kabul University in the 1980s. At that time Afghanistan was ruled by a leftist government, which introduced progressive reforms and had some support in the cities. However, this government was also very repressive and alienated much of the population.

War broke out between the government, backed by the Soviet Union, and reactionary rebels known as the mujahideen, who were backed by the United States, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

In 1989, the Soviet Union withdrew its troops. In 1992 the government collapsed and the mujahideen entered Kabul.

The new rulers imposed severe restrictions on women. Their supreme court decreed: "Women are not to leave their homes at all, unless absolutely necessary, in which case they are to cover themselves completely; are not to wear attractive clothing and decorative accessories; are not to wear perfume or jewellery that makes any noise; are not to walk gracefully or with pride in the middle of the sidewalk; are not to talk to strangers; are not to speak loudly or laugh in public; and they must always ask their husband's permission to leave the home." [p. 59]

It was the mujahideen, not the Taliban (that did not yet exist), who imposed these rules. Many of the same mujahideen commanders would be returned to power after the US invasion in 2001.

To make matters worse, different mujahideen factions fought each other in a civil war lasting from 1992 to 1996. To escape the violence in Kabul, Heela and her husband Musqinyar fled to his home village in Uruzgan province. But here too there was conflict between rival warlords.

When the Taliban took over Uruzgan in 1995, they brought relative peace. There was little change in social customs, which were already very conservative. Women were confined to their homes. On the rare occasions when they went out, they wore a burqa and were accompanied by a male guardian.

When the Taliban were defeated in 2001, there was once again little change in the position of women. Women were still confined to the home. Girls' schools usually existed only on paper, not in reality.

When a presidential election was held in 2004, Heela got a job helping with voter registration. On election day she managed the woman section of the local polling station. She told Gopal that, apart from herself, "I didn't see a single woman vote". [p. 158]

Soon afterwards, Musqinyar was murdered by police for denouncing their corruption. The US blamed the Taliban.

Heela fled the village. After moving several times, she went to Tirin Kot, the capital of Uruzgan province, where she got a job with a medical NGO. When the Taliban found out, they initially ordered her to stop working, but then allowed her to continue if she got medical supplies for them. She agreed. According to Gopal: "So long as the Taliban left her and her family alone, so long as they dealt with her respectfully, she had nothing against them". [p. 248] She understood why people would rebel against warlords such as Jan Muhammad.

In 2009 Heela ran for election to the provincial council. She received only two percent of the votes, but was elected because two seats out of twelve were reserved for women. Gopal describes the election as a "charade", because of widespread ballot-stuffing: "In most of Uruzgan, there had hardly been anything resembling an election at all". [P. 264]

According to Gopal, the Afghan state was "one of the most corrupt in the world". [P. 273], adding that "American patronage was ultimately responsible for the mess". [p. 274]

He notes that: "Of the $557 billion that Washington spent in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2011, only 5.4 percent went to development or governance. The rest was mostly military expenditure, a significant chunk of which ended up in the coffers of regional strongmen like Jan Muhammad". [p. 273]

It is not surprising that the corrupt US-installed regime collapsed when US troops left.