Uganda: How the West brought Idi Amin to power

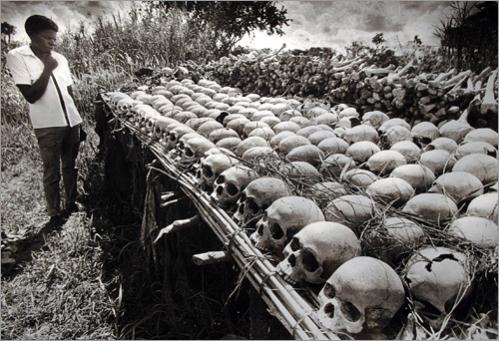

Some of the victims of the Idi Amin regime recovered by local farmers in the fertile fields of the Luwero Triangle region north of the Ugandan capital of Kampala in 1987.

Introduction by Tony Iltis

March 22, 2012 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – The reception in Uganda to the KONY 2012 viral video has been unanimously negative. From journalists, academics and bloggers to local NGO workers and local people at a public screening in the northern town of Lira, Ugandans have reacted angrily to their country’s politics and problems being simplified into a childish narrative to serve foreign propaganda needs.

Many Ugandan commentators noted that this is not the first time Uganda has suffered this treatment from Western filmmakers, citing the highly successful, award-winning 2007 British film, The Last King of Scotland, as another example. This film is centres on Idi Amin Dada, who ruled Uganda from 1971 to 1979 in a violent reign of terror that cost 100,000 lives.

The Last King of Scotland basically revived for a new generation what was already a standard narrative. Amin’s outlandish statements, absurd self-aggrandisement (awarding himself titles such as “Conqueror of the British Empire”) and the fact that while most dictators are content to employ others to kill and torture he took a more hands-on approach, made him the archetype of the post-colonial dictator.

Underlying this narrative is racism and post-facto justification of colonialism: the implication being that if you allow Africans to rule African nations, this is what they do.

However, as the article below by Pat Hutton and Jonathan Bloch, originally written in 1979, adapted for Zed Press in 1980 as part of the book, Dirty Work 2—The CIA in Africa, and republished in the February 2001 New African, clearly demonstrates, Amin was installed and maintained in power by Western powers.

While the article focuses on the British role, British government documents declassified in 2002 suggest that while Britain welcomed Amin’s coup and immediately supported the new régime, London was initially taken by surprise, the coup having been carried out by Israel.

As the article explains, Amin was central to Israel’s operations in the 1960s supplying arms to the Anya-Nya rebel group in southern Sudan. As a declassified post-coup communication from the British High Commission in Uganda explained: “The main Israeli objective here is to ensure that the rebellion in southern Sudan keeps on simmering for as long as conditions require the exploitation of any weakness in the Arab world. They do not want the rebels to win. They want them to keep on fighting.”

Amin had risen to the top of the Ugandan military as an ally of President Milton Obote. However, their subsequent falling out had led to Obote planning to move against Amin, endangering Israel’s operations, which was the motive of the coup.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a temporary cessation in the conflict between the South Sudanese rebels and the Sudanese state. This caused Israel to lose interest in Amin and become unresponsive to his ever-increasing demands for military hardware. In response Amin expelled Israeli military advisors and turned to the regime of Muammar Gadaffi in Libya for support.

Relations between Amin and Israel worsened in 1978, following the hijacking of an Air France airliner on a Tel Aviv to Paris flight to Entebbe Airport in Uganda. Amin claimed to be playing the role of negotiator but the Israelis suspected him of siding with the hijackers and launched a dramatic military rescue. Whatever the truth, once again the narrative was hijacked by Western movie makers.

Two Hollywood blockbusters were released very shortly afterwards: Victory at Entebbe in 1976 and Raid on Entebbe in 1977. These films did much to establish Israel’s version of events in popular historical memory, for example the claim that the hijackers separated Jewish from non-Jewish hostages. However, as Israeli hostage Ilan Hartuv told the July 8, 2011, Ha’aretz: “The terrorists separated the Israelis from the non-Israelis. The separation was done based on passports and ID cards. There was no selection of Jews versus non-Jews.”

While Britain and Uganda broke diplomatic relations in 1976, as the article below explains covert British support for Amin continued until his overthrow with the help of Tanzanian forces in 1979.

Uganda’s nightmare did not end with the overthrow of Amin. In the ensuing civil war, which lasted until 1986, 500,000 people were killed. The worst atrocities occurred during Obote’s second presidency, which lasted from 1981 to 1986. It was out of this war, known as the Bush War, that both the current Ugandan government of Yoweri Museveni and Joseph Kony’s Lords Resistance Army emerged.

It is against this record of Western indifference to the Ugandan people that naïve calls for Western military help to “save” Ugandans should be judged.* * *

By Pat Hutton and Jonathan Bloch

That Idi Amin was a brutal dictator of extraordinary cruelty is well known and becomes more so as the tally of his victims, according to conventional accounts, topped over 100,000 between 1971-75. What is less known is the role of the British government and its allies not only in maintaining Amin's machinery of repression but in actually establishing him in power. Although Amin later became alienated from his Western friends, we can show here that the break between him and Britain became complete only when his fall (on April 10, 1979) was imminent, and that regarding him as the least evil option from the point of view of British interests, London actively helped keep him in power.

The tale of how the Western powers took measures to reverse the

decline of their fortunes in Africa during the 1960s is complex in

detail but simple in principle. In Uganda, once dubbed the Pearl of

Africa

by Winston Churchill, huge British financial, industrial

and agricultural interests were under threat from the Obote

government.

Unease about Obote's intentions was combined with attempts by outside interests to ingratiate themselves. Obote accepted aid from the Israel government, which was desperately trying to avoid total diplomatic isolation while being used as a proxy by the United States in countries where its own reputation was tarnished.

The Americans and Israelis worked in very close co-operation in Uganda, particularly through their respective intelligence agencies, the CIA and Mossad. Washington provided some development aid while Israeli troops trained the Ugandan army and airforce. The British economic and political presence was always predominant and this was one of the situations that Obote hoped to change.

Throughout the late 1960s, Obote was consolidating his personal power

and introducing legislation that was to shake the colonial

interests. Although Obote was no Fidel Castro or Julius Nyerere [president ofTanzania], his Common

Man's Charter

and the nationalisation of 80 British companies

were not welcome in London.

As one prominent commentator put it: The Obote government was on

the point of changing not only the constitution but the whole

political system when [Amin's] coup occurred.

A vital source of raw materials, Uganda was not about to be permitted to determine its own political development at the expense of the entrenched interests. Soon, plans were being laid by Britain in combination with Israel and America to remedy this situation.

The grand plan

The first task was to choose Obote's possible successor, and Idi

Amin proved an obvious choice. Known by the British as a little

short on the grey matter

though intensely loyal to Britain

,

his qualifications were superb. He had started his career as a

non-commissioned officer in the British colonial regiment, the

King's African Rifles, and later served in the British suppression

of Kenyan nationalists in the late 1950s (mistakenly known as the Mau

Mau rebellion).

In Uganda itself, Amin had helped form the General Service Units (the political police) and had even chosen the presidential bodyguard. Some have said Amin was being groomed for power as early as 1966 (four years after Ugandan independence on October 9, 1962), but the plotting by the British and others began in earnest in 1969 when Obote started his nationalisation program.

The plotting was based in southern Sudan, in the midst of a tribe that

counted Amin among its members. Here, the Israel government had been

supporting a secessionist movement called the Anya-Nya against the

Arab-leaning Sudanese government, in an effort to divert Arab military

forces from Israel's western front with Egypt during the no

peace, no war

period of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

One of those helping the Anya-Nya was Rolf Steiner, a German mercenary veteran of several wars, who told of his time there in a book published in 1978, The Last Adventurer. Steiner said that he had been introduced to representatives of the giant Roman Catholic charity, Caritas International, and referred by them to two British men who would help him provide assistance to the Anya-Nya. They also suggested that Steiner keep in touch with a British mercenary called Alexander Gay.

Steiner had made Gay's acquaintance when they were both serving as mercenaries on the Biafran side during the Nigerian civil war. A former bank clerk, Gay had fought in the Congo from 1965 to 1968 and then in Nigeria, where he met the famous novelist Frederic Forsyth, then a war correspondent.

Forsyth had stood bail and given character references for Gay in November 1973 when Gay was tried for making a false statement to obtain a passport and for possession of a pistol, ammunition and gelignite (a type of dynamite).

On conviction, Gay was sentenced only to a fine and a suspended

sentence. One of the factors leading to this leniency may have been

that the British Special Branch had praised him in court and testified

that he had provided information which was great and considerable

help to Western powers

.

However, back in East Africa, Gay, Steiner and their British mercenary friends established themselves in southern Sudan with a radio link to their other base in the Apollo Hotel in Kampala, Uganda. But Steiner said he did not know of the real intentions of his British colleagues until he heard Gay had been casting aspersions on him to the Anya-Nya leadership.

In a confrontation over this, Steiner forced Gay to tell him what his real task was—to overthrow or assassinate Obote. The British government had no interest in supporting a southern Sudanese secession and was only using the Anya-Nya as cover for its plans for the future of Uganda.

Steiner said that he wanted to know more, so he made Gay come with him

to Kampala to search the room of one of their British colleagues at

the Apollo Hotel, Blunden (a pseudonym Steiner uses for this former

British diplomat

now turned mercenary). They came away with a mass

of coded documents detailing the British plot that had been

transmitted to London by the British embassy.

Steiner says in his book that Gay explained to him why Obote's

successor had been chosen, saying: Blunden told me that the British

knew Idi Amin well and he was their first choice because he was the

stupidest and the easiest to manipulate.

As Steiner remarks:

Events were later to prove who was the most stupid.

Little more is known about this episode except that Steiner claims that Blunden was operating an airline called Southern Air Motive, and had planned the December 18, 1969, assassination attempt on Obote. It has since been independently confirmed that Gay and Blunden were working for British intelligence, and also that Steiner found British intelligence code books at the Apollo Hotel.

The Israeli connection

That it was the Israelis who were providing so much help to the Anya-Nya while the Britons plotted against Obote lends support to the allegations of a former CIA official in March 1978 that Amin's coup was planned by British intelligence in cooperation with Israeli intelligence. Amin was known to have visited southern Sudan at least twice in 1970, once in disguise, and was in constant touch with the Anya-Nya rebels.

One of Amin's Israeli friends has spoken of his role in the coup

and how he helped Amin. The friend

who was a colonel in the

Israel army, said that Amin approached him, saying he feared that

people loyal to Obote would be able to arrest and kill him before he

could secure Kampala. The friend

said he told Amin that troops

from Amin's own tribe in southern Sudan should be on hand, as well

as paratroopers, tanks and jeeps.

Bolstered by the Israeli assistance and the greater power of the Ugandan tank corps, Amin was able to overwhelm the majority of the armed forces loyal to Obote on January 24-25,1971. The Anya-Nya troops were a core of the forces in the Amin coup, and thousands of them later joined the Ugandan army and carried out many of Amin's early bloody purges which saw more than 100,000 Ugandans killed between 1971-75.

The Israelis had clearly been cultivating Amin for some time through their military presence in a manner consistent with their role as US proxies. These times were the heyday of the CIA's worldwide efforts to subvert radical regimes and in Africa to assert the predominance of the US as far as possible. Active in Kenya, Ghana, Mozambique, Tanzania and Nigeria, the United States was also seeking to gain influence in Uganda, especially by means of intelligence officers of the navy and airforce based in Kampala, together with the CIA agents working under the cover of USAID.

One of the features of Amin's coup was its similarity to the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana in February 1966. Like Obote, Nkrumah had been putting forward nationalisation measures and, when on a visit abroad (like Obote), was toppled by a coup which had the hands of the CIA all over it. Former CIA officers have since written books crediting the agency with the Ghana coup. Interestingly, Obote was a staunch supporter of Nkrumah who, during his exile in Guinea after his overthrow, recorded in his letters the financial support he had received from Obote's government for his upkeep in Guinea.

The Amin coup

Just a few days before the coup, 700 British troops arrived in

neighbouring Kenya. Although they were apparently scheduled to arrive

long before, The Sunday Express speculated that they would be used to

put down anti-British riots following the decision of the British

Conservative government to sell weapons to apartheid South Africa,

remarking that the presence of the troops, seemingly

co-incidental—could prove providential

. The paper added that

the British troops would be used if trouble for Britons and British

interests starts

.

The report was followed two days later, still before the coup, by strenuous denials.

When the coup took place, Obote was attending the Commonwealth conference in Singapore. He was aware that the internal situation in Uganda was not to his advantage and went to the conference only because President Nyerere of Tanzania had impressed on him the importance of being there to help present effective opposition to the British government's arms sales to apartheid South Africa.

The African members of the Commonwealth were piling the pressure on

the British government. At a meeting with Zambia's Presidents Kaunda, Nyerere

and Obote, British Prime Minister Edward Heath was threatened

with the withdrawal of those countries from the Commonwealth should

the South African arms decision go through. During this tempestuous

meeting, Heath is reported to say: I wonder how many of you will be

allowed to return to your own countries from this conference.

When Amin finally struck, the British press claimed that a Ugandan sergeant-major operating a telephone exchange had overheard a conversation concerning plans by Obote supporters in the army to move against Amin. Upon hearing the news, Amin moved into action, quickly seizing all strategic points in Uganda. Apart from the fact that the army would not have attempted to remove Amin in the absence of Obote, this version ignores the British and Israeli plans.

On Amin's accession to power, all was sweetness and light between him and the British establishment. Britain very quickly recognised Amin's regime, exactly one week after the coup. And he was hailed as a conquering hero in the British press. But even the US government considered the British recognition of Amin as showing unseemly haste.

In London, The Times commented: The replacement of Dr Obote by

General Amin was received with ill-concealed relief in Whitehall.

Other British press comments included, Good luck to General

Amin

(the Daily Telegraph); Military men are trained to

act. Not for them the posturing of the Obotes and Kaundas who prefer

the glory of the international platform rather than the dull but

necessary tasks of running a smooth administration

(the Daily

Express); and more in the same vein.

Not surprisingly, Amin supported Edward Heath's stand on selling arms to apartheid South Africa, breaking the unified opposition of the states at the Singapore Commonwealth conference.

Amin also denationalised several of the British companies taken over under Obote, and in July 1971 came to London where he had lunch with the queen and meetings with Heath's cabinet. But the seeds of discord between Britain and Amin were being sown as he began to fail to live up to their expectations of servility.

After the coup, Uganda was granted 10 million pounds in economic aid (to be

administered by Britain), in addition to 15 Ferret

and 36

Saladin

armoured cars, other military equipment and a training

team for the Ugandan army.

However, Amin resented the fact that Britain would not give him fighter aircraft and other sophisticated equipment to help his expansionist ambitions. In particular, Amin had plans for an invasion of Tanzania, so that he could have a port on the east coast of his own.

For help in this project, which was becoming an obsession, Amin then turned to Israel. He asked for Phantom jet fighters and other sophisticated weapons, permission for which would have been required from the US government.

Saying that the request went beyond the requirements of legitimate

self-defence

, Israel refused Amin, which probably was a factor in

the expulsion of the Israelis from Uganda in April 1972.

Although short of the hardware necessary, Amin was well supplied with strategic advice. This came from another collaborator with British intelligence, a British major who lived on the Kagera River, on the border with Tanzania, where Amin used to come to visit him frequently by helicopter.

This former officer in the Seaforth Highlanders had been a member of the International Commission of Observers sent to the Nigeria civil war to investigate charges of genocide, but he was sacked amid allegations that he had offered his services to the Nigerian federal government as a mercenary.

But at a National Insurance Tribunal in England, where he was

protesting his dismissal and claiming compensation, the major

explained that his real role in Nigeria was to collect intelligence

for the British government and offer strategic military advice to the

Nigerian federal forces. In spite of strenuous denials from the

Foreign Office, the tribunal accepted the major's story and

described him as a frank and honest witness

.

It is not known whether the major's activities on behalf of Amin were officially sanctioned by the British government, or parts of it, but his role seems to have been similar to the part he played in Nigeria. At any rate, the major took Amin's invasion plan of Tanzania seriously, undertaking spying missions to Tanzania to reconnoitre the defences and terrain in secret.

He supplied Amin with a strategic and logistical plan to the best of his abilities, and although lack of hardware was an obstacle, evidence that Amin never gave up the idea came in the fact that the invasion of Uganda by Tanzanian and exiled Ugandan anti-Amin forces in late 1978 which eventually brought his rule to an end on April 10, 1979, was immediately preceded by an abortive invasion of Tanzania by Amin's army.

In the manner which characterised the major's behaviour after the

Nigerian episode, he did not maintain discretion when back in

England. He wanted to publish his story of cooperation with Amin in the Daily Express, but this was scotched by an interesting move by the

British government – a D-Notice

banning the story on grounds of

national security.

US support

Beginning with his purges of the army, later extending them to those

who had carried out the purges, the ferocity and cruelty of Amin's

rule increased steadily—most of it performed by the dreaded

Public Safety Unit

, the State Research Centre

and

various other bodies. These received training assistance and supplies

from Britain and the US.

In July 1978, the US columnist Jack Anderson revealed that 10 of Amin's henchmen from the Public Safety Unit were trained at the International Police Academy in the exclusive Washington suburb of Georgetown. The CIA-run academy was responsible for training police officers from all over the world until its closure in 1975.

Three of the Ugandans continued their studies

at a graduate

school, also run by the CIA, called the International Police Services

Inc. Shortly after the Amin coup, the CIA had one full-time police

instructor stationed in Uganda. Controversy raged in the United States

in the use of equipment sold to Uganda. Twelve of these were police

helicopter pilots for American Bell helicopters that had been

delivered in 1973.

Security equipment of various types also found its way to Uganda from Britain, and most came as a result of the groundwork done by another collaborator of British intelligence, Bruce Mackenzie, an ex-RAF pilot and long-serving adviser to President Kenyatta of Kenya.

Mackenzie also doubled as the East African agent for a giant British electronics firm, based in London, dealing in telecommunications. Trade in radio transmitters and other devices continued right up to Amin's fall from power. Though Mackenzie had died when a bomb planted by Amin's police exploded in his private plane, the trade with the electronics firm continued nonetheless.

Several times a week, Ugandan Airlines' planes would touch down at Stansted Airport in Essex, England, to unload quantities of tea and coffee and take on board all the necessary supplies for Amin's survival.

In spite of all the revelations of the nature of Amin's dictatorship and his dependency on the Stansted shuttle, it continued right up to February 1979, when the British government ended it in an extraordinary piece of opportunism. The chief advantage of the shuttle to Amin was that it obviated the need for foreign exchange, for which Uganda had virtually none.

In June 1977, the Sunday Times revealed that the Ugandan planes to Stansted were picking up Land Rovers (28 were delivered), one of them specially converted and bristling with sophisticated electronic equipment for monitoring broadcasts, jamming and other capabilities.

The cargo spotlighted by the Sunday Times also included a mobile radio studio, which is almost certainly where Amin was continuing to assert over the airwaves that he was in control long after he had been ousted from Kampala.

At the same time, an extensive relationship between Uganda and the Crown Agents, the trading agency with strong links in Britain's former colonies, was exposed. Crown Agents had arranged a deal for Amin to buy 120 three-ton trucks made in Luton. The trucks were thought to have been converted for military purposes before being shipped out. The British firm that supplied the electronic equipment and another firm in the same field had also supplied Amin's State Research Centre with telephone-tapping equipment, night-vision devices, burglar alarms and anti-bomb blankets.

When the Liberal MP David Steel questioned Labour Party Prime

Minister Jim Callaghan about this, all that the prime minister had to say

was that the devices were intended to track down television licence

dodgers

. To add to this, it was said that after the Entebbe raid

by Israeli troops, the radar damaged there was sent to England for

repair.

The principal value of the Stansted shuttle was to maintain Amin's system of privileges, vital for retaining the allegiance of the Ugandan army. His power elite, consisting of army officers not subject to the stringent rationing imposed on the rest of the population, depended on the goods brought in on the Stansted shuttle.

During times of the frequent and widespread shortages of basic commodities linked to inflation of around 150%, the officers could use the British goods to make their fortunes on the black market.

A further aspect of the Stansted shuttle involved British, US and Israeli intelligence: this was in the provision of the planes. According to the Washington Post's Bernard Nossiter, Pan Am was instructed by the CIA to sell several Boeing 707s to a New York-based Israeli company with former US defence department connections. The company was owned by an Israeli multimillionaire with a vast commercial empire.

The company sold one of the Boeings to a small firm based in

Switzerland, which passed the plane on to Amin in May 1976. The

function of the Swiss-based company was to act as a laundry

for

the financing of projects backed by Israeli intelligence.

In 1977, the Israeli company which had originally bought the plane from Pan Am, wanted to sell another Boeing to Uganda Airlines, but with the notoriety of Amin's regime getting worse, the company feared losing the US State Department approval it had won for the first deal.

The plane was thus sold to another company housed in the same building in New York as the Israeli company, which then leased the plane to Uganda Airlines. The two companies had close ties, and the purpose of this extraordinary generosity was to spy on the Libyan military airfield in Benghazi, where the planes always refuelled before going on to Stansted.

Both Israeli and US intelligence provided navigators

for

the planes to spy on the airfield and make reports which were shared

out among Israeli, US and British intelligence agencies. The information

was probably of very little use, since the Libyans almost certainly

knew of the presence of the navigators

on the planes. But Amin

was getting a very cheap service for the coffee and tea bound for

London and the other goods that returned. Washington also provided

pilots for the planes. A California-based company supplied the pilots

acting as a subcontractor.

Britain, a friend to the last

In general, the British government's attitude to Amin's regime

was neatly summed up by The Times when Amin had just expelled Uganda's Asians on August 9, 1972: The irony is that if President

Amin were to disappear, worse might ensue

, The Times said. In a similar comment, exemplifying the relationship with Amin as being

the devil you know

, The Economist stated: The last

government to want to be rid of Amin is the British one.

This attitude persisted even beyond the break in Ugandan-British diplomatic relations in July 1976, as shown by the fact that the Stansted shuttle continued. Important political commentators in the British press believed that London would not impose sanctions on Uganda under Amin, since this might set a precedent for sanctions against apartheid South Africa. Britain plainly considered the bad image consequent on maintaining links with Amin not as serious as the consequences of breaking links with South Africa.

Nonetheless, as the body count of Amin's victims—former friends, members of the clergy, soldiers and mostly ordinary people—mounted daily, stock should have been taken of those who helped Amin stay where he was and turned a blind eye to the amply documented brutality of his regime.

Thirty years on, no such stock has been taken and Amin continues to be

cast as the demented

dictator who had no friends.