Cuba: The legacy of the October 1962 Missile Crisis

By Ike Nahem

[This is the third in a series of articles by Ike Nahem. The first can be found HERE and the second HERE. For more articles on Cuba, click HERE.]

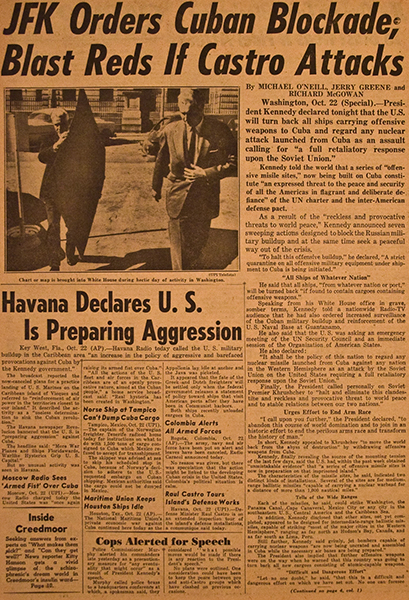

October 22, 2012 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – October 1962 marks the 50th anniversary of the so-called “Cuban Missile Crisis”. The last two weeks of that October was the closest the world has come so far to a widespread nuclear exchange.

(In August 1945, the United States government, having a then-monopoly on the “atom bomb”, unilaterally dropped nuclear bombs, successively, on the civilian inhabitants of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At the time of this clear war crime, Japanese imperialism’s conquests and vast expansion that began in the 1930s had shrunk sharply. The Japanese rulers were retreating under intense attack from rival imperialists and indigenous independence forces in their remaining occupied lands, including parts of Manchuria in China, as well as Korea, Vietnam and the “Dutch East Indies”, now Indonesia The Japanese navy was incapable of operations and the Japanese merchant fleet was destroyed. The Japanese government had begun to send out “peace feelers”, fully aware of its hopeless situation. Washington’s utterly ruthless action finalised the defeat of the Japanese empire in the Asian-Pacific “theatre” of World War II … and sent an unmistakable shock and signal to the world.)

The young leaders of the Cuban Revolution, now holding governmental power, were in the very eye of the storm during those two October weeks. The diffusing and resolution of the Missile Crisis – in the sense of reversing and ending the momentum toward imminent nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union – came when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gave way to US President John Kennedy’s demands and agreed to halt further naval shipments of nuclear missiles to Cuba and withdraw those already in Cuban territory. Khrushchev further agreed to the removal of Soviet medium-range conventional bombers, very useful to the Cubans for defending their coastlines and a near-complete withdrawal of Soviet combat brigades.

For his part, Kennedy made a semi-public conditional formulation that the US government would not invade Cuba (this was not legally binding or attached to any signed legal or written document) and also agreed, in a secret protocol, to withdraw US nuclear missiles from Turkey that bordered the Soviet Union.

The Cuban government, which had, at great political risk, acceded to the Soviet proposal to deploy Soviet nuclear missiles on the island, was not consulted, or even informed, by the Soviet government, at any stage of the unfolding crisis, of the unfolding US-Soviet negotiations. Furthermore, Cuban representatives were completely excluded and the five points Cuba wanted to see addressed coming out of the crisis and included in any overall agreement, ignored altogether under US insistence and Soviet acquiescence.

The entire experience was both politically shocking and eye opening for the Cuban revolutionaries. They came out of it acutely conscious of their vulnerability and angered over their exclusion.

(In a public statement on October 28, presenting the five points, Fidel Castro said, “With relation to the pronouncement made by the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, in a letter sent to the premier of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, to the effect that the United States would agree, after the establishment of adequate arrangements through the United Nations, to eliminate the measures of blockade in existence and give guarantees against any invasion of Cuba and in relation to the decision announced by Premier Khrushchev of withdrawing the installation of arms of strategic defense from Cuba territory, the revolutionary government of Cuba declares that the guarantees of which President Kennedy speaks--that there will be no aggression against Cuba--will not exist unless, in addition to the elimination of the naval blockade he promises, the following measures among others are to be adopted: 1) Cessation of the economic blockade and all the measures of commercial and economic pressure which the United States exercises in all parts of the world against our country; 2) Cessation of all subversive activities, launching and landing of arms and explosives by air and sea, the organisation of mercenary invasions, infiltration of spies and saboteurs, all of which actions are carried out from the territory of the United States and some other accomplice countries; 3) Cessation of the pirate attacks which are being carried out from bases existing in the United States and Puerto Rico; 4) Cessation of all the violations of our air and naval space by North American war planes and ships; and 5) Withdrawal of naval base of Guantanamo and the return of the Cuban territory by the United States”.)

Washington plans direct invasion

By April 20, 1961, the revolutionary Cuban armed forces, led by Fidel Castro, was victoriously mopping up on the coastal battlefields and detaining survivors from the routed counter-revolutionary Cuban exile “army” organised by the US government and its Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs (Playa Giron to the Cubans). The scheme to destroy the Cuban Revolution had been devised by the Dwight Eisenhower White House and carried out by the new Kennedy Administration in its third month after taking office.

Playa Giron was as humiliating and unacceptable for Washington as it was confidence building and invigorating for the Cuban revolutionaries. It was certainly no secret to anyone paying the slightest attention that not even a nanosecond passed between Washington’s debacle at the Bay of Pigs and the planning for a new invasion, this time directly by US forces without the proxy agency of the mercenary “troops” of the former ruling classes of Cuba, who were by then ensconced in southern Florida. Since October 1961 the Pentagon officers assigned to prepare for the US invasion of Cuba had been revising, updating and “polishing” the concrete details. These “operational plans” were continually reviewed with President Kennedy.

Cuba faced an imminent, violent one-two punch: intensive aerial bombardment followed by large-scale invasion on multiple fronts. It was less than 10 years from the last major US war, in Korea. The impact of US bombing on the northern Korean capital of Pyongyang, artificially divided in the aftermath of World War II, could not have been encouraging to the Cuban leadership. Virtually the entire city was flattened by carpet bombing: 697 tons of bombs were dropped on Pyongyang along with nearly 3000 gallons of napalm; 62,000 rounds were used for “strafing at low level”. According to Australian journalist and eyewitness to the carnage Wilfred Burchett, “There were only two buildings left standing in Pyongyang”. While the numbers of civilian deaths from the US assaults are inexact, well over 1 million Koreans in the north died, some 12-15% of the total population.

The “operational plans” for the US invasion of Cuba were to involve the initial dispatching of 90,000 troops and was projected to reach up to 250,000. This to deal with a country of 6 million people. (For comparison, the population of Vietnam was around 40 million during the years of the US war in the 1960s and early 1970s. US troop levels reached 500,000. Massive US military operations in the air and on the ground killed millions of Vietnamese, perhaps 10% of the Vietnamese population.) There is no question that once “the dogs of war” were unleashed, with the accompanying propaganda onslaught, Washington would wage a war of annihilation under the cover of “democratic” and even “humanitarian” verbiage. Cuban resistance would be fierce. Mounting US casualties would, in the initial period, feed war fever and US aggression. In short: Cuba faced unheard of death and destruction … and the clock was ticking.

By this time President Kennedy’s “Operation Mongoose” was in effect. “Mongoose” was essentially a large-scale terrorist campaign employing sabotage, bombings, murder and so-called “psychological warfare” inside Cuba. Kennedy’s cynical purpose was to undertake any means deemed necessary to disrupt and demoralise Cuban society through constant, incessant violent attacks and economic sabotage to the point where the social and political conditions would be created for a full-scale US invasion.

But Kennedy and his civilian and military “advisors” continued to underestimate both the calibre of the revolutionary leadership and the capacities of the Cuban working people and youth they were terrorising, as well as the revolution’s determination and competence to organise its defences. Above all, the US rulers were not used to facing such a politically savvy enemy. The young Cuban revolutionary government, with the indefatigable Fidel Castro as its main spokesperson, was adept and quick on its feet in effectively exposing to world public opinion Washington’s anti-Cuba campaign through a vigorous, factually accurate and public counter-offensive based on what the revolution was actually doing.

(The logic behind “Operation Mongoose” was bluntly laid out in an internal memorandum of April 6, 1960, by L. D. Mallory, a US State Department senior official: "The majority of Cubans support Castro ... the only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship ... every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba.” Mallory proposed "a line of action that makes the greatest inroads in denying money and supplies to Cuba, to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and the overthrow of the government”.)

On July 26, 1961 – the national holiday declared by the revolutionary government commemorating the July 26, 1953, attack led by Fidel Castro and Abel Santamaria on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba – the CIA attempted to assassinate Fidel Castro, Raul Castro and Che Guevara during the celebrations. The CIA plan was, if the murders were “successful”, to stage a provocation against the US base at Guantanamo and make it appear to be Cuban revenge for the murder of their top leaders. This would then be the pretext for a full-scale US invasion. Here on full display is the cynical mendacity operating at the top of the US government in the drive to bring back the power of the landowners, rich playboys, segregationists, gangsters and pimps – the full flower of “democracy” to the benighted Cuban masses suffering under literacy drives, free medical care, desegregated public facilities and the crushing of the US Mafia.

During the next month, August 1961, the CIA organised one of its most pernicious campaigns against the revolutionary government. Its agents spread lies through a built-up rumour bill that there was a Cuban government policy to take all children away from their parents by force and raise them in “state institutions”. Some 15,000 Cuban families, overwhelmingly from middle and upper classes full of prejudice and hostility to the revolution, panicked and sent their children mostly to the US in response to a big lie, under the CIA’s infamous “Operation Peter Pan”.

While all this criminal activity was going on, the Cuban Revolution advanced its program of social justice and human liberation for the oppressed and exploited majority as the most effective counterforce to the Yanqui aggression. On February 26, 1962, Cuba’s rejuvenated labour unions provided the people power for the campaign of Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Health to carry out a nationwide campaign of vaccination against polio. By the end of the year the disease was completely wiped out on the island. It took the United Nation’s World Health Organisation, then far more subject to pressure from Washington than now, 43 years to finally recognise that Cuba was the first nation in the Americas to accomplish this.

Things like this and the full array of revolutionary advances taking place in the face of Washington’s mounting terrorist campaign convinced General Maxwell Taylor, who oversaw Operation Mongoose with attorney general Robert Kennedy at the White House, that the terrorist operation, “mak[ing] maximum use of indigenous resources”, could not and would not do the job of overthrowing the revolutionary government. “Final success”, Taylor explained in a March 1962 report to President Kennedy, “will require decisive US military intervention”. US spies inside Cuba, at most, could help “prepare and justify this intervention and thereafter facilitate and support it”. With the Bay of Pigs debacle still fresh in his mind and without some of the blinkers of more gung-ho invasion advocates, Kennedy hesitated to give a green light to the invasion plans he has ordered up. It remained yellow-lighted however and Kennedy directed that Mongoose terrorism continue and step up.

The terrorist anti-Cuba campaign was not limited to Cuban territory. On April 28, 1962, the New York offices of the Cuban Press Agency Prensa Latina was attacked in New York, injuring three staff members. More seriously, from May 8-18, a “practice run” for the US invasion of Cuba took place. The full-scale “military exercise” was code named “Operation Whip Lash” and sent an unmistakable signal of intimidation from the US military colossus to the people of Cuba.

All this mounting imperialist intervention had only one possible ending point – short of a Cuban surrender, which would never come. Events were coming to a head in Washington, Moscow and Havana, events that ineluctably posed and placed the nuclear question in the equation.

In a major speech to a closed meeting of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) on January 25-26, 1968, reviewing the entire Missile Crisis, Fidel Castro stated that Cuba’s revolutionary leadership looked to the Soviet Union for “measures that would guarantee the country’s safety. In that period we had tremendous faith in the Soviet Union. I think perhaps too much.” While the Cuban government and overwhelming popular majority were mobilised, armed to the teeth and prepared to fight to the death, they wanted to live in peace and to enjoy the fruits of building a new society after a hard-fought revolutionary triumph. The Cuban leadership fully understood that a US invasion would kill many hundreds of thousands and destroy the Cuban infrastructure and economy. How to stop the coming US invasion was the burning question.

Khrushchev rolls the dice

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, the Soviet leadership was facing a decidedly negative nuclear relationship of forces vis-à-vis Washington. This position of inequality (in the framework of the aptly acronymed Mutually Assured Destruction – aka MAD – nuclear doctrine) was perceived in Moscow as an impediment to carrying out political negotiations and manoeuvring with Washington and the NATO powers and defending Soviet interests in the “geopolitical” Cold War arena.

By April 1962 15 US Jupiter nuclear missiles had been installed and were “operational” in Turkey on the border of the Soviet Union. “Operational” meant ready to launch at any moment. Each missile was armed with a 1.45 megaton warhead, with 97 times the firepower of the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The official estimate of the “fatality projection” for each missile was 1 million Soviet civilians.

The Jupiter deployment in Turkey added to the overwhelming US superiority in quantity and quality in the “nuclear arms race” between Washington and Moscow. According to Anatoly Gribkov, of the Red Army general staff (cited in the television program DEFCON-2 shown on the US Military Channel), “The United States had about 5000 [nuclear] warheads, the Soviet Union 300. And of those [300] only two or three dozen that could hit the United States.” Khrushchev decided to alleviate this “imbalance” by placing missiles on Cuba if he succeeded in selling the idea to the Cuban leadership.

(In the 1960 presidential election, the liberal Democrat Kennedy shamelessly promoted as an important campaign issue a supposed “missile gap” – in the Soviet Union’s favour – between Washington and Moscow, a conscious fabrication. Kennedy also postured to the right of his Republican opponent, Eisenhower’s vice-president Richard Nixon, on “getting tough with Castro”. On this, Nixon had the disadvantage, as Kennedy was no doubt aware, of being unable to publicly tout the Eisenhower White House’s already advanced plans for the mercenary invasion at the Bay of Pigs, which Kennedy carried out three months after his Inauguration.)

Sometime in the spring (April-May) of 1962 the Khrushchev government proposed to the Cuban government that Cuba receive nuclear-tipped missiles on Cuban territory. In no other country outside Soviet territory (including none of its “Warsaw Pact” allies, which were politically subordinate to the Soviet government) had the Soviet government located nuclear missiles. Washington, by contrast, had openly placed nuclear missiles in numerous western European countries as well as Turkey and secretly in Okinawa, Japan, aimed at China. (Both the United Kingdom and France, both US allies, also had nuclear arsenals by that time. China detonated its first nuclear bomb in an October 1964 “test”.)

Additionally, US “strategic” nuclear armed aircraft were in the air ready for attack orders 24 hours a day, seven days a week. US nuclear submarines were in similar mode and even more difficult to detect. While Soviet capabilities undoubtedly lagged behind the US, it was not so much as to preclude inevitable reciprocal attack in response to any US “first strike”. Soviet missiles in Cuba would theoretically be a further deterrent to any US “first strike” threat. Placing the missiles in Cuba was clearly seen by the Soviet government as a bargaining piece to advance Soviet strategic interests in the nuclear chessboard that animated US-Soviet “diplomatic” manoeuvres and intrigue.

Khrushchev evidently presumed that, faced with a fait accompli, Washington would redress the imbalance to the benefit of the Soviet Union. The Soviet missiles, upon being fully operational, would be able to strike major population centres and whole geographic regions of the US, roughly equivalent to the potential death-dealing capacity Washington had through its missiles in Europe surrounding and targeted on the Soviet Union. Of course, the big “if” in all of this reasoning was getting to the accompli. Given US technical proficiency this was a fantasy.

At the end of May 1962 the first direct presentation of the Soviet proposal was delivered to Fidel Castro and Raul Castro in Cuba by a Soviet delegation led by an alternate member of the Soviet Presidium (an executive decision-making body). The Soviet officials revealed to the Cuban leaders that their “intelligence” told them conclusively that a US invasion was being seriously prepared, to be implemented at any time over the next months. Of course, the Soviets did not tell the Cubans anything they did not already know in general, but there were new specific facts and details. The proposal to fortify Cuba’s defences and include the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles on the island led to intense consultations within the top Cuban leadership (the chief ministers involved were Fidel Castro, Raul Castro, Che Guevara, Osvaldo Dorticos, Carlos Rafael Rodriguez and Blas Roca). The day after the proposal was received the Cuban leadership told the Soviet delegation that the nuclear deployment was acceptable in principle.

In an interview with European journalist Ignacio Ramonet (from the book Fidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken Autobiography, published in 2006 by Scribner and based on extensive interviews with Castro by Ramonet) Castro referred to the discussions within the Cuban central leadership, saying that besides Khrushchev and the Soviet leadership’s “sincere desire to prevent an attack against Cuba … they were hoping to improve the balance of strategic forces… I added that it would be inconsistent of us to expect the maximum support from the USSR and the rest of the Socialist camp should we be attacked by the United States and yet refuse to face the political risks and the possible damage to our reputation when they needed us. That ethical and revolutionary point of view was accepted unanimously.”

In a speech many years later in 1992 Fidel Castro said, “We really didn’t like the missiles. If it had been a matter only of our own defense , we would not have accepted the deployment of the missiles. But not because we were afraid of the dangers that might follow the deployment of the missiles here; rather, it was because this would damage the image of the revolution and we were very zealous in protecting the image of the revolution in the rest of Latin America. The presence of the missiles would in fact turn us into a Soviet military base and that entailed a high political cost for the image of our country, an image we so highly valued” (cited in October 1962 the ‘Missile’ Crisis As Seen From Cuba by Tomas Diez Acosta, Pathfinder Press) .

Legality, secrecy and lies: Losing the high moral ground

Having agreed in principle, Fidel Castro, Raul Castro and Che repeatedly argued with the Soviet leadership that the deployment should be open and public. The fact was that there was nothing in the Soviet-Cuban agreement to deploy the missiles that contravened any existing international law. In any case, the Cuban leaders were certain that it would be virtually impossible for the shipment, site construction and land deployment to remain concealed from highly sophisticated US surveillance technology. Furthermore, on the face of it, given the US missiles in Turkey and Italy surrounding the Soviet Union and with practically public US plans to invade Cuba, open and transparent was the way to go politically and morally. All of this was rejected out of hand by the Khrushchev leadership and the Cuban leaders chose not to push the point. In his January 25-26 speech, Castro goes into scathing detail on how shocking, given the Soviet insistence on secrecy, the lack of discretion on the Soviet side was, crossing into outright recklessness, in the actual deployment of the missiles.

The Soviet operation was the largest seaborne operation in Soviet history. By the time of the missiles’ detection and Khrushchev’s decision to remove them under US pressure, there were already 134 nuclear warheads on the ground in Cuba. All three of the SS-4missile regiments were operational even as Soviet ships stopped moving towards Cuba.

In the book with Ramonet, Castro speaks of the “strange, Byzantine discussion” over whether Soviet arms shipments to Cuba were offensive or defensive. “Khrushchev, in fact, insisted they were defensive, not on any technical grounds, but rather because of the defensive purposes for which they’d been installed in Cuba… [We felt there was] no need to go into those explanations. What Cuba and the USSR were doing was perfectly legal and in strict conformity with international law. From the first moment, Cuba’s possession of armaments required for its defense should have been declared.

“We didn’t like the course the public debate was taking. I sent Che … to explain my view of the situation to Khrushchev, including the need to immediately publish the military agreement [on deploying the nuclear missiles in Cuba] the USSR and Cuba had signed. But I couldn’t manage to persuade him… For us, for the Cuban leaders, the USSR was a powerful, experienced government. We had no other arguments to use to persuade them that their strategy for managing the situation should be changed, so we had no alternative but to trust them.”

In the January 25-26, 1968, speech Castro bluntly expressed his viewpoint:

[Around July] we saw that the United States was creating an atmosphere of hysteria and aggression and it was a campaign that was being carried out with all impunity. In the light of this we thought the correct thing to do was to adopt a different position, not to get into that policy of lies: ‘we are sending Cuba defensive weapons.’ And in response to the imperialist’s position, the second weakness (or the first weakness) was not to stand up and respond that Cuba had every right to own whatever weapons it saw fit … but rather to adopt a policy of concessions, claiming that the weapons were defensive. In other words, to lie, to resort to lies which in effect meant to wave a basic right and principle.

Some 35 years later, in the Ramonet book, Castro returned to this crucial political approach, which is much more powerful than the usual technical cast of events when things had reached the stage of an actual nuclear standoff:

There was nothing illegal about our agreement with the Soviets, given that the Americans had missiles in Turkey and in Italy too and no one ever threatened to bomb or invade those countries. The problem wasn’t the legality of the agreement – everything was absolutely legal – but rather Khrushchev’s mistaken political handling of the situation, when even though both Cuba and the USSR had the legitimate right, he started spinning theories about offensive and non-offensive weapons. In a political battle, you can’t afford to lose the high moral ground by employing ruses and lies and half-truths.

The revolutionary consciousness and organisation of the Cuban masses and their will and determination to resist aggression was, and continues to be, the decisive factor in the defence of the Cuban Revolution. This objective political fact kept intruding into the subjective actions of both the US and Soviet governments during the October crisis. For the Cuban revolutionaries, the economic, military and political ties forged with the Soviet Union had been an irreplaceable factor in their survival from the period after the January 1959 triumph of the revolution through the Playa Giron defeat of the US-organised mercenary invasion. Nevertheless, the unfolding of the Missile Crisis and its ultimate resolution left the Cuban leadership feeling vulnerable, insulted and bypassed by the perceived highhanded behaviour of the Soviet government led by Nikita Khrushchev.

In his January 25-26, 1968, speech, focused almost exclusively on the Missile Crisis and its lessons, Fidel Castro said, “I am sincerely convinced that the Soviet Party bears great responsibility in what happened and acted in a totally disloyal manner in its relations with us.”

Referring to the continuing terrorist attacks against Cuba that never stopped after Soviet missiles, planes and combat troops were removed from Cuba at the “end” of the October crisis, Castro stated:

Together with the pirate attacks and the U-2 flights, incidents began to flare up at the Guantanamo base [the military base on Guantanamo was ceded to the US government in the notorious neo-colonial Platt Amendment of 1901 passed by the US Congress and has been maintained to this day against the demands for its return to Cuban sovereignty]. The same Guantanamo base which, we are certain, would have been dismantled had there been a modicum of serenity and firmness during the October crisis. Had they had the presence of mind to have posed and demand correctly from a principled standpoint, had they said that they would withdraw the missiles if satisfactory guarantees were given to Cuba, had they let Cuba negotiate, the crisis might even have turned into a political victory… All the rest are euphemisms of different kinds: Cuba was saved, Cuba lives. But Cuba had been alive and Cuba had been living and Cuba did not want to live at the expense of humiliation or surrender; for that you do not have to be a revolutionary. Revolutionaries are not just concerned with living, but how one lives, living most of all with dignity, living with a cause, living for a cause… Cuba did not agree with the way the issue was handled; it stated the need to approach the problem from different, more drastic, more revolutionary and even more legal positions; and it totally disagreed with the way in which the situation was terminated.

‘Uncontrolled forces’

At the height of the crisis, the central Cuban leadership was certain that a full-scale invasion of the island was imminent. As shown above, preparations – “contingency plans” – for such an invasion had, for many months prior to the secret installation of the Soviet missiles, been in place. This was the only conceivable basis for Khrushchev to make the missile proposal to the Cuban leaders. In fact, a US invasion of Cuba was on the hair-trigger of being ordered on several concrete conjunctures in the course of the crisis.

The issue of carrying out a direct US assault was being furiously debated within the Kennedy administration and the narrow circle of bipartisan Congressional leadership that was privy to the deliberations at the top. As president and commander-in-chief, Kennedy had to choose whether to give the order to invade – again, everything was already in place for the execution of an invasion – the island where many nuclear warheads were already in place, targeting US territory and where Cuban armed resistance was certain to be massive, highly motivated, well-led and creative. The Cuban masses, having just experienced a profound social revolution, drawing the immense majority of the Cuban population into revolutionary struggle and consciousness, would be fighting from their own territory against a foreign invasion force and massive bombing assaults. Thousands of Cuban civilians would have been killed in these air strikes. The political consequences of this carnage – against a sovereign people with the gall to make a revolution, throw out a venal dictator, institute land reform, literacy campaigns, rent reduction and abolish Jim Crow-segregation – would certainly have been devastating for Washington even if nuclear warheads were never launched on either side, a dubious prospect at best. Washington would lose the “moral high ground” so crucial to concrete questions of world politics. Cuba would regain what had been eroded by the secretive, clumsy adventurism of Khrushchev’s “initiative” and its incompetent implementation.

The question of the nuclear weapons that were already on the island and the more that were en route would likely have been rendered secondary and the question of Cuba’s right to self-determination would have again risen to the fore. Kennedy was politically savvy enough to realise all of this and finally rebuffed the advocates of launching an invasion.

Uppermost in Kennedy’s considerations were the physical presence of thousands of Soviet combat troops and military personnel (there were some 40,000 Soviet mechanised combat troops in Cuba, although the Kennedy administration seems to have counted less than half the actual number). This fact posed the question that Soviet casualties would be inevitable, further sharply posing the question of questions … would the US invasion inexorably lead to nuclear exchanges? Who would fire first becomes almost a moot, secondary question in the framework of such a political confrontation.

US “intelligence” estimates were that 18,500 US casualties would take place in the first period after a US invasion, according to declassified material obtained by the National Security Archive. The presence of Soviet nuclear warheads and large numbers of Soviet military personnel, fighter jets, anti-aircraft gun emplacements and so on, was another major factor leading Kennedy to repeatedly postpone the invasion and opt for a naval blockade (labelled a “quarantine” for legalistic purposes) of Cuba and the drama of a relatively slow showdown unfolding over days in the Atlantic while negotiations between Washington and Moscow intensified, negotiations that excluded the Cuban government … as if Cuba had nothing to do with what was happening.

It is always the case when war and combat is actually joined that the “law of unintended consequences” would come into dynamic play. Or, as Frederick Engels, put it, “Those who unleash controlled forces, also unleash uncontrolled forces.”

The letters

On October 26, 1962, Fidel Castro – at the most intense, dangerous point of the entire crisis – wrote a letter to Nikita Khrushchev, which stated:

Given the analysis of the situation and the reports which have reached us, [I] consider an attack to be almost imminent – within the next 24 to 72 hours. There are two possible variants: the first and most probable one is an air attack against certain objectives with the limited aim of destroying them; the second and though less probable, still possible, is a full invasion. This would require a large force and is the most repugnant form of aggression, which might restrain them.

You can be sure that we will resist with determination, whatever the case. The Cuban people's morale is extremely high and the people will confront aggression heroically.

I would like to briefly express my own personal opinion.

If the second variant takes place and the imperialists invade Cuba with the aim of occupying it, the dangers of their aggressive policy are so great that after such an invasion the Soviet Union must never allow circumstances in which the imperialists could carry out a nuclear first strike against it.

I tell you this because I believe that the imperialists' aggressiveness makes them extremely dangerous and that if they manage to carry out an invasion of Cuba -- a brutal act in violation of universal and moral law – then that would be the moment to eliminate this danger forever, in an act of the most legitimate self-defense. However harsh and terrible the solution, there would be no other.

Khrushchev responded, in a second round of letters with Castro that:

In your cable of October 27 you proposed that we be the first to carry out a nuclear strike against the enemy's territory. Naturally you understand where that would lead us. It would not be a simple strike, but the start of a thermonuclear world war.

Dear Comrade Fidel Castro, I find your proposal to be wrong, even though I understand your reasons.

… As far as Cuba is concerned, it would be difficult to say even in general terms what this would have meant for them. In the first place, Cuba would have been burned in the fire of war...

Now, as a result of the measures taken, we reached the goal sought when we agreed with you to send the missiles to Cuba. We have wrested from the United States the commitment not to invade Cuba and not to permit their Latin American allies to do so. We have we wrested all this from them without a nuclear strike.

We consider that we must take advantage of all the possibilities to defend Cuba, strengthen its independence and sovereignty, defeat military aggression and prevent a nuclear world war in our time.

And we have accomplished that.

Of course, we made concessions, accepted a commitment, action according to the principle that a concession on one side is answered by a concession on the other side. The United States also made a concession. It made the commitment before all the world not to attack Cuba.

That's why when we compare aggression on the part of the United States and thermonuclear war with the commitment of a concession in exchange for concession, the upholding of the inviolability of the Republic of Cuba and the prevention of a world war, I think that the total outcome of this reckoning, of this comparison, is perfectly clear.

Castro then responded:

I realised when I wrote them that the words contained in my letter could be misinterpreted by you and that was what happened, perhaps because you didn't read them carefully, perhaps because of the translation, perhaps because I meant to say so much in too few lines. However, I didn't hesitate to do it…

We knew and do not presume that we ignored it, that we would have been annihilated, as you insinuate in your letter, in the event of nuclear war. However, that didn't prompt us to ask you to withdraw the missiles, that didn't prompt us to ask you to yield. Do you believe that we wanted that war? But how could we prevent it if the invasion finally took place? The fact is that this event was possible, that imperialism was obstructing every solution and that its demands were, from our point of view, impossible for the USSR and Cuba to accept.

And if war had broken out, what could we do with the insane people who unleashed the war? You yourself have said that under current conditions such a war would inevitably have escalated quickly into a nuclear war.

I understand that once aggression is unleashed, one shouldn't concede to the aggressor the privilege of deciding, moreover, when to use nuclear weapons. The destructive power of this weaponry is so great and the speed of its delivery so great that the aggressor would have a considerable initial advantage.

And I did not suggest to you, Comrade Khrushchev, that the USSR should be the aggressor, because that would be more than incorrect, it would be immoral and contemptible on my part. But from the instant the imperialists attack Cuba and while there are Soviet armed forces stationed in Cuba to help in our defense in case of an attack from abroad, the imperialists would by this act become aggressors against Cuba and against the USSR and we would respond with a strike that would annihilate them.

Everyone has his own opinions and I maintain mine about the dangerousness of the aggressive circles in the Pentagon and their preference for a preventive strike. I did not suggest, Comrade Khrushchev, that in the midst of this crisis the Soviet Union should attack, which is what your letter seems to say; rather, that following an imperialist attack, the USSR should act without vacillation and should never make the mistake of allowing circumstances to develop in which the enemy makes the first nuclear strike against the USSR. And in this sense, Comrade Khrushchev, I maintain my point of view, because I understand it to be a true and just evaluation of a specific situation. You may be able to convince me that I am wrong, but you can't tell me that I am wrong without convincing me.

In the January 25-26 speech, Castro explains his thinking as he drafted his first letter to Khrushchev “with the utmost care and scruples because what I was about to say was so audacious and daring that I had to present it well”. He continued:

And there I was thinking, well, what could be done?… Of course we could never present our country as the aggressor or anything like that, but my opinion was that if they invaded we would have to open fire on them with a complete and total round of nuclear rockets. With the total conviction that in a situation such as that, whoever struck first would have a 99 percent advantage. It would not have been a surprise attack, but only in the case of a concrete invasion, which would have involved the Soviet troops stationed here and, since they would not have just stood by and watched them die here, what would they have waited for to settle the problem.

(In fact, any advantage from such a strike would be quickly overwhelmed by the devastation from the inexorable waves of second, third and many strikes that would be unleashed. Would Kennedy, unable to resist launching the invasion, have resisted a massive and devastating retaliation on Soviet targets, after nuclear weapons had been dropped on invading US troops? By then all Hell, literally, would have broken loose.)

Castro’s exchange of letters with Khrushchev assumes that given the forces in motion – 300,000 Cuban combatants, 40,000 Soviet military personnel confronting a US invasion force projected to quickly reach hundreds of thousands, while massive US air strikes and countering Cuban-Soviet anti-aircraft fire, enormous naval forces, many armed with nuclear weapons, including torpedoes – that the US invasion, which he considered inevitable and imminent, would inexorably go nuclear. Following this undoubtedly correct assumption, Castro’s logic and formulations in his initial letters becomes necessarily more abstract and algebraic. He presents, in the rush and incredible heat and speed of events, a post-invasion scenario where Soviet forces could strike, in a limited “tactical” use (although those terms are not specifically used), the US forces before the US could strike the Soviet forces. The same technical, military logic of “pre-emption” would, of course, dominate the US side which had a clear superiority in both quantity and quality of nuclear weapons deliverance at that point, the full extent of which the Cuban leadership was not likely aware of the extent of.

Castro continued, “Keep in mind that back then there was not the unlimited supply of rockets that there is today. The Americans did not have too many rockets then and we knew the speed of their planes and those things.” (In reality, the US supply of rockets was quite sufficient to destroy not only Cuba, but virtually all human life on the Earth.)

The MAD doctrine was based on each side’s nuclear arsenal countermanding the others. The seemingly absurd stockpiling of nuclear warheads and delivery system locations had the “rational” kernel of logic that after a “first strike” or pre-emptive launch of warheads the “other side” would still have enough of an atomic arsenal left to deliver a crushing response. The idea, developed by “Dr. Strangelove” US theorists like Herman Kahn and accepted by their Soviet equivalents, was to build up and protect a “second strike” capacity in order to obviate a “first strike”. Of course, Washington continued – and continues to this day – to develop a “decisive” first-strike capability, largely through anti-ballistic and “Star Wars” systems to intercept and eliminate the other sides’ “second strike” (or first, or any strike) giving the US a credible “first strike”.

The fact that a US invasion – that is, its actual occurrence – of Cuba would have set in motion a dynamic that would have rendered moot, useless and ridiculous the question of who would “fire” the “first” nuclear weapon, if that could even be determined after the event (if indeed the word after would have any content). Dozens of ships, planes and launch sites were on the ground, under the control of dozens of military officers subject to “orders” in what would have been unimaginable chaos and breakdown inevitable in what would have been the first nuclear exchange in world history. Would anyone have even known who struck first? The key point – the only determinant fact – in whether nuclear holocaust would be unleashed was whether the US would invade Cuba.

New facts

What is now known about the Missile Crisis is that a situation existed where, at the height of the confrontation, from October 25-28, literally dozens of military officers well below the executive political “decision makers” in a theoretical chain of command, on both the Soviet and US side, had the capacity and even the authority to push the nuclear button and pull the nuclear trigger. We certainly know this to be true in the first-hand accounts by Soviet and US military officers and personnel on the ground, on the oceans and in the air that have become public and from “classified” government documents on both sides (see Noam Chomsky’s “Cuban Missile Crisis: How the US Played Russian Roulette with Nuclear War”, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/oct/15/cuban-missile-crisis-russian-roulette) in the October 15 Guardian newspaper, which cites several harrowing moments of near disaster.)

Michael Dobbs in an October 18, 2012, New York Times op-ed piece (“The Price of a 50-Year Old Myth”) wrote, “While the risk of war in October 1962 was very high (Kennedy estimated it variously at between 1 in 5 and 1 in 2), it was not caused by a clash of wills. The real dangers arose from ‘the fog of war’. As the two superpowers geared up for a nuclear war, the chances of something going terribly wrong increased exponentially… By Saturday, Oct. 27, the two leaders were no longer in full control of their gigantic military machines, which were moving forward under their own momentum. Soviet troops on Cuba targeted Guantánamo with tactical nuclear weapons and shot down an American U-2 spy plane. Another U-2, on a ‘routine’ air sampling mission to the North Pole, got lost over the Soviet Union. The Soviets sent MiG fighters into the air to try to shoot down the American intruder and in response, Alaska Air Defense Command scrambled F-102 interceptors armed with tactical nuclear missiles. In the Caribbean, a frazzled Soviet submarine commander was dissuaded by his subordinates from using his nuclear torpedo against American destroyers that were trying to force him to the surface.”

In his Guardian piece cited above, Chomsky, referring to the famous (to some detractors, infamous) October 26 letter of Fidel Castro, states:

As this was happening and Washington was debating and Kennedy poised to decide on a US invasion, Fidel Castro wrote a letter to Nikita Khrushchev which has been interpreted, over Castro’s sharp objection, as advocating a Soviet nuclear attack – a so-called ‘first strike’ against US territory if the US invasion were to actually occur. Khrushchev himself took the necessarily and purposely algebraic and highly cautious words of Castro as such a call and used Castro’s wording as practically a cover to carry out the retreat and concessions to Kennedy that diffused the crisis and reverse the momentum towards purposeful or accidental nuclear exchanges.

Extraordinary gathering

Details on the Cuban leadership’s viewpoint on the origins, development and “end game” of the October crisis and their attitude to the actions and behaviour of the Soviet leadership, were presented on January 25-26, 1968, cited above, when Fidel Castro gave an exhaustive 12-hour speech to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC). In a remarkable oration spread over two days, Castro painstakingly – combining great emotion with razor sharp, cool logic – detailed how the “Missile Crisis” unfolded and how Cuba’s relations with the Soviet Union emerged out of the crisis different from what they had been before. The January 24-26, 1968, Central Committee meeting was perhaps the nadir of the downward spiral of Cuban-Soviet relations set in motion by the October crisis of 1962. (The entire speech, previously unpublished in any public medium, was printed in 2002, for the first time, in the official Cuban Council of State English translation, in the book Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba’s Struggle with the Superpowers after the Missile Crisis by James Blight and Philip Brenner, published by Bowman and Littlefield.)

The timing of the special, extraordinary meeting of the PCC Central Committee was not fortuitous. It was held just 107 days after the death of Che Guevara and the defeat of his guerrilla forces based in Bolivia, which was a real blow to the Cuban revolutionaries and would raise many challenges in the development of Cuba’s revolutionary foreign policy in a new objective reality. (This question will be returned to in detail in the next article in this series.)

Fidel Castro and the Cuban leadership placed an important part of the responsibility for the defeat of Che’s guerrillas on the top leadership of the Bolivian Communist Party, which supported the program and perspective of the Soviet Union in Latin America and opposed Che Guevara’s armed struggle and leadership in Bolivia (which was seen as the initial base for a continental revolutionary movement), reneging on previously given commitments. The Cuban revolutionary line in Latin America was opposed – with varying degrees of vehemence – by virtually all of the Latin American Communist parties. This betrayal disrupted and undermined the formation and development of urban resistance forces crucial to supplement Che’s struggle, leaving the guerrillas exposed and vulnerable.

At the time of their April 1961 victory at the Bay of Pigs over the US-organised Cuban counter-revolutionaries, Fidel Castro declared that the Cuban Revolution was a socialist revolution and that he was a “Marxist-Leninist”. Castro’s words wholly corresponded to the social and economic deeds of his revolutionary government and to the profound internationalism of the Cuban leadership team (see the second part of this series at http://links.org.au/node/2961).

The Cuban revolutionaries shared this terminology with the government of the Soviet Union (and the Chinese government as well, which was then engaged in a war of words with the Soviet leadership), but the Castro leadership team’s domestic policies and revolutionary internationalist foreign policy perspective stood in unspoken contrast to the outlook and program of the Soviet government and Communist Party, particularly in regard to the “road to socialism” in Latin America and other semi-colonial countries, and the promotion of “détente” and “peaceful coexistence” with the advanced capitalist-imperialist powers. Prior to the Missile Crisis these differences were subsumed in the alliance that was forged between the revolutionary government of Cuba and the Soviet Union and its allied Eastern European governments.

Prior to Fidel Castro’s speech, the Central Committee gathering had heard an extensive report by Raul Castro, the chair of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (Raul Castro is Cuba’s president today). The report was a damning indictment of a secret faction of the PCC led by Anibal Escalante.

Escalante

Escalante’s faction was composed of former leaders, like himself, and cadres of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP). Before the revolution the PSP, which had a base in the industrial working class and trade unions, was connected to the dominant currents in the “world Communist movement” and Latin American Communist parties that looked to the Soviet Union for political direction and program. The PSP initially opposed the July 26 Movement led by Fidel Castro, coming out in support and joint activity only in the last period before the revolutionary triumph. Over the next few years the majority of PSP cadres were successfully integrated into what became the PCC. In 1962 Escalante, who had been the top functionary of the Integrated Revolutionary Organisation, an initial formation bringing together the currents supporting the revolution, had come under fierce public criticism by Fidel Castro for “sectarianism” and “bureaucratism” in March 1962 (http://www.walterlippmann.com/fc-03-26-1962.html).

(Some 35 members of the so-called “microfaction” were expelled from the PCC and received prison sentences from two to 15 years. The most serious of the charges involved secret activity aimed at forging ties between the “microfaction” and officials and Communist Party leaders in the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and Czechoslovakia in their common opposition to the revolutionary line of the PCC in Latin America and the position of the large majority of the PCC in domestic and foreign policies in general, going so far as to urge Soviet economic pressure on Cuba, for which they were charged with treason. Escalante’s grouping never argued for their political positions openly within the structures and procedures of the PCC, which was their right. In their secret functioning inside Cuba and intrigues with Soviet and Eastern European officials and diplomats, they portrayed Che Guevara as “Trotskyite adventurer” and the Castro leadership as “petty bourgeois” elements that seized control of the revolution, holding the working class in contempt. Moreover, the Cuban revolutionary leadership was “anti-Soviet” and did not support Soviet “hegemony”.)

The political lessons drawn by the revolutionary leadership in Cuba from the perceived Soviet “capitulation” to Washington were sharp and clear: they felt they were now and always would be in the final analysis “on their own”. Or, more precisely, that the survival and security of the Cuban Revolution would ultimately be dependent not on powerful benefactors – who would no longer be prettied up in their minds to be more revolutionary than they actually were – but, rather, through the extension of the revolution, especially across the Americas.

In fact, following the resolution of the Missile Crisis – which was hugely traumatic in world public opinion – led to increased propaganda for “peace” and “reconciliation” in both Moscow and Washington, with accompanying diplomatic manoeuvring. This culminated in the signing by the governments of the United States, United Kingdom and the Soviet Union of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (formally the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which was strongly welcomed in world public opinion when it went into effect in October 1963, one year to the month from the political drama and trauma of the Missile Crisis. The treaty did not ban “underground” nuclear tests, which could also lead to radioactive releases into the atmosphere as well ground water. The treaty put no limits on the production of nuclear warheads and their fitting onto missiles.)

The aftermath of the Missile Crisis was that Soviet-Cuban relations over the next six years politically deteriorated to nearly a bitter, breaking point. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963 and Khrushchev’s leadership in the Soviet Communist Party and Soviet state came to an ignominious end as he was pensioned off and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev and Alexi Kosygin In October 1964. The new Lyndon B. Johnson White House abided by Kennedy’s verbal “pledge” and invasion plans were put in mothballs, although covert action, terrorism and containment continued. Primary focus and attention shifted to Indochina where Johnson maintained continuity with Kennedy’s intervention and deepened it.

Resolution?

The immediate threat of an US-Soviet nuclear exchange and war receded on October 28 with the announcement that Soviet ships had stopped advancing and that Soviet missiles would be withdrawn. But for Cuba the crisis and the pressure intensified.

Not even two weeks after the supposed resolution of the crisis and the world’s “sigh of relief”, 400 Cuban workers were killed when a Cuban counter-revolutionary sabotage team dispatched from the US blew up a Cuban industrial facility. Right up until his assassination Kennedy was approving terrorist attacks against Cuba. US intervention by proxy never stopped and became systematic. US-backed counter-revolutionaries were defeated in the Escambray mountains in central Cuba in a campaign from 1963-65.

The six years that followed the end of the Missile Crisis saw Cuban-Soviet relations decline – in public as well as “private” state-to-state and party-to-party behind-the-scenes relations – almost to a breaking point, before formal and definite improvements after 1968 through the 1970s and 1980s until the Soviet government collapsed in 1991, setting off a huge economic depression and crisis in Cuba. (In this period of improved relations, fundamental contradictions remained and sharp policy differences emerged over questions like Soviet policies in Africa, military tactics in Angola and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which Cuba opposed. These questions will be returned to in future parts of this series.)

As this article gets ready to be launched into cyberspace, I came across an October 22, 2012, article written for the Cuban press by Fidel Castro. The article is entitled “Fidel Castro is dying” and is written tongue-in-cheek in response to the ridiculous and repulsive rumour-mongering – yes, this time he really is dying even dead, we’ve got a Venezuelan doctor who knows for sure this time – periodically engaged in by professional Castro haters. It is a veritable cottage industry. Fidel, with pictures, once again, combats the liars and the fools:

While many persons in the world are deceived by information agencies which publish this nonsense – almost all in the hands of the privileged and rich – people believe less and less in them. Nobody likes to be deceived; even the most incorrigible liar expects to be told the truth. In April of 1961, everyone believed the information published in the news agencies that the mercenary invaders of Girón or Bay of Pigs, whatever one wants to call it, were approaching Havana, when in fact some of them were fruitlessly trying by boat to reach the yanqui warships escorting them.

The peoples are learning and resistance is growing, faced with the crisis of capitalism which is recurring with greater frequency; no lies, repression or new weapons will be able to prevent the collapse of a production system which is increasingly unequal and unjust.

A few days ago, very close to the 50th anniversary of the October Crisis, news agencies pointed to three guilty parties: Kennedy, having recently become the leader of the empire, Khrushchev and Castro. Cuba did not have anything to do with nuclear weapons, nor with the unnecessary slaughter of Hiroshima and Nagasaki perpetrated by the president of the United States, Harry S. Truman, thus establishing the tyranny of nuclear weapons. Cuba was defending its right to independence and social justice.

When we accepted Soviet aid in weapons, oil, foodstuffs and other resources, it was to defend ourselves from yanqui plans to invade our homeland, subjected to a dirty and bloody war which that capitalist country imposed on us from the very first months, which left thousands of Cubans dead and maimed.

When Khrushchev proposed the installation here of medium range missiles similar to those the United States had in Turkey – far closer to the USSR than Cuba to the United States – as a solidarity necessity, Cuba did not hesitate to agree to such a risk. Our conduct was ethically irreproachable. We will never apologize to anyone for what we did. The fact is that half a century has gone by and here we still are with our heads held high.

[Ike Nahem is a long-time anti-war, labour and socialist activist. He is the coordinator of Cuba Solidarity New York (cubasolidarityny@mindspring.com) and a founder of the New York-New Jersey July 26 Coalition. Nahem is an Amtrak Locomotive Engineer and member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, a division of the Teamsters Union. These are his personal political opinions. Comments and criticisms can be sent to ikenahem@mindspring.com.]