The problem of relative privilege in the working class

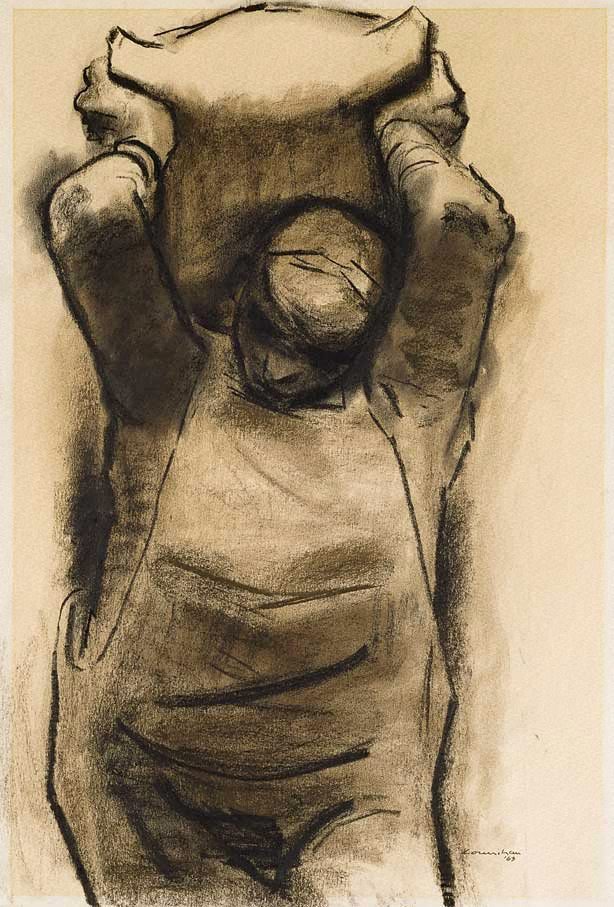

"Waterside worker', by Noel Counihan, 1963.

By Chris Slee

March 18, 2013 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – In his article entitled “Is there a labour aristocracy in Australia?” (published in the Socialist Alternative magazine, Marxist Left Review) Tom Bramble criticises the concept of the “labour aristocracy” on a number of grounds.

He says that the term “labour aristocracy” is ambiguous. Pointing out that different people have used it in different ways, he asks who is included: “Is it the union bureaucracy and the parliamentarians? Plus the skilled tradesmen? Or, indeed, is it the entire Western working classes?”[1]

The most common use of the term “labour aristocracy” is to refer to skilled workers in the imperialist countries, who are considered to have been bought off with a share of imperialist super-profits. Bramble argues that this theory does not explain the actual differences in political outlook among different groups of workers – skilled workers are not necessarily more conservative than unskilled ones.

He adds that the theory of labour aristocracy “exaggerates divisions within the working class and underestimates the potential for working class unity against the capitalist class”.[2]

I myself don’t much like the term “labour aristocracy”. I prefer to talk about “relative privilege”. There are many different forms of inequality within the working class. The term “labour aristocracy” seems inadequate to cover them all.

However, I think it is important to recognise that inequality within the working class exists, and that it can have a big impact on workers’ political outlook. The better-off sections will often defend their relative privileges at the expense of other workers (though this is not inevitable).

Inequality among workers

Capitalism develops unevenly, and produces very different wages and conditions for different sections of the working class.

The most obvious example is that average pay rates for workers in the advanced capitalist countries are many times higher than average pay rates for workers in less developed countries.

There are also differences within countries. As a general rule, skilled workers are paid more than unskilled workers. But there are many other differences:

- Workers in predominantly male occupations tend to be paid more than workers in predominantly female occupations.

- Workers with permanent full-time jobs are better off than those with casual or part-time jobs. In many Third World countries, permanent workers are a small minority of the population, with the majority of workers being in the “informal sector”, trying to survive on poorly paid casual work.

- In the Australian Public Service, there is a formal hierarchy with multiple levels. The bottom rung of the ladder is called “APS 1” (Australian Public Service, level 1). It goes up to APS 6, then the terminology changes to EL 1 (Executive Level 1) and EL 2, then above that there are various levels of the Senior Executive Service. To add to the complexity, with the introduction of agency bargaining in the Australian Public Service about 20 years ago, the pay rates in different government departments began to diverge. An APS 3 in the Australian Taxation Office is paid differently to an APS 3 in Centrelink.

- Workers in the mining industry in Australia are currently paid much more than those in most other industries (though their working conditions are very bad, and they could lose their jobs when the mining boom goes bust).

- In China, workers with urban residency status are much better off than workers whose official status is “rural”, but who work in urban factories.

Inequality, conflict and solidarity

Material inequalities between different groups of workers can contribute to conflict between them. Often one group of workers will try to defend their position of relative privilege against other workers who are perceived as threatening it.

For example, the relatively privileged position of Australian workers compared to those in many other countries affects attitudes towards immigration. Many workers in Australia fear that migrants from poor countries will work for lower rates of pay, and will therefore take jobs from Australian workers and/or cause Australian pay rates to fall.

This was a contributing factor to working-class support for the White Australia policy in the past, and still affects attitudes to immigration and refugees today. It helps to explain the high level of hostility toward refugees arriving in Australia by boat. (Of course, this hostility is greatly exacerbated by politicians and the media, who deliberately set out to create fears about “boat people”.)

While recognising that inequality provides an objective basis for potential conflict among groups of workers, we should not view this as an absolute and unchangeable obstacle to working-class unity. There is often a political struggle within the relatively privileged sections of the working class about how to respond. Those defending the maintenance of privilege may be challenged by those promoting solidarity.

In the early 20th century, many Australian unions supported the White Australia policy. But the Industrial Workers of the World opposed the policy and tried to organise non-white workers as well as white workers.

The IWW was crushed by state repression during the First World War. But in subsequent years Australian unions have at times taken action in solidarity with workers overseas, with national liberation struggles and with Aboriginal people.

Similarly there have been debates within the unions about equality for women. For a long time the tramways union banned women from becoming tram drivers in Melbourne. In 1956 the union went on strike to oppose management’s plans to train female drivers. In 1973 the union imposed a ban on the route where training of female drivers was occurring. After a long campaign, the ban on women drivers was overturned by a vote of union members in 1975.[3]

Origins of inequality among workers

What are the reasons for inequality amongst different groups of workers?

Tom Bramble criticises the idea that the labour aristocracy gets a “bribe” from the capitalists, paid for out of imperialist super-profits. He says that skilled workers are paid more than other workers because their labour power is worth more.

He attributes the higher wages in advanced capitalist countries to higher productivity:

More generally, the notion that higher wages in the developed countries derive from low wages in the less developed, a central proposition of [Arghiri] Emmanuel’s version of unequal exchange, overlooks the fact that while wages may be higher in the former, the rate of exploitation – the proportion of the value created by the worker appropriated by the capitalist – is also higher. This apparent paradox can be explained by the fact that technique of production, and thus productivity, is usually far greater. Higher wages in the developed countries simply reflect the much higher value of labour power owing to the skills, training and cultural development of workers in such countries.[4]

But why does labour productivity differ so markedly from one country to another? In particular, why is the productivity of labour generally higher in imperialist countries than in Third World countries?

The reasons are complex. Part of the answer is that some of the wealth plundered from colonies was invested in the colonising powers, resulting in the development of the productive forces, and of labour productivity, in these countries.

For a long time the most advanced factories were built in the imperialist countries. In the 19th century, textile mills were built in England rather than India. In the 20th century, car factories were initially built in the United States, Europe and Japan, rather than Africa, Latin America or most of Asia.

In this situation, workers in the imperialist countries were able to win some gains in pay and conditions as a result of their trade union struggles. Because of the high productivity of labour, the capitalists were able to grant pay rises without affecting their profits too drastically (though usually they still had to be forced to do so).

In addition capitalist governments, aiming to alleviate discontent among their working class, ensure social peace and promote loyalty to the nation state, introduced some welfare measures (to varying degrees in different imperialist countries).

The outcome was a vast gulf between the pay, conditions and welfare rights of workers in imperialist countries and those in colonial or semi-colonial countries. The relative privilege of workers in the imperialist countries has been the material basis for working-class support for a range of racist and exclusionary policies, including the White Australia policy in the past and continuing anti-refugee policies in Australia today, the “Fortress Europe” policy and the attempts to restrict Latin American immigration to the United States.

This is not to say that racist attitudes will inevitably predominate among workers in imperialist countries. Sentiments of solidarity also exist, and can be further developed by good leadership. But it will remain a very difficult struggle so long as global economic differences remain as large as they presently are.

Changes in the location of industry

In recent years some high-technology industries have shifted to Third World countries, such as South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and more recently China.

In part, this is because technology makes it easier to organise production on a global scale. It has become easier to close down a factory in one country and replace it with a factory in another country.

A range of factors may influence decisions on the location of production, including closeness to markets, perceptions of political stability, the quality of infrastructure, and the availability of workers with necessary skills. But labour costs are a very important factor. Other things being equal, capitalists will locate their factories where pay rates are lower.

The shifting of some production to Third World countries (or the threat to do so) has weakened the bargaining position of unions in imperialist countries. This has contributed to the gradual decline of pay and conditions in these countries.

On the other hand, there has been a growth in workers’ struggles in some of the countries to which production has been shifted. For example, there have been many strikes in China in recent years, and Chinese workers have won substantial pay rises.

Nevertheless, Chinese pay rates remain far below those in the imperialist countries. Thus there is still an incentive for capitalists to shift production from these countries to China.

It is not just factory work that is being relocated. A lot of call-centre work has been relocated from Australia to India and the Philippines.

Union response

How should unions in the advanced capitalist countries respond to this situation?

The traditional response of Australian unions has been to call for increased tariff protection, or for subsidies to companies investing in Australia. Neither of these is a good solution from a socialist point of view.

A better approach is to try to assist workers in countries such as China to improve their pay and conditions. There have been campaigns to shame companies such as Apple over its treatment of workers in the Chinese factories that make its products.

Such campaigns have had a degree of success in some cases. It is hard to judge how big an impact they have had, because transnational corporations often operate through subcontractors, and it is hard to check on what is happening in all the factories.

In any case, monitoring by foreign NGOs is no substitute for the organisation of the Chinese working class in strong trade unions. Despite the militancy of many Chinese workers, the official trade union movement in China is very conservative and does not support strikes.

How should Australian unions react when companies threaten to close a factory in Australia and move production to another country (whether a Third World or another imperialist country)?

We should argue that it is the responsibility of the Australian government to ensure that there are jobs with good pay and conditions for all workers in Australia. This means the government should take over factories threatened with closure and run them as public enterprises, or else provide the sacked workers with alternative work. Public housing, public transport and renewable energy are some of the areas that governments should invest in and create jobs.

In support of these demands we should encourage pickets, factory occupations, street demonstrations, etc.

‘Guest workers’

Another issue is the use of “guest workers” (in Australia, workers on 457 visas). In this case, instead of shifting production to a country where pay rates are lower (which is not possible for some kinds of work, e.g. mining and construction), workers from poorer countries are brought in temporarily to work in a rich country on lower pay and conditions than those prevailing in the rich country.

How should we respond?

We should campaign for the abolition of the “guest worker” (457 visa) system, and demand that all people coming to work in Australia are entitled to permanent residency and eventual citizenship. Existing 457 visa workers should be offered permanent residency.

Unions should recruit the 457 visa workers, and ensure that they receive the same pay and conditions as Australian workers. This has been done in some cases.

Employer violations of 457 visa rules

Companies are only supposed to use workers on 457 visas if workers with the relevant skills are not available in Australia. In reality, companies frequently disregard this requirement. Unions have tried to limit the number of guest workers by ensuring that companies abide by the regulations, and have called for the law to be made stricter and enforced more rigorously.

Recently there was a picket in Werribee, an outer suburb of Melbourne, around this issue. Workers on 457 visas were being used on a construction project. Unemployed workers with relevant skills living in the Werribee area set up a picket demanding that they be given jobs on the site. The picket eventually dispersed after the police threatened to physically attack it.[5]

It may seem reasonable to demand that companies abide by the legal limits on the use of 457 visas. However this can create problems if the guest workers are already in Australia, because it may lead to them being sacked and sent home.

If employers have brought guest workers to Australia contrary to the guidelines, unions face a dual task. On the one hand they should try to recruit the guest workers to the union and defend their pay and conditions. But unions also have to support their unemployed members who missed out on jobs because of the employer’s actions. How to combine these two tasks is not easy.

One approach might be to demand that local workers be employed in addition to the 457 visa workers. The additional cost of employing two sets of workers would be a deterrent to employers who try to break the rules.

If the company decides to sack the guest workers and send them home, we should oppose this. If they are nevertheless sacked, we should demand that they receive redundancy payments equivalent to what they would have been paid if they had worked the expected length of their employment.

Conclusion

Such situations arise because of the highly unequal pay rates of workers in different parts of the world, which makes it worthwhile for bosses to either shift the work to another country, or move workers between countries.

One of our long-term goals should be to reduce inequality between workers in different countries, by raising the living standards of those in poorer countries. Pay rates should be leveled up, not leveled down as the capitalists would like.

Some gains can be made through successful struggles by unions and other social movements in Third World countries. Even bigger gains can be made through the coming to power of socialist governments, which can use their countries’ resources for the benefit of the majority of people, rather than local and foreign capitalists.

People in the imperialist countries should do what they can to help these unions, social movements and socialist governments in Third World countries.

But radical change is needed in imperialist countries too. A socialist government coming to power in an advanced capitalist country could give a great deal of aid to help develop the productive forces of poorer countries, enabling them to raise the living standards of their people.

The struggle between solidarity and the defence of relative privilege is part of the struggle for a socialist world.

[Chris Slee is a Socialist Alliance activist in Melbourne.]

Notes

- Bramble, Tom, Is there a labour aristocracy in Australia? Marxist Left Review, no. 4, winter 2012, p. 107

- Bramble, MLR, no. 4, p. 103

- See www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/barry.htm and www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/hindsight/cap-234074/4208670.

- Bramble, MLR, no. 4, p. 107.

- See www.greenleft.org.au/node/53367 and www.greenleft.org.au/node/53274.

Abolish citizenship?

Great article. I think it raises very good points, and none of the following is meant as a criticism of the points being made, but instead to add my own thoughts as I was reading the article. Something I have been thinking about when it comes to debates over immigration is should there be a push to reform the system that allows more people to become citizens, or should we push for the entire system of citizenship to be abolished? Why do we limit legal rights to citizens of a certain country? I think that all workers of the world should be treated with the same level of high respect and dignity, including access to food, shelter, self-development and meaningful work. I think that by limiting any demands to citizens only, yet loosening the restrictions to becoming a citizen invariably butts up against the us vs them mentality of base nationalism.

Chris writes: "Many workers in Australia fear that migrants from poor countries will work for lower rates of pay, and will therefore take jobs from Australian workers and/or cause Australian pay rates to fall."

I don't think that's a fear, that is a reality brought about by the capitalist system of competition. I think that a simple redirection of this anger towards those actually perpetrating the crime (the capitalists) is a solid tactic that I don't see often used. It's more difficult to make the case of solidarity if you accept the already slanted rules of the capitalist game. Much better to go straight to to the problem and attack it at it's root. Of course, how to do it is the question. I don't think that the government (definitely not in the US) is going to nationalize an industry when a factory shuts down. Even if they did, they could easily reverse this decision once public pressure has died down. I think that this factory takeover must be done by the workers of that factory and the workers of the community. If you could get the government to appropriate the factory and give ownership to that group, not as individual stakeholders, but as a class, that would really be something. Then you wouldn't likely see it taken away. After all, it would be the government taking our factory and giving it to others, as opposed to the government taking their factory and giving it to a capitalist.

Some points on an excellent article re: privilege

Excellent article, particularly its discussion of imperialism and the development of production, labor gains, and welfare states in the global north. There are some things I would like to comment on, either to expand on or to praise:

"Workers in predominantly male occupations tend to be paid more than workers in predominantly female occupations."

This is true, but it is an incomplete picture that should be expanded. While part of the pay gap is absolutely discrimination, another part is that male occupations include almost (prostitution being a notable exception) every single one of the most dangerous and deadly industries (which come with hazard pay), and men tend to choose to work longer hours and take less time off for domestic home-making labor (which is unpaid and mostly done by women), leading to greater promotion and to opportunities in more demanding, higher-paying industries. Note this:

"Workers in the mining industry in Australia are currently paid much more than those in most other industries (though their working conditions are very bad, and they could lose their jobs when the mining boom goes bust)."

One of the reason these male-dominated rural extractive industries pay so well is because they're dangerous as hell. People demand hazard pay to claw into the bowels of the Earth, shake hands with the devil, and bring up bits of shiny metal and flammable rock for industrial use, risking lung diseases, cave-ins, morlocks, and all other sort of nastiness.

On the other hand, these choices don't exist in a vacuum. This gendered division of labor is driven by social pressure put on both men and women to fulfill certain gender roles, and shaming, harassment, and worse for breaking those gender roles. So, obviously, more action to fight the gender binary is necessary. I'm not so much disagreeing with the 'men get paid more' point as trying to expand on it and put it in its broader social context.

"In China, workers with urban residency status are much better off than workers whose official status is “rural”, but who work in urban factories."

I'm glad this was brought up. It's very rare that any attention is paid to the differences between urban and rural people in either the developing or developed world. I know that even in my own country, the access to jobs, health care, communications technology, culture and arts, and political organization is much greater for those living in the city than those living in the country- and the gap is greater in developing countries. I think that bias and stereotypes against rural people is also something that the Left should discuss more often.

"A better approach is to try to assist workers in countries such as China to improve their pay and conditions. There have been campaigns to shame companies such as Apple over its treatment of workers in the Chinese factories that make its products."

This. So much of this. I have had enough of developed world union trying to maintain protectionist policies denied to the global south. We should be standing in solidarity (not charity) with the developing world's workers, lending our support to their labor and community struggles. I think it is important, not just to target individual companies, but to fiercely target organizations like the IMF and World Bank which set forth a program of 'complementary development', encourage the race to the bottom, and work to strike down developing-world tariffs, labor rights, environmental protection, and sovereignty.

The labour aristocracy and politics in the worker movement

Chris Slee’s article addresses important problems of stratification among workers and revolutionaries’ tactics towards these. But it addresses neither the significance of Tom Bramble’s rejection of the theory of the labour aristocracy—instead, he tends to agree with Bramble’s claim that the theory “underestimates the potential for working class unity against the capitalist class”—nor the significance of the theory for Marxism. In response I offer a brief sketch (Bramble’s article needs, and, indeed, deserves, a thorough critique, which is to come).

In Marxism, the theory of the labour aristocracy is perhaps best expressed in the development of Lenin’s political thought.

Lars Lih has explained how the narrative of a merger between the worker movement and socialism was a key party-building concept for Lenin throughout his life. It can be found in What Is to Be Done? and in Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder.

Yet Lenin’s thinking did not remain completely unchanged (to this extent I disagree with Lih). In 1914, what the German Social Democrats had become showed it was no longer the exemplar of the party he wanted.

Lenin set out to understand the political consequences of the emergence of imperialism, or monopoly capitalism. His chief conclusion was that the superprofits of monopolising capitals provided the basis for sustained concessions to, and the resultant relative privilege of, a stratum of workers (the ‘labour aristocracy’). Among at least some of these workers, opportunism —a willingness to sacrifice the historic and general interests of the working class to their alliance with ‘their’ capitalists (their relationship of concessions and relative privilege) —and a ‘bourgeois labour party’, in one form or another, was inevitable.

Thus, in the past, opportunists could be included in the revolutionary party, because the expectation was that they would in good time cease to be opportunists, but now opportunists must be excluded from the revolutionary party. Revolutionaries should not orient toward the existing opportunist ‘mass’ organisations, but toward merger with the mass of workers, and working people generally, who would continue to need and to listen to the socialists. In any case, in the class struggle, a part of the relatively privileged workers, who were, after all, still workers, would also be part of the revolutionary movement: the proportion would only be determined in the course of the class struggle.

In the early Comintern, Lenin and others tried to enact this concept for the formation of revolutionary parties. No-one was to be excluded except the opportunists. One aspect of this was the effort to include the ‘centrists’, so long as they would exclude the opportunists. In the case of Italy, this meant the forces led by Serrati, which were the majority in the Socialist Party and would have begun as a majority in the Communist Party, but he didn’t agree. (In 1924, when Antonio Gramsci had broken from the sectarian policy of Amadeo Bordiga to lead the Italian communist, he identified the creation of ‘the higher stratum, the labour aristocracy,’ as the particular determinant for the revolutionary party of ‘a strategy and tactics more complex and long-term’ than those seen in Russia in 1917.)

Today, we still live under the impact of imperialism and its political consequences. This is why I believe that SYRIZA suggests much about what is needed to work toward building a revolutionary party. However, this does not mean I agree with Louis Proyect when he writes:

I see SYRIZA as a throwback to the parties of the Second International in which left and right wings vied with each other. That includes the Russian Social Democratic Party that was home to a Bolshevik and Menshevik faction. It was a huge mistake for the Comintern to create a new kind of party that was purged of the reformist elements since the net result was division in the working class. Marxist parties have to engage with different levels of consciousness in the working class. When you amputate your right arm because it offends you, you lose contact with the masses who have not reached revolutionary conclusions. (http://louisproyect.wordpress.com/2013/03/13/greek-anarchists-and-greek…

First, SYRIZA is ‘purged’ of at least some ‘reformist’ elements—that is, those represented by PASOK and DIMAR. It is a ‘broad’ party, but still it is not as broad as the parties of the pre-WWI Second International, which included every trend in the worker movement. Of course, this has only created the possibility of SYRIZA acting differently. The centrist leadership(s?) in SYRIZA might keep the Greek worker movement from struggling for socialism; the revolutionary leadership(s?) might through its action in SYRIZA (at least for now) start win the worker movement toward a struggle for socialism.

Second, the Comintern’s efforts did not create the political division in the working class. (Proyect has argued incessantly that Lenin did not ‘create a new kind of party’, and rightly finds support for this view in Lih’s work. Yet he finds that the Comintern, including under Lenin’s leadership, did this. I could note that Gramsci’s recreation of the Italian Communist Party proceeded under Zinoviev’s slogan of ‘Bolshevisation’. The problem with the Stalinised Communist parties was not that they were or conceived of as ‘a new kind of party’, but that they had become opportunist, to the extent that they were, through their alliance with the Soviet bureaucracy.) That already existed, as Lenin first showed and still exists, as we must continue to try to research and understand today.

The problem posed by the labour aristocracy is not that suggested by Proyect—that the revolutionary party must engage with the different levels of consciousness in the worker movement (as indeed it must). Rather that problem is that some workers, although who that might be is not predetermined, will never reach revolutionary conclusions under monopoly capitalism. To offer an alternative metaphor: you can live with an appendix, which is a remnant of the past, but when the appendix ruptures, it must be cut out. In the imperialist phase of capitalism, opportunism, with its social basis in the labour aristocracy, is the ruptured appendix of the merger of socialism and the worker movement.

labour aristocracy - response to Jonathan Strauss

Jonathan Strauss says: “Lenin set out to understand the political consequences of the emergence of imperialism, or monopoly capitalism. His chief conclusion was that the superprofits of monopolising capitals provided the basis for sustained concessions to, and the resulting relative privilege of, a stratum of workers (the ‘labour aristocracy’). Among at least some of these workers, opportunism – a willingness to sacrifice the historic and general interests of the working class to their alliance with ‘their’ capitalists (their relationship of concessions and relative privilege) – and a ‘bourgeois labour party’, in one form or another, was inevitable”.

But in Australia today, who comprises the “labour aristocracy” – the “stratum of workers” enjoying “relative privilege”?

The majority of Australian workers are much more highly paid than the majority of workers in China. We can therefore say that most Australian workers are “relatively privileged” compared to Chinese workers. From a global perspective, most Australian workers could be considered as part of an international “labour aristocracy”.

But I don’t think this would be a useful thing to say. The use of the term “labour aristocracy” would tend to promote pessimism about the possibility of winning a majority of the Australian working class to participate in the struggle for socialism.

We do need to recognize that relative privilege has a significant effect on the consciousness of the Australian working class, especially in relation to issues such as immigration and the treatment of refugees. This makes the work of socialists much more difficult.

Nevertheless I think we can win majority support if we approach workers in a transitional way.

The economic and environmental crises affect, or threaten to affect, all Australian workers. This means that objectively they have an interest in abolishing the capitalist system that causes these crises.

It is our task to find ways of showing them that this is the case.

A political theory

Chris Slee fails to refer to my immediately following paragraph beginning "thus", that is, the conclusion (I argue) Lenin drew and that I reiterate for contemporary circumstances.

Let me state the issue bluntly.

The composition of the labour aristocracy can be determined by thorough research. The key to its determination is the structure of sustained concessions made to sections of the working class. I have sketched this out in my articles several years on the theory. But in any case this sociological analysis is secondary in the theory to its political implications.

Lih has pointed out that Lenin had great political confidence in workers. With the theory of the labour aristocracy, he maintained that confidence in the mass of workers, while explaining, in passing, the opportunism of a small proportion of workers who had, however, come to dominate the then existing "mass" worker organisations.

I have the same confidence. There is no tendency to pessimism inherent in adherence to the theory of the labour aristocracy.

Moreover this confidence includes the view that right now parts of the working class can be won to participation in the struggle for socialism, that they can be organised, and that their leadership (for example, union leaders) can be part of the same struggle. This is proven (again!) by the role played by our few Socialist Alliance union leaders. This is in contrast to those who claim union leaders are inherently conservative (rather than subject to a certain tendency to bureaucratism that can be combated by the influence of the revolutionary party), offering this as their explanation for workers' politics.

further response to Jonathan Strauss

Jonathan Strauss points out that I failed to refer to the following paragraph in his first message:

“Thus, in the past, opportunists could be included in the revolutionary party, because the expectation was that they would in good time cease to be opportunists, but now opportunists must be excluded from the revolutionary party. Revolutionaries should not orient toward the existing opportunist ‘mass’ organisations, but toward merger with the mass of workers, and working people generally, who would continue to need and to listen to the socialists. In any case, in the class struggle, a part of the relatively privileged workers, who were, after all, still workers, would also be part of the revolutionary movement: the proportion would only be determined in the course of the class struggle”.

I didn’t refer to this para because I was dealing with a different question, namely: “But in Australia today, who comprises the ‘labour aristocracy’ – the ‘stratum of workers’ enjoying ‘relative privilege’?”

I agree that relative privilege provides a social basis for opportunist politics. My point was that the MAJORITY of Australian workers are relatively privileged compared to workers in third world countries.

In my original article I explored some of the political implications of this fact (attitudes to immigration and refugees etc). But I also argued that these attitudes can be successfully challenged.

Jon says: “The composition of the labour aristocracy can be determined by thorough research. The key to its determination is the structure of sustained concessions made to sections of the working class.”

During the post-war boom, “sustained concessions” were made to the majority of the working class in the advanced capitalist countries. These concessions included higher wages, the welfare state, etc. (Some sections of the working class were excluded, e.g. Aboriginal people in Australia)

The concessions to the working class have been under attack since the 1970s, to varying degrees in different countries. But most workers in imperialist countries still remain privileged compared to most workers in third world countries.

This makes our task more difficult, but not impossible. I agree with Jon’s statement that “…a part of the relatively privileged workers…. would also be part of the revolutionary movement: the proportion would only be determined in the course of the class struggle”.

I think it is possible to win a majority of Australian workers to socialist politics – but it won’t be easy.

A "bourgeois labour party" and Marxist unity

I’m sure Tom Bramble, Chris and I all think “it is possible to win a majority of Australian workers to socialist politics – but it won’t be easy” (I reiterate: the theory of the labour aristocracy does not “promote pessimism” about this possibility). That majority – in fact, an overwhelming majority of workers – is simply what is needed for the achievement of a revolution here, for which we all struggle.

Where I disagree with both Tom and Chris (for the time being?) is that in accordance with the theory of labour aristocracy I believe a “bourgeois labour party” to which part of the labour aristocracy adheres is inevitable in imperialist countries, whereas:

• Tom considers the theory “exaggerates divisions within the working class and underestimates the potential for working class unity against the capitalist class” (as cited above). Specifically, he argues that because workers’ defence of relative privileges will not ultimately serve their interests, no section of workers will inevitably adhere to a bourgeois politics (see the concluding sections of his article).

• Chris rejects the theory of the “labour aristocracy” in favour of a concept of “relative privilege” because “the better-off sections [of workers] will often defend their relative privileges at the expense of other workers (though this is not inevitable)”.

Does this disagreement about the inevitability of a “bourgeois labour party” matter if there is agreement on what is needed for the struggle for socialism? Not if practical collaboration can be achieved, but the theoretical difference tends to undermine the chance of agreement on ‘what is to be done’.

Lenin’s perspective on party-building was, as Lih discusses it, one that was confident about the merger of socialism and the worker movement. I argued above that, under the conditions of the imperialist epoch of capitalism, Lenin reinforced his perspective through the theory of the labour aristocracy, even as the theory somewhat reoriented that perspective. The theory was only in passing an explanation of opportunism. By way of extension, it was not an explanation of reformism more generally. I agree with this perspective on party-building and those limitations on the theory of the labour aristocracy.

The alternative on the revolutionary left to the merger narrative (that is Lenin’s perspective) is the “worry about workers” thesis. Rejection of the theory of the labour aristocracy is consistent with upholding that thesis, because that thesis involves a belief that the merger of socialism and the worker movement cannot develop in “normal” times. The theory is discussed as an explanation of reformism (see the first paragraph of Bramble’s for its discussion in these terms) to which other “explanations” for reformism are counterposed. In the case of the International Socialist tradition, from which Tom hails, two such are chief: the domination of a labour bureaucracy that is inherently conservative (the use of the term “bureaucracy”, rather than “apparatus”, ensures a circular argument, since the bureaucracy is ... bureaucratic) over a relatively inert worker mass; the material effects of the long boom in support of a broad reformism, and the ideological lingering of that reformism after the end of the long boom. (Neither explanation holds up in the light of the experience of the revolutionary worker movement, starting with what developed as the Bolsheviks. This occured during the two decades of long boom before WWI: by 1912 (through to 1914), for example, the Bolsheviks, the “majority-ites”, had the most broadly read and financially supported publications, and had won leadership of a large majority of the Petersburg and Moscow unions and all the Duma parliamentary positions elected by workers.)

Thus, differences about the theory of the labour aristocracy map over, albeit indirectly, into differences about party-building perspectives.

Note

Chris has explained that Tom’s article “says that the term ‘labour aristocracy’ is ambiguous. Pointing out that different people have used it in different ways, [Tom] asks who is included: ‘Is it the union bureaucracy and the parliamentarians? Plus the skilled tradesmen? Or, indeed, is it the entire Western working classes?’ Chris, for his own part, offers that: “During the post-war boom, ‘sustained concessions’ were made to the majority of the working class in the advanced capitalist countries. These concessions included higher wages, the welfare state, etc. (Some sections of the working class were excluded, e.g. Aboriginal people in Australia.) The concessions to the working class have been under attack since the 1970s, to varying degrees in different countries. But most workers in imperialist countries still remain privileged compared to most workers in third world countries.”

Chris has in fact quite rightly answered Tom’s questions with the answer “none of the above”, since the use by different people in different ways of “labour aristocracy” reflects the many non-Marxist uses of the term (“class” is also used by non-Marxists, is thus used in different ways and “is ambiguous”). This includes all those who argue that the labour aristocracy’s sustained concessions are gained at the expense of other workers. Monopoly superprofits , which fund those concessions, are in fact gained from other capitalists and petty producers, without changing the prices of commodities.

Chris, however, has still probably exaggerated the size of the labour aristocracy in the Australian case. If the argument is, as I have made elsewhere, that the “sustained concessions” to some Australian workers between about 1920 and 1970 were primarily the idea that male wages should meet a family’s needs rather than be market-driven, higher “margins” for skills than what was needed to obtain the skills, and a degree of union empowerment, then not only Aboriginal people but women generally must be excluded, as must many migrant workers. Perhaps a majority of employed workers were labour aristocratic, but certainly not a majority of all those who might become part of the worker movement.

More recently, the labour aristocracy has narrowed and changed in its composition. Certainly the majority of workers in rich countries remain better off than those in the global South, but aristocratic concessions were and are only a partial explanation of this.

The argument that workers

The argument that workers get paid more cos their productivity is higher doesn't refute the argument that there's a labour aristocracy. Its basically a moral statement that if they're more productive they "deserve" to get their higher wages. So what?