France & Mali: Left assesses Mali military intervention and its aftermath

[Click HERE for more on Mali.]

By Roger Annis

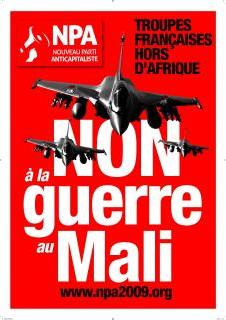

March 30, 2013 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – Two leading voices against France’s military intervention in Mali, Paul Martial and Bertold du Ryon, have written a comprehensive dossier on the subject. It is published in the weekly print and web bulletin of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) in France, Tout est à nous, dated March 14, 2013 (#186).

The dossier is a valuable overview of the situation in Mali and stands out for its unyielding opposition to the intervention. That’s no small feat in a France that is awash in national patriotism and anti-Islamic prejudice over the issue.

The intervention was planned and initiated by a Socialist Party president and government. The Communist Party of France is an enthusiastic backer. Sadly, leading spokespeople of the Left Front (Front de gauche) electoral coalition (in which the Communist Party plays a prominent role) have chimed in for the war.

The dossier reviews the economic and strategic interests that have propelled France’s intervention. These include the protection of its resource wealth, notably the vital uranium mines in neighbouring Niger.

The authors describe France’s role more broadly in the region, “which it doesn’t deny, and which is acknowledged by its partners, to assure the stabilization of the French-speaking African countries for the benefit of multinationals exploiting mineral riches and seizing control of arable lands” [translation]. The dossier looks at recent flashpoints of the French role.

France has intervened consistently in Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) over the past 10 years, including spearheading a coup d’etat in 2011 that decided the outcome of a disputed presidential election. It has repeatedly intervened in Chad to assist in putting down rebellions against the dictatorship of Idriss Déby Itno. Not coincidentally, the Chadian army has been fighting alongside France in northern Mali this year, the only African army to do so. If they were writing the dossier today, the authors would add the Central Africa Republic to the list. There, the ruling dictatorship aided and abetted by France over the past 10 years is coming apart.

The dossier examines the grave humanitarian issues facing the Malian people. These include the hundreds of thousands of refugees who are victims of the drought conditions in west Africa in recent years, those who were driven out of their settlements in northern Mali as a consequence of the Mali army’s military offensives of recent years, and more recently the smaller numbers of people who have been victims of the well-armed and -financed, right-wing Islamist forces that muscled their way into the north of Mali during the past several years.

The dossier examines sympathetically the long-standing, national rights struggle of the Tuareg national minority, whose homeland includes parts of the north of Mali.

Summarising how France views what it has accomplished in Mali, the authors write, “France and its elites believe they have re-legitimized a prominent political, economic and military role for themselves in their post-colonial ‘sphere of influence’ [west Africa]. But even if the peoples of the region take some comfort from the departure of the jihadists,[1] they will not be duped about the intentions and neo-colonial interests of France” [translation].

The dossier in Tout est à nous and related analyses of Mali by these and other authors leave some important aspects of the situation unstated or even misrepresented. This contribution will attempt to fill in the story.

Tuareg history

Martial and du Ryon tell much of the essential story of the national rights struggle of the Tuareg people. But they leave out several important chapters. The most important is the repression directed at the Tuareg in recent years by the Mali army and government. While it is true that the Mali government has conceded measures of autonomy and social/economic development in the north at different moments over the past few decades, it is also true that these measures were given grudgingly by the Mali side and that much of Mali’s elite and army tops never really accepted them. (A similar process has occurred in neighbouring Niger.)

A major factor in the army coup of March 22, 2012, was the accusation by army officers against the government for having negotiated autonomy concessions in the first place and for not adequately supporting the army in its military efforts to undo them. The Mali army has been waging a war of considerable intensity against the north in recent years. Martial and Du Ryon do not mention this in their summary of Tuareg history.

Nor do they mention the serious, hair-raising even, reports of human rights violations committed by the Mali army as it has re-entered the north in the wake of the France invasion. These have been extensively documented by some French media and by leading, international human rights organisations. The Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) has condemned France for refusing the MNLA’s demand that the Mali army not be permitted to re-enter the north.[2]

The website of the MNLA as well as sympathetic websites (Toumast Press) contain detailed reports of kidnappings, summary executions, forced dislocations and even poisoning of water wells in Tuareg regions. The practice by the Mali army of poising water sources in this desert region dates back to the very harsh and violent battles in the early 1960s waged by the newly independent Mali against the Tuareg, then a nomadic people being forced by a range of circumstances into sedentary lives.

The authors stress that the Tuareg are but a minority of the Mali population, even in the north, and that the MNLA does not speak on behalf of the entire Tuareg population. These are important matters, but they do not negate the Tuareg claim for national rights. What’s more, there are other nationalities in the north that also face political exclusion and discrimination. They are less socially cohesive and less well represented politically, so the relative strengths of Tuareg political organisation is likely to their benefit.

The authors criticise the MNLA for several key political decisions, including the temporary alliances it formed with rightist, Islamic forces in 2011/2012 in its effort to end the Mali army’s operations, and its more recent, limited collaboration with France in operations against the Islamists since the French invasion. They write, “The totally adventurist and unprincipled political line of the MNLA has caused much harm to the Tuareg cause.” There is truth in this claim, but a description of the incredibly difficult circumstances in which the Tuareg are asserting their rights would help in presenting a fair, overall picture.

The authors mention the summary execution of up to 100 captured Mali soldiers in the northern town of Aguelhok on January 24, 2012. They acknowledge that accusations against the MNLA are unproven. The massacre is under investigation by the International Criminal Court.

Weakened and bloodied Mali

Martial’s and du Ryon’s account of recent years in northern Mali reports on the rights violations and ruthless conduct of the rightist Islamists in the north. Though mainstream press reports on the subject are no doubt exaggerated, it is certainly a major concern of the Mali people and an important story to tell. But the national minorities in the north were also victims of the Islamists. Their side of this story is largely untold.

Mainstream press (including, lately, a lengthy article in the New York Review of Books) printed wild stories that the few hundred (or call it a few thousand) Islamists were poised to take over the entire country of 15 million people! This was also the pretext peddled by France when it delivered its snap announcement to invade Mali on January 11, 2013 (the announcement was snap, but the invasion plan certainly was not).

Too few are asking how it is that a country of 15 million people with an army trained and supplied by the US and Europe for at least the past eight years would apparently be so vulnerable. But the truth is that Mali is a desperately poor country, one of the poorest on Earth, going nowhere but backwards in its social and economic development, and its people have been excluded from any meaningful role in determining their future.[3]

Many in the mainstream media have presented Mali as a former oasis of democracy in West Africa. It was anything but. Bruce Whitehouse, author of the blog Bridges from Bamako, writes, for example, that Mali’s elections have consistently had the lowest voter turnout in west Africa, never higher than 50% of the voting-age population and 40% of registered voters.

“At a fundamental level”, he writes recently, “most Malians didn't feel represented by their elected officials and the problem was growing worse. According to the Afrobarometer survey, public satisfaction with Mali's democracy had been falling for a decade by the time the [2012] coup took place.”

In other words, the people of Mali are victims of a neocolonial regime and its close ties to the US and France. All of them, or at least 99 per cent or so, have a common interest in finding solutions to the economic, political and environmental crisis that is wracking the country.

Mali’s political left

Unfortunately for Malians, much of its political left is associated with the moderate left in France that initiated or supported the intervention. It has little or nothing to offer to them. An example is the African Solidarity for Democracy and Independence party (SADI). A participant in previous governments in Mali, today it has a small number of elected representatives in the national assembly and in local governments. It is strongly opposed to self-determination for the national minorities in the north, apparently treating the national borders in west Africa that were laid down by the imperialist powers decades ago as all but sacrosanct.

The party supported the military coup d’etat last year. It thought it was backing an anti-imperialist act because army and coup leader Amadou Sanogo made demagogic declarations against the limp, foreign protests against his coup. But less than a month after his coup, Sanogo did an about face and said he would support foreign intervention in order to help him restore “order” to the country. Sanogo and SADI share an opposition to the national minorities, especially toward the Tuareg who delivered a succession of humiliating defeats to the army in 2012.

SADI is presently offering a critique of the French intervention. But its main criticism is that France is not facilitating a more direct role for the Mali army in the military operations in the north. This is reminiscent of some on the political left in Haiti who supported the coup d’etat of February 2004 and then several years later began to offer critiques of the United Nations MINUSTAH military mission brought in to run the country. Their criticism is not worth much if it doesn’t explain why MINUSTAH is there in the first place.

Tout est à nous features an interview with a leader of SADI in its most recent issue. The interview is taken from a valuable and informative website edited by Paul Martial, Afriques en lutte (Many Africas in Struggle). Afriques en lutte is a broad-based information service and it does its readers a service by publishing an interview with SADI. But the NPA journal should provide necessary background so as to not leave its readers a false impression of SADI.

No to the French intervention

In numerous articles in Afriques en lutte and Tout est à nous, Paul Martial has stood against the chauvinist tide and explained that nothing good can come to the people of Mali and of Africa from the French intervention. The political organisation of which he is a member, Gauche anticapitaliste (GA, Anti-Capitalist Left), a constituent part of the Front de gauche, has been rather low key in speaking out against the French intervention. Martial has not.

But ongoing discussion is called for on the left in France in its efforts to assist the Mali people in resisting the foreign takeover and finding a new, anti-colonial course for the country. For example, Martial co-authors an article in the second issue of the joint-left publication of which GA is part, Traits d’union (March 2013), in which the authors write the following:

The French troops must withdraw [from Mali]. The Mali army must be given the means and equipment to protect the north against a return of the jihadists, including support from African forces respecting the country’s sovereignty. This is the only course that could make possible a political solution—the holding of a national conference to redefine the rights of the Mali people, the control of their natural resources and the building of a independent and democratic state [translation].

Earlier in the same article, they write, “Mali needed assistance from the UN or the African Union in order to get rid of the narco-jihadists that had established a regime of oppression and terror.”

These are frankly wrong recommendations. In the 60-year plus existence of the United Nations, there has been only one UN Security Council-authorised military intervention that could arguably be said to have been in the interest of a people. That was the intervention into East Timor in 1999 that ended an Indonesian genocide. It was successful because a broad-based and relentless movement of international solidarity was able to exercise defining influence over the course of the intervention (of which the Australian military was the largest component).

Conditions for a positive outcome to foreign intervention today in Mali do not exist, regardless of whether the intervention is in the name of the UN or the African Union. Different political and military options within Mali remain available, along the lines of a political realignment in the country that, among other measures, would respect the political autonomy of the north. The latter would pay serious heed to the demands of the Tuareg people to get the Mali army out of their territory and lives.

A joint declaration on Mali by three parties from Burkina Faso, Benin and Ivory Coast describing themselves as communist was published on Afriques en lutte on March 22 and it sounds a very troubling signal. The statement is harshly opposed to the national minorities in Mali. Terming the MNLA “a French-made creature”, the statement complains that the Mali army has been prevented by France from entering certain areas of the north and engaging in fighting (the area surrounding Kidal where the fiercest killings by France and Chad against Islamists have been taking place and where there is a large Tuareg population).

Broader region

The broad backdrop to all the events in Mali has been the militarisation of the entire region of west Africa that has been spearheaded by the United States since its humbling in New York City on September 11, 2001. In 2005, the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership was created with a view to drawing all the neocolonial governments and armed forces of the region into a pro-imperialist alliance. Martial and du Ryon overlook mentioning this all-important part of the story in their dossier.

They also make no mention of the post-intervention, imperialist political/military plan for Mali, which is to create a Haiti-style, foreign political and military occupation force to run the country for the foreseeable future. Even worse that the Haiti mission is the intention to create two forces—one a “traditional” Security Council occupation force and the other a military strike force headed by France and formally accountable to no one but itself. (This second force was announced only recently, several weeks following the publication of Martial and du Ryon’s dossier.) Barring a miracle, this plan will gain assent at the UN Security Council in the coming weeks.

While numerous groups on the left in France have spoken out against the Mali intervention, the NPA has distinguished itself with the consistency of its pronunciations, published articles and protest actions. Afriques en lutte has similarly distinguished itself with the scope of its online reporting. They and others on the French left who are speaking out are crucial allies as the peoples of Mali face extraordinary difficulties in the wake of the consequences of the French intervention and renew their struggles for sovereign and socially-just homelands.

[Roger Annis lives in Vancouver, Canada, and reports on Mali in English and in French on his website. His previous article on Mali was titled "No Peace or Reconciliation in France-controlled Mali" and was published on February 25, 2013.]

Notes

[2] Azawad is the name given by the Tuareg people to the homeland that they share with other national minorities and that encompasses territory in five countries—Algeria, Libya, Niger, Mali and Mauritania.

[3] The Sahel region of Africa, where Mali is located, is experiencing a long-term drought. The Sahara Desert is expanding by 48 square kilometres per year according to some accounts. The trend has led to mass migrations, malnutrition and thousands of deaths. Mainstream news reports on Mali have confused matters enormously, conflating the humanitarian consequences of long-term climate trends with the conflict with Islamic fundamentalists.

Malian left?

Are there any other leftist parties in Mali besides SADI?