Lessons from Spain: grassroots democracy and the movements against capitalism

"Podemos, whose decision-making process is based on online voting by a passive mass membership of 300,000, is a highly centralised operation that is in many ways the polar opposite of the grassroots democracy of 15M."

For more on politics in Spain, click HERE.

By Dick Nichols, Barcelona

May 11, 2015 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – If some people I know from the more cynical or disillusioned end of the Spanish left spectrum were to reflect on the topic of our discussion tonight---“Grassroots democracy and the movements against capitalism: lessons from Spain”—they might be tempted to make a rather acid commentary, maybe something like this:

“Grassroots Democracy? However much of that was expressed in the indignado movement of the squares—that began four years ago now (on May 15, 2011), when millions came out in over 80 cities and towns—it’s more or less evaporated by now.

“Movements against capitalism? Where are they? If we’re not talking about marginal revolutionary groups, there are no movements against capitalism worth talking about. What we’ve got is an uneven pile of movements of resistance, usually unsuccessful, against different aspects of capitalist austerity.

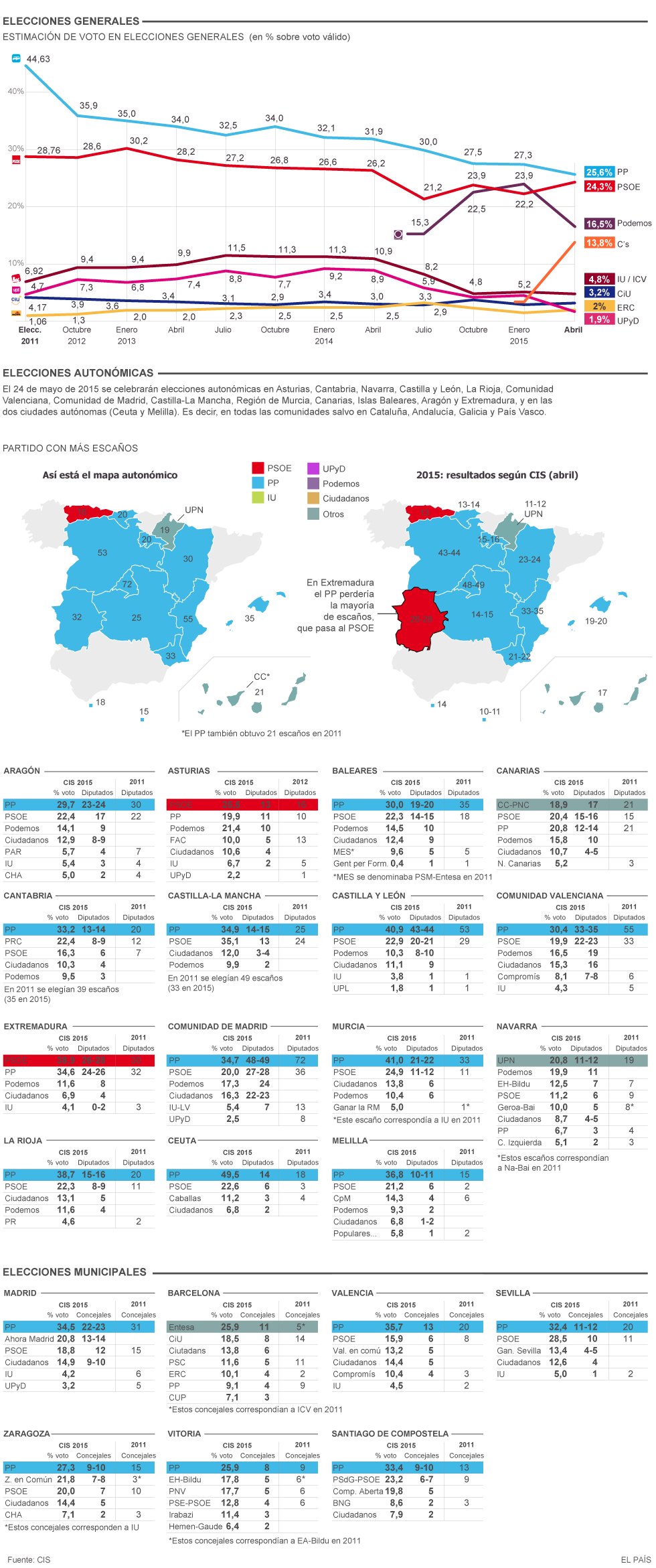

“Lessons from Spain? Only one—don’t get yourself into the awful mess we’re in now. Here, despite the fact that support for the two major parties that arose from the post-Franco dictatorship transition, the ruling conservative People’s Party (PP) and the social-democratic Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE), has collapsed from over 80% to around 40-50%, no clear alternative for a progressive government that fights capitalist austerity instead of implementing it is yet on the horizon.

“That’s means—horrible thought—that the two-party system could even recover, or that the establishment will have time to organise its “spare wheel”, the Spanish-centralist and anti-Catalanist Citizens party. This is the supposedly civilised alternative to the corrupt, socially reactionary and semi-clerical PP. A recent poll shows 46% of ‘big investors’ support Citizens,.”

This hypothetical observer might be tempted to add that Spain isn’t Greece, neither objectively nor subjectively, and justify that judgement like this:

“First, the economic crisis, although deep, is nowhere near as catastrophic as in Greece. Indeed, Spain is now getting brownie points from the European Commission for its economic recovery.

“Second, there is no SYRIZA in Spain. There are forces on the left who thought they were already SYRIZA, like the United Left (the traditional left alliance to the left of the PSOE, centred on the Communist Party of Spain but with other forces, and having been around since the mid-1980s).

“And there’s Podemos, which aspires to be the Spanish SYRIZA, but as yet has nothing like SYRIZA’s presence at all levels of society nor its levels of organisation.

“If what’s happening in Podemos is anything to go by, its most recent attempts to win the so-called ‘middle ground’ as shown by its framework platform for the May 24 regional elections (in 13 of Spain’s regional governments), shows that it is becoming like the parties of the ‘political’ caste that it has been denouncing.

“That’s what Juan Carlos Monedero, co-founder of Podemos with Pablo Iglesias, said when he left the party on April 30, saying he felt ‘deceived and betrayed’.”

Well, how accurate would such an assessment be? My reaction from living here in the Spanish State for over four years would be a series of “Yes, buts”.

First, it’s true that the economic crisis has not been as deep as in Greece, but that’s actually not saying much—the criminal shrinking of the Greek economy by the bailout conditions imposed by the Troika (the European Union, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund) has set a world record in policy-induced downturn that will last for decades--greater than anything since the Great Depression.

However, Spain shares with Greece a youth unemployment rate of more than 50%—not surprisingly one of the organising groups within the indignado movement was called “Youth Without a Future”—and is being subject to the same Eurogroup austerity recipes as Greece.

What’s more, the demolition of workers’ and trade union rights that the SYRIZA government is refusing to accept in its present negotiations with its Troika creditors, is already under way in Spain, with results like €2-an-hour wages and “your rights at work” that have simply vanished.

The Spanish economic crisis didn’t generate the 30-plus general strikes we saw in Greece from 2010-early 2013, but it generated the vast outpouring of popular outrage that was the indignado movement. And that was also driven by specifically Spanish horrors—like taxpayers’ €61.2 billion bailout of the collapsed banking system (done in this form to prevent a repetition memorandum in Europe’s fifth-largest economy of a Greek, Portuguese or Irish-style Troika).

These policies, expressed in the oxymoronic “expansionary austerity”, introduced from 2010 by the Troika powers, produced in Spain a notorious 2011 constitutional amendment that put repayment of interest on government borrowings above all other budget priorities—around €35 billion annually—helping devastate economy and society.

This resultant social crisis has given rise to the famous Mortgage Victims Platform (PAH) and the white and green “tides”, the movements of public health and education workers and users against privatisation of services and against the truly brutal cuts to funding (such as the 20% cut we’ve had over five years here in Catalonia).

Differently from Greece, these “tides”, in which mass assemblies of the workers involved replaced, or worked in parallel with, existing trade union structures, have had two major victories. The white tide of health workers in Madrid stopped practically all PP privatisation of the regional health system, and the green tide on the Balearic Islands put an end to the crude attempts of the local PP government to replace the Balearic variant of Catalan with Castilian (Spanish) as the language of school instruction.

The Mortgage Victims Platform is Spain’s most implanted and respected social movement, self-organising the resistance of families marked for eviction by the banks and putting the whole question of the real-estate finance-sector nexus in the forefront of political consciousness.

Indeed, we could say that its slogan, “Rescue People, Not Banks”, has become the motto of the present phase of social resistance and breakdown of the old two-party system.

(For a good idea of the work check their website for a very vivid, just-released documentary, subtitled in English, on a week of its work in Barcelona in March 2014).

Impact and lessons

It is these “new movements”---that sprung into being outside the traditional organisations of the working class—especially the rather bureaucratised main Spanish trade union confederations that just gave up on organising resistance after a couple of national days of action in 2010 and 2011—that have given Spain its most recent experience of mass grassroots democracy.

They schooled a whole new generation in political action, revived older generations of activists and created a political culture that drew on and updated very Spanish left traditions (like “assemblyism”, decision making by open mass meetings).

I don’t have time to convey the extraordinary richness, complexity and contradictory dynamics of these movements, but here is a summary of the main impacts.

- They created a huge, often exhausting, debate about what a democratic decision actually is, and the pros and cons of 100% consensus, partial consensus, simple majorities etc. At bottom this has not been a theoretical or technical debate, but one about how to create a new legitimacy as against “the institutions” and “the political caste” that arose out of the 1978 compromise settlement between the dying Francoist dictatorship and the anti-dictatorship forces. That consensus is increasingly seen as bereft of democratic legitimacy;

They inspired the growth of new forms of struggle to fill the vacuum left by the default of the traditional trade union confederations. In particular, they helped inspire the emergence of the Marches for Dignity (for Bread, Work and a Home) which led to a 1 to 2 million strong convergence on Madrid in March 2014.

They forced everyone on the left who is looking for solutions to the great unresolved questions of democracy in the Spanish state to rethink them in relation to this new upturn in social resistance.

The most important is the right of the nations of the Spanish state to self-determination, most immediately in the case of Catalonia, which will have an election-as-referendum on September 27 (because the PP national government has refused a Scottish-style referendum). These questions also include the issue of a new constituent process that would allow people to decide whether people want to retain the buffoonishly corrupt Borbon monarchy, whether they want to retain a voting system that aims to entrench two-partyism, and a host of other issue left over from that compromised and half-completed “transition to democracy”.

These movements also posed an exacting test for the practice of the already existing left—the “institutional” left opposition, if you like—about what in their methods and culture of decision making and candidate pre-selection had to be changed.

The left that was most affected by this challenge was the all-Spanish left (United Left, based around the PCE and Equo, the Green party), but the challenge also percolated through to those left-nationalist and left-regionalist organisations that may have thought themselves immune from any all-of-Spain trends.

A critical moment in this clash of new and old occurred in the negotiations between the newly formed Podemos and the United Left over the conditions under which they could go to the May 2014 European election on a single ticket. Their programs were very close—totally reconcilable, I would say—but the United Left refused to accede to the key Podemos demand of open primaries to preselect candidates because they had already worked out whom they wanted their candidates to be.

That refusal led to Podemos standing in its own name, with the spectacular results we all know, and was the beginning of the surge that took it to the leading position in some Spanish polls (and sent the United Left into a decline from which it is being challenged to recover).

And, they legitimised the political practice of new left, explicitly anti-capitalist parties—specifically the Galician left-nationalist party ANOVA and the Catalan Popular Unity Candidacies (the CUP)—that were closest to the mass-assembly based indignados culture, being also born of local and social movement activism and struggle. This was in contrast with the older left that had its roots in the anti-Franco struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, and which had been in parliament—and regionally even in government with the social democracy—in the following years.

Political representation of resistance to austerity

Finally, they demonstrated again that “the people united will never be defeated”, a lesson that has had positive spill-over effects in the left party political sphere. For example, in the May 24 municipal elections here we are seeing a swag of united left tickets, most importantly the “Barcelona Together” campaign for the Barcelona city council.

However, the successes and failures of these multi-faceted movements of mass resistance—absolutely necessary if austerity policy was to be confronted—increasingly highlighted the vital challenge that they, of themselves, could not meet.

This was the issue of giving political voice to an anti-austerity social majority and of creating a political power pledged to create a socially just, democratic and ecologically sustainable alternative and powerful enough to win government.

That challenge is posed in all the European “peripheral” countries. However, the specific national trajectory that will need to be followed to reach that goal is very specific. For instance, from the viewpoint of the Spanish state, SYRIZA’s trajectory in Greece, which saw that coalition formed in 2004, then take a lead in anti-austerity struggles from 2010 onwards, then take a majority of PASOK votes in the May 2012 election, then take Greek Communist Party (KKE) and PASOK votes in June 2012, and then emerge victorious in January this year, frankly looks a bit like a “stroll in the park”.

It was anything but that, of course, but there can be no repetition in any of the other European states most affected by austerity of that SYRIZA pathway, not the least because the European capitalist establishment is hell-bent on preventing that repetition and on taming or destroying the SYRIZA government itself.

For, just as in the January Greek elections, the Spanish political battleground is just as much about Europe as it is about Spain. It’s about stopping the spread of anti-austerity sentiment, about proving that it’s really true that “There Is No Alternative” to austerity driven in the name of the competitiveness of big European capital.

That said, it’s vital to note that the emergence of Podemos is a big step down the road: it has given a political voice to millions who did not feel represented by the “old parties” of the “caste”, even if that description was often unfair to the United Left, which over the years has many honourable struggles to its credit.

Second, however, the construction of Podemos has been along lines quite different from the grassroots democracy of organisations like ANOVA and the CUP—and, increasingly, those parts of the United Left that have been learning from their difficult experiences of recent years.

Podemos, whose decision-making process is based on online voting by a passive mass membership of 300,000, is a highly centralised operation that is in many ways the polar opposite of the grassroots democracy of 15M.

How much it has to be that, and how much this structure is leaching life from its “circles” (branches) is the subject of debate and struggle within Podemos itself, an issue I don’t have time to cover here.

However, such debate and conflict is inevitable in a formation that has to meet four daunting challenges:

To be an adequate and convincing electoral alternative, and engage in a winning battle on three fronts—against the PP (not too difficult), Citizens (tricky, because they’ve borrowed 40% of the Podemos rhetoric in order to betray what’s radical in the Podemos program) and (most difficult of all) the PSOE, whose essential line is that they alone remain the practical alternative government to the PP—especially after their win in the snap Andalusian elections in March.

To overcome the Spanish-centralism still prevalent in much of the Spanish left, a relic of the hegemony of Stalinism during the Spanish Civil War, especially on the most fraught question of all—the right to self-determination of the nations that make up the Spanish state.

To link and balance this struggle for party-political predominance with the ongoing, but now more muted, social struggle.

To counter—in real practice, not rhetorical declamation—the old political culture of clientalism and job-for-the-boys. This is much easier said than done, as the establishment of a new party with up to 30% in the polls has attracted lots of politically undesirable elements to it.

The battlefield situation

In the overheated and volatile political atmosphere that we are living through in Spain support for all parties can shift with unprecedented speed.

The latest polls give the PP, PSOE, Podemos and Citizens between 14% and 27%—effectively a quadripartite system, with the rest of the vote divided among the “old alternative left”, the United Left, the “old alternative right”, the Union for Progress and Democracy (UPyD), and the various nationalist parties—right (like the Basque Nationalist Party, ruling in the Basque Country and Convergence and Union, ruling in Catalonia) and centre-left and left.

The latest polls also show, both regionally and nationally, that the percentage of undecided voters has halved to 9%, with a large proportion of them going to Citizens, already widely known as “the Ibex 35 party” (name of the Madrid stock exchange index).

It is as if the fence sitters, fed up with the PP and PSOE, and finding Podemos too radical for their tastes, have just been supplied with the right product in time—an apparently powerful detergent to clean away the remaining Francoist filth while leaving underlying Spanish economy and social relations untouched.

Citizens thus fills a gap of representation that was not being met by any other party. Its message is targeted at the illusion, understandably widespread in middle-class and professional circles, that “Spain could be a ‘normal’ European power” if only it was rid of corruption, feudal remnants like church privileges and ancient national conflicts.

With just over three weeks to go to the May 24 municipal elections , to be accompanied by regional polls in 13 of Spain’s 17 regions, the main polling trends show that Citizens will be tested in quite a few regions and cities after results come in.

These polls confirm the trends already visible after the March 22 poll in Andalusia. One or other of the old parties will retain a relative majority (like the PSOE in Andalusia) while the new parties will have insufficient support to form government.

At the same time, however, none of them will want to be responsible for installing either of the old parties in government. In Andalusia, for example, the negotiations involving the PP, Podemos, Citizens and the United Left that would allow the formation of a minority PSOE government have been dragging on for weeks.

If the polls are accurate, the likely scenario after May 24 is, first, that the PP will lose nearly all its absolute majorities, even in heartlands like Castilla-Leon and Murcia. Some of these will be more than halved, especially in the centres of greatest PP corruption (like Valencia). However, in many regions and cities, the right as a whole (PP plus Citizens plus others) may well hold onto the majority.

In a number of regions the Citizens vote will therefore be decisive in determining government (such as the Madrid region, Castilla-Leon, Extremadura and Murcia).

The problem for Citizens is that it could vote to maintain the PP in government, but will it want to be exposed as simply a prop for Spain’s ruling party of austerity and corruption in the run-up to the most important election of all, the November national poll?

In other places (like the Balearic Islands, Valencia and Cantabria,) the ruling PP looks like losing to quite politically variegated combinations of the PSOE, United Left, Podemos and regionalist forces. Will these be able to construct an alternative government? Will they at least be able to reach an agreement that allows part of them to govern in minority?

In regions and cities presently run by the centre-left coalitions (like Asturias) those majorities will become bigger, on the reasonable assumption that Podemos, which will now hold the balance of power in many, will support a left government against the right.

These likely results, influenced by the rise of Citizens, confirm that over the years of the Great Recession there has been a broad left shift in Spanish society and politics, but not yet one big enough to put a left government—one covering Podemos, the United Left, with left- and centre-left nationalist support in Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia—into power.

One possible exception is Barcelona. There the coalition Barcelona Together, involving Podemos and Initiative for Catalonia-Greens-United and Alternative Left and other left forces could emerge as the most supported ticket. This would be in large part due to the popularity of its mayoral candidate, Ada Colau, the former spokesperson of the Mortgage Victims Platform.

If Barcelona Together, the left-nationalist Popular Unity Candidacies and the centre-left nationalist Republican Left of Catalonia manage to win a majority of council seats, Barcelona city council could emerge from May 24 with the most left-wing administration in the Spanish state. That would have repercussions well beyond Barcelona, and well beyond Catalonia.

However, given the general social and political balance, what is needed most for progressive political advance is one or both of two events: a new wave of social struggle, especially one involving organised labour, effectively silent for three years now, and/or a majority vote for Catalan independence in the September 27 Catalan election-as-referendum.

That would shake up politics in the Spanish state like nothing else.

[Dick Nichols is Green Left Weekly and Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal’s European correspondent, based in Barcelona. This is an edited and slightly expanded version of a talk presented to the May 7, 2015, Sydney Politics in the Pub. The other speaker was Professor Simon Tormey, of the University of Sydney’s School of Social and Political Sciences.]

Theses on Podemos and the ‘Democratic Revolution’ in Spain

(Translation by Eric Canepa)

Even if one almost always goes wrong with such prognoses, the fact is that the Spanish state is facing the biggest rupture since the end of the Franco dictatorship. In several large cities, the left radical-democratic lists of the Guanyem / Ganemos Initiatives have real chances of winning the mayoral elections in May. In recent months in Catalonia, millions were on the street calling for the democratic right to self-determination, to which Madrid could only answer with new prohibitions. But it is above all the left party Podemos (We Can) that is dominating Spain's political landscape. According to some current polls, Podemos, though founded only in January 2014, is the strongest party today with an almost 28 per cent voter approval, one year before the parliamentary elections.

Guanyem initiative in Barcelona. [Photo by David Samaranch and Cristina Mañas.]

What is more remarkable about Podemos than the poll results, which can merely be volatile snapshots of the moment, is the social mobilization that the organization set in motion. 900 Podemos base groups, so called circles, have formed throughout the whole country. Almost 10,000 people took part in the party's founding congress in October. And in municipal district assemblies hundreds of neighbours discuss the crisis, capitalism, and ‘real democracy’ – and in this case ‘neighbours’ means literally neighbours. Podemos has left the subcultural milieus behind.

The level of debate is astounding, determined as it is, on the one hand, by a pragmatism directed at the 2015 elections and, on the other, by sharp criticism of neoliberalism and bourgeois political routine.

Crisis of Representation

Podemos is the expression of a crisis of representation that has gripped many countries with a neoliberal regime since the 1990s. That is, Podemos is not the product of a gradual process of growth but appears to have emerged out of a political vacuum and is expanding in an explosive manner. No existing political structures (such as trade unions, the larger NGOs or the media) have supported the project; the party activists – most of them under 35 – belong to the generation characterized as apolitical, and its immense popularity among the population is not easily explained. In the Spanish mainstream, left positions were decidedly marginal until 2011.

Despite this, Podemos naturally did not come out of nowhere. Its bases are the new anti-institutional protest movements that have repeatedly filled public squares and streets in the Iberian peninsula. That Podemos is more than a fleeting protest party like the Pirates in Germany has mainly to do with the 15M Movement and the Mareas.

The 15M Movement (public square occupations with the demand for ‘real democracy now’), which many on the left at first regarded with suspicion and at the very least was seen to be naïve and tending to apoliticism, has brought forth a new generation of activists and new forms of politics and made possible a tremendous repoliticization – both internally and externally.

The crucial factor in the 15M Movement is its intuitive linking of criticism of capitalism with democratic demands. Starting with the concrete European experience, in which there is no longer a distinction between the economic and social policy of socialists and conservatives, the movement has problematized the systemic limits to democracy in the bourgeois state: i) The democratic process ends where the interests of big capital, that is especially the banks, begins. Before the outbreak of the crisis, Spain's debt ratio was 40 per cent under the German level. Only when Madrid was forced by the EU to bail out private Spanish banks (and thus also German investors), did the state deficit explode. The cuts in healthcare and social services already made by the PSOE governments showed that in an emergency government executives have the function of carrying out underlying power interests. ii) However, political parties also seem to be increasingly standing in the way of democracy. With the ‘political class’, distinguished by professional politics and closed decision-making circuits, a specific social group has emerged with its own strategies of power and self-enrichment. In Spain, the political apparatuses are strongly shaped by the real estate boom of recent decades. The awarding of building permits and construction contracts, as well as state oversight of public savings banks (which have flourished in conjunction with the construction industry) guaranteed the ‘political class’ lucrative (mostly illegal) sources of income.

In contrast to what media reports suggest, the 15M Movement has in no way dissolved itself after the ebbing of the 2011 street protests but has spread throughout society. Thus we have seen the emergence, among other things, of the so-called mareas, protest movement for the defence of the public education and healthcare systems, in which public service employees come together through patients’ initiatives and patient and refugee groups, or the movement against forced evictions – the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH), a coalition of base groups, which connect direct action, solidarity and case-oriented self-help in a remarkable way. There is also a revival of labour organizations: In Andalusia, for example, activists of the base trade union SAT organized the non-violent redistribution of food purloined from supermarkets. The mareas in the healthcare and education sectors are supported by local groups of various smaller and larger trade unions. And, finally, the Marchas de la Dignidad, nationwide protest marches on Madrid, mobilized a million people in 2014 once again.

These movements made it clear that there is a social majority beyond the political apparatuses. But it also became clear – and this in turn led to thinking processes among the anti-institutional left – that the neoliberal regime has no difficulty in sitting out social protests (as Germany's red-green government did with the Hartz IV protest at the beginning of the 2000s). Since the use of force is no longer an option, as it was for the labour movement of the twentieth century, a central means of pressure in adversarial politics is missing. ‘Citizens' protests’, which duly request permits from the authorities and do not disturb capitalist business as usual, do not affect the neoliberal regime. It is not prohibited to have a different opinion because in the end it has no practical consequences.

Transforming Political Power

Against this background, the social movements in Spain faced the question of how these constant mobilizations could be transformed into real power from below, into poder popular. The Podemos and Guanyem inititiatives – and this distinguishes these phenomena from other organizations of the European left – aim not simply at the founding of a new party but at the redefinition of political space. What is at issue is thus not simply new parliamentary political majorities but a transformation of the institutional framework.

The danger of accommodation to the institutions (as in the case of the German Greens, who in the end transformed themselves more than they did politics) has up to now been held at bay through the sheer speed of the movement's growth. The anti-institutional resistance is permeating the institutions with such vehemence that the institutions cannot hedge and absorb the dissidence – at least this is the project's manifest hope.

In this Podemos can certainly be accused of being itself a result of ‘alienated‘ politics. The comparison with the Guanyem initiative in Barcelona makes it clear what this means: The latter is committed – completely within the logic of grassroots movements – to local processes of change from below. Guanyem Barcelona, which will very likely present ex-squatter Ada Colau as a candidate for the mayoral elections there, arose from the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH). The declared goal of Guanyem is to set into motion a municipal grassroots movement via municipal district assemblies, which will work out a platform for an alternative city government. It is thus expressly not aiming at welding together left groups through negotiations to form a coalition but to circumvent the existing (fragmented) left and at the same time incorporate them through the emergence of a grassroots movement. In terms of method, a path is being consciously taken here which is an alternative to the extant forms of representation.

Podemos is proceeding completely differently in this respect and has had great success – although in so doing it is in conflict with the radical-democratic postulates of 15M: Podemos’ founding group – Pablo Iglesias, Juan Carlos Monedero, Carolina Bescansa, Luís Alegre, and Íñigo Errejón – are Madrid political scientists, most of whom have worked for extended periods in Venezuela or in Bolivia. Its central figure is the 36-year-old Pablo Iglesias, who has made a name for himself on radio and television talk shows as a critic of the neoliberal regime.

The rise of Podemos thus does not completely conform to the grassroots criteria of the 15M Movement. The initiative is carried by a small group, which to be sure intends to subject itself to democratic contestation processes but at the same time has formulated a clear claim to leadership. And it is doubtless also a product of the mass media; without television Podemos would probably be a marginal phenomenon. The grassroots participatory process unfolding with Podemos was thus originally set in motion in a more vertical way.

Podemos’ founding group is pursuing a strategy overtly based on Latin American experiences. The central objective is to transform the general social discontent into an alternative political hegemony and thus launch a mobilization that in turn will open up perspectives going beyond a classic reform policy. In this context we should remember that the political change in Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia was neither the simple result of electoral victories nor the result of revolutions but emerged from the combination of radical rupture, continuity, and transformation. The anti-neoliberal revolts and mass uprising have blocked the neoliberal regime in these countries for almost a decade, but the regime change took place within the existing political system. The opening up of larger transformational perspectives after this was in the last analysis due to the constitutional processes that gave form to the underlying constituent processes (the emergence of alternative popular power). These constitutional processes resulted from the fact that in these countries there was broad popular participation in the discussion of a new social contract. Podemos appears to be pursuing a similar project; it is formulating, at least implicitly, the problem of a democratic revolution that bursts the existing institutions.

Two Elements of Discourse

To open up this possibility Podemos’ discourse is based principally on two elements. 1. Relative Indeterminacy: Even if its critique of neoliberalism is unequivocal the consequences drawn from it are indefinite. Podemos’ whole presence appears shaped by this ambivalence. Although its founding circle comes out of the Communist Youth, was active in the milieu of the Izquierda Unida (IU – United Left) or the more left Izquierda Anticapitalista, or positively refers to Chavism in Venezuela, Podemos tries to position itself outside of left-right schemes. Time and again, Podemos stresses that it represents ‘the new’, which cannot be described by concepts linked to ‘the old’. Accordingly, social conflicts are not dealt with as class questions but as a conflict between los de abajo, those ‘at the bottom’ (to which then the ominous ‘middle strata’ explicitly belong, which are becoming increasingly scarce in Spain), and the ‘political caste’. All problems which could damage the ‘Podemos brand’ – in the marketing newspeak that the founders themselves use in describing the party – are dealt with in a similarly ambiguous way. For example, Iglesias positively approaches the concept of patriotism, a concept heavily tainted in Spain, and re-signifies it: “Being a patriot means extending the democratic right to self-determination to all spheres and defending the public services.” At the same time, however, he defends the right of Catalans and the Basque to decide whether they want to belong to Spain, even though he regards independence as not a sensible solution.

2. Momentum: Podemos assumes that the weakness of left politics is not due to faulty analysis but to the lack of a promising counter-project, and as a consequence is committed to targeted political mobilization. The entire political energy is to be concentrated on overthrowing the two-party system, that is, ‘the caste’, in the 2015 elections. This purpose is expressed with a conviction that at times sounds bizarre – now the party is even striving for an absolute majority ‘because there is no alternative to it’.

Against this background it becomes clear why it does not make sense to acuse Podemos of the ambiguity we have described. Podemos has kept its discourse open in a completely conscious way. They are openly building here on the experiences of the constituent processes in Latin America. In the 1990s and 2000s, Latin America's neo-left, especially Venezuelan Chavism, developed discourse figures capable of achieving hegemony (without working through them on the level of theory), which Ernesto Laclau later called “empty signifiers.” Laclau claims that hegemonic politics necessarily implies vagueness because social relations are heterogeneous and projects capable of majority support must accordingly reflect this heterogeneity through ambiguity. Moreover, the relative indeterminacy of a project opens up, to ‘the many’, participatory and democratic space for shaping reality. In the end, a social transformation is only truly open if the result is not predetermined at the outset. Podemos seems to have internalized these considerations. The project's main objective is to open a political space to the social majorities excluded from the real decision-making processes. Just as Chavism, which first attacked the corrupt ‘Fourth Republic’ as enemies and then the ‘escuálidos’, that is, the U.S.-oriented elites, Podemos has similarly chosen a clearly defined, rhetorically easy to handle opponent that unites the heterogeneous popular camp through exclusion: ‘the caste’.

The dangers of this radical political experiment are obvious. That the indeterminacy of the project has up to now not found expression in turf wars is also due to the fact that all efforts are being concentrated on overthrowing the two-party system. As soon as this goal is achieved or setbacks are suffered along the way, this openness can lead to a crisis at any moment. At least Podemos’ base is more heterogeneous than that of Germany's Pirates: The European Parliament deputy Pablo Echenique, who proposed an alternative, more collective organizational structure at Podemos’ founding congress, recently admitted, with admirable self-criticism, that just a few years ago he had been a supporter of the neoliberal party Ciutadans and had been in favour of the Iraq War. Other Podemos components had been apolitical, internet activists or were active in the Communist Youth.

The danger is also very real that the founding group will become an elitist leadership circle. The new organizational statute, which was discussed in October in the Asamblea di Ciudadanos and then approved in a rank-and-file decision, strongly reduces the party's structure to the leader, Pablo Iglesias. The alternative draft, “Sumando Podemos,” submitted by the European Parliament deputies Pablo Echenique and Teresa Rodríguez, proposed a three-person collective leadership. It makes sense that the overwhelming majority were for Iglesias’ concept; precisely because Podemos is so heterogeneous the organization needs a strong symbolic identity. Furthermore, in recent years Iglesias has acted coherently and with ethical integrity – and he is therefore capable of integrating diverse currents.

On the other hand, in the process a personalistic leadership structure is being established, which – as can be observed in the last decade in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador – can, it is true, facilitate social mobilization but which then at its core contradicts longer-term democratization processes. Very strong leadership figures foster a culture of opportunism and claqueurs.

Long-term Transformation Project?

But the central question is a different one: Does Podemos actually have a transformation project that goes beyond the removal of the Partido Popular (PP) government? I think it does. For what would have to be done has been obvious after the mobilizations since 2011 and the ongoing conflicts with the other nations in the Spanish state:

Finally, there is the question of why IU (Izquierda Unida – the United Left) was not able to articulate these wishes for change, although it shares many of Podemos’ demands and in some cases formulates them more clearly. The answer seems obvious to me: IU could not articulate the revolt against the political system because it itself was an integral part of this system in many respects. The Communist Party (CP) – as the most important party of IU – actively backed the 1978 constitutional pact and also participated, via the trade union Comisiones Obreras, in the social partnership, established by the PSOE, with all its corporatist practices. IU, as a broad electoral alliance, has repeatedly formed coalition governments with the PSOE and in so doing also reproduced the usual corrupt practices. It participated – as, for example, in the case of the Caja Madrid savings bank – in the plundering of public financial institutions.

But even apart from the question of individual cases of corruption IU's organizational structures stand in contradiction to the radical democratic ambitions emerging from society. The political practice of the CP and IU was always marked by the classical logic of representation in which priority is given to the strengthening of one's own organization and its electoral successes over social (self-empowerment) processes. The means to this change – the political organization – has become an end in itself, so that IU, like almost all parties belonging to the Party of the European Left, has become a self-referential electoral alliance. Even if thousands of party members are active in movements, the institutional logic dominates. Radical attempts at reorganization come too late.

Podemos has – up to now – been different: The organization is presently the instrument of a social process that is progressing too rapidly for the party to turn around the relation between the democratic revolt and the institutional form.

This of course does not mean that everything that happened in IU or was done by it in the last thirty years was wrong. Podemos will probably soon be confronted by many of the problems that characterize IU today. For example, how can a balance be found between the emerging political tendencies without internal organizational considerations determining the politics of the organization. But this is probably the central insight of the political process in Spain today: The intervention of the organized left was not at all irrelevant; without the experience of left activists, the 15M Movement would have fallen apart sooner, the PAH never have emerged, and Podemos would probably have been a diffuse liberal internet party like Germany's Pirates. However, a social process is sweeping aside even the organizational forms of the left. The revolutionary-democratic awakening, longed for by a part of Spanish society, cannot be articulated through the bureaucratic corset of the IU. How long Podemos remains the appropriate space for this is to be seen. However, today Podemos is one of the spaces of the democratic revolution in Spain and probably the most important one. •

[Raul Zelik is a freelance writer and currently a Fellow at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.]