South Africa: Marikana massacre – a turning point?

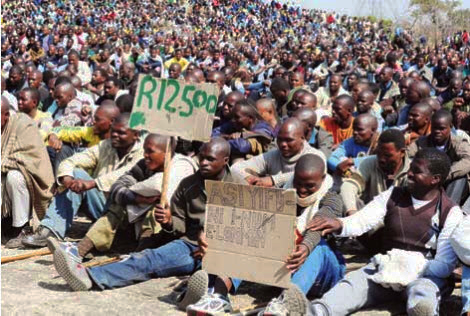

Marikana mineworkers on strike for higher pay.

For more coverage of South Africa, click HERE.

By Martin Legassick

August 27, 2012 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal -- The massacre of 34, and almost certainly more, striking mineworkers at Marikana (together with more than 80 injured) on August 16 has sent waves of shock and anger across South Africa, rippling around the world. It could prove a decisive turning point in our country’s post-apartheid history.

Marikana is a town situated in barren veld, dry brown grass in the winter, with occasional rocky outcrops (kopjes, hillocks). The Lonmin-owned mines – there are three, Karee, West and East Platinum – are situated on the outskirts of the town. Alongside two of them is a settlement of zinc-walled shacks festooned with lines of washing called Enkanini, where most of the mineworkers live.

Towering over the shack settlement are the surface buildings of the mine, together with a huge electricity substation, with giant power pylons marching across the veld. This is the mineral-energy complex that has dominated the South African economy since the 1890s, basing itself on the exploitation of cheap black migrant labour. But now platinum has replaced gold as the core of it.

South Africa produces three-quarters of the world’s platinum (used for catalytic converters in cars and for jewellery) and has dropped from first to fifth in production of gold. The underground workers at Marikana are still predominantly from the Eastern Cape, the area most ravaged by the apartheid migrant labour system. One third are contract workers, employed by labour brokers for the mines, with lower wages and no medical, pensions or benefits.

Platinum rock drillers work underground in temperatures of 40-45 degrees Celsius, in cramped, damp, poorly ventilated areas where rocks fall daily. They risk death every time they go down the shafts. At Marikana, 3000 mineworkers were and are striking for a wage increase from R4000 to R12,500 a month.

The juxtaposition of the mineral-energy complex with Enkanini, where outside toilets are shared among 50 people, where there are a few taps that will only trickle water, where raw sewage spreading disease leaks from burst pipes, and children scavenge on rubbish dumps, is symptomatic of the huge inequalities in South African society today. (More details on living conditions can be found in “Communities in the Platinum Minefields: Policy Gap 6” at http://www.bench-mark.org.za).

Inequality has increased since 1994 under the post-apartheid African National Congress (ANC) government. CEOs earn millions of rands in salaries and bonuses while nearly one-third of our people live on R432 rand a month or less. The top three managers at Lonmin earned R44.6 million in 2011 (Sunday Independent, August 26, 2012). Since 1994 some black people have been brought on board by white capital in a deal with the government – and they engage in conspicuous consumption.

Cyril Ramaphosa, former general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), who is now a director of Lonmin, recently bought a rare buffalo for R18 million, a fact contemptuously highlighted by Marikana workers when he donated R2 million for their funeral expenses. Unemployment in South Africa, realistically, is 35-40% and higher among women and youth; the highest in the world.

Shot while trying to escape

The media have highlighted police shooting automatic weapons at striking mineworkers running towards them from the rocky kopje where they were camped, and bodies falling to the ground dead. The police had erected a line of razor wire, with a five-metre gap in it, through which some mineworkers were attempting to return to Enkanini to escape tear gas and water cannon directed at them from behind.

Researchers from the University of Johannesburg (not journalists, to their shame) have revealed that the most killing did not take place there. Most strikers had dispersed in the opposite direction from Enkanini, trying to escape the police. At a kopje situated behind the hill camp there are remnants of pools of blood. Police markers in yellow paint on this “killing kopje” show where corpses were removed: there are labels with letters at least up to “J”. Shots were fired from helicopters to kill other escaping workers, and some strikers, mineworkers report, were crushed by police Nyalas (armoured vehicles). Within days police swept the whole area clean of rubber bullets, bullet casings and tear-gas canisters. Only patches of burned grass are visible, the remains of police fires used to obscure evidence of deaths.

There are still workers missing, unaccounted for in official body counts. The death toll is almost certainly higher than 34.

The cumulative evidence is that this was not panicky police firing at workers they believed were about to attack them with machetes and sticks. Why otherwise leave a narrow gap in the razor wire? Why kill workers running away from the police lines? It was premeditated murder by a militarised police force to crush the strike, which must have been ordered from higher up the chain of command. It has recently been reported that autopsies reveal that most of the workers were shot in the back, confirmation that they were mowed down by the police while escaping.

Because of the global capitalist crisis, with a slump in demand for new cars, the price of platinum has been falling, squeezing Lonmin’s high profits. Lonmin refused to negotiate with the striking mineworkers, and instead threatened mass dismissals, a favourite weapon of mining bosses. They were losing 2500 ounces of platinum output a day, amounting to more than $3.5 million. It was in Lonmin’s interest to smash the strike. A platinum CEO is quoted as saying that if the R12,500 demand was won, “the entire platinum mining sector will be forced to shut down” (New Age, August 20, 2012).

But the massacre has rebounded in their face. It has reinforced the anger and determination of the Marikana mineworkers to continue striking. “We will die rather than give up our demand”, said one at a protest meeting in Johannesburg on August 22. Moreover, since the massacre, workers at Royal BaFokeng Platinum and Anglo American Platinum have joined the strike. A general strike in the platinum industry is not ruled out.

The police chief, Riah Phiyega, visited police in Marikana in the days before the massacre. On the day of the massacre a police spokesperson declared, “Today is unfortunately D-day” (Business Report, August 17, 2012). After the killings Phiyega said, “It was the right thing to do” (The Star, August 20, 2012). The ANC government is implicated in these murders – in defence of white mining capital.

ANC-police orchestrated violence

The massacre is part of a pattern of ANC-police orchestrated violence against social protest, for example against Abahlali baseMjondolo in Kennedy Road in Durban in 2008-9 and in Umlazi recently, and which has resulted in the killing of Tebego Mkhoza in Harrismith, of Monica Ngcobo in Umlazi, of Andries Tatane in Ficksburg and South African Municipal Workers Union (SAMWU) leader Petros Msiza last year, to name but a few.

Certainly the Marikana massacre has severely damaged the moral authority that the ANC inherited from the liberation struggle. Since August 16, South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma has gone out of his way to distance himself from the killings. He has deplored the tragedy, visited the site six days later – to a cool reception from the mineworkers – declared a week of mourning and established a commission of enquiry.

He is hoping to restore the image of the ANC and of himself before he has to face re-election at an ANC conference in Mangaung in December. The commission has five months to report – which he hopes will cover up discussion of the events until after Mangaung. “Wait for the report before making a judgement” will be the watchword of the ANC and its allies in the next months.

Suspicious of the official commission, the mineworkers have called for an independent commission of enquiry, and the dropping of charges against 259 workers who have been arrested. “The same person who gave the order to shoot is the one who appointed the commission”, said a worker (Business Day, August 23, 2012).

Expelled former ANC Youth League president, the populist Julius Malema, has taken advantage of the massacre to visit Marikana, denounce Zuma and give assistance to the dead mineworkers’ families. Also all leaders of the parliamentary opposition went as a delegation to a meeting in Marikana on August 20 to offer condolences – like flies hovering around a dead body. At the same meeting a procession of 20 or more priests each sought to claim the loud hailer.

Union rivalry?

The mass media have claimed that the violence was precipitated by rivalry between the NUM and the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). This is nonsense. When the Marikana rock drillers went on strike they wanted to negotiate directly with management, not to have any union represent them. This was made absolutely clear at post-massacre meetings in Marikana, and at the protest meeting on August 22.

The strike was violent. In the week before the massacre 10 people died, six mineworkers, two mine security guards and two policemen.

Historically, the National Union of Mineworkers, born in the struggle against apartheid, has represented mineworkers. It has a proud history of struggle, including the 1987 mineworkers’ strike, led by Cyril Ramaphosa. But since 1994 it has increasingly colluded with the bosses. At Lonmin it had a two-year wage agreement for 8-10% annual increases.

When the rock drillers struck for more than doubled wages, NUM tried to prevent them. The strikers assert that the NUM was responsible for the death of two of mineworkers early in the strike. Two days before the massacre NUM general secretary Frans Baleni stated of the strikers, “This is a criminal element” (Business Report, August 15, 2012). Since the massacre Baleni has claimed it was “regrettable” but he has not condemned the police, only “dark forces misleading the workers” (see the video on the NUM website). Baleni earns R77,000 a month, more than 10 times what the rock drillers earn. NUM members in Marikana have torn up and thrown away their union T-shirts. At the Johannesburg protest meeting on August 22 an NUM speaker was shouted down by Marikana mineworkers.

The beneficiary is the AMCU, which before the strike had only 7000 members at Karee, a part of the Marikana mine where workers did not strike. (Its membership there was drawn in by a disaffected NUM branch leader after a strike last year.) Now workers from West and East Platinum are joining the AMCU.

The AMCU was formed after 1999 when its present president, Joseph Mathunjwa, was dismissed by a coal mine in Mpumalanga and reinstated because of workers’ protest, but then faced a disciplinary hearing from NUM for ‘bringing the union into disrepute”. He was expelled by the NUM (whose general secretary, ironically, was then Gwede Mantashe, now general secretary of the ANC) and formed the AMCU.

Today the AMCU claims a membership of some 30,000. It represents workers at coal, chrome and platinum mines in Mpumalanga, and coal mines in KwaZulu-Natal. It has members at chrome and platinum mines in Limpopo, and is recruiting at the iron ore and manganese mines around Kathu and Hotazel in the Northern Cape. It has focused on vulnerable contract workers. In February-March this year it gained membership in a six-week strike of 4300 workers (in which four people died) at the huge Impala Platinum in Rustenburg, a 14-shaft mining complex with 30,000 workers. At this stage it is unclear whether it can build a solid organisation for platinum workers, or merely indulge in populist rhetoric.

The AMCU is affiliated to the National Council of Trade Unions (NACTU), rival union federation to the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), both also born in the struggle against apartheid. COSATU, however, is allied with the ANC and is partly compromised by its relationship to government.

COSATU divisions

The platinum strikes and the Marikana massacre take place on the eve of COSATU’s 11th congress, to be held on September 17-19. COSATU has long differed with the ANC on economic policy, and in the recent period has been racked by internal differences over this and over whether or not Zuma should have a second term as ANC president and hence, after the 2014 election, remain president of the country. COSATU’s president Sdumo Dlamini, supported by the NUM and the National Health and Allied Workers’ Union (NEHAWU), supports Zuma. COSATU general-secretary Zwelinzima Vavi, together with the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) and the South African Municipal Workers Union (SAMWU), is less keen on Zuma’s re-election. Other unions are divided.

Vavi’s political report to the congress writes of “total state dysfunction” (concerning the failure of the ANC government to provide textbooks to Limpopo schools) and states there is “growing social distance between the leadership and the rank and file” of the ANC (Mail and Guardian, August 10-16, 2012).

At its June congress NUMSA passed resolutions on nationalisation of industry and declared “that nationalisation of the Reserve Bank, mines, land, strategic and monopoly industries without compensation must take place with speed, if we are to avoid sliding into anarchy and violence as a result of the cruel impact of ... poverty, unemployment and extreme inequalities in South Africa today”. Under workers’ control and management, this policy could rapidly end inequality and poverty in South Africa. (Julius Malema and the ANCYL also favour nationalisation of the mines, but this is interpreted as a desire to enrich predatory black businesspeople who could sell their assets to the state.)

The National Union of Mineworkers is less keen on nationalisation. “We are for nationalisation, but not a nationalisation that creates chaos”, said an NUM spokesperson recently. In a June document NUM criticised “populist demagoguery … calling for nationalisation as the solution to … challenges” such as socioeconomic conditions and failures by the mining industry to adhere to transformation or mining charter requirements (miningmx, August 19, 2012).

Vavi in his political report also drew attention to “a growing distance between leaders and members” within COSATU unions (Mail and Guardian, August 10-16, 2012) – which also applies to the NUM. Recently, the NUM general secretary in a private meeting with Vavi warned him to cease his “one-man crusade” or face being unseated at the COSATU congress.

Now the shock waves of the massacre will reverberate through the congress. The differences could be magnified, and some observers even predict that COSATU could split, either at or after the congress. Both factions of the COSATU leadership, however, are threatened by the erosion of the NUM and the growth of the AMCU and other unions attracting disgruntled COSATU members.

A COSATU statement (August 23, 2012) speaks of “a co-ordinated political strategy to use intimidation and violence, manipulated by disgruntled former union leaders, in a drive to create breakaway ‘unions’ and divide and weaken the trade union movement”. It says the COSATU congress will “have to discuss how we can defeat this attempt to divide and weaken the workers, how we can … cut the ground from under the feet of these bogus breakaway ‘unions’ and their political and financial backers”. The threat to workers’ unity is a powerful stick with which to temporarily re-unite the factions in COSATU. This strategy will be backed by the South African Communist Party (SACP), which is influential within COSATU. In reality, of course, it is the NUM leadership that is dividing the working class, through its failure to represent workers adequately, causing them to leave the union.

Were COSATU to split, were the AMCU and other dissident unions to link up with this split, favourable conditions would be created for the launching of a mass workers’ party on a left-wing program that could challenge the ANC for power. It would represent a combination of splits in traditional workers’ organisations and the emergence of new organisations. But this is not the most likely immediate scenario.

The consequences for Zuma at Mangaung are as yet unpredictable. They depend on how reaction to the massacre unfolds in the next months. Already it is reported that members of the ANC national executive are incensed at Zuma (Sunday Times, August 26, 2012). Unless the ANC can manage the situation successfully, the waves of shock and anger could catalyse the beginning of the end of ANC rule. Certainly, nothing will ever be the same again.

[Martin Legassick is active in housing issues in the Western Cape and a member of the Democratic Left Front, an anti-capitalist united front. He visited Marikana in the aftermath of the massacre.]

Being Pedantic

Just a pedantic note. "Kopje" is Dutch, not Afrikaans. People in SA don't actually speak Dutch. My non-South African dictionary on my phone actually contains the word "Koppie" and not the word "Kopje".

Other than that...WOW, the white man is at it again. No, wait...

Yea, people are people. It does not matter what colour is in control, those in power will at some point do what they do :(

Marikana: common purpose charge a travesty of justice

30 August 2012

The Democratic Left Front (DLF) is shocked, disgusted and angered by the decision of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to charge the 270 workers from the Lonmin platinum mine in Marikana currently in custody with the murder of their 34 fellow workers, comrades and strikers who were callously mowed down by the South African Police Service on 16 August 2012.

The NPA has the audacity to justify this decision on the basis of the common law doctrine of common purpose where “suspects with guns or any weapons and they confront or attack the police and a shooting takes place and there are fatalities” (as stated to the BBC by an NPA spokesperson, Frank Lesenyego). Infamously, the common purpose charge was last used in a high profile case by the apartheid regime with the Upington 6 case. So much for all the last week's meaningless platitudes and crocodile tears over the Lonmin massacre from the ANC and government!

Clearly, President Zuma’s Judicial Commission of inquiry has been rendered irrelevant by this charge. Why waste money on a Judicial Commission when the state has already decided that the workers are responsible for having themselves shot at and their comrades killed by the police? What a travesty of justice! This amounts to cynical cruelty and a flagrant contempt for truth. This opens the door to an official cover-up of the publicly witnessed shooting of the striking workers by the police. Already, there has been wanton destruction of evidence at the crime scene. All this, together with today’s problematic decision of the Garankuwa Magistrate’s Court to grant the State permission to postpone the bail application of the workers for another 7 days. These workers have been in jail for more than 15 days. All this militates against a fair trial of these workers.

On the basis of a doctrine of common affront, and solidarity, the DLF calls on all people in South Africa who stand for the truth and social justice to all line up at police stations demanding to be charged with murder. We call for this action for Thursday, 06 September when the arrested workers next appear in court.

The DLF calls on the NPA to withdraw the charges of common purpose against the Lonmin workers. The DLF calls on the NPA to lay charges of murder against the police. We say no to a police cover-up. We say no to a Judicial Commission of Enquiry that will whitewash the police.

More Marikana analysis & background

Marikana aftermath – Union leaders caught between a Rock and a Hard place

2012-08-26 ]

The killed miners were the victims of a black bourgeoisie who have sold out to the interests of white capital, write Martin Jansen and Mziwamadoda Velapi

The massacre of the Lonmin miners is likely to be another political turning point in the class struggle in South Africa.

Apartheid capitalism and white minority rule rested firmly on the super-exploitation of black mine workers and labour in general.

To preserve the system, any threat by workers was met with bloody brutality and deaths, meted out by mine security, the police and even the state’s army.

During the 1987 mine workers’ strike, then National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) general secretary Cyril Ramaphosa stated: “I don’t know how one shares power with people who have shotguns in their hands, people who have tear gas canisters, and I really don’t know how one shares power with people who continue to pay starvation wages.”

This was in response to the then Anglo Ashanti chief executive Bobby Godsell’s statement about the need for liberal business to share power with black workers.

The 1987 strike involved more than 300 000 miners, 50 000 of whom were dismissed and 10 lost their lives.

Now blood has been spilt once more and this time Cyril Ramaphosa and the former NUM president who led the 1987 strike, James Motlatsi, are mine bosses with shares in Lonmin through the Shanduka Group.

Over the years, under the initial leadership of Ramaphosa, the NUM has developed a very effective leadership cabal that became a conduit for a small powerful group within the new black elite to climb the social and political ladder – from mine workers’ leaders and union fat cats to political and capitalist bosses.

The treacherous role of the NUM leadership in the Lonmin strike is therefore not accidental.

Cyril Ramaphosa, Kgalema Motlanthe and Gwede Mantashe all once held the position of NUM general secretary.

They also personify the ANC’s shift from a radical petit bourgeois nationalist liberation movement to a bourgeois nationalist ruling party that protects the interests of the black bourgeoisie that is tied up with the economically dominant white monopoly capitalists.

Politically, this new dispensation is held up by the structure and political glue of the tripartite alliance, but this government is emphatically pro-business.

It used taxpayers’ money to meddle in labour disputes in favour of the employer by literally smashing the Lonmin workers’ strike.

The best special reaction units, including Unit 432 that committed the massacre, was called in.

The massacre of the Lonmin workers should also be seen as part of an increased conservatism and repressive approach by the ruling party over the last decade in relation to the ordinary masses, political opposition and even within its own ranks.

There have been other examples, such as the brutal killing of protester Andries Tatane.

With South Africa’s black elite inextricably tied to and intertwined with white monopoly capital and the entire capitalist system that breeds ever-expanding poverty and inequality, in the context of a global economic crisis, repression is their only realistic means of preserving the status quo.

Much of the tension among mine workers has its roots in the discontent of rank-and-file workers with the NUM leadership.

The formation of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union and the consequent inter-union rivalry has its roots in the high-handedness of the leadership and the lack of genuine democracy in NUM.

Over many years, NUM has failed to represent the real interests of their members and not fought vigorously to fundamentally improve the conditions of most mine workers.

So it, and gradually several other trade unions in South Africa, have become corporatised with top officials earning the salaries of company directors.

Most of our trade unions are no longer genuine fighting organisations of impoverished workers, but instead serve as a useful buffer for the bosses, managing workers’ aspirations and demands, and even policing them.

It is imperative that our unions return to the unwavering universal trade union principles of unity, independence (both organisational and political) and internal democracy.

][Jansen and Velapi work for Workers’ World Media Productions as director/editor and journalist/radio producer respectively.]

Marikana aftermath – Outrageous claims or outrageous order?

2012-08-26Andries Bezuidenhout, Crispen Chinguno and Karl von Holdt

Andries Bezuidenhout, Crispen Chinguno and Karl von Holdt make sense of the violent mayhem at Marikana

The massacre at Lonmin’s Marikana mine evoked memories of apartheid-era police brutality.

How can this be explained?

Two factors are related to the platinum-area institutional failure:

» Industrial relations institutions centred on collective bargaining are unable to contain conflict in the context of the social dislocations and gross inequalities of the booming platinum mining region; and

» Weak local government institutions on the platinum belt are failing in developing orderly communal life.

This creates the context for violent practices to emerge as legitimate and normal ways to establish order.

During the 1922 Rand Revolt by white miners, snipers assassinated “scabs”, or strike breakers, from the top of Johannesburg’s mine dumps, strikers dug trenches and used municipal ablutions facilities as ammunition dumps.

The army bombarded strikers and towards the end of the strike then prime minister Jan Smuts sent in the air force to quell the revolt.

The answer to avoiding further violence was to institutionalise the conflict. Centralised collective bargaining was allowed for white miners, but black South Africans were excluded from the system.

In 1946, a strike led by the African Mineworkers’ Union was violently put down by the state.

Towards the end of the 1970s, conflict between various groups of workers had become so endemic the industry again saw the need for institutionalisation through collective bargaining.

Anglo American created space for union organisation, which saw the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) emerge in 1982.

Now, collective bargaining in coal and gold mines happens on a regular basis in the Chamber of Mines.

In platinum, however, the NUM negotiates with companies at a decentralised level.

At Impala, strikers forced an increase in remuneration for rock-drill operators to R9000 a month, while some operators at Lonmin were still paid R4 000 a month.

At Impala Platinum, the strike started with operators demanding a wage adjustment outside the bargaining unit, following a similar award to miners with blasting certificates.

From the onset, they rejected NUM involvement and set up interim committees instead. They alleged the NUM had been co-opted by management. Most of the NUM’s branch leaders are now drawn from job categories that were previously dominated by white miners.

Despite their strategic role, rock-drill operators feel alienated and disregarded as uneducated, cheap and unskilled.

The NUM uses English and other local languages in meetings, while the rock-drill operators are sceptical of the educated and English speakers.

They use Fanakalo, which they see as a language of unity among workers.

This division between leadership and membership presented unprecedented opportunities to rival unions and the Association of Mining and Construction Union moved in.

Managers and the NUM tried to convince workers to abandon the strike, but the new committee dismissed the NUM’s agreements and standing rules, and seemed reluctant to enter into new institutional arrangements.

One of their slogans is: “We don’t talk of percentages, but money.”

This is sustained by violence.

At Impala they demanded the resignation of two managers and threatened to kill them if challenged.

The skill levels of black workers have broadened and some have moved into the suburbs, while the old hostel-based residential arrangements have fragmented.

There are now 36 informal settlements around Rustenburg, which the police are said to avoid.

The scene of the massacre is next to a sprawling informal settlement.

Frustrated strikers forge “solidarity” through the use of violence directed at strike breakers.

The massive fire power unleashed by the police appears as an attempt to restore a crumbling industrial relations order based on an outrageous level of poverty and inequality.

These events are a sign of things to come, unless we find a new path of development.

[Bezuidenhout, Chinguno and Von Holdt are Gauteng-based academics involved with the Society, Work and Development Institute.]

Marikana aftermath – NUM Incorporated

2012-08-26Loyiso Sidimba

Did the union giant take it’s eye off the ball to become corporate?

The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) is not afraid to do business with mining companies.

City Press can reveal the NUM’s property company, Numprop, is linked through housing projects to at least two mining houses, Xstrata and Harmony Gold.

This is despite the fact that the union explicitly states it does not invest in the sectors in which it organises to prevent conflicts of interest.

The NUM has two companies through which its investments are held: Numprop and the Mineworkers’ Investment Company (MIC). Both are owned by the NUM’s Mineworkers’ Investment Trust (MIT), in which its top officials are trustees.

The trust was established in 1995 “to improve the quality of life for its members and former members, and their dependants through investment opportunities”.

Numprop has a business relationship with Xstrata through the Tubatse Estate, a housing development in the Limpopo mining town of Burgersfort.

Numprop is the joint developer of the estate with Commercial South African Properties.

The project is believed to be worth R750 million.

Housing units at the Tubatse Estate will cost between R600?000 and R1.5?million.

Although Xstrata denies any involvement in the development, the MIT’s annual report for 2011 states that a tender “was issued by Xstrata in which we (Numprop) were short-listed”.

Xstrata’s Christopher Tsatsawane said the company did not have any involvement in the Tubatse Estate.

At its congress in May, the NUM named Xstrata as one of three candidates for the “global worst employer” award.

The NUM has been under fire in the wake of the Marikana massacre for its perceived close relationships with mining houses.

This is seen as one of the reasons behind the growth of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, NUM’s competitor on the platinum fields.

NUM general secretary Frans Baleni, who chairs the MIT, said that although the union prevented its entities from doing business in the mining industry, this did not preclude them from investing “upstream or downstream of the industry, where the NUM does not organise”.

“To prevent the inclusion of its various commercial entities from any association with mining would in effect bar these entities from undertaking any transactions, given how closely interlinked mining is with all sectors in the South African economy,” he told City Press.

On the MIT’s links with mine owners, Baleni said the trust cannot dictate the investment mandate of its partners. He reiterated that mining reaches all sectors of the economy.

“If we do not want any association with partners who invest in mining companies, then we would be very limited in terms of who we co-invest with,” Baleni reiterated.

He said the reason for Numprops’ involvement in housing developments in mining towns was to improve the lives of members.

The MIT had no reason to bar Numprop from doing business in the mining industry as this was its way of facilitating access to housing for mine workers, Baleni said.

Another Numprop partnership “in the pipeline” is with Harmony Gold to convert mine hostels into family units.

Numprop also intends to redevelop mining towns and has teamed up for this with Mzansi Investment Holdings.

The union says Numprop doesn’t make any profit, owing to poor funding.

The NUM revealed at its congress that it was investigating the possibility of the MIC taking over Numprop.

Numprop also wants to turn a Humansdorp, Eastern Cape, farm into a new RDP housing development.

The company provides the NUM with office accommodation and owns 10 properties valued at R74?million.

The union’s head office in downtown Johannesburg is owned by Numprop.

Two weeks ago, Numprop kicked out the correctional services department after it failed to pay about R1 million in rent.

Parole officers had to work in the streets after being evicted.

The MIC wants its investment portfolio to have a net asset value of R3 billion by next year and is targeting healthcare, renewable energy, property, retail and the telecommunications sector for future investments.

The MIC further has business relationships with several firms with mining interests.

Remgro, the MIC’s fellow shareholder in FirstRand, owns about 5% of Implala Platinum.

WDB Investment Holdings, the MIC’s empowerment partner in FirstRand and Masana Petroleum Solutions, has interests in Kalahari Resources and Anglo Inyosi Coal.

The NUM collected about R209 million from its 310 820 members in 2011.

- City Press

Emerging AMCU mine union favours competitive coexistence

By: Martin Creamer

Published: 6th June 2012

JOHANNESBURG (miningweekly.com) – The much-vilified emerging labour union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), says it is in favour of peaceful competitive coexistence with the dominant and long-standing National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and is totally opposed to union monopoly for itself or any other union.

AMCU president Joseph Mathunjwa, who called a media conference in Johannesburg on Wednesday to counter what he called a baseless smear campaign against the union, accuses NUM of monopolistic tendencies and says that AMCU, in contrast, regards competition as being as healthy for labour as it is for business.

Mathunjwa complains that NUM behaves as if it has a “veto to represent the working class”.

“There’s no such thing. We have to coexist,” the 47-year-old preacher’s son from KwaZulu-Natal says (also see attached video interview).

AMCU believes in competition because it highlights any shortfalls that may exist and enables the union to improve.

Accompanied by AMCU national treasurer Jimmy Gama, general secretary Jeffrey Mphahlele and national organiser Dumisani Nkalitshane, Mathunjwa strongly denied allegations of the union engaging in violence and using unlawful tactics to gain access to workplaces.

AMCU, which has 50 000 members compared with NUM’s 300 000-plus, receives an estimated R700 000 a month in membership fees.

“We do not believe in violence,” Mathunjwa says, adding that the union preaches adherance to the rule of law, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, embracing in particular the right to freedom of association, as set out in chapter two of the Labour Relations Act, No 66 of 1995.

Platinum major Lonmin CEO Ian Farmer announced recently that his platinum mining company has agreed to confer limited organisational rights on AMCU in order to reflect its membership position within the London- and Johannesburg-listed group.

Mathunjwa tells Mining Weekly Online that AMCU now has office facilities, full-time shop stewards and other rights at Lonmin’s Karee mine, where he says that his union has 5 000 members, which makes it the majority union.

“In fact, all other operations of Lonmin are coming to join AMCU and nobody is intimidating or coercing them,” he adds.

Karee was the scene of last year’s illegal strike that led to 8 000 mineworkers being dismissed and then largely rehired, and it was through the dismissal and rehiring process that the NUM lost membership to AMCU.

At JSE-listed coal-mining company Keaton Energy, both AMCU and NUM participate in the company’s bargaining unit.

“In fact, AMCU is our majority union and we’ve found that it’s no different to any other union arrangement,” MD Paul Miller tells Mining Weekly Online.

It is also the majority union at an African Rainbow Minerals operation and is conducting recruitment drives at Anglo American Platinum and Gold Fields.

At BHP Billiton Energy Coal’s Witbank operation, AMCU has an agreement with the predominantly white United Association of South Africa union , which was struck in order to secure an organisational right.

However, AMCU has not been able to obtain a recognition agreement at the troubled Impala Platinum mine in Rustenburg, where it says it now claims to have 15 000 members.

It is at Impala that NUM has a closed-shop agreement, which AMCU decries as monopolistic.

It has thus referred the matter to the Council for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) and is awaiting the set down date.

If it fails to obtain a recognition right at the CCMA, it will request a nonresolution right, which entitles it to embark on a legal, protected strike.

AMCU is currently also fighting Barberton Mines in the Labour Court for an organisational right.

Mathunjwa says that where AMCU has representation, it strives to make a difference in the lives of its members by negotiating better working conditions, including employee benefits, and it believes that it is more effective than NUM.

Where the two unions are in accord is in the call for the banning of the labour brokers, which Mathunjwa says results in mine workers earning less than R4 000 a month, which he bemoans as the average wage of mineworkers.

It is also most aggrieved at being cast as the villain in the many incidents that have surrounded this year’s prolonged strike at Impala, which it says has tarnished its name.

AMCU, which has opted for green apparel – “green represents life” – as opposed to NUM’s choice of red, says that it is apolitical and noncommunist.

It believes that the government should be allowed to implement its proposed youth wage subsidy and urges Mineral Resources Minister Susan Shabangu to prevent further loss of lives from illegal mining.

A member of the Salvation Army, Mathunjwa is a trumpeter who prides himself of being able to read music “very well”.

He estimates AMCU’s running costs at about R500 000 a month and says that his leadership style is to be transparent.

As with NUM, AMCU’s membership fee is 1% of a member's pay.

Joseph Mathunjwa

By: Martin Creamer

3rd August 2012

Joseph Mathunjwa

AMCU

Full Name: Joseph Mathunjwa

Position: President of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU)

Main Activity of the Organisation: AMCU is a trade union for the mining industry

Date and Place of Birth: Amatikulu, northern KwaZulu-Natal, May 26, 1965

Education: Matriculation, Ulundi

First Job: Laboratory attendant, Rand Coal, 1986

Size of First Pay Packet: R300 to R400 a month

Value of Revenue under Your Control: Revenue of about R700 000 a month and running costs of about R500 000 a month

Number of People under Your Leadership: 50 000

Leadership Style: Transparent

Personal Best Achievement: Coming up with a union that will encompass all walks of life, irrespective of political affiliations

Person Who Has Had The Biggest Influence on Your Life: My father, David Mathunjwa, who was a Christian preacher

What Has Had The Biggest Influence on Your Career: The plight of the working class

Person You Would Most Like to Meet: Martin Luther King’s family

Businessperson Who Has Impressed You Most: Bill Gates, because of his philanthropy in Africa

Philosophy of Life: Treat people as you like to be treated

Biggest Ever Opportunity: Leading people in the union movement

Biggest Ever Disappointment: Seeing people being retrenched without companies making an effort to save jobs. It is so sad. The first retrenchment that we fought through the Labour Court was at BHP Billiton in 2005 and we won the case– that was our starting point

Hope For the Future: To see people sharing in the wealth of the country

Favourite Reading: TD Jakes

Favourite TV Programme: Nature

Favourite Food/Drink: Pap en melk/coffee

Favourite Music: Gospel. I am a member of the Salvation Army and I play the trumpet and read music very well

Favourite Sport: Soccer

Hobbies: Music. In my spare, time I teach youngsters to read music

Car: I don’t have a personal car. The car I borrow from the union is a Toyota Fortuner

Pets: None

Miscellaneous Dislikes: None

Married: To Thuli

Children: Three children aged 18, 13 and 4

Clubs: Orlando Pirates locally and Chelsea Football Club overseas