Has the Anthropocene been canceled?

First published at Monthly Review.

Some 2.8 million years ago, the level of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere dropped, triggering an Ice Age. Since then, long-term changes in Earth’s orbit and tilt, called Milankovitch cycles, have produced global temperature swings every 100,000 years or so. In the glacial (cold) phases, kilometers-thick ice sheets covered most of the planet; in shorter interglacial (warm) periods, the ice retreated toward the poles. For the past 11,700 years, we have lived in an interglacial period that geologists call the Holocene Epoch.

Under normal circumstances, the glaciers and polar ice caps would now be slowly growing. As recent research shows, “if not for the effects of increasing CO2, glacial inception would reach a maximum rate within the next 11,000 years.”1 Instead of global heating, the Earth’s future would be global freezing, but only in the distant future.

However, as anyone even slightly aware of environmental issues knows, the world’s glaciers and ice caps are not expanding; they are shrinking — fast. Between 1994 and 2017, Earth lost 28 trillion tons of ice, and the rate of decline has increased by 57 percent since the 1990s.2 Even if greenhouse gas emissions are rapidly reduced, conditions preventing the return of continental ice sheets will likely persist for at least 50,000 years. If emissions do not stop, the ice will not be back for at least half a million years.3

In short, as a direct result of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity, the Ice Age has been canceled.

This is concrete proof of one of the most radical conclusions of twenty-first century science: “The earth has now left its natural geological epoch, the present interglacial state called the Holocene. Human activities have become so pervasive and profound that they rival the great forces of nature and are pushing the earth into planetary terra incognita.”4

The scientists who first reached that conclusion named the new epoch the Anthropocene. An overwhelming volume of evidence shows that a new stage in Earth system history has begun, one characterized by major changes to many aspects of the natural world, heading toward conditions that humans may not survive. They have shown that many of the largest changes are irreversible on any human timescale. They have dated the beginning of this radical transformation to the mid-twentieth century. They have also shown that physical records of the change can be seen in geological strata.

To any reasonable observer, the case is irrefutable. Yet, some prominent scientists deny that a qualitative change has taken place, and one of the world’s largest scientific organizations has voted against formal recognition of the new epoch. The research and debates that led to this perverse result help to illuminate the challenges facing scientists and ecosocialists in our time.

Earth System Science

During the 1970s and ’80s, increasing numbers of scientists came to the conclusion that traditional scientific methods focusing on local or regional issues were insufficient for understanding environmental problems — that Earth as a whole had entered a period of extreme crisis caused by human activity.

In 1972, for example, Barbara Ward and René Dubos wrote that “the two worlds of man—the biosphere of his inheritance, the technosphere of his creation — are out of balance, indeed potentially in deep conflict.” Earth faced “a crisis more sudden, more global, more inescapable, and more bewildering than any ever encountered by the human species and one which will take decisive shape within the life span of children who are already born.”5

Several bestselling books by James Lovelock promoted what he called the “Gaia hypothesis” — that living matter actively regulates the planetary environment to ensure optimal conditions that sustain life. His views were rejected by most scientists, but their popularity encouraged study of the planet as a whole. Some scientists still use the word Gaia as a synonym for the Earth System.6

NASA formed an Earth System Sciences Committee in 1983, declaring that its goal was “to obtain a scientific understanding of the entire Earth System on a global scale by describing how its component parts and their interactions have evolved, how they function, and how they may be expected to continue to evolve on all time scales.”7 Millions of high-resolution images of Earth obtained by the Landsat satellites, first launched in 1972, contributed to that effort.

In 1986, the International Council of Scientific Unions approved the formation of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program (IGBP) “to describe and understand the interactive physical, chemical and biological processes that regulate the total Earth system, the unique environment that it provides for life, the changes that are occurring in this system, and the manner in which they are influenced by human activities.”8

The IGBP began operations in 1990, with a secretariat in Stockholm and a variety of international working groups that involved thousands of scientists. By any measure it was “the largest, most complex, and most ambitious program of international scientific cooperation ever to be organized.”9 For the next twenty-five years, the most important work in Earth System science was performed under the IGBP’s umbrella.

One of the IGBP’s founding statements began: “Mankind today is in an unprecedented position. In the span of a single human generation, the Earth’s life sustaining environment is expected to change more rapidly than it has over any comparable period of human history.”10 That statement proved more insightful than anyone imagined in 1990. In 2000, at a meeting where the various working groups reported on a decade of in-depth research, Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen concluded that the accumulated changes had broken through the limits of the present geological epoch. “We’re not in the Holocene anymore,” he declared. “We’re in the Anthropocene!”11

The importance of that insight cannot be overstated. Anthropocene was not just a new word, it was a new reality and a new way of thinking about the crisis of the Earth System. Several leading participants in the development of Earth System Science wrote recently:

ESS [Earth System Science], facilitated by its various tools and approaches, has introduced new concepts and theories that have altered our understanding of the Earth System, particularly the disproportionate role of humanity as a driver of change. The most influential concept is that of the Anthropocene, introduced by PJ Crutzen to describe the new geological epoch in which humans are the primary determinants of biospheric and climatic change. The Anthropocene has become an exceptionally powerful unifying concept that places climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution and other environmental issues, as well as social issues such as high consumption, growing inequalities and urbanization, within the same framework. Importantly, the Anthropocene is building the foundation for a deeper integration of the natural sciences, social sciences and humanities, and contributing to the development of sustainability science through research on the origins of the Anthropocene and its potential future trajectories.12

Crutzen initially suggested that the Anthropocene may have begun with the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s, but subsequent research focused attention on the middle of the twentieth century.

Key to this understanding was the discovery of a sharp upturn in a multitude of global socioeconomic indicators and Earth System trends at that time; a phenomenon termed the “Great Acceleration.” It coincides with massive increases in global human-consumed energy and shows the Earth System now on a trajectory far exceeding the earlier variability of the Holocene Epoch, and in some respects the entire Quaternary Period.13

In 2004, the IGBP published Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure, which synthesized the results of their research on global change and argued that “the Earth System is now in a no-analogue situation, best referred to as a new era in the geological history of earth, the Anthropocene.”14

After outlining what IGBP researchers had learned about the complex dynamics of the Earth System, the authors described how human activities are now changing it in fundamental ways. Their account included the famous “Great Acceleration” graphs, showing the unprecedented increases in economic activity and environmental destruction that began about 1950. The great metabolic cycles that support life on Earth—carbon, nitrogen, water, and more—were disrupted, and “the most rapid and pervasive shift in the human-environment relationship began.… Over the past 50 years, humans have changed the world’s ecosystems more rapidly and extensively than in any other comparable period in human history.”15

A new reign of climate chaos?

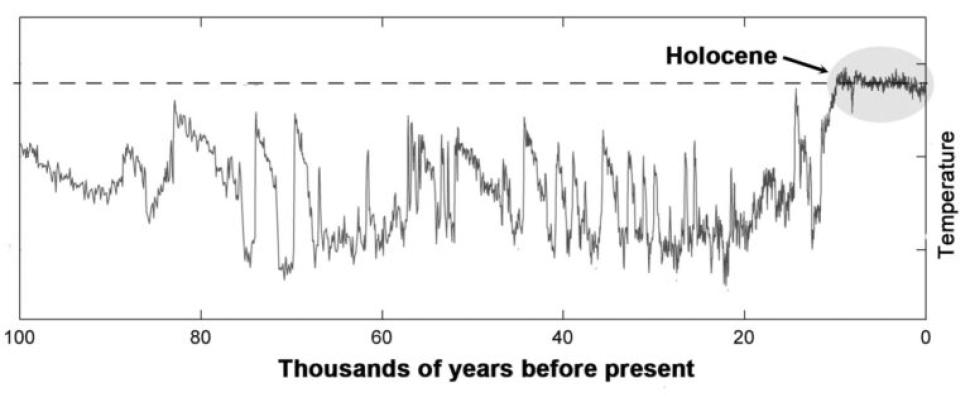

Chart 1, adapted from a study of ice-core data by scientists at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, shows the average annual temperature in Greenland over the past 100,000 years.16 The first 90 percent of this time was the end of the Pleistocene, a 2.6 million year-long epoch characterized by repeated glacial advances and retreats. In this period, the global climate was not only cold, it was in general extremely variable.

Modern humans walked the earth for all the time shown in this graph, but until the Holocene they lived in small, nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers. Climate historian William J. Burroughs, who calls the time before the Holocene the “reign of chaos,” compellingly argues that so long as rapid and chaotic climate change continued, agriculture and settled life were impossible. To succeed, agriculture needs not just warm seasons, but a stable and predictable climate — and indeed, not long after the Holocene began, humans on five continents independently took up farming as their permanent way of life. “Once the climate had settled down into a form that is in many ways recognizable today, all the trappings of our subsequent development (agriculture, cities, trade, etc.) were able to flourish.”17

The Holocene has been one of the longest stable warm periods in the last half a million years.18 From 11,700 years ago to the twentieth century, the average global temperature did not vary by more than one degree Celsius — up or down half a degree. That is not to say that Holocene weather was without extremes: the one-degree average variation included droughts, famines, heat waves, cold snaps, and intense storms. But overall, it was marked by a not-too hot, not-too cold, “Goldilocks” climate.

In 2009, twenty-nine leading Earth System scientists defined nine planetary boundaries that, if crossed, could destabilize the Earth System. Staying within the boundaries would maintain Holocene-like conditions, the only environment that we know for sure can support large and complex human societies. The most recent update, published in 2023, found that six of the nine boundaries have been crossed. The Earth System has left the safe operating space for climate change, biosphere integrity, land system change, freshwater change, biogeochemical (nitrogen and phosphorus) flows, and novel entities, and it is close to the boundary for ocean acidification. These shifts portend a climate that is hotter, more variable, and less predictable than any settled human society has experienced — a new reign of chaos.

Rarely has a new scientific concept won wide support as quickly as the Anthropocene. The decade following Crutzen’s spontaneous declaration produced a large body of Earth System research exploring aspects of the concept. An inflection point occurred in 2012, when the IGBP and other Earth System science organizations held a conference on global change in London. More than three thousand people attended in person and three thousand more attended online. The meeting’s final declaration was unequivocal:

Research now demonstrates that the continued functioning of the Earth system as it has supported the well-being of human civilization in recent centuries is at risk. Without urgent action, we could face threats to water, food, biodiversity and other critical resources: these threats risk intensifying economic, ecological and social crises, creating the potential for a humanitarian emergency on a global scale….

Humanity’s impact on the Earth system has become comparable to planetary-scale geological processes such as ice ages. Consensus is growing that we have driven the planet into a new epoch, the Anthropocene, in which many Earth-system processes and the living fabric of ecosystems are now dominated by human activities. That the Earth has experienced large-scale, abrupt changes in the past indicates that it could experience similar changes in the future. This recognition has led researchers to take the first step to identify planetary and regional thresholds and boundaries that, if crossed, could generate unacceptable environmental and social change.19

But geology…

Still, something was missing. “Holocene” is a geological term: it names the last 11,700 years, the most recent stage in the planet’s geological history. It is an epoch in the Geological Time Scale, which was created to ensure that all geologists have a common understanding of the stages of Earth’s physical history and use the same terms to describe it. Any change to the Geological Time Scale must be formally approved by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) and the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), both of which are notoriously conservative and resistant to change.

It was not until 2009 that the ICS asked palaeobiologist Jan Zalasiewicz of the United Kingdom’s Leicester University to chair a working group to investigate and report on whether geologists should formally recognize the Anthropocene as a new epoch.

The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) had to start from scratch: past working groups could base their deliberations on decades of existing research, but no one had yet looked for geological evidence of a break between the Holocene and a possible new epoch. In the years following the formation of the AWG, geologists around the world conducted dozens of research projects on that subject, with results published in peer-reviewed journals and in books edited by AWG members.

There was an immense amount of data and analysis to assimilate, especially since the group was small and its members were unpaid volunteers. However, by 2015 they had accumulated and evaluated a mass of geological evidence — strong physical indicators that a radical change was taking place. An article summarizing that evidence was published in the journal Science in January 2016.

The appearance of manufactured materials in sediments, including aluminum, plastics, and concrete, coincides with global spikes in fallout radionuclides and particulates from fossil fuel combustion. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles have been substantially modified over the past century. Rates of sea-level rise and the extent of human perturbation of the climate system exceed Late Holocene changes. Biotic changes include species invasions worldwide and accelerating rates of extinction. These combined signals render the Anthropocene stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene and earlier epochs….

The stratigraphic signatures described above are either entirely novel with respect to those found in the Holocene and preexisting epochs or quantitatively outside the range of variation of the proposed Holocene subdivisions. Furthermore, most proximate forcings of these signatures are currently accelerating. These distinctive attributes of the recent geological record support the formalization of the Anthropocene as a stratigraphic entity equivalent to other formally defined geological epochs. The boundary should therefore be placed following the procedures of the International Commission on Stratigraphy.20

By 2023, the AWG had decided, by an overwhelming majority, that a new geological epoch began in about 1950, and that the best stratigraphic signal for the beginning of the new epoch was the presence of plutonium isotopes, created and spread by the atmospheric hydrogen bomb tests that the United States and the Soviet Union conducted between 1952 and 1963.

Twelve locations on five continents were studied in detail for suitability as reference sites. The onset of the Anthropocene could be clearly identified in all twelve, but the researchers selected Crawford Lake in southwestern Ontario as the best location for a “golden spike.” For centuries, unique conditions there have preserved annual layers of sediment, including undisturbed layers containing plutonium. Three other locations, in Japan, China, and Poland, were selected as auxiliary sites.

Opposition

The most common argument against the new epoch was that human beings have always changed the environment, so the Anthropocene is nothing new. Late in the debate, this argument took the form of a proposal that the Anthropocene should be considered as an informal “event,” spread over thousands of years. In that framework, the Great Acceleration was at most an intensification of long-term continuing changes, not a qualitative shift.21

AWG members replied: “the Anthropocene is de facto a new epoch, not an encapsulation of all anthropogenic impacts in Earth history.” Indeed, that idea “runs counter to the Anthropocene’s central meaning” by extending it to all human-induced changes over thousands of years and ignoring “the abrupt human-driven shift a new Earth System state that has exceeded the natural variability of the Holocene.”22

In short, the proposal preserved the word but erased its fundamental meaning and radical content.

Other arguments against formalizing the Anthropocene ranged from trivial (the name is not appropriate; the idea comes from outside geology; other epochs are longer) to insulting (this whole thing is just about getting publicity). In 2017, members of the AWG assembled the published arguments against the Anthropocene and prepared responses to each. The resulting article was polite and collegial but nonetheless devastating. It left the critics with no scientific basis for continued opposition.23

Yet, as Zalasiewicz later wrote: “neither this strengthened evidence base, nor further evidence subsequently gathered, did anything to diminish the outright opposition to the Anthropocene from a minority of AWG members and their colleagues.” He went on:

This suggested that this opposition and that of others in the ICS — the strong opposition of the highly influential ICS Chair, Stanley Finney, was a significant factor — even when responded to and countered was not based on the amount and quality of stratigraphic evidence. Rather, it seemed to reflect more deep-seated aspects of the chronostratigraphically proposed Anthropocene….

Evidence-based refutations did nothing to prevent further reiterations of the “event” suggestion, again suggesting that the body of stratigraphic evidence assembled by the AWG was of little relevance to the central question of whether an Anthropocene epoch should exist at all.…

The Anthropocene clearly touches nerves that more ancient strata do not reach.24

In November 2023, when the AWG submitted its formal proposal to recognize the new epoch, it also submitted a complaint to the Geoethics Commission, charging that the executives of the ICS and the IUGS had deliberately hindered and undermined their work. The Commission reportedly supported the complaint and recommended that no vote be held. The IUGS appears to have ignored the recommendation.

If normal procedures had been followed, the AWG submission should have initiated a period of open discussion. Instead, in March 2024 the AWG’s proposal was abruptly voted down after a brief discussion in a closed-door setting. The IUGS did not reply to the AWG submission, it simply announced its rejection.

We can only speculate about the motives that led to this preposterous decision, but as archaeologists Todd Braje and Jon Erlandson have pointed out, this debate “has the potential to influence public opinions and policies related to critical issues such as climate change, extinctions, modern human-environmental interactions, population growth, and sustainability.”25 In that respect, it is surely relevant that geology — a science deeply implicated in the discovery and exploitation of fossil fuels — has been, shall we say, conservative on the question of climate change.

In 2016, the chair of the ICS charged that “the drive to officially recognize the Anthropocene may, in fact, be political rather than scientific.”26 The opposite seems more likely: opposition to the idea of the Anthropocene is political, not scientific. Certainly, he and his colleagues have ensured that no one can use the prestige of the ICS and IUGS in support of decisive action to prevent climate chaos. The price paid for that political win is a defeat for geology’s credibility — the Geological Time Scale no longer accurately reflects Earth history.

The AWG has not gone away. It continues operations as an independent group, and has published several important papers since the ICS and IUGS rulings.27 Like Charles Darwin in another time, they are challenging a scientific establishment that is bent on protecting an unscientific worldview — a difficult but essential contribution to the advancement of science.

Eight years before the top bureaucrats in organized geology made their decision, I closed a summary of Anthropocene debates with these words:

It is still possible that the usually conservative International Commission on Stratigraphy will either reject, or decide to defer, any decision on adding the Anthropocene to the geological time scale, but as the AWG majority writes, “the Anthropocene already has a robust geological basis, is in widespread use, and indeed is becoming a central, integrating concept in the consideration of global change.…”

In other words, failure to win a formal vote will not make the Anthropocene go away.28

Since I wrote that, the volume and persuasiveness of the evidence has only grown. The highest temperatures in human history, species extinctions on an unprecedented scale, a global glut of plastics and synthetic chemicals that nature cannot absorb, multiple pandemics of previously unknown diseases, and many more crises confirm that massive disruption of Earth’s life support systems is underway, in a new and deadlier stage of planetary history.

The Anthropocene may not be official, but it is real.

Ian Angus is editor of the online ecosocialist journal Climate & Capitalism and a founding member of the Global Ecosocialist Network. He is the author of Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System (2016) and, most recently, The War Against the Commons: Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism (2023), both published by Monthly Review Press.

- 1

Stephen Barker et al., “Distinct Roles for Precession, Obliquity, and Eccentricity in Pleistocene 100-kyr Glacial Cycles,” Science 387, no. 6737 (February 28, 2025).

- 2

Thomas Slater et al., “Review Article: Earth’s Ice Imbalance,” Cryosophere 15 (January 25, 2021): 233–46.

- 3

C. P. Summerhayes et al., “The Future Extent of the Anthropocene Epoch: A Synthesis,” Global and Planetary Change 242 (November 2024): 104568.

- 4

Will Steffen, Paul J. Crutzen, and John R. McNeill, “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?,” Ambio 36, no. 8 (December 2007): 614.

- 5

Barbara Ward and Rene Dubos, Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 12.

- 6

For a detailed scientific evaluation, see Toby Tyrrell, On Gaia: A Critical Investigation of the Relationship Between Life and Earth (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).

- 7

National Research Council, Earth System Science—Overview: A Program for Global Change (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1986), 4.

- 8

National Research Council, Global Environmental Change: Research Pathways for the Next Decade (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1999), 3.

- 9

Juan G. Roederer, “ICSU Gives Green Light to IGBP,” Eos 67, no. 41 (October 14, 1986): 777–81.

- 10

International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, IGBP Global Change: The Initial Core Projects, Report no. 12 (Stockholm: International Council of Scientific Unions,1990), 1–3.

- 11

I have described this process in more detail in the first chapter of Facing the Anthropocene (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2016).

- 12

Will Steffen et al., “The Emergence and Evolution of Earth System Science,” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (January 2020): 59.

- 13

Martin Head et al., “The Great Acceleration Is Real and Provides a Quantitative Basis for the Proposed Anthropocene Series/Epoch,” Episodes Journal of International Geoscience 45, no. 4 (December 2022): 359–76.

- 14

Will Steffen et al., Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure (New York: Springer, 2004), 93.

- 15

Steffen, Crutzen, and McNeill, “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?,” 617.

- 16

Andrey Ganopolski and Stefan Rahmstorf, “Rapid Changes of Glacial Climate Simulated in a Coupled Climate Model,” Nature 409 (January 11, 2001): 153–58.

- 17

William J. Burroughs, Climate Change in Prehistory: The End of the Reign of Chaos (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 13, 102.

- 18

J. R. Petit et al., “Climate and Atmospheric History of the Past 420,000 Years from the Vostok Ice Core, Antarctica,” Nature 399 (June 3, 1999): 429–36.

- 19

“Final Issues Statement from Planet Under Pressure Conference, London, 2012,” EarthSky, March 29, 2012, earthsky.org.

- 20

Colin N. Waters et al., “The Anthropocene Is Functionally and Stratigraphically Distinct from the Holocene,” Science 351, no. 6269 (2016).

- 21

Matthew Edgeworth et al., “The Anthropocene Is More Than a Time Interval,” Earth’s Future 12, July 18, 2024.

- 22

Jan Zalasiewicz et al., “Reply to Edgeworth et al. 2024: The Anthropocene Is a Time Interval, and More Besides,” ESS Open Archive, December 23, 2024.22

- 23

Jan Zalasiewicz et al., “Making the Case for a Formal Anthropocene Epoch: An Analysis of Ongoing Critiques,” Newsletters on Stratigraphy 50, no. 2 (April 2017): 205–26.

- 24

Jan Zalasiewicz, foreword to Martin Bohle, Boris Holzer, Leslie Sklair, and Fabienne Will, The Anthropocene Working Group and the Global Debate Around a New Geological Epoch (New York: Springer, 2025), ix, xii, xiv.

- 25

Todd J. Braje and Jon M. Erlandson, “Looking Forward, Looking Back: Humans, Anthropogenic Change, and the Anthropocene,” Anthropocene 4 (December 2013): 116–21.

- 26

Stanley C. Finney and Lucy E. Edwards, “The ‘Anthropocene’ Epoch: Scientific Decision or Political Statement?,” GSA Today 26, no. 3 (March 2016): 4–10.

- 27

Among others: Summerhayes et al., “The Future Extent of the Anthropocene Epoch”; Francine McCarthy Martin J. Head, Colin N. Waters, and Jan Zalasiewicz, “Would Adding the Anthropocene to the Geologic Time Scale Matter?” AGU Advances 6, no. 2 (February 2025); Mark Williams et al., “Palaeontological Signatures of the Anthropocene Are Distinct from Those of Previous Epochs,” Earth-Science Reviews 225 (August 2024): 104844.

- 28

Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, 58.