‘Beyond the Wall’: A objective look of the former German Democratic Republic

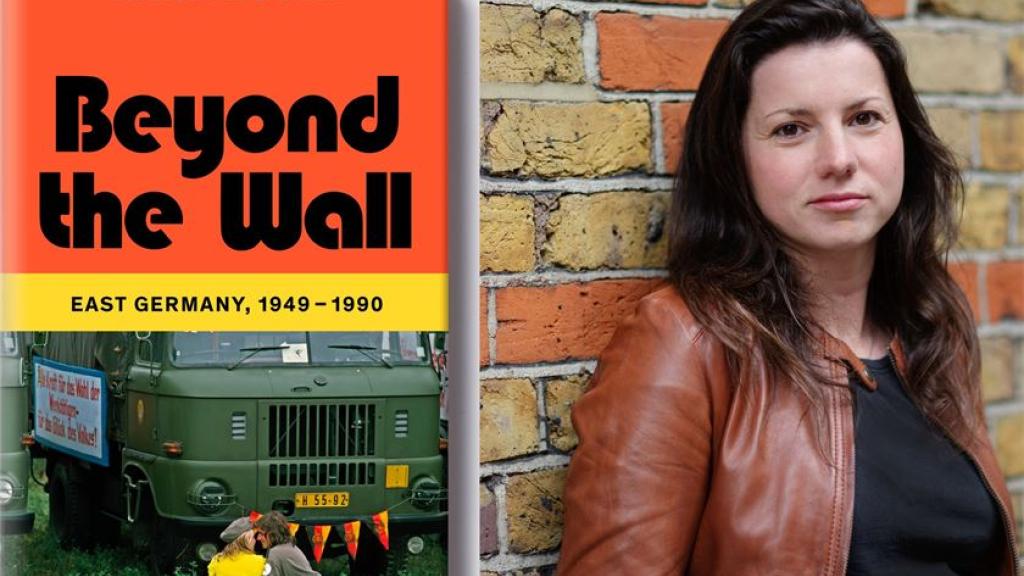

Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990

Katja Hoyer

Allen Lane, Dublin, 2023.

The common perception of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) is of a grim dictatorship in which miserable people lived in shabby tenements and drove funny little cars called Trabants. If there was anything good about the place, so the story goes, it was despite the worst efforts of the repressive Communist authorities. Moreover, the state’s failure and collapse is held to prove the superiority of capitalism over socialism. Not surprisingly, Katya Hoyer’s more balanced account has received a hostile reception from German establishment media. Hoyer is no apologist for the East German regime, but she has written a more objective history of the former state than they would like. She is not a socialist, but her book should be useful for socialists drawing the lessons from the collapse of what the Eastern Bloc rulers called “actually existing socialism”. Apart from this, Beyond the Wall is an absorbing read, which draws on interviews with people from a diverse range of backgrounds. As Hoyer told one journalist, “I wanted to get rid of the idea that the GDR was a grey country where people spent 40 years waiting for their liberation and did practically nothing else … A lot of stuff happened!”

The GDR had a short lifespan — a mere 40 years from its foundation in the chaotic aftermath of World War II to its sudden collapse and absorption by West Germany in 1989. Faced with a colossal task of reconstruction and with few natural resources any state of whatever political complexion would have struggled, yet by the 1970s its citizens enjoyed the highest living standards in the Eastern Bloc and many of them were reasonably content, even happy with their lives.

When the Nazi dictatorship fell in 1945, the victorious allies divided Germany into four occupation zones: the western sectors administered by Britain, France and the United States, and the eastern third by the USSR. The capital, Berlin, was split between the four powers. The Allies had also decided at the Potsdam Conference to amputate vast swathes of German territory in the east — East Prussia, Silesia, Pomerania and Danzig — and cede them to the Soviet Union and Poland. This alone deprived the eastern zone of most of its hinterland, together with essential raw materials and industry.

The future political and economic system of the vanquished nation was not cut and dried, and the idea of permanent partition was not raised. Stalin suggested that “the introduction of the Soviet system in Germany is wrong; what is necessary is the installation of an anti-fascist, democratic, parliamentary regime.” On the other hand, when the German Communist leader Walter Ulbricht returned from exile in Moscow, he believed that while there would be a democratic facade in the Eastern Zone, the Party would control the levers of power: in his own words, “It has to look democratic, but we must have everything in our hands.” Ulbricht had managed to survive the Stalinist purges of the 1930s and was determined to recast Germany in the image of the Soviet system. Stalin was not convinced, and as late as 1952 — that is after the foundation of the GDR in 1949 — he was prepared to throw his “brother socialist state” under a bus, proposing its incorporation in a united, neutral Germany, which would act as a buffer state to shield the Soviet Union from aggressive NATO expansion. Further, the re-unified state would be governed as a parliamentary democracy and the GDR’s post-capitalist economy would be sacrificed. Hoyer argues that although the proposal “is often brushed aside as a mere propaganda move … there are numerous documents that indicate Stalin was serious.” Indeed, although she does not explore the theoretical intricacies, the proposal was entirely in keeping with the Stalinist dogma of “socialism in one country”, which put the needs of the USSR and its rulers above those of the world revolution.

The GDR was thus expendable and in any case the German people had to be punished as many saw it allowing Hitler to embark on a genocidal war of conquest. Initially, under the Morgenthau Plan, the US planned to de-industrialise and demilitarise Germany — to turn it into a giant farm incapable of waging aggressive war. Stalin did not disagree, and although the Western Powers softened their position and back-peddled on the payment of reparations decided upon at Potsdam, Stalin stuck to his hard line. Hoyer summarises the immense reparations extracted from the Eastern Zone and the GDR thus:

Private looting and theft aside, the Soviets had officially taken reparations and compensation for occupation costs in excess of (US) $15 billion out of the GDR by 1953. This encompassed the wholesale dismantling of entire factories and other fixed assets as well as the sourcing of useful raw materials. Lead piping was ripped from walls, iron climbing frames stolen from playgrounds and entire train lines deconstructed and relaid in the Soviet Union. The GDR might have recovered from this eventually had it not been for the crippling scale of ongoing reparations that were literally taken from German assembly lines … In total, 60 per cent of ongoing East German production was taken out of the young state’s efforts to get back on its feet between 1945 and 1953.’

By 1953, when Stalin agreed to end the policy, “the GDR had paid three times as much in reparations as its Western counterpart”.

The infant state was almost throttled in its cradle by its “socialist brother nation”. On top of this, the GDR emerged in the poorest, least industrialised and most agrarian one-third of the shrunken German postwar territory. Because of the loss of territories beyond the Oder-Neisse line, the GDR lacked almost all of the raw materials necessary for a modern industrial state. Without black coal, oil, or large-scale hydro-power, it was forced to rely on lignite — poor quality brown coal — that was also a major pollutant. The GDR did have uranium, but it was shipped to the USSR. The US had ditched the Morgenthau Plan but arguably Stalin had adopted it.

Much is made, Hoyer tells us, of the West German “economic miracle” that saw the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) rise from the postwar ruins. This is often contrasted with the situation in the GDR, but we should not overlook the fact that the FRG had inherited most of the country’s industrial base and that reparations were much less onerous than in the East. In addition, West Germany benefited from just under US$1.4 billion in Marshall Plan aid between 1948 and 1952, whereas the GDR got nothing. On top of this, the FRG was relentlessly hostile to the very existence of the GDR. Under the Hallstein Doctrine from 1955, the FRG refused to maintain diplomatic relations with the government of any state (with the exception of the USSR) that enjoyed diplomatic relations with its eastern rival.

The GDR was never going to be able to compete economically with its western counterpart. Hoyer outlines how, by the 1980s, with declining Soviet aid, the GDR had fallen into a deep economic crisis — and had to turn to its western rival for financial assistance. These melancholy facts, it is claimed, showed the inferiority of the GDR’s post-capitalist economy in comparison with the FRG’s free market capitalism. Hoyer dismisses this, writing that while historians “have been quick to point to the planned economy as the root of failure ... the impact of the economic system is impossible to measure when the basics are missing — from natural resources, energy and industry to a stable currency.” It is therefore remarkable that despite these problems, the GDR was able to achieve a measure of prosperity and living standards far beyond those in the Soviet Union and the other Eastern Bloc states. Indeed, by 1950, the GDR had regained the industrial production levels of 1938; a tribute to the hard work and self-sacrifice of the country’s working class.

Yet Hoyer does not shrink from discussing the GDR’s dark side. The Socialist Unity Party (SED) soon fell into the same ideological straitjacket as Stalin’s Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The party was formed by the fusion of the Communist Party (KPD) and the eastern organisation of the Social Democratic Party at a conference in Berlin on April 21, 1946, despite misgivings among the rank and file of both organisations. According to Wolfgang Leonhard, “Little could I guess that evening that, of the participants at the assembly to unite the two parties, more than half would within a few years have been expelled from their posts, degraded, falsely accused, or eliminated by the purges.”[1] Despite the name of the new state, there was precious little democracy in it. Although Hoyer adopts the GDR’s claim that it was the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and the party claimed to represent the workers and peasants, the GDR was in fact a dictatorship over the proletariat. The KPD had suffered terribly under the Nazis, and many — probably most — of its members who fled to the Soviet Union had perished during the insanity of Stalin’s purges. It seems clear that most of the more independent-minded KPD members perished, leaving the field clear for arch-Stalinists like Ulbricht and the sinister Stasi chief, Erich Mielke who had avoided that fate and redoubled their loyalty to the dictator in the Kremlin.

Just how hollow was Ulbricht’s claim to represent the working-class came in 1953, when, fed up with constant shortages of consumer and essential goods, and with the ever-pervasive interference in their lives, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike and demanded the resignation of Ulbricht, and his associates in the state and the ruling Socialist Unity Party. The uprising was repressed with brutal force by the Soviet military, which led a dismayed Bertolt Brecht to write his satirical poem ‘The Solution’:

After the uprising of the 17th June

The Secretary of the Writers Union

Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee

Stating that the people

Had forfeited the confidence of the government

And could win it back only

By redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier

In that case for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?

Nevertheless, Ulbricht was spooked by the disturbances and back-peddled on some of the more oppressive aspects of rule. More resources were put into the production of consumer goods and housing construction was stepped up.

Meanwhile, the FRG’s comparative prosperity was a constant allure. By 1961, some 300,000 people — many of them skilled workers and professionals — were leaving the GDR for the West each year. The GDR was in danger of haemorrhaging to death. Ulbricht’s solution was to build the Berlin Wall — a hard border dividing the two states set up in the German nation — and to order border guards to shoot to kill. In other words, he decided to imprison the population. The Wall was to remain in place until 1989, and many East Germans were to die trying to escape to the West. The government had also created another state instrument in the image of the USSR: the Ministry of State Security, abbreviated to the Stasi. Under its paranoid boss, Erich Mielke, the Stasi became what was probably the most pervasive and intrusive organ of surveillance and repression created anywhere in the world. By 1989, the Stasi maintained between 500,000 and 2 million collaborators, who spied on family, friends, neighbours and workmates, as well as 100,000 regular employees, and it kept files on approximately 6 million East German citizens — more than one-third of the population.

Yet Hoyer is careful not to conflate the GDR with the Nazi dictatorship, as is often the case. She told one interviewer that “one of the key differences is that Nazi Germany was all-pervasive, it entered every aspect of your life, whereas in the GDR you could live a private life, so long as you didn’t put your head above the parapet… And then, of course, there wasn’t the genocide. As obvious as that sounds, it’s often forgotten in the way the two systems are compared.”

With rising living standards, heavily subsidised rents, free healthcare, steadily increasing access to higher education and training, and assured employment, many East German citizens were reasonably content or even happy with their lives. Even the much mocked Trabant cars with their two-stroke engines allowed people greater mobility. In two important areas, the GDR surpassed the West and even led the world. By the 1980s, over 90 per cent of East German women worked outside of the home and the GDR had achieved the highest levels of female employment in the world. In contrast, only half of West German women were in the paid workforce, most of them in part-time work. “It had become”, Hoyer tells us,

entirely normal for East German women to have a career and children with little compromise. Childcare from birth had become readily available and practically free. Running from 6 am to 6 pm, it was designed to cover regular working hours, allowing both parents to work full time. While the West German system had come a long way since the 1950s, childcare was still considered a personal choice requiring private funding and involvement from parents as well as often only being available for parts of the working day.

Access to higher education for the working class was another area in which the GDR could feel justifiably proud. Hoyer notes that “talented students and workers were encouraged and financially supported to continue to train, learn and study in the field that matched their talents.” Since reunification, however, “Germany has perpetuated the social rigidity of West Germany”, with a UNICEF study ranking Germany “in the bottom third for equality of chances of primary school children from different social backgrounds.”

Despite these very real achievements, Hoyer tells us that by the 1980s the GDR was losing its sense of direction. Dissident intellectuals had always gone West, willingly or otherwise, but now independent social movements were springing up, often under the auspices of the Protestant churches. East German society had become increasingly militarised, with the border with the FRG forming the front line in the Cold War and this alienated significant sections of the population. A fresh impetus for change came with the accession of Gorbachev to the leadership of the USSR, and many East Germans believed that his policies of Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring) should also apply to their own country. Gorbachev also said that the Eastern Bloc countries should be allowed to go their own way and determine their futures and forms of government without the fear of Soviet intervention as had been the case with Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

The system began to unravel. By 1989, hundreds of thousands of people had taken to the streets demanding fundamental reforms. This was anathema to the Stalinist hardliners, who responded with brutal force. But many other SED leaders lacked the appetite for this. On November 9, 1989, SED official Günther Schabowski announced that the GDR’s citizens were free to come and go across the border. In fact, with the earlier opening of the Hungarian border, some 200,000 East Germans had already visited the West. The GDR’s end was fast approaching. The following year, following a free election, the GDR was absorbed into a unified German state.

Any hopes that East German ways of doing things would be respected were soon dashed. Western officials moved in to begin the process of assimilating the East German economy, which meant selling off state-owned industry — a process marked by deep corruption — and closing down vast swathes of it deemed to be uneconomical: 4000 companies within the first twenty months, and only one-quarter of employees in state-run enterprises kept their jobs. Many proudly skilled workers found themselves in casual unskilled work: some, as Hoyer writes, in “the disheartening task of dismantling factories so they could be sold.” Some were even forced to “relearn jobs they had been doing for decades.” Complaints were dismissed as “moaning”, and “many West Germans argued that it was to be expected that the transition would be economically painful in the short term — a natural consequence of the inferiority of socialism.” In the process, many of the social gains won by East German workers — women in particular — were dismantled. “In the first two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, half of all the available places for children under three years old were scrapped … [and] the downhill trend continued to 2007 … [when] there were only places for 40 per cent of this age group.” In Hoyer’s melancholy words: “Many East German mothers suddenly found it difficult to square motherhood and career opportunities, and they were baffled when they had to justify why they even wanted both.”

Looking back to the swirl of events that led to the demise of the GDR, one wonders if it could have been different. Certainly, left-wing intellectuals such as Stefan Heym and Christa Wolf believed so. On November 28, 1989, they joined with twenty-nine other public figures to publish “An Appeal For Our Country”. It is worth quoting full as a reminder of “what might have been”:

Our land is in crisis. We cannot and will not continue to live the way we have done. The leadership of a party has usurped the control of a people and its institutions, all areas of our lives have been dominated by Stalinism. Without the use of violence, by means of mass demonstrations the people have started a process of revolutionary renewal which is developing at breath-taking speed. We do not have much time to find a way out of this crisis.

EITHER

we demand the continued independence of the GDR. In co-operation with those states and stakeholders prepared to help, we should muster all our strength to develop a society of solidarity, in which we guarantee peace and social justice, freedom of the individual, freedom of movement for all and the protection of the environment.

OR

we have to accept that the powerful economic forces — along with the unacceptable conditions that influential West German industrial and political figures demand in return for their support — will lead to a sell-out of our material and moral values, and, sooner or later, an assimilation of the GDR by West Germany.

Let us choose the first path. We still have the chance to build a socialist alternative to West Germany, in equitable neighbourliness with the states of Europe. We have not forgotten the anti-fascist and humanist ideals with which we began.

We call on all citizens who share our hopes and our fears to sign this appeal.

Berlin, 26th November 1989

One million East German citizens did sign the Appeal, but as Hoyer notes, “the public mood was drifting in a different direction.” The appeal came too late and became a footnote of history. Still, the appeal for democratic socialism should be more widely known. There are many reasons for the eventual collapse of the GDR, but one of the most important was the hidebound Stalinism that rejected democratic oversight and independent thought and constructed a monstrous apparatus of surveillance and control that in the end depoliticised the population. In one demonstration in the months before the GDR’s collapse, the police tore down a subversive banner inscribed with the following words:

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party — however numerous they may be — is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently.

Those were the words of Rosa Luxemburg, one of the founders of the German Communist movement, and a passionate partisan of democratic socialism who insisted that dictatorship of the proletariat means “dictatorship of the class, not of a party or of a clique … on the basis of the most active, unlimited participation of the mass of the people, of unlimited democracy.”

Notes

[1] Wolfgang Leonhard, trans. C.M. Woodhouse with an introduction by Günter Minnerup, Child of the Revolution (London: Ink Links, 1979), 357.