Commemorating November 29, 1943: The founding of a new Yugoslavia

A few days ago, the Serbian government announced its decision to demolish the iconic Yugoslavia Hotel, a landmark badly damaged during the 1999 NATO bombing campaign, to make way for a luxury Ritz-Carlton Hotel. Opened in 1969, the Yugoslavia Hotel was the largest in the entire federation and a remaining symbol of a country that no longer exists. Yet, even as the physical traces of Yugoslavia fade, its historical significance and virtual presence remain as potent as ever. This enduring legacy prompts us to reflect on the transformative vision and global impact of Yugoslavia, as we commemorate the anniversary of its founding on November 29.

On November 29, 1943, amid the turmoil of World War II, the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) proclaimed the foundation of the new Yugoslavia in Jajce, Bosnia. This moment marked the birth of a federation that envisioned a radically different future from the inequalities and divisions of the royalist past. Underpinned by the principles of “brotherhood and unity,” the Yugoslav project sought to transcend the ethnic, social and economic cleavages that had defined the interwar kingdom.

For decades, November 29 was celebrated as Republic Day across the federation. It was a day of parades, cultural events and communal reflection on the revolutionary legacy and aspirations of the socialist state. Families would gather, workers would reflect on their contributions, and students would learn about the struggles and achievements of a united Yugoslavia. The day symbolised not only the victory over fascism but also the promise of a society built on equality, solidarity, and collective progress. Even after the collapse of Yugoslavia, this day was celebrated in Serbia until 2001. I vividly remember attending a state reception hosted by Slobodan Milošević in 1998 at the Sava Center — an iconic venue in Belgrade that hosted the last congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. That moment, like the day itself, evoked both the grandeur and the contradictions of Yugoslavia’s legacy.

The transformational promise of the new Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia’s founding ideals resonated deeply with its working masses, who were mobilised to rebuild a war-torn country and embark on an ambitious journey of socio-economic transformation. The vision was clear: to eradicate the inequalities of royalist Yugoslavia and forge a society where all nations and nationalities could thrive.

The boldness of the Yugoslav project becomes even more remarkable when viewed against the backdrop of bitter inter-ethnic strife and the atrocities of World War II. The horrors of the war, such as the genocide of Serbs, Jews, Roma, and anti-fascist Croats in the Independent State of Croatia, along with the other brutalities and divisions sown by the war, left deep scars on the peoples of Yugoslavia. Overcoming these wounds required a revolutionary vision that went beyond simple reconciliation.

The founders of socialist Yugoslavia, firmly convinced that a new socially just state belonging to the working people of all nations could unite its citizens, embarked on a transformative project that sought to transcend the past. This vision was grounded in the principles of “brotherhood and unity,” not as mere slogans but as a deliberate strategy to foster solidarity among the country’s diverse ethnic groups. The idea was clear: only a state based on social justice, equality, and shared prosperity could heal the divisions and create a better future.

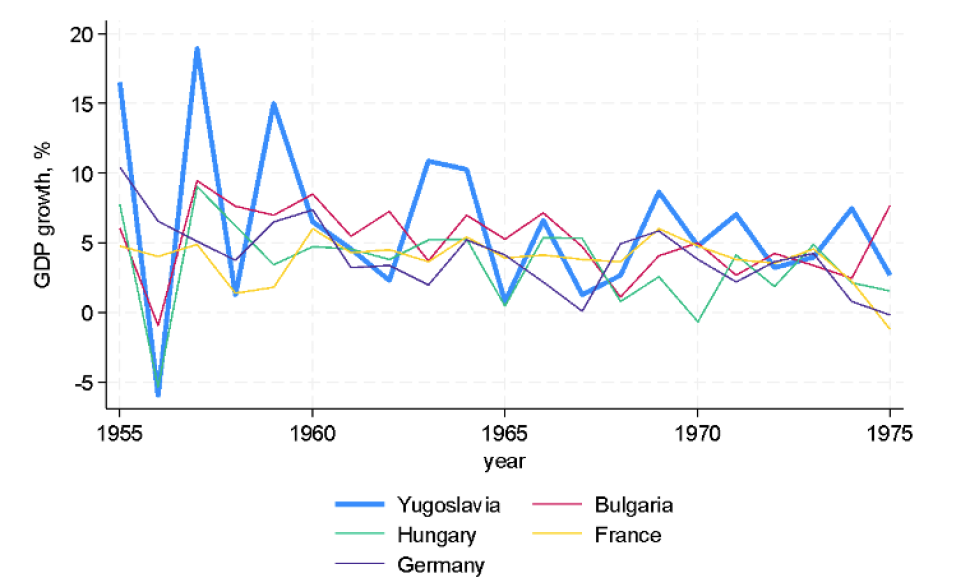

In the three decades following its founding, Yugoslavia achieved remarkable progress. During the 1950s to ’70s, a period often called “the glorious thirty” for the widespread economic growth across Europe, Yugoslavia stood out as one of the fastest-growing countries on the continent. This can be observed in Figure 1: while volatile, Yugoslavia’s growth rate was often above not only other socialist countries but also such European powerhouses as Germany and France. On average, the Yugoslav economy grew at 6.2% annually between 1955-75 compared to 5.2% in Bulgaria, 3.5% in Hungary, 3.8% in France and 4.0% in Germany. Yugoslavia’s GDP tripled over this period. From predominantly agrarian, the country transformed into a modern industrial state with advanced industries, such as production of automobiles, aircraft, and electronics. Through its unique model of socialist self-management, the country combined industrial modernisation with grassroots participation, creating opportunities for millions.

A grand experiment in socialism

Whereas all socialist countries experimented to some extent — though in the Soviet Union this experimentation ended rather early, and in countries such as Hungary and Czechoslovakia it was checked by Soviet interventions — Yugoslavia was arguably the most prone to experiment. Its entire post-war development was one grand experiment in a creative effort to align the country’s functioning with the tenets of Marxism. Disappointed in etatism after a short period, Yugoslavia embarked on the ambitious project of building self-management socialism, where economic and political decisions rested with working collectives rather than state bureaucracies, as in the Soviet Union.

This drive for experimentation was enshrined in the Program of the League of Communists, which declared nothing that had been created “can be so sacred that it could not be superseded by the better, the more advanced, the more humane.” Tito famously argued that workers’ self-management was the strongest bulwark against the nationalism that threatened the country: “There is no Serb or Croatian proletariat,” he declared. “There is but one Yugoslav proletariat.” At its height, Yugoslavia’s experiments in workers’ self-management drew the attention of both Western and developing nations, eager to study its novel approaches to governance and economic organisation.

Some critics argue that these experiments pushed Yugoslavia too far and sowed the seeds of its collapse, while others, such as Branko Horvat contend that the country ultimately fell apart because it never fully implemented workers’ self-management. As the concept of self-management regains attention in both heterodox and mainstream economic discussions, the Yugoslav experience remains profoundly relevant, calling for renewed analysis of its successes and failures.

A global leader in Non-Alignment

The transformational promise of Yugoslavia extended beyond its borders. By the 1960s and ’70s, the country emerged as a leader in the global Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), advocating for an alternative path in the polarised Cold War world. Yugoslavia’s role in the movement was not only unique but also groundbreaking. It was one of the very first socialist countries — and arguably the only one in its early stages — to join the NAM, long before the thaw in relations between the West and the Soviet bloc. This was a courageous and well-thought-out political action, signaling Yugoslavia’s commitment to an independent foreign policy that rejected alignment with either superpower.

Unlike other non-aligned countries, whose non-alignment was often born of anti-colonial revolutions or post-colonial defiance against former imperial masters, Yugoslavia’s non-alignment emerged directly from the dynamics of inter-bloc politics. It was the product of an authentic Communist revolution striving for independence and equality, not just within its own borders but also in the international arena. Yugoslavia’s non-alignment was the culmination of an arduous political journey that took it from the fringes of European bloc politics to the forefront of global diplomacy. From this unique position, Yugoslavia set the pace of political developments both within NAM and across the Third World during the Cold War era, shaping a new ideological and foreign policy response to the dominant currents in international relations.

Yugoslavia played a pivotal role in shaping NAM, providing a bridge between the Global North and Global South. This dual position allowed the country to act as what some scholars have termed a “liminal hegemony” — a space between the developed and developing worlds. On one hand, Yugoslavia provided leadership for the Global South, helping to unify the newly independent nations of Africa, Asia and Latin America under a shared agenda of anti-imperialism and equitable global development. On the other hand, its socialist model, unique economic experiments, and relatively developed economy gave the movement greater international credibility and positioned it as a legitimate third force in global politics.

Under Josip Broz Tito’s leadership, Yugoslavia was instrumental in convening the first NAM summit in Belgrade in 1961, which brought together representatives from 25 countries to articulate a vision of international cooperation, peace and solidarity. Unlike the Soviet Union’s focus on ideological conformity, Yugoslavia’s engagement with NAM was pragmatic, emphasising decolonisation, economic independence and peaceful coexistence. This approach resonated with many post-colonial states seeking to navigate the treacherous waters of Cold War politics without succumbing to the pressures of alignment.

Yugoslavia’s contributions to NAM extended beyond rhetoric. It offered technical and developmental assistance to Global South countries, supported their anti-colonial struggles, and advocated for a New International Economic Order that prioritised the needs of the developing world. By setting the pace of NAM’s political agenda, Yugoslavia shaped key debates on sovereignty, development and global justice during a crucial period in world history.

Through its “liminal” position, Yugoslavia enhanced its own international standing while reinforcing NAM’s role as a vital actor in global diplomacy. NAM’s principles of sovereignty, equality and non-interference — principles that Yugoslavia helped champion — continue to inspire debates about global governance, justice and the legacy of colonialism. In this way, Yugoslavia’s unique role in NAM remains a testament to the possibilities of an independent and principled foreign policy, rooted in the ideals of solidarity, equality, and peace.

Legacy and reflection

As we remember November 29, we celebrate not just the birth of a new Yugoslavia but the ideals that mobilised a generation to dream of a fairer and more equitable society. Yugoslavia was a goal-driven state, whose continuous experimentation reflected the ambition of its revolutionary vision. None of the successor states can boast of such a transformative goal. The pursuit of European Union membership by countries such as Serbia, Bosnia and North Macedonia pales in comparison — unless one seriously believes that the EU represents Communism.

In its role as a leader of NAM, Yugoslavia demonstrated a bold and innovative approach to international relations. It transcended the binaries of the Cold War, setting the pace for political developments in the Third World and offering a pragmatic yet principled vision of global solidarity. Yugoslavia’s “liminal hegemony” between the Global North and South was not just a political strategy but a reflection of its revolutionary ideals — an effort to reshape global dynamics through equality, cooperation and mutual respect.

Yugoslavia’s dissolution not only marked the end of a visionary dream but also deprived an entire group of people of their country. By 1981, more than 1.2 million individuals identified as Yugoslavs, transcending the narrow confines of ethnic identities. For these people, being Yugoslav was not simply an administrative label but a lived reality and a unifying identity. With the collapse of the federation, these individuals were forced to adopt restrictive ethnic affiliations, often at odds with their personal sense of belonging. In a world where identifying as European has become fashionable, identifying as Yugoslav has become unpopular, even despised — a painful reminder of the ideological and cultural disintegration that accompanied Yugoslavia’s fall.

Domestically, Yugoslavia’s political and institutional design offered a unique experiment in federalism. With its high degree of federalisation, where decision-making was based on consensus between republics and autonomous provinces, and where republics held the right to enter into bilateral relations with other states and even had their own banks to exercise significant control over regional investment policies, socialist Yugoslavia can justly be considered a precursor to today’s EU. Its structure sought to balance national aspirations with the need for unity, offering a framework of shared sovereignty that echoes the EU’s founding principles.

However, the tragic splitting of Yugoslavia along ethnic lines and its eventual demise raise important questions about the EU’s future. Can the EU, faced with its own tensions — ranging from rising nationalism to economic inequalities — avoid a similar fate? What lessons can be drawn from Yugoslavia’s efforts to hold diverse communities together under a shared vision, and its failure to sustain this unity in the face of growing internal divisions? Yugoslavia’s experience serves as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale, underscoring the need for solidarity, adaptability, and shared commitment to common ideals to prevent fragmentation.

Against the backdrop of a continuous and deepening crisis of neoliberal capitalism, now coupled with the “long retreat” of the left from nearly all positions of power and influence, and amid an increasingly volatile international security environment, Yugoslavia offers valuable lessons. It stands as an example of principled yet measured politics, promoting de-escalation and international cooperation.

Today, the legacy of Yugoslavia calls for renewed reflection on its bold experiments in workers’ self-management, its independent and forward-looking foreign policy, and its steadfast commitment to unity and solidarity. It remains a powerful reminder that even in a divided and unequal world, an alternative vision of global and domestic politics — rooted in equality, justice, and collective progress — is not only possible but essential.