The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

First published at TNI.

Emirates Airlines’ first flight took off on 25 October 1985, flying from Dubai to the Pakistani city of Karachi, using an aircraft leased from Pakistan International Airlines. Today, Emirates has a fleet of more than 260 aircraft, serving over 136 destinations worldwide. In 2023, Dubai International Airport was ranked as the world’s busiest hub for international passengers for the tenth consecutive year.

Jebel Ali Port, located off the coast of Dubai, was inaugurated in 1979, followed by the establishment of the Jebel Ali Free Zone six years later. In 2023, it was the world’s tenth-busiest container port.

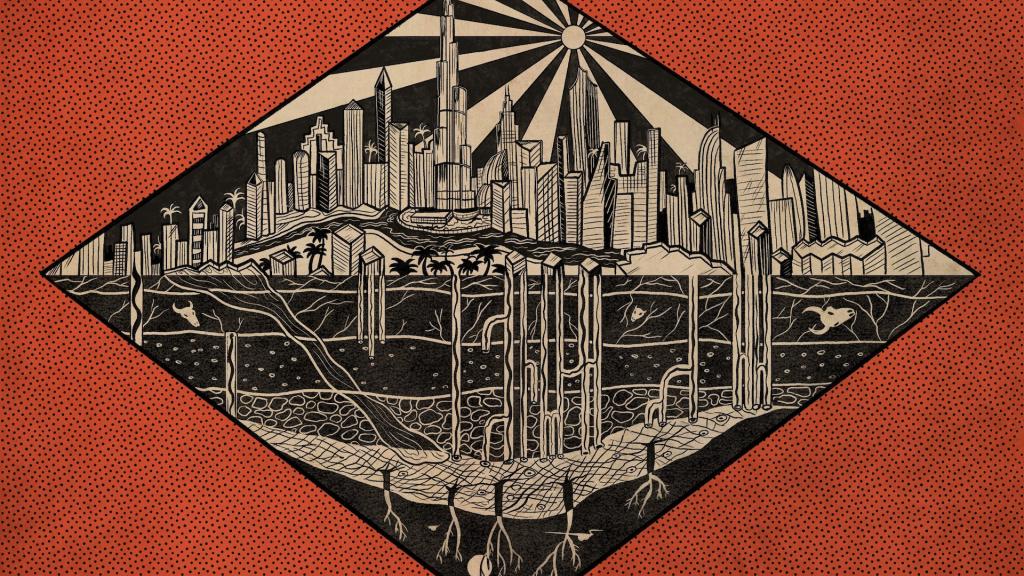

Despite being situated on the southern coast of the relatively small and shallow inland sea known as the Arabian Gulf — or Persian Gulf, depending on geographical, historical, or cultural perspectives — Dubai has realised its vision of becoming a central hub in what they describe as a ‘ trade network reaching one-third of humanity’.

Since the turn of the century, Dubai has achieved even more. The city’s brand has become synonymous with luxury, high-end living, and economic growth. It has become a global hub for business, tourism and entertainment, serving as a development model admired and aspired to by politicians, businesspeople and citizens across the Middle East and Africa (MEA) region.

However, it is Abu Dhabi, the more affluent and influential yet less recognised sister emirate of Dubai, that has been the driving force behind the emergence of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in recent years as a major power in the politics of the region.

The UAE has invested billions of dollars in several African countries across sectors such as mining, oil, infrastructure, logistics and agriculture, gaining control of significant portions of their national economies.

It has also played decisive roles in countries affected by the uprisings and protests collectively referred to as the ‘Arab Spring’, particularly Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen. Its support for the Ethiopian government has significantly influenced the outcomes of the Tigray War and developments in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea region. Moreover, the UAE is deeply involved in the ongoing war in Sudan, backing the notorious Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia, which has been accused of committing war crimes, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Moreover, the UAE has worked closely with militias and employed mercenaries in various conflicts, effectively influencing who governs these countries and how they are governed, thereby positioning itself as the region’s new kingmaker.

The UAE has expanded its economic footprint across Africa through investments in ports, airports and infrastructure projects. These ventures are not solely driven by business interests but also serve as strategic moves to extend its influence. The UAE has substantial investments in agricultural land, renewable energy, mining and telecommunications, as well as extensive military cooperation agreements, making it a significant player in regional geopolitics.

Using the framework of sub-imperialism1, a concept that was introduced by the Brazilian Marxist scholar and activist Ruy Mauro Marini, provides valuable insights for analysing the UAE’s strategies and impacts. It demonstrates how the UAE can simultaneously be both a subject of imperialism and an agent of imperialist practices within its spheres of influence while challenging traditional imperialist actors.

Sub-imperialism, in this context, refers to a phenomenon where a country, while not being a major global imperial power, acts in ways that align with or support the interests of imperial powers and behaves in an imperialist manner within its own region. It is characterised by actions that extend a nation’s political, economic and military influence over other nations or regions, often on behalf of, or in collaboration with, dominant global powers.

The UAE, as a peripheral nation that engages in imperialist practices within its own region while remaining dependent on the United States (US), a core imperialist power, exemplifies the transformation into a sub-imperialist state. Other sub-imperial examples from the Middle East include Israel, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Throughout the 2010s, in many ways the sub-imperial ambitions of the UAE and Qatar mirrored the Israeli model. Despite being small in both size and population and situated in a hostile regional environment, they leveraged their wealth and strategic relationships with Western powers to exert influence across the region. Both nations have supported various factions, including mercenaries and insurgents, to advance their national interests and assert regional dominance.

Saudi Arabia, by contrast, significantly larger in size and population, has exhibited features of sub-imperialism since the mid-twentieth century through direct military interventions and political, financial and religious activities that influence the region, while relying on the US for defence and aligning closely with its economy.

The UAE’s regional strategy is widely recognised as being driven by ambitions of economic hegemony, political expansion and countering perceived threats from Islamic political movements and from Iran. An overlooked factor, however, is the regime’s survival instinct and its fear of popular, democratic or revolutionary movements. This aspect is often neglected owing to limited awareness of political activism and movements within the UAE and the broader Gulf region.

Studying the UAE’s sub-imperialist role in Africa is therefore critical to understanding its substantial influence in reshaping regional geopolitics and global capitalism. This analysis helps to shed light on pathways for resistance and justice movements to challenge these power structures effectively.

Humble beginnings

The UAE has come a long way since its formation in December 1971. Initially composed of six emirates, with the seventh joining in 1972, the federation was established following the end of British protection treaties. At its inception, the UAE was a small, vulnerable nation with a population of just 340,000 and minimal signs of modern statehood. Surrounded by powerful neighbours like Iran, which occupied three of its islands on the eve of its formation, and Saudi Arabia, which withheld recognition until a border dispute was settled, the UAE faced significant regional challenges.

Over the next 30 years, under the leadership of its first president, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan, the UAE adopted a low-profile diplomatic approach while embarking on rapid modernisation fuelled by its vast oil and gas reserves. Despite its considerable wealth and high per capita gross domestic product (GDP), the UAE remains an autocratic state with a highly stratified society. The current population of about 11 million includes only one million Emirati nationals, with the rest comprising a diverse mix of resident foreigners and migrants from over 200 nationalities, primarily from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Most of these non-citizens lack the right to permanent residency or a path to naturalisation.

The wealth and power within the UAE are concentrated in the ruling families of Abu Dhabi (Al-Nahyan) and Dubai (Al-Maktoum), along with a few closely connected business elites. Abu Dhabi, the country’s capital and the wealthiest emirate, holds most of the political and economic power, while Dubai is known for its economic dynamism and global appeal. The other five emirates have limited resources and influence.2

The Emiratis’ social fabric is also marked by religious and ethnic divisions.3 Although Sunni Muslims dominate, there is a significant minority of Shiite Muslims who often feel marginalised and are viewed with suspicion due to their perceived ties to Iran. Within the Sunni community, Abu Dhabi and Dubai ruling families belong to the Maliki school of thought, while most of the Sunni population follows the Hanbali school. Ethnic distinctions further complicate the social hierarchy, with Bedouin Arab tribes traditionally holding the highest status, followed by coastal Arabs, families of recent Yemeni descent and non-Arab groups (Ajam). At the lowest position are the descendants of enslaved Africans.

The expatriate community is also divided into three main classes: a small, wealthy upper class of business elites; a broad middle class of professionals, employees and businesspeople; and a large lower class of labourers and unskilled workers, predominantly from Southeast Asia and increasingly from Africa.

Before independence, the UAE, like other Gulf states, relied heavily on British support for security against regional threats, eventually transitioning to US dominance. During the 1970s and 1980s, the UAE navigated several significant geopolitical events, including the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Iranian Revolution, the Soviet-Afghan War and the two Gulf Wars, while maintaining a low profile and aligning with Western interests. These events coincided with the emergence of small but notable socialist, Arab nationalist, communist, and Islamist movements, including the Muslim Brotherhood, in the UAE and the broader Gulf region. Although these movements never gained substantial influence owing to the government’s effective suppression and control over political life, the regime has always considered them a threat.

Overall, the UAE’s transformation from a small, vulnerable state to a sub-imperialist power has been marked by strategic use of its wealth and alliances to shape the political landscape of the Middle East and Africa. Its influence is felt through economic investments, military involvement and diplomatic outreach, making it a formidable actor in regional and global affairs.

The UAE’s strategic investments in Africa: Ports, logistics and sub-imperialist ambitions

Over the past decades, the UAE has invested close to $60 billion in African countries, making it the fourth-largest foreign direct investor on the continent, after China, the European Union (EU) and the United States. In the last two years alone, the UAE has pledged $97 billion in new investments in Africa, which is three times more than China’s commitments.

At the core of the UAE’s geopolitical strategy is its focus on acquiring port concessions that encircle the African continent, positioning the UAE to dominate global trade routes around Africa. Along with these port developments, the UAE is building logistical hubs and supply chain infrastructures deep within Africa. The two major players in this strategy are AD Ports Group, whose majority shareholder is the Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company (ADQ), a sovereign wealth fund (SWF), and DP World, which is fully owned by the Dubai government through its parent company, Port and Free Zone World FZE.

These companies are currently operating or have signed agreements to build and manage ports across Africa. In Northern Africa on the Mediterranean (Algeria and Egypt); in Western and Southern Africa on the Atlantic Ocean (Angola, Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Guinea and Senegal); on the Indian Ocean in Eastern Africa (Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania); and in the Red Sea region, including the Horn of Africa, with projects in Egypt, Puntland and Somaliland. They also have a port in Djibouti, which is subject to a legal dispute with the Djibouti government, and previously had one in Eritrea that was used as a military base. A port deal was also signed in Sudan but was recently scrapped by the de facto government in the light of the ongoing conflict.

In addition to coastal ports, the UAE has invested in dry ports and container hubs in the African interior, with significant hubs located in Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Tanzania.

These ports, alongside more than 70 logistical hubs across the African continent, play various roles in the UAE’s broader sub-imperialist strategy. They are positioned to not only facilitate land acquisition and resource extraction across Africa but also to serve the UAE’s military ambitions.

Landgrab: UAE’s African land acquisitions

The UAE has emerged as a significant global land investor, with countries across Africa being a key focus. In recent years, the country has increasingly acquired land in several African nations for food production and carbon-offset projects.

The UAE’s ambitions go beyond producing food for its own population; it seeks to position itself as a global food trade hub. In 2022 its regional and international aggregate food trade amounted to more than $27 billion. Currently, the UAE imports about 90% of its food, and after crises like the 2007-2008 global food price spike, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it has aggressively pursued agricultural lands to secure its food supply. These investments are part of a coordinated strategy led by the Emirati government, where the line between public and private interests is blurred. Major Emirati companies, often linked to the ruling families — particularly the Al-Nahyan family of Abu Dhabi and the Al-Maktoum family of Dubai — play key roles.

The main investors are companies owned by sovereign wealth funds, such as ADQ, Mubadala, and International Holding Company (IHC). IHC, chaired by Sheikh Tahnoon Bin Zayed, a brother of the UAE’s President, is Abu Dhabi’s largest listed company. Sheikh Tahnoon also chairs ADQ and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), and owns Royal Group, a prominent private investment firm.

The UAE has acquired agricultural land in Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Morocco, Namibia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Uganda and Tanzania. These investments, often extractive in nature, have significant impacts on local populations and ecosystems. In many cases, water-intensive crops such as alfalfa are grown to feed livestock in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, illustrating that these activities constitute not only landgrabs but also water grabs. The large-scale production of crops, fruits, vegetables and livestock often results in the depletion of local resources, leading to food insecurity and environmental degradation for the host countries. Moreover, raw materials imported to the UAE are sometimes processed and sold back to African countries at significantly higher prices.

In some instances, the UAE’s influence in securing food supplies has had broader social and environmental consequences. Notably, the UAE and other Gulf nations have influenced conflicts between farmers and herders in Sudan and Somalia, facilitating the mass export of livestock at the expense of local communities and ecosystems.

The UAE has also acquired vast tracts of land in Africa for use in the emerging carbon economy. After purchasing carbon credits, ostensibly generated from preserving forests, the UAE sells these credits to companies seeking to offset their emissions. Media reports suggested that one Emirati company, owned by a member of Dubai’s ruling family, has purchased significant portions of land in Liberia, Zambia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Carbon-offset programmes, such as those pursued by the UAE, have been criticised for being ineffective in reducing carbon emissions, but are often seen as enabling continued pollution by countries and large corporations, a practice often referred to as ‘greenwashing’ or ‘ carbon laundering’.

The UAE has positioned itself as a key player in the carbon economy by establishing carbon exchanges and financing related projects. It has leveraged platforms like the UN Climate Change conferences, particularly COP28 in Dubai in 2023, to advance policies that promote the extension of fossil fuel production while marketing its involvement in carbon offsets. The UAE is involved in all stages of the carbon-offset industry, from generating to purchasing carbon credits, becoming a central player in the global wealth extraction system that exploits African resources while engaging in greenwashing.

While the UAE and its companies often highlight the employment and training opportunities created by their investments (unlike China), in reality the UAE relies heavily on local and foreign workers, as it lacks enough qualified citizens who can work in these regions. In many instances, such as in Liberia and Kenya, the UAE’s land acquisitions in Africa have been linked to human rights violations, including the forced eviction of local populations and allegations of corruption involving local officials.

Mining and gold exploitation

In recent years, the UAE has become increasingly active in securing mining deals across various African countries, particularly in Angola, DRC, Zambia and Zimbabwe. These investments have focused on critical minerals such as cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium and nickel.

The UAE’s involvement in the gold trade has raised significant concerns. Dubai, in particular, serves as the world’s second-largest gold importer and the main destination for gold mined in African countries. Notably, Dubai imports more gold from countries that produce relatively small amounts of the metal, such as Rwanda and Uganda, and reports higher gold import values than are declared as exports(external link) by these countries. This discrepancy has led to allegations that Dubai has become a hub for gold smuggling and money laundering through its gold markets and refineries.

In 2022, the US Treasury Department stated that ‘ more than 90 percent of DRC gold is smuggled to regional states, including Uganda and Rwanda, where it is then often refined and exported to international markets, particularly the UAE’. This suggests that the UAE plays a significant role in the global trade of illicit gold.

Sudan is another prominent example. Much of Sudan’s gold is smuggled to the UAE, even during the ongoing war in the country. Both the RSF and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have facilitated the production and smuggling of this gold to the UAE, a practice that dates back to when these groups were allied against civilian forces during the transitional period between 2019 and 2021.

These examples illustrate how the UAE’s investments in African ports and logistics align with its broader strategy to exploit natural resources on the continent, enabling the extraction of significant economic value from African nations.

The September meeting between President Biden and the Emirati President, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ) summed this up, recognising UAE’s ‘leadership in strategic investments globally to ensure reliable access to critical infrastructure including, ports, mines, and logistics hubs through the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, the Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company, Abu Dhabi Ports, and DP World’.

Militarised investments

The UAE has signed a growing number of military cooperation agreements with countries where it has invested in strategic sectors such as ports, logistics hubs, agricultural lands, renewable energy, telecommunications and mining. These agreements often begin with military training and education initiatives and may later expand to include the export of UAE-manufactured arms. In some cases, the UAE has deployed soldiers and provided military equipment for active combat operations, such as those against militant Islamist groups in the Sahel region and Somalia, as well as its participation in the NATO intervention in Libya. The UAE has also supplied drones to the Ethiopian government, playing a critical role in shifting the balance of power in Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s favour during the conflict with Tigrayan forces.

The UAE has also established military bases in countries such as Chad, Eritrea, Libya and Somalia (including the Puntland and Somaliland regions), which have been used by UAE forces and affiliated militias in ongoing conflicts, particularly in Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. In Libya, the UAE has been a key supporter of Haftar’s militia since the onset of the second civil war in 2014, providing political, financial, military and logistical aid. It has violated arms embargoes by supplying Chinese and Russian weapons to the militia and recruiting mercenaries to bolster its forces.

A sub-imperialist in the making

The UAE did not exist when Ruy Mauro Marini introduced the concept of sub-imperialism in the 1960s, focusing on Brazil and Latin America more broadly. In subsequent decades, Marini and other scholars touched on countries such as Egypt, Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Over the last 20 years, the region’s geopolitics have shifted significantly, so it is worth analysing the evolving roles of countries like the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia through the lens of the sub-imperialism framework.

In this framework, the UAE exhibits the hallmarks of a sub-imperialist state: a peripheral nation dependent on the US, a core imperialist power, while engaging in imperialist practices within its region. Marini’s theory identifies how such nations concentrate and centralise domestic capital, fostering national monopolies that mirror advanced capitalist economies. These monopolies, like the UAE’s Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) in energy, DP World in global trade and the wealthy SWFs, are emblematic of the UAE’s transition to a sub-imperialist role. Furthermore, these nations actively suppress revolutionary movements, transfer value and surplus value from weaker economies (like those across the African continent), and exploit labour (locally and in dependent regions) — all traits that align with the UAE’s conduct.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia viewed the mass uprisings of the ‘Arab Spring’, which began in late 2010, as a significant threat to their conservative monarchical regimes, particularly as they coincided with the Obama administration’s pursuit of a nuclear agreement with Iran — a development the UAE perceived as an existential threat. Throughout most of the 2010s, the UAE and Saudi Arabia remained close counterrevolutionary allies in confronting the ‘Arab Spring’ popular movements. The UAE’s response to these uprisings largely shaped its long-term geopolitical strategy, which includes economic, political, diplomatic, technological, public relations (PR) and cultural dimensions.

In addition to the UAE’s role in Libya, along with Saudi Arabia it intervened militarily in Bahrain to suppress protests and provided financial aid to Oman to quell unrest. Domestically, the UAE responded to dissent with a strong crackdown, imprisoning 132 Emiratis, many of whom were Islamists, who had petitioned for reforms to the Federal National Council’s electoral process. Both countries launched a devastating war in Yemen, resulting in one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes of the modern era. In Egypt and Tunisia, the UAE supported efforts to undermine democratically elected governments, contributing to coups that reversed democratic transformations.

Qatar, with its own sub-imperialist ambitions, positioned itself on the opposite side of the UAE and Saudi Arabia — not out of support for popular movements or a commitment to democratic progress, but because it backed the Muslim Brotherhood and other political Islamist movements, which in many countries were poised to gain the most from the Arab Spring.

Sub-imperialism in Sudan: A growing role

The UAE’s involvement in Sudan over the past decade reflects its growing sub-imperialist tendencies, particularly in regional dominance, economic exploitation and military intervention. Along with Saudi Arabia, it enlisted Sudanese soldiers from SAF and RSF to fight in the war in Yemen, providing financial support to Al-Bashir until his ousting in April 2019 following the mass protests that began in December 2018 (December Revolution).

Following Al-Bashir’s fall, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, along with Egypt, promoted a liberal peace-building process between Sudan’s civilian forces and military leaders resulting in the formation of a transitional government, which fell short of the aspirations of the Sudanese people. The three countries subsequently undermined the civilian side of the government, bolstering the military leaders with financial aid, military supplies and lobbying to entrench their power. The UAE also pushed Sudan towards normalising relations with Israel through the Abraham Accords, aligning Sudan with UAE-led regional strategies.

In October 2021, the three countries supported a military coup which further consolidated military dominance in Sudan. As tensions grew, the UAE’s backing shifted more decisively towards the RSF, contributing to the outbreak of war on 15 April 2023, which has since escalated into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

The UAE has been a hub for RSF financing, logistics, media, PR and political activities. Its covert support included allies like Russia’s (former) Wagner Group of mercenaries, Libya’s Haftar militia, and Chad. It also recruited mercenaries from as far as Colombia to fight alongside the RSF in Sudan. Despite these actions, the UAE publicly denies involvement and claims to be working for peace in Sudan. Countries such as the US and the United Kingdom (UK) have been unwilling to confront the UAE over its role, with reports suggesting they are cautious of provoking its discontent. In April 2024, the UAE cancelled ministerial meetings with the UK reportedly in response to frustration over its reluctance to defend the UAE at a UN Security Council meeting on Sudan. US officials were also reportedly displeased when envoy Tom Perriello supported the US rapper Macklemore cancelling a performance in Dubai to protest against the UAE’s support for the RSF.

However, as the UAE’s support for the RSF became widely known, Sudanese citizens began to question the true motivations behind its actions. While economic interests are a factor, the UAE could probably have secured these through collaboration with its Sudanese allies. It could not simply be because of its opposition to Islamists because the RSF leadership is filled with Islamists from Al-Bashir’s regime, with which it previously collaborated. Its support appears rooted in a broader agenda to oppose popular, revolutionary and democratic movements across the region, shielding its own ruling regime.

The UAE projects an image of a modern, progressive nation, although its actions in Sudan reveal ambitions that align with imperialist practices, inflicting immense suffering on millions of Sudanese citizens without facing significant international reprisals, much as the former imperial powers behaved.

Alignment with imperial powers and regional independence

The UAE’s alignment with the US underscores its dependency and intermediary status. Since the late 1960s, it has increasingly relied on the US for defence. It hosts US troops in military bases and advances US regional interests. It has participated in key events, such as supporting the Afghan Mujahideen against the former Soviets, backing Iraq in its war with Iran, opposing Iraq following Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, and assisting the US in the Balkan wars, among many other examples. In 2024, the US designated the UAE a Major Defense Partner, a title shared only with India, signalling the depth of their alignment.

At the same time, the UAE exhibits the autonomy typical of sub-imperialist states, leveraging inter-imperialist contradictions to diversify its alliances. For example, while historically investing heavily in the West, the UAE has expanded investments in China, Russia and South Korea. In 2023, a British official, commenting on Saudi Arabia, reflected these dependency dynamics saying ‘ We need them more than they need us’. Although the comment referred to Saudi Arabia, the sentiment captures the shifting dynamics of power in the Gulf, including the UAE’s growing leverage. This is further evidenced by the UAE’s role as the largest export market for US goods in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region for 15 years, and its total investments in the US, which amount to $1 trillion.

Politically and strategically, the UAE aligns with the US in its animosity towards Iran and its normalisation of relations with Israel, creating a mutual dependence between the two countries. As one of the key signatories of the Abraham Accords in 2020, the UAE plays a critical role in the US efforts to normalise relations between Israel and Arab nations, especially in the face of widespread popular opposition to US involvement in Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza.

Exploiting vulnerabilities in global power structures

The UAE’s ability to exploit Western institutional vulnerabilities reflects a broader decline in US strategic focus, particularly in Africa. The US State Department’s Africa office and diplomatic missions have historically struggled to attract top diplomats, creating opportunities for states like the UAE, China and Russia to expand their influence.

Simultaneously, the UAE’s relations with China and Russia have deepened. Bilateral trade with China has reached $95 billion, dwarfing its $31 billion trade with the US. A Chinese company has also built and now operates a second terminal at Abu Dhabi’s main port, Khalifa Port, under a 35-year concession. The UAE also joined the BRICS bloc in 2024, an indication of its growing independence. In 2023, it sold liquified natural gas to China in yuan for the first time, challenging the dominance of the US dollar in global trade. The UAE has also become a haven for Russian oligarchs and businesses seeking refuge from Western sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Militarily, the UAE has diversified its partnerships, signing an $18 billion deal with France for Rafale jets in 2021, acquiring Chinese drones, and collaborating with South Korea on nuclear energy projects, pledging $30 billion in investments there. China has also built a naval base near Abu Dhabi, highlighting the UAE’s complex position as both a US ally and an independent actor.

Lobbying power play

The UAE recognised that it could wield significant influence over the policies of superpowers through borderline legal practices such as lobbying and donating to think tanks and academic institutions. Over the years, the UAE has spent millions of dollars on lobbying, public relations (PR), consultancy and legal firms in the US and the UK to shape foreign policy, enhance its global image, and advance its economic, political and security interests.

These efforts have focused on influencing US and UK positions on regional conflicts, such as supporting the UAE’s stance in the Yemen war and countering Iran’s influence. Furthermore, the UAE aims to counter negative reports about its domestic authoritarian practices, corruption and controversial regional stances, including its support for militias like Haftar’s forces in Libya and the RSF in Sudan.

A significant part of the UAE’s lobbying efforts is dedicated to portraying itself as a beacon of stability, development and modernity in the region. It also works to secure its global economic and trade interests. However, many of these activities straddle the line of legality, often bypassing transparency requirements for lobbying and foreign agency rules. Large sums of money have found their way into the pockets of US and British lawmakers and officials.

The UAE has also contributed to the election campaigns of US politicians, including some presidential campaigns, and has capitalised on the ‘revolving-door’ practice. This involves hiring key personnel from various levels of the US and UK governments, administrations and security sectors as consultants or advisors to the UAE government or Emirati companies. Some were hired after retirement, while others were appointed to key government roles after spending time on the UAE payroll — examples include former British prime ministers Tony Blair and David Cameron, and former CIA Directors David Petraeus and Leon Panetta.

The UAE cultivated strong business relationships with Donald Trump and his children, both before and after his first presidency. Similarly, it made large payments to figures like Bill and Hillary Clinton for public speaking engagements after their terms in office.

Another significant avenue of influence involves the UAE’s generous funding of think tanks, universities and non-government organisations (NGOs) that shape strategic policies in the Middle East and Africa. Institutions like Chatham House in the UK, and the Middle East Institute and Harvard University in the US, are key examples of this strategy.

Activist strategies for UAE accountability

The UAE is primarily a trading nation, with its brand, reputation and image being of utmost importance. In a competitive world where many countries aspire to become hubs for commerce, tourism, finance and technology, the UAE is highly sensitive to anything that could tarnish its image. Negative media coverage is a particular concern.

Numerous examples from the ongoing war in Sudan demonstrate how media scrutiny influences the UAE’s actions and responses. On 4 July 2024, just four days after a flight tracker highlighted an increase in Emirati flights to Amdjarass in Chad, the UAE announced the opening of a hospital there. Similarly, four days after a damning New York Times report on 29 September 2024 revealed the UAE’s covert operation supplying weapons and drones and treating RSF fighters, the UAE’s official news agency reported a visit from the Chadian president, who praised the UAE’s humanitarian efforts. The following day, the Emirati Defense Ministry announced joint military exercises with Chad.

To challenge the UAE’s destructive, sub-imperialist role in the region, international activists and movements have several strategies at their disposal. Exposing the UAE’s actions through both mainstream and social media is crucial. Activists need to build a global, sustained campaign that links the UAE to its atrocities whenever the country is mentioned, including its violations to the rights of its people and the migrant community.

Celebrities can play an influential role by using their platforms to raise awareness about the UAE’s activities. Performers, artists and comedians can refuse to participate in events held in the UAE or sponsored by UAE companies and should publicly announce their refusal to do so, as the US rapper Macklemore did.

Shedding light on the UAE’s ‘sports washing’ practices is equally important. Big-name organisations like the Manchester City football club, owned by Emirati interests, should be called out for unethical practices. Boycotting UAE-hosted sporting events, such as the Dubai and Abu Dhabi Tennis Championships and the Dubai World Cup horse race, is essential, as is pressuring organisers of events sponsored by Emirati companies, such as the Wimbledon Tennis Championship, to cut ties. Activists should also target international sports events held in the UAE, such as the Abu Dhabi Formula 1, and push for their relocation.

To counter the UAE’s lobbying efforts and its influence on policymakers in countries like the US and the UK, activists need to expose these connections and highlight their impact on public officials’ decisions — especially when these decisions go against their own countries’ interests. There need to be efforts also to incorporate the fight against the UAE into broader campaigns against revolving-door practices, political lobbying and foreign influence in domestic politics. Activists should continue to build momentum towards greater transparency in politics, elections and official appointments, pushing for stricter rules on officials’ business activities while in office. They should at the same time pressure Western governments to halt arms sales to the UAE, which fuel conflicts like those in Sudan and Yemen, causing immense civilian suffering. Public campaigns could emphasise how these sales violate international law and democratic values, making it politically costly for governments to continue them. Activists in the US could oppose and pressure to strip the UAE from its recent designation as a Major Defense Partner of the US.

There is a need to oppose normalisation deals between Arab countries and Israel, such as the Abraham Accords, which side-line Palestinian rights and bolster authoritarian regimes. Highlighting the UAE’s hypocrisy in supporting conflicts while presenting itself as a peace-broker could help rally global support against such agreements.

Activists, researchers and journalists could collaborate with independent think tanks and research centres to secure funding for dedicated investigations into abuses of power and influence peddling by the UAE, with a particular focus on documenting the impacts on communities and populations. Similarly, they might also examine the actions of other sub-imperialist powers in the region, such as Israel, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, and explore their interactions with the UAE and with each other. It is essential, however, to avoid assuming that these actors are identical in their behaviour and strategies.

Such campaigns could help activists to hold the UAE accountable and challenge its sub-imperialist actions on the international stage.

Conclusion

The UAE’s transformation into a sub-imperialist power demonstrates how a peripheral state can leverage its wealth, strategic geography and alliances to exert outsized influence on regional and global affairs. Its investments in the infrastructure, agriculture and natural resources of many African nations, combined with military interventions and covert operations, have cemented its role as both a beneficiary and an agent of imperialist practices. At the same time, the UAE’s alignment with dominant powers like the US and its diversification of alliances with China, Russia, and others highlight the intermediary status and strategic autonomy that tend to characterise sub-imperialist states.

Typically, the UAE’s actions come at a significant cost to local populations, environmental sustainability and democratic movements. Its investments and interventions often lead to resource exploitation, human rights violations and destabilisation of the host countries. As the UAE continues to project an image of modernity and progress, it is crucial for activists, researchers and policymakers to expose its sub-imperialist practices and hold it accountable. By understanding the UAE’s role within the sub-imperialism framework, the global community can better challenge its actions and advocate for justice and equity in the regions it influences.

Husam Mahjoub is a co-founder of Sudan Bukra, an independent non-profit TV channel watched by millions of Sudanese viewers. A telecom professional and activist, he holds master’s degrees from the London Business School and Georgia Tech and currently lives in Austin, Texas. He has published articles on politics, human rights, the economy and international and cultural affairs.