Germany's genocide in Namibia

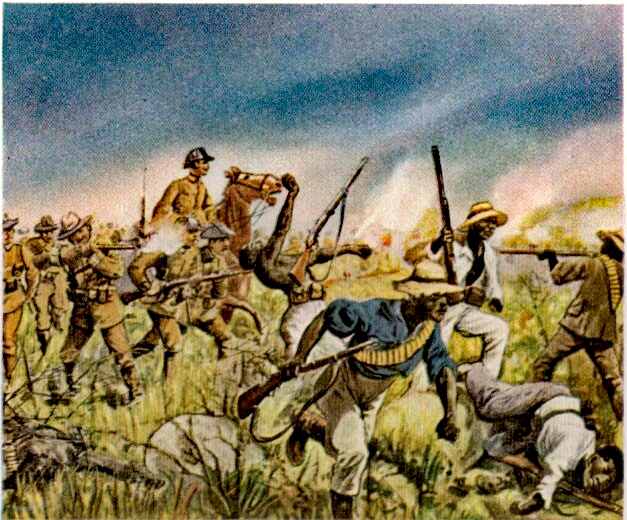

German troops kill the Herero, circa 1904. Painting by Richard Knötel (1857-1914).

Africa's Pambazuka News has devoted an entire issue to Germany's 1904-08 genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples (in Namibia). Below Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal posts the editorial and an article that details this shameful imperialist slaughter and modern Germany's refusal to adequately acknowledge and compensate Namibia for its crimes. Read the full issue HERE. Become a Friend of Pambazuka.]

* * *

By Eric Van Grasdorff, Nicolai Röschert and Firoze Manji

March 20, 2012 – Pambazuka News – On March 22, 2012, Germany's parliament will debate a motion to acknowledge its brutal 1904-08 genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples. Germany’s refusal thus far, and its less than even ‘diplomatic’ treatment in 2011 of the Namibian delegation at the first-ever return of the mortal remains of genocide victims, demands a reassessment of suppressed colonial histories and racism.

This special issue is a cooperation between Pambazuka News and AfricAvenir International.

The silence on Germany’s colonial past has become unbearable – both in Germany and in the affected countries. The current government of the Federal Republic of Germany seems not to be ashamed to emphasise that Germany supposedly carries a ‘relatively light colonial baggage’ because it lost its colonies after World War I. However short the country’s colonialist period might have been, it played a central role in the colonisation of the African continent. It was in Berlin that – on the invitation of the Kaiser and his Chancellor Bismarck – Africa was distributed among European countries in 1884–85. Well-functioning communities were brutally crushed in the clear aim to better control, dispossess and exploit the African peoples and their raw materials for the economic development of the imperial powers.

Germany, which has done commendable remembrance work about the Holocaust, seems to have forgotten or deliberately buried its violent colonial past. A past that hides the first genocide of the 20th century, planned and executed by the Second Reich or Kaiserreich. A past that laid not only the foundation for racist theories and pseudoscientific medical experiments on humans – in this case Africans supposed inferiority was to be proven – but also produced, with its concentration camps in Africa, the blueprint for the later Nazi death camps. The way in which Germany tries to silence this past seems to prove Dr Theo-Ben Gurirab right when he assumes that the reason for this genocide not being discussed and treated like the Holocaust is mainly due to the fact that it was aimed against black people: ‘Germany apologised for crimes against Israel, Russia or Poland, because they are dealing with whites. We are black and if there is therefore a problem in apologising, that is racist.’

So we have good reasons from both perspectives – the African and the European – to get to know much more about this traumatic past, its continuity from slavery through colonialism to the Holocaust and Apartheid, and the way Germany and the other former colonial powers are dealing with it today.

Between 1904 and 1908 imperial Germany waged an atrocious and inhumane war of extermination against the Herero, Nama, Damara and San peoples in its former colony ‘German South West Africa’, now the Republic of Namibia. According to the criteria of the UN genocide convention of 1948, the atrocities and massacres committed by German troops must be qualified as genocide.

Only with Namibia’s independence in 1990 did it become possible for the descendants of the genocide victims and a free Namibian government to articulate with openness and self-determination their view on this history and to begin a process of dealing with this past. This includes the demand for ‘restorative justice’, which is fundamental for the further development of Namibia. It is morally important for the national process of reconciliation between the different peoples within Namibia and the descendants of German and other white settlers.

On a more material side, this subject is closely linked with the still unresolved question of land reform in Namibia and a situation that condemns the descendants of the victims of the German genocide to a life in bitter poverty. This is largely due to the fact that their land and cattle were stolen and given to white settlers mainly during the German colonial era. Apart from these economic disadvantages the uprooted people have to deal with a colonial mindset that is still preventing many from taking matters into their own hands in order to invent their future and that of their country.

Until today, the German Federal Government – which is the legal successor of imperial Germany – refuses to recognise and apologise for this genocide. There is some confusion on whether or not the words of apology expressed in 2004 by former Federal Minister Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul in Okakarara can be regarded as an official apology. At the centennial commemoration of the beginning of the 1904 genocide she stated: ‘The atrocities committed at that time would today be termed genocide – and nowadays a General von Trotha would be prosecuted and convicted. We Germans accept our historical and moral responsibility and the guilt incurred by Germans at that time. And so, in the words of the Lord's Prayer that we share, I ask you to forgive us our trespasses. Without a conscious process of remembering, without sorrow, there can be no reconciliation – remembrance is the key to reconciliation.’ Today it is more than clear and confirmed: the German Federal Government regards these words as a personal statement by the minister and does not adhere to them. An official apology is still lacking.

During 2011, it became known that the Berlin Charité Hospital was willing to restitute to the Republic of Namibia and its people 20 of the many thousands of mortal remains of victims of this genocide that are still locked in German archives and collections. For more than 100 years now, these human remains have been silently stored in the collections and archives of pathological institutes, universities and other German institutions, hidden like unwelcome witnesses of a denied past.

The great majority of these remains were looted and smuggled from the many German concentration camps in ‘German South West Africa’ for use in ‘scientific’ experiments aiming to ‘prove’ the racial inferiority of black people. ‘By using shards of glass,’ says the original subtitle of a contemporary photograph and prominent postcard motif, the skulls had to be ‘freed of flesh and made ready’ by the wives of those murdered before being sent off.

Being the first remains to be repatriated after more than 100 years, the delegation that came from Namibia to receive them was high-ranking. It included important representatives of the committees of the descendants of the victims, the Nama Technical Committee (NTC), the Ovaherero-Ovambanderu Council for the Dialogue on 1904 Genocide OCD-1904 and Ovaherero Genocide Committee (OGC), and it was headed by the Namibian Minister of Youth, National Services, Sports and Culture, Kazenambo Kazenambo.

Against all diplomatic rules and completely insensitive to the historic and emotional momentum of the event, the German government not only omitted to officially welcome the delegation, but also rejected participation in a podium discussion on 28 September 2011 and caused a scandal when Minister of State Cornelia Pieper – refusing like her predecessors to acknowledge the genocide and apologise for it in the name of the German nation and state – left the venue without even the decency to listen to the speeches of the Namibian delegation.

The months that followed this event were characterised by a steady decline in Namibian-German relations. The German ambassador to Namibia began to pour oil on the fire by making several derogatory public comments on the delegation’s supposedly ‘hidden agenda’ in Berlin. Two of the victims’ committees reacted sharply to this allegation and the issue was brought to discussion in the German parliament (Bundestag). Shortly after this a tête-à-tête between the German ambassador and the President of the Republic of Namibia, Hifikepunye Pohamba, ended on a ‘sour note’, the ambassador being shown the door for his insensitive and arrogant behaviour. Relations between the two countries had reached a temporary low point.

In the meantime Namibia went through some months of vivid public debate on how to deal with all the questions raised by the return of the skulls: the history, the reparation claims, the genocide, the need for unity among the Herero and Nama committees, the question of land distribution and land reform, and recently a debate on ‘tribal’ vs. national identity. This included reactionary comments in readers’ letters and articles published in the German-language Namibian newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung. The ‘culture of denial’ deliberately nurtured in these forums is discussed in an article by Melber and Kössler in this special issue.

Recently a motion was introduced in the German Bundestag, entitled: ‘Acknowledging the German colonial crimes in former German South West Africa as genocide and working towards restorative justice’. It comprises core issues and would mark a major step forward, if adopted. But the power relations in German politics will most probably prevent it from getting a majority when discussed and voted on 22 March 2012 – one day after Namibian Independence Day. Nonetheless, it has now become an important part of the debate and it would already be a strong symbolic move forward if all three current opposition parties – the Social Democrats, the Greens and Die Linke – would decide to vote in favour of it.

The aim of this special issue is to make a contribution to this debate by asking some renowned experts, activists, intellectuals, historians and journalists from both Africa and Europe to comment on the recent Berlin happenings as well as to share with a wider audience some important historical and political background information on the subject. Not all those we asked have had the time to contribute an article at this stage and we would also like to open this debate to an international audience especially on the African continent and in the African diaspora. Hence, we see this special issue as the start of a debate, not only about what happened in Namibia, but about German and European colonialism in general. Further articles and contributions on the mentioned topics are welcome.

Genocide in Namibia (1904-08) and its consequences

By Reinhart Kössler and Henning Melber

March 20, 2012 – Pambazuka News – From January 1904 the German colony of South West Africa (since 1990 the sovereign state of Namibia) seethed with the repercussions of the greatest resistance movement against colonial rule the country had yet witnessed. The colonial administration had been gradually implanted after the Berlin conference in 1884 which had sealed the partition of Africa among the European powers. A new brand of German radical nationalism began to echo the proverbial quest by the young Emperor William II for a ‘place in the sun’, calling for Germany’s establishment as a world power on a par with Britain, with a powerful fleet and an array of overseas colonies.

But Germany managed to grab only a few

colonies in Africa and Oceania after 1884, which turned out to be dismal

and costly commercial failures. Yet in nationalist circles, colonies

appeared indispensable to prove the country’s status as a world power.

Amongst the colonies acquired, Namibia was the only territory considered

suitable for extensive sett¬lement by Europeans. Settler ideology

envisaged the creation of a ‘New Germany’. Under such circumstances, any

challenge to colonial rule was tantamount to disparaging national

honour and grandeur. At the same time, the quest for settlement

translated into a sustained drive to expropriate Africans from their

lands and from their livestock.

The Herero–German war that began in early 1904 was the most formidable

challenge to colonial control once the formal subjugation of the country

had been completed. The Ovaherero had largely been able to keep

colonial encroachment at bay but the combined effects of the huge losses

of their herds through the rinderpest, a locust invasion, a malaria

epidemic and, above all, the consequences of the fraudulent practices of

traders which led to the sequestration of cattle and alienation of

land, plunged the Herero communities into crisis. Progressively,

alienated land was appropriated by settler farmers. Complaints were rife

about the Ovaherero, women in particular, being mistreated by the

colonists. Further encroachment loomed with the proposed railway, which

was to cut through the Herero heartland to reach the copper mines of

Tsumeb at its far north-eastern fringe. On either side of the railway, a

strip of European settlement was envisaged, thus to speed up further

land alienation and European settlement.

At the very beginning of the war, Paramount Chief Samuel Maharero (ironically promoted to such an invented new position by the colonial administration in return for earlier collaboration) gave strict orders to his followers not to attack women, children, missionaries, non-German Europeans or members of other indigenous groups. In January 1904 fighting spread rapidly (catching the authorities and settlers by total surprise), but Ovaherero fighters observed their leader’s instructions. While male farmers were frequently killed when their farms were attacked, as a rule, women, children and missionaries were escorted to the German forts. This did not prevent the spread of propaganda about horrendous atrocities committed by the Ovaherero. In their campaign, the Ovaherero initially succeeded in securing control of most of central Namibia, with only the German forts resisting the onslaught.

The colonial power started to pour in reinforcements, along with a new commander-in-chief, General Lothar von Trotha. He had earned his credentials as a member of the international expeditionary force that ravaged North China in retaliation for the Ihetuan (‘Boxer’) uprising in 1901 and, prior to that, by breaking African resistance, in particular that of the Wahehe, in then German East Africa, now Tanzania. From the beginning, von Trotha was quite outspoken about his mission. He considered the confrontation as a ‘war of races’. He claimed superior knowledge that ‘African tribes ... will only succumb to violent force. It has been and remains my policy to exercise this violence with gross terrorism and even with cruelty. I annihilate the African tribes by floods of money and floods of blood. It is only by such sowings that something new will arise which will be there to stay’ – meaning of course, German settlement of the country, thus devoid of competitors. This strategy was, despite the opposition of Leutwein, approved and endorsed by the army headquarters (General Staff) in Berlin. Under von Trotha’s command it was implemented faithfully.

Based on a mindset guided by a ‘total war mentality’ and extermination strategy, von Trotha was looking for a decisive battle. The military actions marking a turning point took place at Ohamakari (Waterberg) on 11 August 1904. The Ovaherero had assembled there as a people, men, women and children, with their herds of cattle. After the military encounters, the majority of Ovaherero broke through the German encirclement in an easterly direction, going into the waterless Omaheke – a vast dry land with no surface water, bordering on Bechuanaland (today Botswana). To this day, historians are not agreed whether this was actually a military victory for the German colonial army. In any case, to secure a final and decisive victory, units of German soldiers followed the fleeing Herero in hot pursuit, cutting off access to waterholes and poisoning those they came across. More than seven weeks later, on 2 October, von Trotha proclaimed his infamous extermination proclamation and publically called on his troops to ensure that the Herero would perish in the semi-desert: ‘Within the German borders,’ the proclamation stated (meaning the borders of German South West Africa), ‘every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot.’

The proclamation also stressed that neither women nor children would be spared; they would be denied refuge. While colonial apologists are eager to point out that an ‘internal’ order by von Trotha instructed the soldiers to shoot above the heads of women and children to force them to flee, they ignore that this command served the purpose, namely to chase them back into the waterless Omaheke to die of thirst and exhaustion. Their fickle indicator, intended to water down the extermination order and thus the intent to destroy, makes the actions an even more gruesome way of ‘exterminating the brutes’ (a phrase coined by Emperor William II in his speech when dispatching the soldiers to North China to mercilessly suppress the insurrection in 1901).

By today’s standards and in accordance with the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948, von Trotha’s proclamation was a purposeful order for genocide, as part of an overall strategy to secure the country for European, in particular German, settlement. The numbers of those who died a horrible death as a consequence of that order may never be fully ascertained. It is generally accepted that the various Herero groups might have numbered up to 100,000, of whom, according to some estimates, as few as 20,000 survived the ordeal. The concept of genocide, however, is not predicated on such number crunching. According to the UN convention of 1948, genocide is not defined by numerical dimensions but as ‘acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such’. That this was the imminent aim and character of the warfare conducted by the German colonial troops is borne out amply by the pronouncements of von Trotha and his superiors.

When the extermination order was eventually rescinded by the emperor, the genocide had already been perpetrated. Moreover, the official military account of the ‘Great General Staff’ in its concluding paragraphs summarised it as a major achievement of the war that the Herero nation was annihilated and had ceased to exist. It celebrated the prowess of the German troops. The late change of policy may be seen as the fruit of representations by missionaries who witnessed the carnage but also of heated public debate in Germany.

Thus, August Bebel, founder and parliamentary leader of the Social Democratic Party, worked strenuously to oppose budget appropriations for the colonial war and castigated von Trotha’s strategy as that of ‘a vile butcher’. Bebel reminded his audience of the emperor’s infamous farewell speech (as already quoted above) to the expeditionary corps sent to China when he called on the troops to act in ways to make a name for themselves in the same way the Huns did in Europe 1,500 years earlier.

Bebel surmised that there might have been a similar order given in private, ‘otherwise it would be wholly inconceivable for me that a general could issue such an order which contravenes all principles of martial law, civilisation, culture and Christianity’. The Catholic Centrist Party also questioned colonial policy at the time. On the government’s side, there were considerations of expediency: the genocidal strategy was cutting the ground from beneath the settlers’ feet by killing off potential labour power as well as the better part of the cattle herds of the Ovaherero which the settlers meant to appropriate for themselves. Paul Rohrbach, the commissioner for settlement affairs in German South West Africa, bemoaned after the war that the workforce, urgently required as the most important asset for building the colonial economy, had short-sightedly been destroyed.

Nama resistance

On 4 October 1904, things took a new turn with the start of the Nama-German war in southern Namibia. This was probably occasioned by witnessing the fate meted out to the Herero. The various Nama groups avoided a large-scale battle and managed to hold out much longer than the Ovaherero. General von Trotha responded by transferring his strategy of genocidal suppression to this region as well. His proclamation to the Nama explicitly cited the Herero experience. Larger Nama groups capitulated after Hendrik Witbooi, by now an octogenarian, died in action more than a year after the commencement of the uprising, but some carried on until 1908.

Those who gave themselves up to the Germans met a similar fate to the surviving Herero. Contrary to earlier promises, they were made prisoners. Men, women, children and elderly people, indiscriminately, were detained in concentration camps. They shared this fate with the surviving Ovaherero. These concentration camps were located largely in the relatively cold and moist climate of the two port towns of Swakopmund and Lüderitz. Unaccustomed to these conditions, underfed, ill-clothed and badly accommodated, thousands of prisoners died from sheer neglect, or from their exertions as forced labour. Even after the war had officially been terminated, groups of Nama were transported to other German colonies in Africa, Togo and Cameroon. Of these groups of deportees, many also died before they were repatriated shortly before the beginning of World War I. It is estimated that of more than 20,000 Nama who lived in southern Namibia before the uprising, less than 10,000 survived these various forms of savage repression.

One of the more appalling features of this mass destruction of human lives is the kind of open publicity the perpetrators may be said almost to have revelled in. Picture postcards were produced displaying in particular the concentration camps. The term concentration camp emerged shortly before the turn of the century during the Spanish-American war on Cuba and got wider currency in the course of the Anglo-Boer war in South Africa, when British strategy employed such guarded camps to defeat settlers of Dutch origin. While the term did not carry quite the same meaning it acquired through the Nazi Holocaust some 40 years later, the element of destruction both in South Africa and Namibia was quite obvious and undeniable. The postcards from the German colony show an appalling disregard for human suffering, which could be conveyed, as it were, as a greeting to one’s loved ones at home. The same is true of colour pictures showing scenes of prisoners being hanged, or of forced labour scenes representing ‘native life’ as though this was a quasi normal feature in the lives of the so-called natives – as if it were natural for Africans to be subjected to inhuman treatment and the regular application of brute force.

The recent repatriation of human skulls has focused attention on the ways in which the German public of the early 20th century was informed, including about the transportation of human remains from the colony to the metropole. One image, reproduced on postcards and in book illustrations, shows soldiers packing a crate with human skulls with the caption that these had been cleaned of their flesh by Ovaherero women using shards of glass. Participants in the Namibian delegation who went to Berlin in September 2011 to receive the skulls also recalled stories they had heard from their parents and grandparents who had gone through these ordeals. In Germany, these skulls became the material upon which academic careers were built. Such racial science became a mainstay of Nazi ideology and discriminatory practices.

In other respects as well, this first genocide of the 20th century may arguably be considered to be one of the most publicised by the perpetrators themselves. There were popular novels, books of reminiscences and literature filled with colonial propaganda, all of which extolled the exploits of the German troops. In line with sentiments that recent research has traced amongst German soldiers involved in the mass murders during World War II, this literature conveys praise for the hardship valiantly endured whilst killing not only opponent fighters, but old people, women and children. The experience of the colonial genocide in Namibia, therefore not surprisingly, eventually fed into Nazi ideology and propaganda. The most popular novel on the ‘civilising mission’ of exterminating the Herero, originally published in 1906, was ‘Peter Moors Fahrt nach Südwest’ by Gustav Frenssen. It attained a print run of over 400,000 copies and was reprinted for the last time in Germany by the German army headquarters for distribution in the trenches on the ‘Eastern Front’ in 1944, when it was referred to as Schützengrabenliteratur (Trench literature). In Namibia, stalwarts put out a new edition very recently.

The nationalist and colonial hysteria came to a head when incumbent Chancellor von Bülow used this atmosphere to engineer a grand political realignment (‘Bülow-Block’) and to organise an election campaign in 1907, still known in history as ‘Hottentot Elections’. By this means, Bülow managed to break the former majority of the Social Democrats and the Centre, and a centre-right majority was returned which ensured the passing of the budgets needed to further pursue the quest for world power.

Officially the military authorities declared the war terminated in March 1907, a timely move in the run-up to the elections mentioned above. But Ovaherero prisoners of war were released only at the end of May 1908, while Nama prisoners were never set free during German rule. In fact, deportation of Nama communities to Cameroon took place even after the formal end of the war. Moreover, the colonial administration pursued a grand design to further uproot the populations of central and southern Namibia, shifting Herero to the south, while transporting Nama to the centre, the northern portion of the whitesettlement zone.

Those survivors who were released found themselves in dramatically changed circumstances. Above all, they were expropriated of their land and their livestock. This meant the clearing of their land for settlement by white farmers and the appropriation of their herds in so far as they still existed. Moreover, Africans were legally barred from owning land and large livestock. In this way, Africans were systematically prevented from reconstructing a basis for an independent life for themselves, and Ovaherero in particular were prevented from resuming the symbolic rebuilding of their communities, which largely hinged on cattle herds. In terms of the UN genocide convention, measures to break up and destroy the communal life of the target group or, as in this case, to systematically prevent its reconstruction, also amount to an act of genocide. Furthermore, Africans were forbidden to settle in large groups, even when employed on a settler farm, and above all, they were subjected to a strict obligation to enter into waged labour which was subjected to comprehensive administrative control.

To ensure the smooth and comprehensive working of this system and to foreclose any new attempt at rebellion, all Africans over seven years of age were subjected to a labour obligation, registered and required to carry a token, the so-called pass mark (Passmarke) around their necks. This token has turned into a much sought after collector’s item, a dubious modern kind of ‘memory culture’. In its time, the token served as the means by which any white person could check to make sure that the African was entitled to be in any particular place and otherwise could be turned over to the police. To this was added a system of strict racial segregation. The systematic discrimination was linked to harnessing the labour power of dispossessed Africans in the interests of the new colonial economy, centred on white settlements. The Native Ordinances, strictly regulated and ruthlessly enforced after 1905, in many ways presaged what four decades later would be called apartheid.

Dealing with the past

Why is it so important to commemorate genocidal atrocities such as those committed in Namibia early in the 20th century today? There are a number of reasons, which may be understood if grouped with two interrelated trajectories. The first of these trajectories is that, despite the ongoing tendency towards denialism, the Namibian genocide is an integral part of the development of political society and culture in Germany. The second trajectory concerns the overall dynamic and logic of genocide as it unfolded during the entire course of the 20th century. The distinction between these two trajectories also relates to the hotly debated issue of the exceptionality of the Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany against European Jewry as well as against groups such as the Sinti and the Roma. This also leads to the further issue, whether the wars and mass crimes emanating from the German state during the first half of the 20th century are rooted in some specifically German path of historic development, fundamentally different from the West.

In brief, it may be said that the Namibian genocide contributed towards establishing a specific routine among the German military and also amongst civilians and the way they looked at war and specific acts of war. This meant, in particular, seeing the enemy not as another human being but as a member of an alien, inferior race, that is best annihilated, like ‘vermin’, in the language of the Nazis. Or, in more recent terminology, like ‘cockroaches’ or ‘rats’. Dehumanising whole groups or categories of humans in this way is widely considered an important precondition for actors to perpetrate mass killings, be it in direct personal confrontation with the victims or in the seemingly abstract settings of saturation bombing and even more in today’s cyber wars where soldiers no longer have to face or see those they are killing. In very different ways, all those situations are structured to shield the perpetrators from fully confronting the implications of their murderous acts.

In a colonial situation as it prevailed in Namibia in the early 20th century, the negation of the full human worth of the persons of the colonised is predicated in the structurally racist set-up of colonialism. This is even more the case when the aim of colonial rule is not simply control and exploitation of the country, its resources and inhabitants, but rather, settlement by members of the colonising society. The inherent racism of settler colonialism has worked to lower the threshold of mass killings in appalling ways in many cases and is to be found particularly in the Americas, Australia and southern Africa. In the Namibian case, this links up with the more specifically German trajectory, when we observe continuities of this in accounts and novels read by a mass readership, of military practice as well as in the activities of specific persons, and in military doctrines and routines that link strategic ideas of decisive battles to the concept of final solution and extinction of the enemy.

Such concepts of brute force had an incubation period in the German colonies. While use is made here of the example of German South West Africa, the extermination strategy used in German East Africa in response to the Maji Maji rebellion, triggered in 1905, where the policy of scorched earth was applied, should not be forgotten. Famine was used as a deliberately created weapon, as a result of which an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 people were starved to death. In 1905 one of the leaders of German troops in the colony, Captain Wangenheim, wrote: ‘Only hunger and want can bring about a final submission. Military actions alone will remain more or less a drop in the ocean.’ Such a mindset was fertiliser, if not the seed, for the reactionary ideology of selection based on the claim of the superiority of the Aryan race emerging during the Weimar Republic among those who constituted the Nazi regime, and which culminated in the Holocaust perpetrated in the 1940s.

It has to suffice here merely to mention these problems. Another dimension concerns active remembrance. Here again, it is appropriate to refer to the German case where a specific form of public repentance and remembrance may be said, at least in retrospect, even to have been incorporated into the founding myth of the second German republic. Even though anti-Semitism unfortunately even today is not a thing of the past, also in Germany, and despite the initial post-war tendency of denialism, the insistence by a younger generation since the 1960s has born fruit: the Holocaust is the object of regular remembrance on the part of officialdom as well as civil society, bordering on a cult of mea culpa, denying any critical engagement with radical Zionism and the Israeli policy of occupation and Apartheid, which is all too easily accused of and stigmatised as anti-Semitism.

It should be noted, however, that such late but eager remembrance and repentance, along with the – always and necessarily completely inadequate – material redress associated with it, has been halting and highly selective. Former forced labourers from Eastern Europe have been indemnified, on a rather paltry scale, more than 50 years after the end of World War II, and this could only be achieved by a combination of persistent civil society action in Germany and the German corporations fear of incurring law suits in the United States. Other victim groups managed to secure some kind of compensation even later.

In the case of the Namibian genocide, consecutive German governments, regardless of their political hue, have consistently evaded a formal, official apology. This has been declined on the grounds that this might constitute an argument for the descendants of the survivors to sue for damages. In ignominious ways, state visits to independent Namibia have contrasted a cordial relationship with German-speaking Namibians (among them many who continue to consider themselves as ‘South Westers’) but dealing short shrift when called upon to respond to the consequences of colonial genocide. It must be said that the former minister of economic cooperation and development, social democrat Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, stands out strongly by actually offering an apology in her speech at the central commemoration of the centennial of the battle at Ohamakari on 14 August 2004.

However, subsequent experience has shown that this was a somewhat personal rather than an official act – even though today German officials sometimes claim that Wieczorek-Zeul has apologised and that thereby the chapter could be conveniently considered as closed. The contrary is borne out generally, by the so far unsuccessful quest of Namibian victim groups to reach a dialogue with German officials, and of course more specifically by the way the German government (mis)treated the Namibian delegation who had come to Berlin for the repatriation of the skulls in September 2011.

There are powerful symbolic ways for the admission of (historical) guilt, devoid of any glamour and pompous ceremonial rituals. They can be public and dignified at the same time, and have a lasting wider impact. The bent knees and bowed head of the then German Chancellor Willy Brandt in front of the Warsaw War Memorial certainly was such an act. There are other ways of making less public gestures of reconciliation, followed by practical policies.

One central demand, which the German government’s behaviour in the genocide question has demonstrated by default, is first and foremost to listen to the victim groups, instead of decreeing what must be done. The exact modalities of remembrance and redress may be subject to debate but there is a responsibility and obligation to stand up, also through scholarly endeavour, against the clamorous calls for doing away with the past by a final stroke, thus repressing and, in the words of Theodor Adorno, ‘defraud[ing] those murdered even of that only gift with which we, powerless, are able to provide them: remembrance’.

[Reinhart Kössler is a social scientist, working at the Arnold Bergstraesser Institute in Freiburg and teaching political science at the University of Freiburg. Besides his academic pursuits, he has been involved for a long time in a wide range of civil society initiatives in Germany, mainly centering on Third World issues and with a long-standing focus on southern Africa. Henning Melber came to Namibia as a son of German immigrants in 1967 and joined Swapo in 1974. He was director of the Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit in Windhoek from 1992 to 2000, and research director at the Nordic Africa Institute in Uppsala, Sweden (2000–06), where he is executive director of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation since then. He is a research associate with the Department of Political Sciences/University of Pretoria.]

![]()

This work is posted under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.