Global post-fascism and the war in Ukraine

First published at Posle.

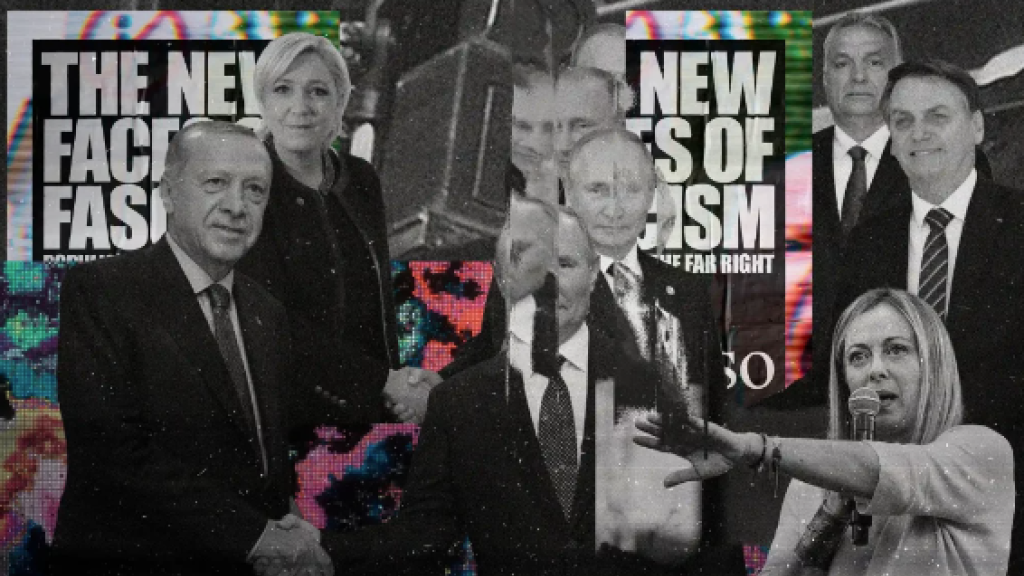

A conversation between Ilya Budraitskis and historian Enzo Traverso about the global rise of post-fascism, Putin’s Russia, and the war in Ukraine.

Ilya Budraitskis: A few years ago, you wrote The New Faces of Fascism, where you defined post-fascism as a new threat that is simultaneously similar to and different from classical fascism of the 20th century. Post-fascism, as you describe, grows out of the fundamentally new soil of neoliberal capitalism, in which labor movements and forms of social solidarity have been attacked. You emphasize that post-fascism grew out of post-politics as a reaction to technocratic governments that ignore democratic legitimacy. At the same time, your analysis is limited mainly to the European Union and the United States, where fascism results from liberal democracy. Can this approach be expanded to the transformation of authoritarian regimes like the one in Russia, especially after the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine? In Russia, the regime in the first decade of its existence in the early 2000s also presented itself as a technocratic post-political government. It was based on mass depoliticization and lack of political participation in Russian society.

Enzo Traverso: Well, it’s important to emphasize that “post-fascism” is an unconventional analytical category. It’s not a canonical concept like liberalism, communism, or fascism. It’s rather a transitional phenomenon that has not yet crystallized or clearly defined its nature. It can evolve in different directions. Nevertheless, the starting point of this definition is that fascism is trans-historical, transcending the historically framed experience of the 1930s. Fascism is a category that can be useful to define political experiences, systems of power, and regimes that take place after the period between the two world wars. It’s common to speak about Latin American fascism during the military dictatorships of the 1960s and the 1970s.

That said, when we speak of democracy, it is worth noticing that although Germany, Italy, the United States, and Argentina share this label of liberal democracy, this does not mean that their institutional systems are the same. Nor does it mean that they correspond with Pericles’ democracy in Ancient Athens. So, fascism is a generic term that takes a trans-historical dimension. You are right to say that my book on post-fascism primarily focuses on the European Union, the United States, and some Latin American countries. When I wrote it, Bolsonaro had not yet come to power in Brazil. However, I also wrote that post-fascism could be considered a global category, which tendentially includes authoritarian political regimes such as Putin’s Russia or Bolsonaro’s Brazil. I am not sure that this category can be used to define Xi Jinping’s China, simply because this regime was created by the communist revolution of 1949 (I similarly do not think we could describe Stalin’s Russia as “fascist”). Maybe this category can be used to depict some tendencies that shape Modi’s India or Erdogan’s Turkey and raise legitimate worries. But I do not suggest extending or transposing my analysis of Western Europe to other continents and political systems; I would rather say that Western European post-fascism can be located into a global post-fascist tendency, including regimes with entirely different historical trajectories and pasts. Otherwise, it would be a very problematic way of creating for the umpteenth time a Eurocentric paradigm of fascism, which is not my approach.

The problem of how to define post-fascism, however, still remains after these considerations. Global post-fascism is a heterogeneous constellation in which we can find shared features and tendencies. They are nationalism, authoritarianism, and a specific idea of “national regeneration.” Within this constellation, these tendencies might appear differently combined and in varying degrees. For instance, Putin’s Russia is much more authoritarian than Meloni’s Italy. In Italy, we have a chief of government who proudly claims the fascist past (her own and that of her country), but Italy’s dissident voices are not censured, persecuted, or put to jail like in Russia. There are no Italians who are exiled because their lives are threatened in Italy. This is a significant qualitative difference. Another relevant difference is the relationship to violence. We are speaking about Russia, which is a country involved in a war. The violence displayed by this variety of post-fascist regimes cannot be compared.

There are a lot of relevant discrepancies distinguishing all these forms of post-fascism from classical fascism. Their ideologies and their ways of mobilizing the masses are not the same… The utopian dimension, for instance, which characterizes classical fascism, is utterly absent from current fascism, which is very conservative. We could mention other cleavages.

Ilya: I would like to go through these features of post-fascism. If I understand you correctly, after reading the book and some of your interviews, you stress that post-fascism came from the crisis of democracy. Democracy not as a normative term, but electoral politics, to be more precise. The difference between classical fascism and post-fascism is that the latter does not challenge democracy. Classical fascism had the task of overthrowing democracy. Post-fascism still tries to use electoral mechanisms. The transformation towards an openly fascist dictatorship should take place through legal institutions. I am interested, in particular, in this moment of transition. You also write in your book that post-fascism can be understood as a stage for the new quality of political regimes with authoritarian or dictatorial features. How do you think this transition differs in different regions? I believe that in Russia fascist tendencies developed from the top. Twenty years ago, elements of the authoritarian regime were already installed, and since then Russia has been transformed into some kind of fascist dictatorship.

Enzo: A straightforward historical overview shows that many authoritarian regimes with fascist features have appeared without mass movements, but were introduced through a military coup, for instance Franco’s regime in Spain or Latin American regimes in the 1960s and the 1970s. They were not supported by a mass movement unlike the canonical examples of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Both Mussolini and Hitler were appointed to power by the King (of the Italian monarchy) and by the President (of the Weimar Republic) respectively, according to their constitutional prerogatives. I don’t think that we can create a compelling or normative fascist paradigm. It is a large category including different ideologies and forms of power.

An enormous difference that separates post-fascism from classical fascism is the huge transformation that has taken place in the public sphere. At the time of classical fascism, charismatic leaders had an almost physical contact with their community of followers. Fascist rallies were liturgical moments that celebrated this emotional communion between the leader and its disciples. Today this connection has been replaced by the media, which create a completely different kind of charismatic leadership, at the same time more extended and pervasive, but also more fragile. Nonetheless, we cannot avoid the fundamental question: What does fascism mean in the twenty-first century? All observers constantly face this question: Is Trump/Putin/Bolsonaro/Le Pen/Meloni/Orban fascist? The simple fact of putting this question means that for us it is impossible to analyze all these leaders or regimes without comparing them to classical fascism. On the one hand, they are not fascist tout court; on the other hand, they cannot be defined without being compared with fascism. They are something between fascism and democracy, oscillating between these two poles according to the changing circumstances.

There are also contradictory dynamics. Russian nationalism is going through a process of radicalization, reinforcing these post-fascist tendencies. In Western Europe, the Italian case is emblematic of the opposite tendency. Until very recent times, Georgia Meloni was the only political leader who shamelessly claimed her fascist identity in the Italian parliament. In this she differed from other far-rights in Europe, for example Marine Le Pen, who had explicitly abandoned the ideological and political models of her father by changing the name of her movement (Rassemblement National replacing Front National). Marine Le Pen claimed her belief in democracy, affirming her support to the institutions of the French Republic, and so on, when Meloni celebrated the accomplishments of Mussolini’s Italy. The latter won the elections — thanks to a favorable electoral system and the division of the center-left — not because of her ideological references but rather because she appeared as the only and most coherent adversary of Mario Draghi, the chief of a governmental coalition supported by the European Union.

However, since she came to power, Meloni is conducting the same policies of her predecessor and no longer criticizes the EU institutions. As chief of government, she celebrated the anniversary of the Liberation, the anniversary of the triumph of democracy over fascism that took place on April 25, 1945. Meloni reminds me of those paradoxical figures that, in the 1920s, were called in Germany Vernunftrepublikaner (“republicans by reason”). After the collapse of Wilhelm’s Empire at the end of 1918, they had accepted — by reason — the democratic institutions of the Weimar Republic, but their heart still beat for the empire. Italian post-fascists are a similar case, one century later. They do not wish to install a dictatorship or to dissolve the parliament, but emotionally and culturally speaking they remain fascist. Their fascism requires many adjustments to a changed historical context.

There is also the case of Trump. In 2016, he was a worrying and enigmatic political innovation. During his presidency, and particularly on January 6, 2021, we experienced a significant political turn that revealed a clear fascistic dynamic. Today I am not sure that the Republican Party, that was one of the pillars of the US establishment, can be defined any more as one of components of the American democracy. It is a political party in which very strong post-fascist or even neofascist tendencies have become hegemonic, a political party that puts into question the state of law and the most elementary principle of democracy: the alternation of power through elections.

Ilya: I hypothesize that in countries with a limitation of political power because of oppositional political movements or various state institutions which reduce the power of the president or prime minister, the transformation towards an authoritarian state is more complicated. Whereas in Russia, all the political institutions have lost any source of independence (no parliament, no court, no serious political opposition), and there are no limitations to the actions of the president, the only sovereign. In countries like the US, the president has many obstacles to his independent decision-making and setting of policies, and the president’s decisions are not totally decisive.

Enzo: I agree with you. I am far from idealizing liberal democracy and market society, but there is undoubtedly a difference between the United States, where democracy has existed for two and a half centuries, and Russia, where it has almost never existed. We do not need to mobilize Tocqueville to explain this. In Russia, democracy is the legacy of a few years of Glasnost and Perestroika, at the end of the USSR, as well as a byproduct of the resistance of civil society against an oligarchic power that managed the transition to capitalism three decades ago.

However, there remains a cleavage between the new radical right and classical fascism that should also be considered: the relationship of post-fascism with neoliberalism, as you said at the beginning of our conversation. My book suggests that one of the keys to understanding the post-fascist wave in Western Europe is its opposition to neoliberalism. Of course, as the case of Meloni proves, it is a very contradictory opposition. They win elections because they oppose neoliberalism, but when they come to power, they apply neoliberal policies. Italy is a great example. Neoliberalism is embodied in Western Europe by the European Union, the European Commission, the Central European Bank, etc. Those institutions are trusted interlocutors for the financial elites, who can (also?) find a compromise with Marine Le Pen, Giorgia Meloni or Victor Orban, without trusting them completely. Emmanuel Macron, Mario Draghi, and Mark Rutte are much more reliable and trusted leaders.

In the US, one key to understanding the Trump election in 2016 was his opposition to the establishment. Hilary Clinton embodied the establishment much more than Trump did, despite the obvious fact that a powerful section of American capitalism supports the Republican Party. Nonetheless, there is an evident tension between Trump — sometimes an opposition — and the most significant elements of neoliberalism. Think of the very bad relationship between Trump and California’s multinational companies, new technologies, and so on. There is also an almost “ontological” or constitutive discrepancy between neoliberalism, which works through the global market, and post-fascism, which is deeply nationalist. Post-fascists demand state interventions and protectionist tendencies that contradict the logic of financial capitalism.

Ilya: My next question is related to what you just said about current capitalism’s neoliberal transformation. You mention in your book that one of the differences between post-fascism and classical fascism is the lack of a project for the future. While classical fascism was a modernist project with a vision of another society (opposite to any emancipatory socialist perspective), post-fascism has no consistent project, only a no-horizon view. There’s an idea that we have to go back to some beautiful past without any vision of the future. This reminds me of one of the main features of neoliberalism. There’s no future, no alternative. Capitalist realism is dominant, as Mark Fischer once pointed out. Another feature is the temporal experience of the post-fascist leaders. People like Putin and Trump are older people. Classical fascism was mostly the movement of the young. Do you think this lack of the future and retrospective, nostalgic element of post-fascism somehow relates to the neoliberal lack of view on the future?

Enzo: You point out some relevant issues. Classical fascism possessed a powerful utopian dimension. It wanted to be an alternative to both liberalism and communism, but it even strived to be a new civilization, something related to a different conception of existence itself. They launched very ambitious projections of society: the myth of the new man, the myth of the “thousand-year Reich,” and so on. This utopian dimension was rooted in the depth of the European and international crisis of capitalism. It does not exist today because capitalism in its neoliberal form appears as an insuperable and indestructible framework. Between the two world wars, there was an alternative to capitalism, created by the Russian Revolution, and communism as a utopian project was able to mobilize millions of human beings. This is a huge difference. Contemporary post-fascist currents are extremely conservative. They wish to save traditional values. They want to return to the traditional idea of a nation, conceived as a cultural, religious, and ethnically homogeneous community. They wish to restore the Christian values on which the history of Europe was built. They want to defend national communities against the invasion of Islam, immigration, etc. They wish to protect national sovereignty against globalism. This does not remind us of the fascist utopianism or Nazi Germany, much more of the German “cultural despair” (Kulturpessimismus) of the end of the nineteenth century.

Post-fascism is reactionary, and as such it is a reaction to neoliberalism, which does not wish to come back to national borders and sovereignties. Neoliberal historical temporality is “presentist,” not reactionary. It posits an eternal present that absorbs both past and future: our lives and society must run and can be destroyed if they don’t fit the compelling rules of capital development, according to a temporality rhythmed by the stock exchange, but the general framework of capitalism is immutable. Capitalism was “naturalized,” and this is probably the major achievement of neoliberalism. Post-fascism is an illusory alternative to neoliberalism, just as fascism often depicted itself as “anti-capitalist”; but the difference is that today the ruling classes do not choose this fake alternative. Their institutions are not so deeply unsettled to accept such an option.

The same can be said about its expansionism. Italian fascism wished to conquer new colonies; Nazi Germany wanted to conquer the entire continental Europe. Today’s post-fascism is very xenophobic and racist, but its xenophobia and racism are defensive. They say: we must protect ourselves against the threat embodied by the “invasion” of non-white and non-European immigrants. We are not going to conquer Ethiopia; we are going to protect ourselves from Ethiopian immigration. The comparison between Putin’s aggression of Ukraine and the fascist or Nazi conquests in Europe does not work because Putin’s expansionism wishes to recreate the Russian Empire in Central Europe by reintegrating a country that Russian nationalism has always considered its own vital space, culturally belonging to Russian history. But the Ukrainian war, if we can make a counterfactual comparison, is as if the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 had been stopped in two weeks and the Wehrmacht had to give up occupying Warsaw.

Ilya: I agree that Hitler was much more successful than Putin.

Enzo:The nature of expansion is not the same. The Nazi aggression against Poland was imperialistic and expansionist; the Russian aggression of Ukraine is revanchist and “defensive,” especially considering Kiev’s goal of joining NATO. There are also some relevant demographic differences. In the 1930s, Nazi Germany had, like Russia today, suffered a significant loss of territories and population, but its population was dramatically growing. As for Italy, its population grew despite a structural emigration that weakened its economy. If today Putin embodies an illusory nationalist response to the collapse of 1990, it is also because his defensive expansionism is not supported by a powerful demographic dynamic. Russia is declining and struggling to preserve its status as a superpower. Of course, it has some advantages: nuclear weapons and so on. But economically and demographically speaking, its radicalized nationalism is defensive.

But let me add a last consideration on neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is not only a set of economic policies: free market, deregulation, global economy. It is also an anthropological model, a conduct of life. It is a philosophy and a lifestyle based on competition, individualism, and a particular way of conceiving human relations. In the twenty-first century, this anthropological paradigm has been imposed on a global scale. This means that all post-fascist movements are rooted in this anthropological background. This explains why there are so many significant changes compared with classical fascism. First, we have powerful post-fascist movements led by women. This would have been inconceivable in the 1930s. Second, the movements must accept certain forms of individualism, individual rights, and freedoms. Their Islamophobia, for instance, is sometimes formulated as a defense of Western values against Islamic obscurantism. This way, while post-fascism opposes neoliberalism, it is simultaneously rooted in its social structure.

Ilya: You have mentioned that one of the primary emotions of post-fascism is the defensive line. In fact, the whole war in Russia was presented by the official propaganda as a defense not just against NATO but also fake values, especially the infiltration of LGBT and gender politics. In this sense, one can say that in this kind of regime, the borders between international politics and domestic politics are blurring. However, we can also see that the neoliberal mindset you have just talked about dominates all explanations of the international situation. Of course, Putin is very much preoccupied in his political imagination with the role of Russia in the global arena. Still, Putin and other Russian officials explain that international relations are a kind of market where you have competition, where the same self-interest paradigm is defining the position of states, where the multipolar world that they advertise instead of American hegemony is the true free market against monopoly. They see the world as the US’s monopoly, which should be challenged by true, honest, fair competition of multiple strong players. How do you see these relations?

Enzo: I am not well equipped to answer this question satisfactorily. Of course, the tenacious and admirable resistance of Ukraine against Russian invasion deserves to be supported, both politically and militarily. I don’t agree with the currents of Western left that denounce Russian aggression and simultaneously refuse to send weapons to Kiev. This seems to me a hypocritical stance. The Ukrainian Resistance is conducting a national liberation war that is forcefully plural and heterogeneous. Like all Resistance movements in Europe during the Second World War, it includes right- and left-wing currents, nationalist and cosmopolitan sensitivities, authoritarian and democratic tendencies. Between 1943 and 1945, the Italian Resistance gathered a large spectrum of forces, going from the communists (the hegemonic tendency) to the monarchists (a small minority), and passing through social-democrats, liberals, and Catholics. In France, Resistance had two souls — De Gaulle and the communists — beside which there were also fighting Catholics, Trotskyists, and a constellation of small (but very effective) organizations of anti-fascist immigrants from Central Europe, Italy, Spain, Turkish Armenia, etc. This diversity is inevitable in a national resistance movement.

Having said that, I am quite pessimistic about the outcome of this conflict. If Putin wins, which is improbable but not impossible (particularly in case of an involvement of China on his side), this will have tragic consequences not only for Russia and Ukraine but also on a global scale. Fascist and authoritarian tendencies will be reinforced in Russia; post-fascist tendencies in Europe and internationally will strengthen equally. On the other hand, a Russian defeat, which is desirable, would mean not only the affirmation of a free and independent Ukraine but also, very probably, an extension of NATO and the US hegemony, which is much less attractive.

The Ukrainian war is often depicted as an entanglement of conflicts: a Russian invasion which is an inacceptable aggression; a self-defense war of Ukraine which wants to be supported; and a Western indirect military intervention which the US aims at transforming into a NATO proxy war. Ten years ago, there was a civil war in Ukraine, which created some premises for the current conflict. This is a very complex situation, in which the left needs to be nuanced. Whereas in Russia we must struggle against Putin and in Ukraine we must struggle against the Russian invasion; in the US and the EU countries we cannot support an extension of NATO or the increase of our military budgets.

This situation is not completely new. During the Second World War, the Resistance movements and the Allied armies fought together against the Axis powers, but their convergence was limited, and they did not share the same final goals. This became evident in Greece, where the collapse of German occupation threw the country into a civil war in which the British army helped to repress the communist Resistance. Tito and Eisenhower struggled together against Hitler, but their objectives were not the same. Today, we are in this whirl of contradictory tendencies: on the one hand, we must support the Ukrainian Resistance, as well as the dissident voices in Russia; on the other, we must be able to say that a neoliberal order is not the only alternative to post-fascism. The left should be able to speak to the non-Western countries that did not condemn this invasion. The Western left should prove that it is possible to fight against the neoliberal order without being the friends of Putin.

Ilya: My last question is about anti-fascism. You wrote that anti-fascism as a tradition and a view, was lost in recent years, and you believe that the re-establishment of the anti-fascist tradition could be the only proper answer to the rise of fascism. However, this also means that the anti-fascist tradition should be reinvented, it cannot be the same movement it was in the middle of the twentieth century. Of course, there are a lot of difficulties with this tradition. For instance, the Russian invasion of Ukraine was also labeled as anti-fascist (against the Ukrainian “Nazis”) by Russian official propaganda. Of course, the idea of anti-fascism was devalued from various sides. What can this reinvention of anti-fascism look like?

Enzo: Again, it is difficult to answer this question. I depicted post-fascism as a global phenomenon, but I am not sure we can speak of global anti-fascism. It depends on contingent circumstances. Of course, we can say that fascism is bad everywhere at any time, but anti-fascism does not have the same meaning and political potentialities everywhere at any time. I do not know how anti-fascism can be perceived today in Russia, India, or the Philippines. Different countries have different historical trajectories, and anti-fascism cannot be understood and mobilized in the same way everywhere. In Western Europe, anti-fascism means a specific historical memory. In Italy, France, Germany, Spain or Portugal, in countries that experienced fascism, with shared collective memories, it is impossible to defend democracy without claiming an anti-fascist legacy. In India, for instance, the relationship between the struggle for independence and anti-fascism is much more complex. During the Second World War, being anti-fascist meant renouncing, at least for a while, to the struggle for independence. In Russia, Putin endorses a demagogic rhetoric by depicting the invasion of Ukraine as the final stage of the Great Patriotic War. Of course, demystifying this lying propaganda and re-establishing the true significance of anti-fascism is crucial for Russian democrats and dissidents. In Ukraine, things are more complicated because the fight against Russian oppression is older than anti-fascism and was not always anti-fascist. The history of Ukrainian nationalism includes a fascist and right-wing component which cannot be forgotten. At the same time, the memory of anti-fascism is that of an anti-Nazi war — as epic and heroic as it was tragic — that Ukrainians fought as part of the USSR. Therefore, being anti-fascist means claiming a tradition that is not consensual in Ukrainian history. It means to defend a certain political identity within a plural Resistance movement. Things are incredibly complicated. Roughly speaking, we could say that anti-fascism means a free and independent Ukraine not opposed to but rather allied with a democratic Russia. Unfortunately, this will not happen tomorrow.