Kissinger, Mao and the undermining of the 1960s revolutions: Recalling Raya Dunayevskaya’s prescient analysis

First published at The International Marxist-Humanist.

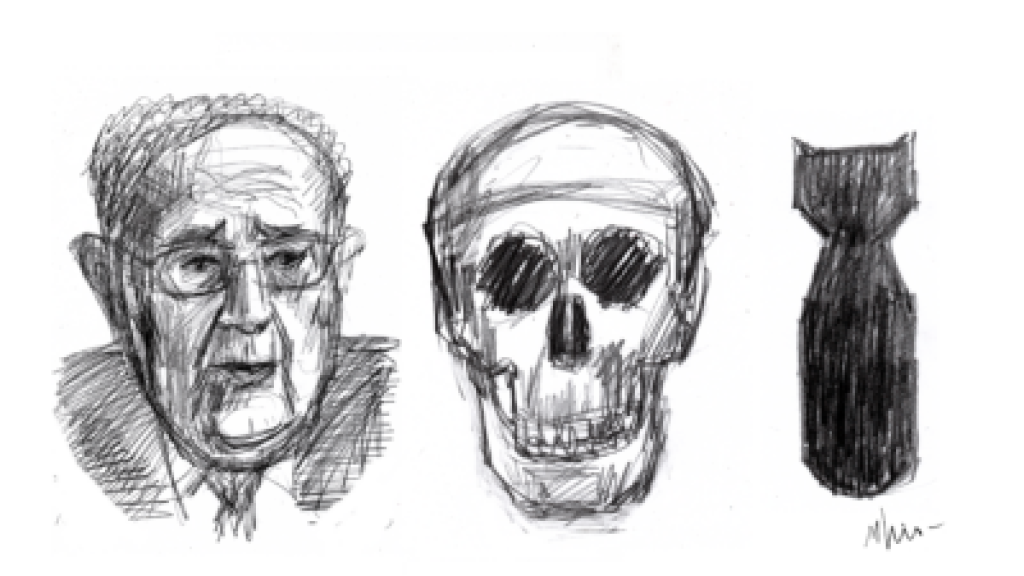

The war criminal Henry Kissinger, who died at 100 in December, has been celebrated as a skilled strategist of the U.S. empire, especially for his — and the equally criminal Richard Nixon’s — China diplomacy, which brought that country back into the web of great power alliances and competition in the early 1970s. At the same time, even moderate liberals have deplored Kissinger’s utterly cynical Realpolitik and its human cost, though usually concluding that the results were more positive than negative overall. These assessments of Kissinger also absolved him of involvement in Nixon’s attempt to install an authoritarian regime at home, usually dubbed the Watergate “scandal.”

The Left has of course been far harsher, recalling the mass deaths Nixon’s and Kissinger’s policies wrought during the 1960s-1970s: utterly inhuman bombing campaigns during the Vietnam War against Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam itself (over 3 million deaths), complicity in Pakistan’s genocidal attempt to hold onto Bangladesh (3 million deaths, tens of thousands raped), and giving the go-ahead to Indonesia to invade and occupy East Timor (200,000 deaths). The Left has also noted Kissinger’s role in supporting the military coup that overthrew the democratically elected Marxist government of Salvador Allende in Chile, and the utterly brutal repression and deliberate impoverishment of the population that followed, in the first example of what came to be called neoliberalism.

The world situation in 1970-71

Despite this, few have dissected the real purpose and consequences of the China “opening” that Nixon and Kissinger orchestrated, beginning in 1970-71. To do so properly, one needs to recall that, even though the global revolutionary wave had crested in 1968, the early 1970s continued to experience turmoil and revolutionary ferment across the world at a level not seen since the end of World War II: the U.S. and global antiwar movements were continuing as was the unrest against racism, both in the automobile factories and inside the U.S. armed forces themselves; the Vietnamese national liberation struggle was winning against U.S. imperialism; Chile and other Latin American countries were moving to the left; the Russian empire was still feeling the ferment of the 1960s, as seen most recently in the Poland’s worker unrest of January 1970-71; China was still coping with Mao’s disastrous Cultural Revolution, not only its economic and social destructiveness, but also how independent worker and student Marxist revolutionaries like Sheng Wu-lien had emerged in its wake; in addition, the long period of economic growth that began across the industrialized countries after World War II was coming to an end.

Long ago, Friedrich Engels described what the rulers were facing during his own time, in the aftermath of the 1848 revolutions: not only rivalries among the five great powers of the time but also the threat emanating from the “sixth power,” that of the revolution, crushed but smoldering underground:

But we must not forget that there is a sixth power in Europe, which at given moments asserts its supremacy over the whole of the five so-called ‘Great’ Powers and makes them tremble, every one of them. That power is the Revolution. Long silent and retired, it is now again called into action by the commercial crisis, and by the scarcity of food. From Manchester to Rome, from Paris to Warsaw and Pesth [part of Budapest], it is omnipresent, lifting up its head and awakening from its slumbers. Manifold are the symptoms of its returning life, everywhere visible in the agitation and disquietude which have seized the proletarian class. A signal only is wanted, and this sixth and greatest European power will come forward. (New York Tribune, Feb. 2, 1854, in Marx-Engels Collected Works 12: pp. 557-58)

As has been seen time and again, great powers often come together, putting aside some of their competition, when faced with Engels’s “sixth power.” And that is exactly what happened in the early 1970s. However, orchestrating this required great subtlety, utter cynicism, and some imagination, albeit within the confines of class politics. This was the real genius of Nixon and Kissinger. As a real intellectual, the latter always looked back in history to his hero, Prince Metternich of the Holy Alliance, whose diplomatic talents kept the heritage of the French Revolution bottled up for three decades, until 1848, when the prince had to flee for his life. Nixon, for his part, was a ruthless pragmatist whose career originated as a McCarthyite witch-hunter extraordinaire.

Recall that Nixon represented a wing of the U.S. dominant classes that wanted to use nuclear weapons rather than see the Korean War end in a stalemate and also supported their use against China and Vietnam at the time that French imperialism was being forced out of Vietnam in 1954. Recall also that Kissinger publicly supported the use of “tactical” nuclear weapons even in relatively small conflicts. Recall as well that virtually all of U.S. establishment opinion saw “Red China” as the real threat to the capitalist world order, now that Russia had at least agreed to a degree of rapprochement that included nuclear weapons agreements.

Recall in addition that the far left at this time was imbued with support for Maoist China, which could be seen in France 1968, which had a strong Maoist faction in the student leadership, to the U.S., where both SDS and the Black Panthers had embraced Maoism, or countries like India or the Philippines, where Maoist parties were engaged in insurrections. Everywhere, these Maoist tendencies held that China was a truly revolutionary country, as against Russia, which was seen as too complicit with imperialism. The Nixon-Kissinger opening to China was to pull the rug out from under such tendencies, hastening the decline of the global left.

Raya Dunayevskaya on the China opening as global counter-revolution

As soon as news reports appeared indicating that the U.S. and China were reversing over two decades of implacable hostility, Raya Dunayevskaya hit out at this as a betrayal of the global revolutionary movement: “Whether or not what is now mere talk, will, in fact, become the global turning point of ‘the century,’ there is no doubt at all that the alleged super-revolutionary, Mao, has taken the actual super-reactionary Nixon off the hot seat on which he was placed by the Vietnamese most of all, but with them also by the massive US anti-Vietnam war movement as well as the Black Revolution” (Nixon to Peking: ‘journey to peace’ or new alliance for world war?” News & Letters, August-September 1971).

Dunayevskaya added that it had become clear “that Mao-Chou were secretly negotiating with Nixon-Kissinger at the expense of the Vietnamese,” also referring to the “pained outcry of North Vietnam—and the solidarity of the anti-Vietnam war movement the world over with it.”

Looking at these events from an internal, Chinese angle in the same article, Dunayevskaya took up how, after having put down the genuinely revolutionary parts of the Cultural Revolution that had emerged in its wake, like Shen Wu-lien, the regime was now ready to reach a deal with global imperialism: “At one and the same time, the rulers of China put down the “ultra-lefts”, saddled the country with a Constitution in which the military is the decisive force and General Lin Piao is already anointed as the one to rule after Mao’s death. On the international front, the biggest reversal is yet to come as they act out their ‘discovery’ that Nixon is ‘less bad’.”

In “Nixon and Mao Aim to Throttle Social Revolution,” written a few weeks later as the Perspectives Thesis for News and Letters Committees, Dunayevskaya noted Maoism’s global philosophical reach at the time:

The ‘little red book’ may not be quite the fetish the Black Stone of Mecca was, but even as the artificer that Hegel described, Mao knows full well how to mate ‘clearness of expression’ with ‘darkness of thought.’ As disastrous as Mao’s Cultural Revolution ended for the Chinese masses, it continues to exert a pull on the Left abroad. A little Marxism goes a long way, and Mao, the poet, knows well how to dress retrogressionism in revolutionary rhetoric. (“Nixon and Mao Aim to Throttle Social Revolution,” Post-Plenum Bulletin No 1, October 1971, p. 2)

Kissinger and Nixon achieved many of their aims via Mao’s betrayal and their ability to take advantage of the situation. They delayed Vietnam’s victory against U.S. imperialism by four years. They gave Nixon an international triumph that seemed to promise peace and that helped assure his election by a landslide against the antiwar George McGovern in 1972, even though the public had turned decisively against the war by that time. And they undermined the global left with the aid of their new ally.

At a great power level, the U.S. gained China as a powerful quasi-ally in its competition with the other superpower in a state-capitalist world, Brezhnev’s Russia. And China gained a counterweight to Russia, which menaced its northern border. In addition, the U.S. reached new agreements with Russia on better terms now that it was outflanked in Asia.

All this could not prevent Nixon’s downfall in response to his authoritarian power grab in the Watergate affair, in which his opponents also sought to get out of the morass of the war in Vietnam, something Nixon and Kissinger were attempting to continue.

Inside the U.S. Left, the Black Panthers declined in the face of murderous repression from Nixon’s FBI and internal, factional conflict; SDS dissolved into a few small warring Maoist tendencies, none of them with much support; and the antiwar movement continued to weaken even as the war continued. The people of Chile, India, the Philippines, and elsewhere were to feel the brunt of the betrayal, as countless lives were lost. As a Latin American comrade recounted in a conversation as I was finishing this article, “During the Pinochet coup the Chilean leader of a pro-China Marxist party asked help from the embassy of China and was denied entrance. So much for revolutionary solidarity.”

But for Nixon, Kissinger, and Mao, this was a victory.

At the same time, some from the New Left who had been drawn to Maoism learned from these events that they needed to carve out an independent, revolutionary path. In the 1970s, leftwing organizations independent of both Russia and China grew, from India to the U.S., and from Europe to Latin America. This growth included the Marxist-Humanists. And a new generation of intellectuals, most of them to the left of the old Communist and Socialist Parties, engaged in fruitful writings and translations in the Marxian dialectical tradition.

But overall, the 1970s were a period of defeat for the Left, and in this Henry Kissinger’s ruthless but astute policies and actions loom large.