Deciphering China (Part I): Decoupling or New Silk Road?

By Claudio Katz, Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal

Abstract: China’s control of the pandemic has not cancelled out the impact generated by the virus that originated there, as it is closely intertwined with capitalist globalisation. This has made it necessary for the new power to rethink its economic strategy. Its partnership with the United States was shattered by the 2008 crisis but decoupling did not produce the expected results. The proposed New Silk Road presupposes a return to the world market to temper overproduction, but it has rekindled the dispute with Washington. The trade war has already moved on to become a currency war, but it will be settled in the area of technology. No one knows who will win this battle, but political divergences and internal social tensions will define its outcome.

[Note by LINKS: This is the first article in a three-part series by Argentine Marxist Claudio Katz looking at China today and its role in world politics. Although originally published in 2020 (September 18), meaning it is somewhat dated in places, these articles largely maintain their relevance regarding debates on the left over China. Read Part II and Part III. Translation by Federico Fuentes with assistance from Richard Fidler. Original in Spanish here.]

While the pandemic flares up again in the West, China is exhibiting its ability to assert greater control over the virus. Nobody remembers anymore the initial scenes of the outbreak in the East, which Europe and the United States observed from afar. The sequence of infections then deaths became more dramatic as the virus migrated compared to when it first emerged.

China demonstrated a path for containment of COVID, by combining the shutting down of localities with restrictions on movement and social distancing. Western governments that had hoped this would weaken their rival were left disappointed. The pandemic hit their own countries hardest.

All the nonsense spread by Trump about the virus being deliberately fabricated, with the direct complicity of the WHO, to affect the United States can not overshadow the effectiveness demonstrated by China. China’s international image has been strengthened as a result of the respirators and medical equipment it sent to several continents. This “diplomacy of masks” is in line with Beijing’s proposal to transform the vaccine into a global public good.

But it is also true that the pandemic started in China due to the growing prominence of that country in the imbalances generated by globalisation. COVID spread across the planet due to three effects of this process: the worsening of urban overcrowding, the lack of control over global production chains and mismanagement in the industrialisation of foodstuffs. The penetration of capitalism in China has aggravated these impacts.

The Asian giant has already begun an economic recovery that contrasts with the continuing recession in developed economies. But growth rates in the East are well below the usual average. For the first time in decades, the government has not announced a production target and export prospects are as bleak as the level of unemployment (Roberts, 2020a).

This scenario has forced China to review its economic strategy. The same dilemmas that surfaced with the 2008 crisis are coming back to the fore, prompting a discussion over whether the priority should be domestic development or global expansion.

The limits of decoupling

China has achieved exceptional development in recent decades, leaping from a status of underdeveloped to its current position as a power that contends for international leadership. This whirlwind development has no contemporary precedent. In record time, the country became the world’s main workshop and achieved a productive expansion on a scale that recalls the take-off of England, the United States, Germany, Japan or the Soviet Union.

The continuity of this development was severely affected by the 2008 crisis. Exports to the United States hit an insurmountable ceiling. After several decades of close association, the “Chinamerica” link was exhausted. It could not cope with the imbalance generated by Beijing’s trade surplus and monumental debts. The great recession of 2009-2010 put a brake on US acquisitions of Chinese surpluses and the consequent piling up of Treasury Bonds in Asian reserves.

Initially, the two partners tried to continue with the same model, along with some Chinese decoupling from the world market. Beijing resumed its frenetic pace of expansion with large-scale investments in the domestic market and a gradual reduction of its foreign debts.

But this shift to local economic activity failed to reproduce the very high levels of profit generated by the export-oriented scheme. Domestic consumption kept production going, but without generating the level of profits achieved in the world market. Although the feared landing of the Asian economy did not take place, decoupling was halted halfway.

After 2008, China resumed its growth, but without repeating previous records. It doubled the average level of global growth and managed to overtake Japan as the second largest economy in the world (Clegg, 2018). But domestic consumption by high and middle-income sectors was not enough to sustain the same pace of activity.

For this reason, the state’s gigantic plan of public works achieved limited success (Nadal, 2019). The investment rate rose to a peak of 48% (2011), but the production rate declined from 10.6% (2010) to 6.7%-6.9% (2016-2017) (Hart-Landsberg, 2018). The savings rate forged in the heat of the export model placed limits on the opposing scheme of focusing on domestic consumption.

Overinvestment has become the main contradiction of the Chinese economy. It generates surpluses that are unable to find channels for productive use, and stimulates periodic real estate bubbles. The latest construction boom unleashed an indescribable urbanisation fever. Between 2011 and 2013, China broke all world records in the use of cement to build cities that remain empty.

The financial correlate of this productive overcapacity is an enormous volume of credit that has saturated the banking system. The state itself poured sidereal amounts of yuan into the market, which encouraged the bubbles. The flow of local loans — denominated in national currency and divorced from any backing in exports — explosively increased domestic indebtedness (Brenner, 2019).

Only the great control exercised by the state prevented the terrifying capital flight that peripheral countries suffered. But this supervision, in turn, boosted the vicious cycle of over-savings that have no outlet. The government tried, without success, to neutralise the inflationary or recessionary effects of this liquidity surplus through its management of the interest rate and exchange rate.

Several measurements confirm the decline in the level of profits in recent years (Roberts, 2016: 212-214, Hart-Landsberg, 2018). As the attempt to reduce the weight of the export model through boosting its domestic counterpart has failed to achieve the required level of profitability, the Chinese government has embarked on a new external foray.

The New Silk Road

The rise of Xi Jinping to the command of the political regime consecrated this return to the world market. China is no longer trying to take advantage of its cheap wages to produce basic manufactured goods. It is now trying to insert itself into the leading sectors of the global market in order to assert its new profile as a central economy. The New Silk Road [also known as the Belt and Road Initiative] synthesises this objective and is conceived as a channel for unloading surpluses that cannot be absorbed by the domestic market. It also serves as a means to dismantle the financial and real estate bubbles of recent years.

Xi’s economic management underpins these objectives. He has contained indebtedness and deflated stock and real estate prices, while starting to construct the new international trade network. This geographical network is seen as an antidote to overcapacity in production and as a compensator for overaccumulation in finance.

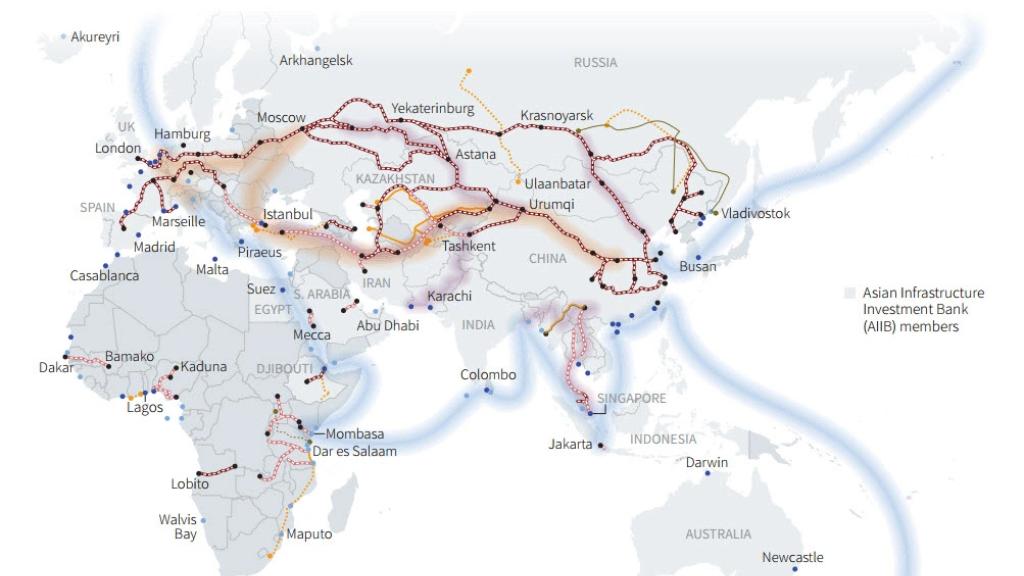

The New Silk Road project goes beyond anything imagined. It will cover 65% of the world’s population by connecting about 100 countries on five continents. It will involve a third of global GDP and mobilise a quarter of the planet’s goods via investments greater than those deployed in post-war European reconstruction (Foncillas, 2019a).

Its construction will connect all the areas required to ensure the placement of Asian exports. The land route will connect China with Europe via continental Asia and the sea route will run through Southeast Asia to Africa and the Maghreb.

Trains from Beijing to Venice and Rotterdam will pass through all the countries of Eastern Europe and be fed by several strategic routes in Central Asia. The aim of this project is to guarantee the foreign investment of surpluses and supply of raw materials, while drastically reducing transportation costs. A commercial project of this scale has never been conceived of before (Rousset, 2018).

The plan was announced in 2015 and reformulated with successive extensions. It is portrayed as a “New Deal on a global scale” because of the centrality of investment in infrastructure, pipelines, roads and airports (Dierckxsens; Formento; Piqueras, 2018). Its dimension is proportional to the size of China’s surpluses.

Overproduction has forced China to resume its search for external markets within a framework of globalisation, which increases the scale of the projects required to retain customers. This principal imbalance of the capitalist economy conditions all the steps taken by Beijing.

New tensions with the United States

The New Silk Road has intensified conflict with Washington and obstructed the friendly response Beijing sought in the face of growing US aggressiveness. The United States is fully aware of the threat posed by China to its waning world domination. That is why it began a multi-pronged campaign to hold back its competitor within the insurmountable barrier of coexistence that global overproduction generates.

Under Obama’s administration, this confrontation unfolded within the framework of globalisation. The two powers fought over partners for their respective free trade agreements. The Asian chapter of the New Silk Road was initially conceived as a response to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) promoted by the United States.

Trump drastically altered the terms of the dispute with his ultimatum of demands. He sought to impose a drastic reduction of the trade deficit on China, through demands for greater purchases and fewer sales. He also sought to recover his country’s declining supremacy, replacing free trade agreements with bilateral negotiations explicitly aimed at favouring US firms. He even sought to discipline all Western partners to follow his command in the battle against China.

But after four years of provocations, he did not achieve any of these objectives. Economic imbalances with Beijing persist and the US establishment is evaluating new ways to confront its challenger. It is not yet clear whether an eventual Biden presidency will mean a return to the Obama model of dispute on the basis of multilateralism and free trade. But in any case the conflict will continue to escalate (Katz, 2020).

China will not be able to escape these tensions if it continues to engage with the same external expansion. The New Silk Road intensifies the discord that Beijing is trying to process through the rules of free trade. Its spokespersons are standard bearers of this banner and praise the globalisation summits in Davos with the same passion that they highlight “comparative advantages” as a rule to regulate trade. They believe that their country has already achieved a level of competitiveness sufficient to rival anyone who plays by the rules of the market.

This strategy represents a challenge to the United States in its own field of capitalist purity. It involves disputes over attracting partners on all continents. The New Silk Road is the new framework for this rivalry. China has set up large banks to offer succulent loans to countries that join the network. Washington, in turn, tries to dissuade all those interested in joining Beijing’s great corridor with the use of a few carrots and lots of sticks.

The immediate battles are being played out in the Asian region. The United States is strengthening alliances with the major players on the Eastern chessboard (Australia, Japan, South Korea and India) to counteract China’s tempting business offers. So far, it has achieved few results.

The same struggle extends to Europe. Although the big players in the region are reluctant to validate the Asian venture, France, Germany and England do not want to lose their slice of big business that they covet.

Trade and currency

Trump favoured trade confrontation with China. He waged a tariff war to penalise his opponent’s imports and facilitate US exports. He used a wide repertoire of threats, ruptures, truces and agreements that led to new rounds of belligerence. The United States eased its trade deficit somewhat without modifying the structural imbalance. And Beijing accepted several minor requests, without accepting any significant demand from its rival (Ríos, 2019).

Given this tariff commotion ended without any definitive result, it is likely that we will see the conflict shift to other terrains. Trade disputes will lead to the recreation of the protectionist blocs of the past, which will affect the very global framework in which many US companies operate.

This contradiction is well known among those at the top of US power, who can see the potential disadvantages of cutting off Chinese supplies to US production. This supply generates enormous profits for the globalised firms of the world’s largest power.

The pandemic has confirmed just how profitable the Asian flow of intermediate inputs is for the health and pharmaceutical sectors. The significant contraction of globalised trade in recent years has not reversed the process of internationalisation of production, nor has it resolved the great dilemma confronting the future of globalisation.

The strategists of both powers know, moreover, that any victory in the trade war will be ephemeral if the winner does not achieve an equivalent triumph in the currency field. The effectiveness of the New Silk Road depends on the gestation of an internationally tradable Chinese currency. In turn, US obstruction of this project is dependent on the permanence of the dollar as the world’s main currency. In the medium term, this dispute will be decisive.

So far, China’s astonishing rise in terms of production and trade has no correlation when it comes to currencies. The dollar reigns supreme in 88% of the world’s transactions, compared to 4% of transactions for the Chinese currency (Norfield, 2020).

This gap bears no relation to the real weight of the two economies. It merely illustrates the continued pre-eminence of the geopolitical-military power of the United States and the financial centrality retained by Wall Street, the Federal Reserve and US banks. The seigniorage of the dollar allows Washington to ignore the limits on emissions of notes that prevail in the rest of the world.

China has sought to erode this pre-eminence, trying different ways to internationalise the yuan as a world currency or at least as the foundation for a collection of different currencies. Both courses require stabilising the yuan at a level that ensures its exchange convertibility. This consolidation requires, in turn, very cautious strategies in the use of devaluation to promote exports.

Beijing is following this path by using its gigantic foreign currency reserves and treasury bonds. But dethroning the dollar is no easy task. Not even China’s productive supremacy at the peak of the world economy will allow it to have any immediate monetary correlative (Roberts, 2020b). For this reason, the new power is building other alternatives in the universe of cryptocurrencies (Petro-Yuan-Gold) or in specific activities (future oil markets denominated in yuan).

An alternative currency to the dollar also requires the consolidation of large stock exchanges. But, so far, the Hong Kong, Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges do not compete with their New York equivalent in terms of capitalisation. That volume indicates the capacity of the listed companies to exert their firepower in capturing firms, acquisitions or loans.

The New Silk Road needs this support, which China is forging through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB). Both entities already have sidereal amounts at their disposal for the great battle ahead in the financial arena.

Technological confrontation

The outcome of the trade or currency war will depend heavily on the outcome of the technological battle. Beijing has launched two strategic plans to fight for supremacy in the sphere of technology. With the “China 2025” project, it has defined ten fields of innovation to reshape its economy. It is attempting a leap from being the world’s workshop to being a supplier of complex goods (Escobar, 2018).

Beijing intends to substantially raise productivity in certain activities (aviation, new energy vehicles, biotechnology), to overcome backwardness (semiconductor industry) and achieve supremacy in decisive segments (robotics, artificial intelligence, bio-medicine, aerospace equipment). With these achievements, it hopes to make the great leap from exporter of basic manufactured goods to epicentre of cutting-edge activities.

This goal requires conquering leadership in the field of 5G, which will define the next directions of the digital revolution. China has embarked on manufacturing and extending the expensive fibre optic network that will enable it to handle the “Internet of Things” designed for the new wave of innovations.

No other country has so many companies and technicians dedicated to the development of this variety of artificial intelligence. It has made rapid progress in the construction of a new generation of telescopes, computers and satellites. It is also a driving force in e-commerce, which it began developing later than its rivals (Foncillas, 2019b).

China has been able to create a group of firms that already compete with the five US giants (Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Google). Huawei competes in high technology; Alibaba in Internet clouds; Xiamoi in the creation of software; and Geely in the construction of electric cars. The most critical area for the country is imported processors and memory chips, but from 2011 to 2016 it tripled production of these integrated circuits (Salama, 2018).

To curb this sweeping advance, the United States has focused its confrontation with China in the field of technology (Noyola Rodríguez, 2017). Trump’s trade demands are concentrated in this area, raising countless accusations of theft and digital piracy. Those allegations have as much validity as his ramblings about a virus created by a rival to contaminate the West with a pandemic.

The occupant of the White House focused his last barrage of tariffs on imports connected to technological activity. But he is not acting alone, nor does he only express the interests of US sectors reluctant to go along with the appeasement suggested by his globalist adversaries. The technological battle with the East is a banner of the entire ruling class, which understands the decisive character of this battle.

China’s dizzying development seriously threatens US digital supremacy and all Washington elites agree on the need to open fire before it is too late. They have more offensive tools at their disposal in the technological field than in the area of trade.

The US onslaught began with vetoes on Chinese participation in space missions and re-imposing the bans of the previous decade on the installation of IBM computers in Asia. It seeks to perpetuate the dominance of US firms in the global sales of networks, consolidating the digital monopoly that currently prevails in the standards, formats, languages and codes for this grid.

The central battle is over command of 5G technology and consequent control of the huge flow of data required to monitor smart cars or homes. Two Chinese companies (Huawei and ZTE) and three companies associated with US patronage (Samsung, Nokia and Ericsson) are engaged in a struggle over this development. Trump has already resorted to all imaginable outrages to sabotage Huawei’s offers of competitively-priced facilities.

His onslaught included a judicial provocation to imprison company executives and several demands to break international agreements signed with the company. But the tycoon has so far failed to obtain the desired results. Some governments accepted his ultimatum (Australia, New Zealand), others are hesitating (Canada, England) and several have preferred to continue with Beijing’s business proposal (Saudi Arabia) (Feás, 2019).

The United States focuses its offensive on China’s insufficient access to semiconductors. Trump has revived all the ghosts of the Cold War to block Eastern acquisition of these chips. He is betting on obstructing the assimilation of the know-how needed by his rival to position itself on the front line of the digital frontier.

Beijing already suffers from this handicap in several sectors. German and Japanese suppliers have retained, for example, the know-how for the large wind turbines and high-speed train projects they have installed in China. The United States is trying to increase barriers to technology transfer, but the battle has just begun and no one knows what the outcome will be.

Uncertain outcome

Determining who will win the China-US economic confrontation is a favourite puzzle of the mainstream media. There are favourable forecasts for both sides and rigorous tracking of who takes the lead in each camp.

The number of companies that both contenders have in the ranking of the world’s top 500 firms is a closely watched indicator for assessing the battle. The impressive change registered in this table would seem to remove any doubt about the potential winner.

In 2005, the United States had 176 of the top companies while China only had 16. In 2014, the former dropped to 128 and the latter rose to 95. Four years later, the Asian giant jumped to 108 companies and has now displaced its rival with 119 companies against 99.

These figures confirm which economy is in the ascendency, but it does not shed light on the strength of each side. With 20% fewer firms, US companies have a greater combined income and surpass their adversaries in the main parameters of capitalist “efficiency” (Mercatante, 2020). The amounts of foreign direct investment they receive (or the inverse placement of sums abroad) corroborate these differences.

The same scenario can be seen in technology. China is advancing faster, but the United States maintains a significant advantage in key areas. It invests a relatively larger portion of its GDP in research and development, maintains a stable share of the generation of patents and appropriates the bulk of the profits generated by innovation. In addition, it persists as the largest producer of intensive services and concentrates a high proportion of cutting-edge activities (Roberts, 2018). In the global high-tech ranking, it has 22 of the top 50 companies and outstrips the rest in innovation expenditures.

Eastern firms, moreover, exhibit greater difficulty in designing complex applications or commanding digitised sectors (Salama, 2018). For that reason, China’s responses to Trump’s provocations have been very cautious. Its enemy is very resourceful and can inflict severe damage to its breakneck development.

Those predicting a Chinese triumph are projecting the advantages of recent decades onto the coming years. The new power already has four banks of global impact and ten companies in the cream of the crop of best businesses. Not only does it lead in terms of low and medium complexity manufacturing, but it has also increased its high-tech production threefold. It is also true that it came out of the 2008 crisis with flying colours and forged a network of international alliances (Shanghai Cooperation, BRICS) that allowed it to embark on the New Silk Road (Merino, 2020).

But it is worth remembering that the official discourse of the Soviet Union was based on a very similar thesis of irresistible rise, based on successive competitive victories. It foresaw an unstoppable victory for the “socialist camp” over its decadent enemy. This view not only ignored its own imbalances, but also underestimated the capacity of reaction of the dominant imperialism. The United States brought the USSR to its knees and blocked the international economic ambitions of its two great competitors (Japan and Germany).

This does not disprove the current scenario of a clear US setback in the face of China’s dizzying expansion. This disparity is the main fact of the past decades and continues to express itself through strong tendencies. But it is a mistake to extrapolate what has happened to date into the future, ignoring the significant distances that still separate the largest power from the second power. US imperialism’s own publicists are interested in presenting a false image of US weakness. They tend to exaggerate the power of their enemies to raise fears of imaginary external aggressions within the Western population.

China has grown at a spectacular rate, but it is not the engine of the global economy. It has ample margin to continue its internal expansion, overcoming the hindrances of underdevelopment through non-capitalist paths. It has a long way to go to achieve the level of development already achieved by the great powers of the West. It does not need to get involved in the competitive race that prevails in global capitalism.

Testing the new situation

The New Silk Road concentrates the tensions that lie ahead. The project has taken its first steps but faces significant financial hurdles. The new rail network would greatly speed up transportation, but it is less profitable than maritime routes and relies on state subsidies. Current high-speed trains do not operate at a profit and expansion is highly risky. This imbalance in gigantic investments caused major projects (such as the Panama Canal) to falter in the past, before they were converted into strategic routes.

Another critical flank is the participation of the numerous national recipients of Chinese loans. The repayment of these sums must be justified by public works in line with the needs of each country. Chinese interest in each port, road or railway station does not necessarily converge with the priorities of its Asian or European partners. These setbacks may affect the final design of the route.

But those problems are secondary to the threat created by the eventual stagnation of the world economy. A global trade mega-project can only prosper in a framework of growing productive expansion. Occasional financial tremors and periodic recessions would not inhibit the venture, but a long period of low growth would undermine its effectiveness.

The project emerged against a backdrop of increasing trade, over and above production. This feature of the globalisation boom has changed in recent years. Trade no longer exceeds the level of productive activity. The New Silk Road presupposes that the trade boom will re-emerge, which is why it is promoted with the optimistic credo of free trade.

But it is unknown how the project will be reformulated in a scenario of low growth (Borella, 2019). The crisis inaugurated by the pandemic makes it necessary to reconsider the plan, in the face of the frightening economic figures of the first half of 2020. The collapse of GDP has surpassed the collapse suffered in the equivalent junctures of 1872, 1930 and 2008-2009, and the recovery of Asian economies has not yet extended to Europe or the United States (Ugarteche; Zabaleta, 2020). Will the New Silk Road be viable in this context?

Domestic political unknowns

The dilemmas facing China are not only economic or geopolitical. Internal political outcomes are equally decisive. In this field, a large ignorance of the Asian reality predominates in the West. While no characterisation of the United States would omit the decisive impact of the electoral confrontation between Trump and Biden, the future of China is evaluated without taking into account the basic facts of its local life.

This blindspot is not only due to a language or cultural gap. Liberal prejudices have generalised the myth of uniformity, obedience or absence of divergence in Chinese society. It is simply imagined that a vacuum resulting from authoritarianism prevails (Prashad, 2020).

With this biased view, the Chinese political system is questioned while ignoring what has happened in its counterpart. They tend to forget the non-existence of genuine democracy in the plutocracies of the West. This blindness to their own reality prevents them from perceiving the variety of tendencies and opinions present in other political regimes.

In fact, the clashes between different currents in the Chinese leadership have been a determining factor in the direction the country is taking. There are multiple sides in dispute and a serious counterposition exists between pro- and anti-globalisation sectors. Both groups have been baptised with different names that highlight their geographic location (the coast versus the interior) or their stance on privatisation (liberal versus illiberal). Also important are their positions on the extension of the principle of profit (mercantilists versus reformers) and towards the priority assigned to external and local expansion (globalists versus market-internationalists) (Petras, 2016).

Tensions between both sectors have determined the courses of greater integration into the world economy or significant internal withdrawal. Among those who follow these clashes, there is general agreement that Xi Jinping plays the role of arbiter. This leader ensures the necessary balances that have made viable the unified command in place since 2012 (Rousset, 2016).

The current president has exercised his authority by introducing limits on the various clashing positions. He contained the turn towards new privatisations promoted by the neoliberals and stopped the rethinking on external expansion advocated by the opposite wing. Xi Jinping also consolidated his leadership through a campaign against the corruption of a large segment of high officials who enriched themselves from speculative bubbles.

Since his arrival at the helm of the country, he has implemented a strong purge to restore the deteriorated political legitimacy of the national and regional leaderships of the Communist Party. He especially targeted the large network of bribes that flourished in moments of exponential growth and profit fever.

Xi Jinping has tried to restore the credibility of the dominant political organisation. He has limited the influence of the segment managing foreign investment (“comprador elite”) and of the elite of godchildren of the old Communist leadership (“princelings”) (Mobo, 2019). He also prevented a revision of the current course sponsored by radical sectors, but reintroduced the reading of Marxism and gave certain recognition to the Maoist legacy. His reorganisation illustrates the extent to which it is indispensable to evaluate the domestic political scenario in order to characterise the course that China will follow.

Social protest

Dissatisfaction with inequality is also a determining factor in the direction taken by the country. In China, inequality has emerged as a shocking novelty, together with the spectacular rise in the number of multimillionaires. The wealthy are catered for in luxury shops and are distinguished by their yacht clubs.

The irruption of this wealthy sector is not synonymous with simple social polarisation. Its appearance has converged with a great expansion of the middle class, an enormous increase in consumption and the tripling of formal salaries. But inequality is evident when looking at the harsh living conditions faced by agricultural workers and those on the lowest rungs of the urban labour ladder.

These gaps generate protests, which leaders register with great attention. China is no exception to this conditioning factor in the political life of any nation. The impressive social weight of the proletariat makes it necessary to seriously consider the mood of the people. It should be remembered that the mass of wage earners in the country comprises a quarter of the world’s working class.

The reorganisation of old industry has, since the 1990s, led to the relocation of millions of workers to new activities and to an important loss of social conquests. The subsequent huge influx of rural migrants has further weakened these gains (Hernández, 2016a).

However, a new generation of workers has established its own spheres of protest, with demands for wages and improved working conditions. These demands have found an echo in society and in the leadership itself. The success of certain strikes has determined the cautious response and inclination to concession that prevails in the political leadership (Hernández, 2016b). An emblematic protest in July 2018 further illustrated, moreover, how the demand to create new unions has led to a renewal of the worker-student alliance and a greater hearing for the left (Qian, 2019).

Popular demands constitute a central element of the path that the country will follow. But China raises questions that go far beyond these characterisations: Is its economic model based on liberal or illiberal principles? Is the prevailing system socialist or capitalist? The second article in this series will answer these questions.

References

Borella, Guillermo (2019). “La otra hegemonía global. China aspira al liderazgo tecnológico”, 24-3, "https://www.lanacion.com.ar/opinion

Brenner, Robert (2019). “China’s Credit Conundrum” Interview with Victor Shih” New Left Review 115 March-April https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii115/articles/victor-shih-china-s-credit-conundrum

Clegg, Jenny (2018). “The Decade of a Rising China: 10 Years After the Financial Crisis” August 31, https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/08/31/the-decade-of-a-rising-china-10-years-after-the-financial-crisis/

Dierckxsens, Wim; Formento, Walter; Piqueras, Andrés (2018). “La salida del capitalismo al fallar el intento de salir de la crisis capitalista” 20/06.

Escobar, Pepe (2018). “Tariffs ‘kick off 50-year trade war’ with China”, July 6. https://asiatimes.com/2018/07/tariffs-kick-off-50-year-trade-war-with-china/

Feás, Enrique (2019). “La guerra del 5G y sus lecciones para Europa”, 1-5 http://blognewdeal.com/

Foncillas, Adrián (2019a). “La ambiciosa nueva Ruta de la Seda china llega a Europa y se enfrenta a nuevos desafíos”, 2-3, https://www.lanacion.com.ar

Foncillas, Adrián (2019b). “El paso de fábrica global a gran potencia en innovación”, 24-3, https://www.lanacion.com.ar

Hart-Landsberg, Martin (2018). “A Critical Look at China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative” October 2. https://economicfront.wordpress.com/2018/10/02/a-critical-look-at-chinas-one-belt-one-road-initiative/

Hernández, Mario (2016a). “China y América Latina: ¿Una nueva matriz para una vieja dependencia?” In ¿A dónde va China?, Editorial Metrópolis, Buenos Aires.

Hernández, Mario (2016b). “La situación de la clase obrera en China” In ¿A dónde va China?, Editorial Metrópolis, Buenos Aires.

Katz Claudio (2020). “El ‘resurgimiento americano’ que no logró Trump”, 28-7, www.lahaine.org/katz

Mercatante, Esteban (2020). “China en el desorden mundial”, 26-7, www.laizquierdadiario.com/

Merino, Gabriel E (2020). “China y el nuevo momento geopolítico mundial. Boletín del Grupo de Trabajo China y el mapa del poder mundial”, CLACSO, n 1, mayo

Mobo, Gao (2019). “China puede ser todavía alternativa al capitalismo”. 10/10/ https://www.sinpermiso.info/textos/china-puede-ser-todavia-alternativa-al-capitalismo-entrevista

Nadal, Alejandro (2019). “China y la guerra comercial: una perspectiva amplia”, 17 jul. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2019/07/17/opinion/025a1eco

Norfield, Tony (2020). “China y el poder de EE. UU”, 26-7 www.laizquierdadiario.com

Noyola Rodríguez, Ulises (2017). “China desafía la guerra comercial de Trump”, 25 sept. http://www.iade.org.ar

Petras, James (2016) “China: Reformistas y Mercantilistas” In ¿A dónde va China?, Editorial Metrópolis, Buenos Aires

Prashad, Vijay (2020). “Entrevista sobre el socialismo chino y el internacionalismo hoy”, 21-5 https://observatoriodetrabajadores.wordpress.com/2020/05/25/

Qian, Ben-li (2019). “Jasic Struggle: Debate Among Chinese Maoists” May-June https://againstthecurrent.org/atc200/chinese-maoists-debate/

Ríos, Xulio (2019). “Guerra comercial EEUU-China, ¿acuerdo o tregua?” 27-12 https://rebelion.org

Roberts Michael (2016), The long depression, Haymarket Books, 2016.

Roberts, Michael (2018). “Trump, trade and the tech war”, 02/04 https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2018/04/04/trump-trade-and-the-tech-war/

Roberts Michael (2020a). “China in the post-pandemic 2020s”, 22/05 https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/05/22/china-in-the-post-pandemic-2020s/

Roberts, Michael (2020b), “Capital Wars” 19/07 https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/07/19/capital-wars/

Rousset, Pierre (2016). “Xi Jinping, ¿un nuevo Mao? Sobre el Sexto Pleno del Comité Central del Partido Comunista de China en la dinámica”, noviembre 23 https://vientosur.info/xi-jinping-un-nuevo-mao/

Rousset, Pierre (2018). “Geopolítica china: continuidades, inflexiones, incertidumbres”, 25/07, https://vientosur.info/spip.php?article14038

Salama, Pierre (2018). “Nuevas tecnologías: ¿Bipolarización de empleos e ingresos del trabajo?” Problemas del Desarrollo, vol 49, n 195, México.

Ugarteche Oscar; Zabaleta, Jorge (2020) “Cómo va la pandemia en la economía mundial: Primer semestre del 2020” 21/08 https://www.alainet.org