The rise and fall (and rise and fall) of the Egyptian Left — Part 2

First published at Left Berlin.

Phil Butland and Helena Zohdi interview Hossam el-Hamalawy about the history of the Egyptian Left. You can read Part 1 of the interview here.

Hi, Hossam. We finished our last installment by focusing on the events of 1961 when the Egyptian Left was in a bad state. Did things get any better afterward?

The third communist wave started in 1968, a year after the war with Israel. Usually in leftwing literature, whenever events that took place during the year 1968 are mentioned, the focus is usually on the West. Quite legitimately, people have focused on important events such as the uprisings in May 1968 in France, or the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, anti-Vietnam War protests, the martyrdom of Che Guevara, or the student occupations that were taking place across Europe.

But the Arab world also had its own 1968. It was not separate, and events were partially inspired by what was happening around the globe. I wrote my master’s thesis on this period, and it’s available online.

The year 1968 was marked by student dissent across Egypt. In February 1968, there were serious student protests taking place for the first time since 1954. Students took to the streets. The trigger for these actions was the sentencing of Air Force generals during mock trials. After the disaster of the Six-Day War, Nasser had to have a scapegoat. The generals were to blame, and they deserved to be prosecuted – but they nonetheless were given light sentences.

The protests were started by Helwan factory workers, and during the events, police opened fire on the workers. The workers also sent delegations to university campuses, in particular the Ain Shams University in Cairo. This was the first time there was a joint students’ and workers’ focus within the Egyptian Left.

Nasser realized he needed to retreat and offer the movement some concessions. He presented what was called the 30 March program, one month after the protests. In this, he acknowledged that there were problems with the country’s socialist project, and that there should be more room for self-criticism. Nasser also presented some democratic reforms.

Simultaneously, the so-called War of Attrition began. This conflict started in 1968 and ended in 1970. During this time, as part of anti-occupation operations, Egypt launched commando raids into Sinai while Israeli forces retaliated, often by bombing civilian targets.

There were several horrible massacres, including when a primary school was bombed in Egypt’s northern Sharqia province. This is an event that Egyptians remember still today. We also commemorate the bombing of oil refineries in Suez.

The state had to move residents of the Suez Canal cities to Cairo and elsewhere to protect them. These cities turned into ghost towns. I grew up in Nasr City, an eastern suburb of Cairo. We had a district which was known as the “Suez people” area, to which some displaced people were moved.

At the same time, Egypt’s social movements continued to grow. And a tiny minority of Communists who had refused the dissolution of the party in 1965 began to build bridges with newly radicalized students. More Communist organizations started to develop.

One of the most important groups was at the time was the Egyptian Communist Party – 8th of January. The party’s name refers to the events of 8 January 1958, when 40 Communist factions came together and formed the Egyptian Communist Party.

Another organization which was also important in the 1970s was the Egyptian Workers’ Communist Party. They critiqued Nasser and the Egyptian Stalinists, but they were coming more from a Maoist perspective, Maoism generally being a more radical version of Stalinism.

There is one thing about 1968 that we haven’t talked about, when Russian troops went into Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring. Suddenly, Stalinism didn’t seem as radical as it used to be. Amid Western student movements, at least, one witnessed the rising influence of both Trotskyism and Maoism. Was something similar happening in Egypt?

Not with regards to Trotskyism. Historically, the Trotskyists were always a tiny minority, on the fringes of the movements. In the 1940s, there was a small Trotskyist group called Art and Freedom, which later changed its name to Bread and Freedom, and was mainly composed of surrealist artists. Later in the 1970s, another small Trotskyist group formed called the League of Communist Revolutionaries, a small Fourth International Trotskyist group.

Separately, from the stories that I’ve read about Tony Cliff, who was later a leading Trotskyist in the United Kingdom, when he was trying to flee Palestine, he was initially thinking of coming to Egypt as he had always regarded Egypt as the center of the Arab working class. When he realized the situation of the Trotskyists in Egypt, however, he said he’d be better off someplace else.

The Maoist situation was different. In Egypt, relations between Nasser and China were excellent. There wasn’t any censorship on Chinese literature. My father, for example, could get hold of Mao’s writings in Arabic from the Chinese cultural center.

Around the world at this time people were talking about China’s Cultural Revolution, seen positively as a student rebellion against bureaucracy. No one really knew about the massacres or the power struggles, in which Mao cynically used student mobilizations to destroy his enemies.

So, for many leftists of this generation, China represented the answer. In addition, part of the Maoist package was armed struggle. At the time, the models of success and inspiration included Cuba, Che Guevara, the Palestinian struggle, and Vietnam.

After Nasser died in 1970, the student movement was revived in 1971. Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, promised the liberation of Sinai, yet nothing happened. Tahrir Square in Cairo was famously occupied in 1972. Students were saying: “Look at the Vietnamese, they are confronting the Americans, we need a people’s war.” The ideas of Maoism at the time struck a chord with the newly radicalized students.

Left-leaning students’ societies on university campuses led the movement, calling themselves the Society of the Supporters of the Palestinian Revolution. This was telling about who has historically been a source of inspiration for Egyptian dissidents. The Palestinian cause has always been important for Egyptian activism.

And then there was another war with Israel.

In 1973 war broke out, and Sadat quickly proclaimed victory. But the Egyptian national question, which was perceived to be solved, only added fuel to the social question. The student movement however temporarily lost steam as for three years, all mobilization addressed the war with Israel to liberate Sinai.

Then in 1974, the social questions were relit with the government’s so-called open-door policy. Sadat and Chile’s Augusto Pinochet were the two pioneers of neoliberalism in the Global South. Sadat began neoliberal reforms with the help of the United States in 1974, and also entered into peace talks with the Israelis.

In the same year, there was a revival of industrial action with an important strike at the steel mills in Helwan, south of Cairo. In 1975, there was a strike at Mahalla, which was a hotbed for industrial militancy in the textile mills. According to reports, Sadat sent in helicopters at low altitudes to terrorize the striking workers. The revolts were put down by force.

In 1976, a huge strike by public transport workers brought Cairo to a standstill. These are the highlights, but basically, strikes were erupting everywhere during these years.

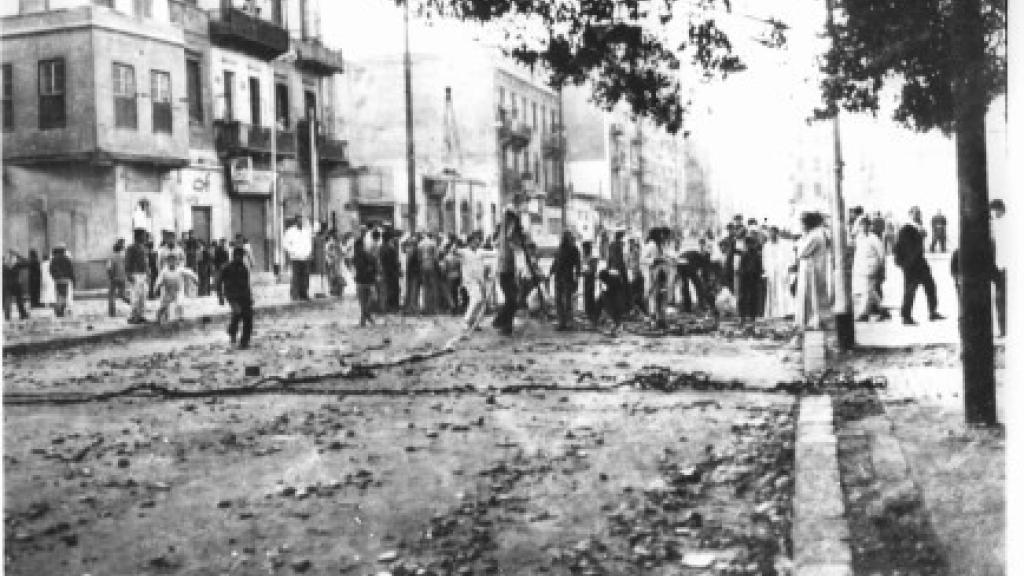

All of this culminated in the January 1977 bread riots. For two days, Egyptians participated in a national strike, triggered by Sadat’s neoliberal strategy to remove subsidies from basic commodities, including bread. Bread is a very important daily food staple for Egyptians, and the Arabic word for “bread” is also a synonym for “living.”

The uprising ended after two days, for two reasons. First, Sadat sent in the army after local police forces proved themselves ineffective. Secondly, Sadat also performed a U-turn and retracted all his “reforms.” Following these riots, the regime didn’t have the courage to implement its neoliberal reforms until the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s. This is how shocking the uprising was for the regime.

But the failure of the Left to lead this uprising into a full-fledged revolution also signaled the beginning of the end for the Left. Already in the early 1970s, Sadat maintained an unofficial alliance with Islamists. He released their leaders from prison. And the regime’s security services gave them more room to operate, to act as a counterweight to the Left. This was a tactic, by the way, that has been used in several other countries in the region.

As we now know, the Islamists became a Frankenstein’s monster, created by Sadat. Their development followed two trends. One was a reformist route, represented by the Muslim Brotherhood. The other was more radical, represented by Islamic Jihad and Gama’a Islamiyya. The latter two briefly united in 1979, and then split again after the assassination of Sadat.

Discussions among more radical members took place while they were in prison, about why an Islamic revolution hadn’t yet happened. The plan was to kill the president, and the masses would rise up. But after Sadat’s assassination, mainly nothing happened.

There is a brilliant book in Arabic by Hisham Mubarak. You may have heard the name, for example, from the Hisham Mubarak Law Centre. Mubarak is a former Communist who passed away in the 1990s. He was also briefly a member of the Egyptian Revolutionary Socialists.

Hisham Mubarak wrote a book called, “The Terrorists Are Coming,” in which he brilliantly explains the fights between Islamic Jihad and Gama’a Islamiyya inside prison, including over theological issues. But he explains how these issues were not actually theological, as they more reflected organizational and political matters.

This was the beginning of the end of the Egyptian Left, the failure of the revolutionary uprising following the end of the Sadat regime. And by the 1980s, the Left was more or less declared clinically dead. And once the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Left was officially dead, marking the end of Egypt’s third communist wave.