Lessons of Russia's October 1917 revolution (Part II) — What kind of revolutionary organisation?

Read Part I “Coup or mass insurrection?” here.

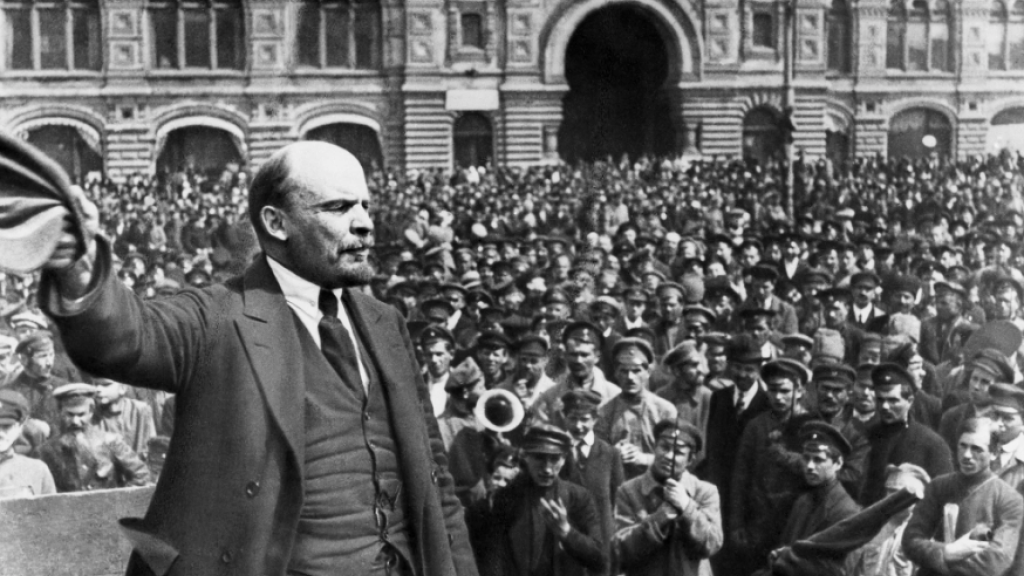

The Bolsheviks are often discussed as a “party of a new type”, with Vladimir Lenin at its head as the key theoriser of its practice as a “vanguard”. There is much in this argument, but only if it is accompanied by an understanding that, in this regard, Lenin was not the innovator.

When Lenin became politically active, in the 1890s, he adopted the aim of the Russian Marxists that the country’s workers should lead a popular movement to overthrow the tsar and institute political freedom, which would prepare the ground for workers’ power to bring about socialism. Then, with the 1905 revolution, Lenin argued that the weakness of liberalism in Russia was shown. Meanwhile, the worker movement should not “stop half-way” in leading the democratic revolution but complete it, so that it could more easily and in accordance with its strength, begin the task of socialist revolution: “We stand for uninterrupted revolution”.1

Researcher Lars Lih has explained that this concept of the “hegemonic” role for the working class in relation to other classes in the struggle was combined with a perspective for “the merger of socialism and the worker movement”. Lenin observed this merger occurring very broadly, but especially important to him was the experience of the German Social Democrats (SPD), the most advanced example of building a revolutionary party in the late 19th century. According to Lih:

The SPD was a vanguard party, first because it defined its own mission as “filling up” the proletariat with the awareness and skills needed to fulfil its own world-historical mission, and second because the SPD developed an innovative panopoly of methods for spreading enlightenment and “combination”.2

The SPD was confident it could actively transform “the worker movement by expanding awareness”. To achieve this, it set out to expose and counter all examples of oppression. In 1902, in What Is to Be Done?, Lenin wrote: “The German party particularly strengthens its position and widens its influence precisely because of the unremitting energy of its campaign of political indictments.” Its methods included: an apparatus of agitators, starting with its parliamentarians; party publications (first of all newspapers, the most important popular media at the time, but also pamphlets, leaflets, and so on); workers’ institutions — unions, educational associations and clubs of all sorts — that the party was to ensure worked toward raising proletarian awareness; and, ultimately, “a truly nation-wide party”, working well beyond the existing scope of the party’s effective influence. “We should dream!” Lenin wrote, of:

A weekly newspaper, regularly distributed in tens of thousands of copies throughout Russia. This newspaper would be a small part of a huge bellows that blows up each flame of class struggle and popular indignation into a common fire.3

What would the merger of socialism and the worker movement consist of at the beginning of the 20th century? In Germany, which had been experiencing relative economic expansion and political stability, the worker movement — its unions, its votes, its culture and its thinking — already operated almost without exception within the framework of the SPD, independently and against recognised society. In Russia, the tsarist regime was in crisis. It faced unrest among students and many others over its autocratic rule, a rising strike wave and military defeat in the Russo-Japanese war was soon to come. Insurrection was in prospect. Some in the revolutionary movement believed that systematic organisation of the kind Lenin advocated — engaged in frequent, regular, politically far-reaching work throughout the country through agitation centred on a common newspaper, avoiding the tsarist police as best it could by being underground — would mean being “involved in something that cuts them off from the crowd” and being swept aside by that crowd in its upsurge. Lenin responded that the party would be more likely to “take their place in front, at the head of crowd” with this level of organisation because the party’s members would be:

involved exclusively in all-sided and all-embracing political agitation, that is, precisely work that brings closer and merges into one the crowd with its stikhiinyi [elemental4 ] destructive force and the organisation of revolutionaries with its purposive destructive force.5

For the next decade and a half, the Bolsheviks, in various guises, pursued the objective that the workers' movement should come to merge with socialism. Lenin exuded confidence in the upsurges of the movement and castigated those who thought it could not be part of the struggle for socialism. In Lih's words, workers needed and would heed the socialist message. What he criticised was party work that was ineffective or needlessly limited in getting that message out, because he considered that had failed to provide to the worker movement its maximum scope for development.

In the 1905 Revolution in Russia, many tens of thousands of people joined the various Russian-language factions and national sections of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), which showed a mass socialist party could be formed under the tsarist state. In the following years, when the regime reasserted its rule and, for the most part, its repression, the illegal party was re-formed. Other RSDLP members urged that the party scrap underground work and instead establish a labour congress that would operate within the boundaries tsarist laws imposed. By the time the Russian workers' movement re-emerged in protest and strikes in 1912, it supported the illegal party over “liquidation”: from among the politically-aligned media, workers largely choose to read and fund the Bolsheviks’ publications; in the 1912 voting for the semi-parliamentary Duma, the workers’ curia (voting was in class-based electorates) only elected candidates from the underground party; and many union leaderships were aligned with the underground.

Until Lenin’s last writings, he continued to make these same arguments. In 1920, in Left-Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder, he tried to explain what in the Russian experience spoke to those who were forming the new Communist parties throughout the world about how they could, beyond saying revolutionary phrases, become effective revolutionary actors. According to him, that experience showed certain conditions were needed for success. He talked in terms such as maintaining, testing and reinforcing the disciplined action of the party; we might say to stop it going off the rails and, thus, heading in the right direction. Only “prolonged effort and hard-won experience” could create such conditions. “Correct revolutionary theory” can certainly ease this, but it cannot be “a dogma[: it] assumes final shape only in close connection with the practical activity of a truly mass and truly revolutionary movement”. A party’s political leadership, and strategy and tactics, are only proven to be correct when “the broad masses have seen, from their own experience, that they are correct”. Meanwhile, the party must be able “to link up, maintain the closest contact, and — if you wish — merge, in certain measure with the broadest masses of the working people — primarily with the proletariat, but also with the non-proletarian masses of working people”. And, yes, the party had to have “class-consciousness … devotion to the revolution … tenacity, self-sacrifice and heroism”.6 Perspectives for a merger of socialism and the worker movement and for a vanguard party are in fact combined.

Lih points out that if “the emancipation of the working classes must be the work of the working classes themselves”, then the proletariat must go through some preparatory process to achieve that.7 Left-Wing Communism tried to win anarchistic leftists (the Council Communists and other “left” Communists, and Wobblies, members of the Industrial Workers of the World) to “the party principle”. That principle’s rationale is told in the narrative of the merger of socialism and the worker movement.

In 1917, the Bolsheviks went from a party persecuted for its anti-war stance, with its principal leaders exiled to Siberia, Switzerland and the United States, to achieving its aims of a merger of socialism and the worker movement and a hegemonic role for the working class within a revolutionary movement. After February, some members left to join groups, chiefly the “minority” Menshevik faction of the RSDLP, which supported the new regime. During the year, however, the Bolsheviks grew, expanding in numbers at least tenfold, but also through realignments in which the Mezhraiontsy group, which included Leon Trotsky, and a left Menshevik group joined the Bolsheviks.

The Bolsheviks also, at times, argued.

In April, they debated what they would do in the aftermath of the Tsar’s overthrow and the formation of, first, the Soviets and, then, the Provisional Government. The result has frequently been discussed as a “re-arming” of the Bolsheviks, in which Lenin’s presentation of the April Theses on his return to Russia moved the Bolsheviks to a stance of opposition to the Provisional Government. The key focus for that discussion has been the Bolsheviks’ adoption of the slogan, “All power to the Soviets”, under which they set out to help convince workers, soldiers and peasants, who were represented in the Soviets, to support this change in sovereign political power.

Lenin’s April Theses, however, also proposed, among other things, to re-name the Bolshevik organisation as the Communist Party. Many Bolshevik activists gave what Lih calls “practical considerations” to not move on this. He cites Mikhail Kalinin: “Social-Democrat” was not “so befouled” among the Bolsheviks in Russia, Kalinin stated, as it was for the returning emigres.8 Practical concerns are not irrelevant to choosing a party’s name (“brand”, if you like): indeed, when the Bolsheviks took the name Communist in 1918, they kept Bolshevik in brackets after that to still identify with their heritage. But in March and April of 1917, the Bolsheviks were also seriously discussing unification with the Mensheviks to pursue a struggle with liberalism. For example, Stalin, who on his return from exile in Siberia had taken on co-editing Pravda, urged this, while Yakov Sverdlov, another Central Committee member who at the end of April became that body’s first Secretary, was opposed.

The Bolsheviks’ April debates confirmed Bolshevik-Menshevik disunity within the RSDLP, but could not fully sunder the links and pressures exerted between the two organisations (for example, the October 10 Bolshevik Central Committee meeting which decided they would prepare for insurrection meet at the home of the Bolshevik Galina Flakserman, who had dissuaded her husband, the Menshevik diarist Sukhanov, from returning home). Until the July Days, the Bolsheviks allowed that if the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries would take power through the Soviets, the Bolsheviks would become a loyal opposition, a Soviet minority trying to become a Soviet majority.

Even on the day the October Revolution took power, the Bolsheviks backed a proposal for a Soviet government involving all other Soviet parties, although this was not carried out because the now-minority “defencists” would only agree to this if they dominated the government. Also, some Bolsheviks did not seem to have thought an insurrection could succeed without Menshevik support. Stalin, who supported preparations for insurrection, but sympathised with their Bolshevik opponents, said “our whole situation is self-contradictory”.

The Bolsheviks in fact discussed when and how to prepare for mass insurrection throughout September and October. In the aftermath of the Kornilov revolt, as soon as support began to swing towards the Bolsheviks in the Soviets and the “defencists” had refused to compromise with them to form a new government, Lenin wrote insistently and broadly, from hiding, that the time was ripe to prepare for insurrection. No other members of the Bolshevik Central Committee appear to have immediately agreed with him; that body did not support Lenin’s view until early October. Even in the days before the October Revolution, some of them still said insurrectionary preparations would disorganise the revolutionary forces, in public as well as among the party ranks. Chief among these were Lev Kamenev, who had been the most prominent Bolshevik in Russia before February, and Grigory Zinoviev, who had been Lenin’s principal colleague in exile.

These debates were felt as sharp differences. A Petrograd enthusiast for the April Theses said these “exploded like a bomb” among the Bolsheviks.9 The debate on insurrectionary preparations was also fractious. First Lenin and later Kamenev proposed to resign from the Central Committee (Lenin’s offer was not accepted, while Kamenev’s was, but this was not effected), Lenin demanded the expulsion of Kamenev and Zinoviev from the Bolsheviks, and the Central Committee at one point proposed to exclude them from representing the party. Yet the Bolshevik leadership maintained a relative cohesion. Kamenev and Zinoviev, for example, were continually put in leading roles by the Bolsheviks, even after they had argued publicly against the Central Committee’s decision to prepare for insurrection.

Lih has suggested the aims all Bolsheviks held help to explain this overall cohesion. He has amassed evidence that shows, according to Lih, that “the open call for full soviet power” Lenin initiated in April was an uncontroversial “shift in tactics” for the Bolsheviks, who sought proletarian hegemony in the democratic revolution. Lih’s thesis of continuity in the thinking of Lenin and the Bolsheviks might again be supported by similar research on the October Revolution, about which Lih’s view is that the Bolsheviks emphasised class power and that they understood their role as socialists taking part in a democratic revolution.

Lih, however, puts down the unresolved party name discussion to being about Lenin’s “personal enthusiasms”, which other Bolsheviks saw as neither part of their core consensus nor contradicting it, and thus “allowed to drift into the fine print of the Bolshevik message”.10 To my mind, the Bolsheviks’ differences, and how they were experienced, is better explained in terms of Lih’s broader argument that Lenin, self-consciously, upheld orthodox Marxism, but he was open and willing to apply that according to new circumstances as he understood these – with regard to his argument with other Bolsheviks, more quickly and readily than them. When Lenin discussed how to build a revolutionary party, he would typically argue that his views represented the existing Marxist perspective, which others were seeking to revise. In the years between 1914 and the revolution, this meant that Lenin maintained, in Lih’s words, an “aggressive unoriginality” in which past suggestions about what might need to be done about turn-of-the-century revisionism now became essential tasks.

First, he concluded, from the failure of most Social-Democratic parties to pursue the anti-war activity that the Second International had decided upon with the prospect of world war in mind, that any opportunist trend, pursuing immediate interests for some workers against the historic interests of the class, must be excluded from the revolutionary party. Otherwise, the party would be prevented from using capitalist crises to work to overturn capitalism. He wrote that “the old theory that opportunism is a ‘legitimate shade’ in a single party that knows no ‘extremes’ has now turned into … a tremendous hindrance to the working-class movement”.11

Second, he considered the problem historically: opportunism, previously understood to be a “mood”, had become a trend within these parties over a period of decades (as discussed above, but for other reasons, the Bolsheviks had already excluded any significant opportunist trend). Finally, he asked and answered “the fundamental question of modern socialism”:

Is there any connection between imperialism [that is, the current monopoly stage of capitalism, which emerged at the end of the 19th century] and the monstrous and disgusting victory opportunism … has gained over the labour movement in Europe? … [while capitalism lives at the expense of all workers,] imperialism somewhat changes the situation. A privileged upper stratum of the proletariat in the imperialist countries lives partly at the expense of the rest of the oppressed … the desertion of a stratum of the labour aristocracy [these relatively privileged workers] to the bourgeosie has matured and become an accomplished fact … Now, a ‘bourgeois labour party’ is inevitable and typical in all imperialist countries.12

Lenin’s arguments about the relationships between imperialism, the formation of the labour aristocracy and the inevitability of bourgeois labour parties, the historical emergence of opportunism as a definite trend in workers’ politics, and the exclusion of opportunism from the revolutionary party were new considerations for “the essence of Marxist tactics”. Yet he did not propose some new type of party, because the narrative of the merger of socialism and the workers' movement, and confidence that workers will take part in this, remained. Only where that worker movement will be found and how the merger will be achieved had changed:

Neither we nor anyone else can calculate precisely what portion of the proletariat is following and will follow the social-chauvinists and opportunists. This will be revealed only by the struggle, it will be definitely decided only by the socialist revolution. But we know for certain that the ‘defenders of the fatherland’ in the imperialist war represent only a minority. And it is therefore our duty, if we wish to remain socialists, to go down lower and deeper, to the real masses: this is the whole meaning and the whole purport of the struggle against opportunism…

The only Marxist line in the world labour movement is to explain to the masses the inevitability and necessity of breaking with opportunism …13

Trotsky’s History points out that Lenin’s quarrel when he arrived in Russia with “Old Bolshevism” about the completion of the democratic revolution turned on this, not on what the February Revolution had achieved:

Lenin saw, of course, as clearly as his opponents that the democratic revolution was not finished … only the rulership of a new class could carry it through to the end, and that … could be achieved no otherwise but by drawing the masses out from under the influence of the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries – that is to say, from the indirect influence of the liberal bourgeoisie … Lenin, therefore, demanded an irreconcilable opposition to all shades of social patriotism. Separate the party from the backward masses, in order afterwards to free those masses from their backwardness. ‘We must abandon the old Bolshevism,’ he kept repeating, ‘We must make a sharp division between the line [emphasis added] of the petty bourgeoisie and the wage worker’.14

The Mensheviks were supporting the liberals, as were the Social Revolutionaries. None of the Bolsheviks accepted this. The main thing for them was that the political unity of workers and peasants should be in those classes’ own interests in order to serve a socialist political future. Holding this perspective is what had made them Bolsheviks, but Bolsheviks also thought about other things, and not least among these was how to secure the new power, which is why they had differences.

The whole situation, however, was not contradictory as Stalin has said. True, the old Bolshevik aim of overthrowing the Provisional Government and the old Bolshevik desire for cooperation with the Mensheviks, who refused to cooperate for that aim, were irreconciliable. Historically, other things came into play. The most important of these was a merger of socialism and the worker movement in Russia in 1917, which created the politically independent working class, led by the Bolsheviks, that made the October Revolution.

- 1//www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/sep/05e.htm

- 2What Is to Be Done? In Context, Haymarket Books

- 3What Is to Be Done? In Context, Haymarket Books

- 4Lih has left untranslated the Russian word stikhiinyi. This he explained was because stikhiinyi’s readily translates in English into “elemental”, but this is a word for which in English other forms of it are not then available to use. Other translations of What Is to Be Done? have, as it turns out, translated stikhiinyi in this particular passage as elemental, but elsewhere these translations have used spontaneous, spontaneity and so on. This has, in turn, led to a confusion that Lenin criticised spontaneity, where in fact he was hoping only to ensure the masses’ action was purposive. Otherwise, it is hard to understand how he could celebrate revolutions as “festivals of the oppressed”.

- 5What Is to Be Done? In Context, Haymarket Books

- 6//www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/

- 7What Is to Be Done? In Context, Haymarket Books

- 8What Is to Be Done? In Context, Haymarket Books

- 9www.links.org.au/lars-t-lih-all-power-soviets-biography-slogan

- 10What Is to Be Done? In Context, Haymarket Books

- 11www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1915/csi/

- 12www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/oct/x01.htm

- 13www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/oct/x01.htm

- 14Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, Haymarket Books