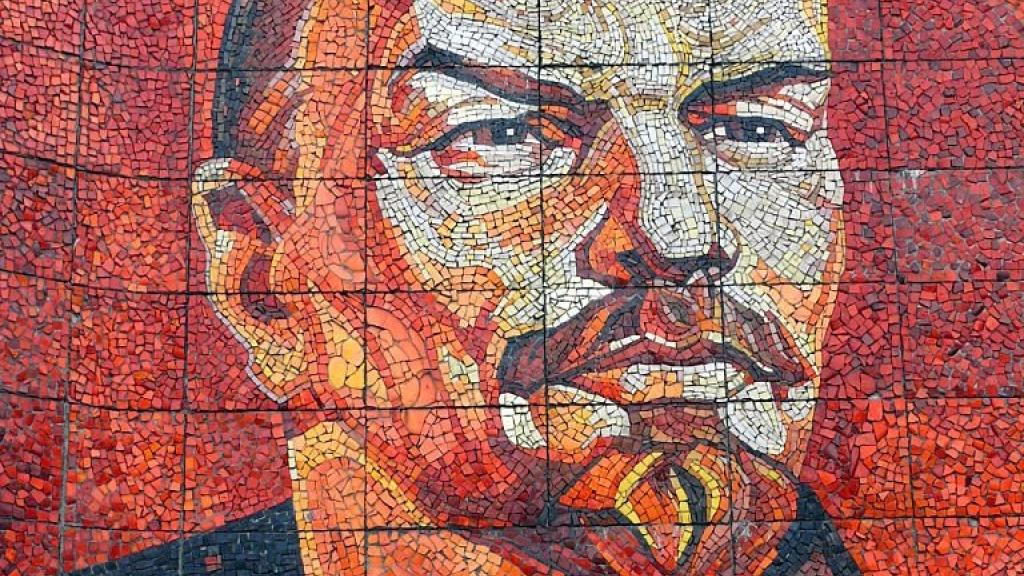

Paul Le Blanc: What would Lenin do today?

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov — known by his revolutionary alias, Lenin — was a central figure in the history of the twentieth century. He was a leader of the 1917 Russian Revolution and a founder of the modern Communist movement, who was perceived by millions of people either as Evil Incarnate or a Benevolent Genius. I would argue that he should be seen as a human being who can be shown to have made more than one serious mistake. But as Lenin himself noted, “he who never does anything never makes mistakes,” and Lenin did quite a lot. His development of Marxism’s revolutionary cutting edge has relevance for the future. I want to focus on some ways revolutionary activists can make use of his ideas today. The great African American poet, Langston Hughes, expressed his global impact in these lines:

Lenin walks around the world.

Black, brown, and white receive him.

Language is no barrier.

The strangest tongues believe him.

If we do it right, we can draw useful notions from what this comrade has to offer, as we face such realities as anti-racist upsurges, the multi-faceted escalation of feminist struggles, the immense challenges of climate change, wars in Gaza and Ukraine and elsewhere. In the United States, we have also been faced with the interrelated phenomena of mild socialist Bernie Sanders and super-capitalist Donald Trump. Rightward veering “Trumpism” poses an especially ominous threat — one that dovetails with the ascent of right-wing authoritarians around the world, such as Javier Milei in Argentina, until recently Jair Bolsanaro in Brazil, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Narendra Modi in India, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey. I will focus on the US electoral realities later in this presentation, because I am most familiar with them.

In the face of all this, what would Lenin do? To deal with this question adequately, I think it will help to broaden it. Is it possible for us to make use of Lenin’s ideas 100 years after his death, and if so — how? Another way of posing this question would be: “What would Lenin’s approach be to using Lenin’s basic orientation 100 years after his death?”

All the specifics of Lenin’s analyses cannot not simply be assumed to be applicable in the very different context of our time. At the heart of Lenin’s political approach is the notion that while the use of Marxist theory is essential for building revolutionary movements and struggles, it must be used not as a dogma, but as a guide to action. Related to this is the dialectical notion that “nothing is constant but change.” Essential to Lenin’s dialectics is also a recognition that continuities are blended intimately into the changes.

Another essential element in Lenin’s orientation involved the non-dogmatic utilization of historical materialism, which helps us see three realities: (1) economic development is central to the development of history; (2) the incredibly dynamic capitalist system is the dominant form of economy in modern times; and (3) class divisions are decisive, and under capitalism a small minority of capitalists secure immense wealth and power by exploiting the labor of, and squeezing wealth out of, the lives and labors of the great majority of people who make up the working class.

Despite multiple changes — for example, in the size and nature of the working class (which is bigger and more occupationally diverse than it used to be) and the structures and technologies associated with today’s capitalist system as a whole — the underlying dynamics of capitalism remain similar from Lenin’s time to ours. The three points I identified as part of historical materialism manifest themselves differently than was the case 100 years ago, but nonetheless they continue to operate and shape the reality of our own world.

Two essential elements were constant in Lenin’s approach. One was not to settle for simplistic and comforting dogmas, but instead to approach everything with a critical mind, to base one’s understanding on what he called “stubborn facts,” seeking real information with a drive to keep learning and learning and learning about the complexities of reality. A second essential element involved a refusal to settle for Marxist analysis as simply a passive contemplation of what and how things are. Lenin refused to detach social, economic and political analysis from an activist engagement, from the restless and insistent question: what is to be done?

For Lenin — from the time he became a young Marxist activist to the end of his life — this added up to an insistence that we must not bow to the oppressive and exploitative powers-that-be, and that we must never submit to the transitory “realism” of mainstream politics. Instead, all political action should be measured by how it helps build working-class consciousness, the mass workers’ movement, and the revolutionary organization necessary to overturn capitalism and lead to a socialist future.

At this point we must emphasize something that should be obvious, but which many would-be Leninists lose sight of. In Lenin’s time, throughout the capitalist world there were powerful and influential socialist workers’ movements — influenced by revolutionary Marxist ideas — that were more or less predominant among millions of working-class people, in their workplaces and communities and political life. Developments of the twentieth century — often insidious, often horrifically violent — have undermined this reality and pounded it to rubble. Mass workers’ consciousness and movements and influential revolutionary organizations have persisted only as faded fragments where once they were powerful. For those remaining committed to Lenin’s basic approach, this lends an urgency to the notion that all political action should be measured by how it helps rebuild what has largely been lost.

To what extent is it still useful or relevant to retain Lenin’s (and Karl Marx’s and Rosa Luxemburg’s) old focus on the working class? I continue to be influenced by the kinds of points CLR James made in the early 1960s, when this question arose within his own organization in the US. James explained the context in terms that seem incredibly similar to what we face now. He said: “Large sections of the American population are horrified and revolted at the rapid degeneration of American society.” He continued: “The sense of crisis is national, and has attained such a scope that one cannot see how the American bourgeoisie will be able to handle it.” It seems to me James’s next point has greater resonance than ever: “Whatever form a solution or the beginning of an attempt at solution will take, it seems fairly obvious that for the first time the American working class will have to assume, will be forced to assume national responsibility, think its own independent thoughts, carry out its own independent actions.” James concluded: “It is to me certain that if the American working class should find itself, not necessarily at the very start, but rapidly enough, forced to intervene independently in the task of national regeneration, that one of the first things it will do is to reorganize the process of production. If it will act at all – and either it will act or the degeneration of American society (and world society) will continue.

Some of James’s comrades split from him on this, moving in the direction of what later assumed the label of “identity politics.” Shifting class to the margins of their analyses, they gave pride of place to such identities as race, gender, and age. Over the past few decades, the counterposition of “class” versus “identity” has absorbed much energy and attention. But I am influenced by the blending of the two by my mentor George Breitman, a seasoned working-class intellectual, who wrote at the end of the 1960s:

“The radicalization of the worker can begin off the job as well as on. It can begin from the fact that the worker is a woman as well as a man; that the worker is Black or Chicano or a member of some other oppressed minority as well as white; that the worker is a father or mother whose son can be drafted [into the military]; that the worker is young as well as middle-aged or about to retire. If we grasp the fact that the working class is stratified and divided in many ways — the capitalists prefer it that way — then we will be better able to understand how the radicalization will develop among workers and how to intervene more effectively. Those who haven’t already learned important lessons from the radicalization of oppressed minorities, youth and women had better hurry up and learn them, because most of the people involved in these radicalizations are workers or come from working-class families.”

If all this is true, then Lenin’s basic political orientation continues to have relevance — which means political action should be measured by how it helps rebuild mass working-class consciousness and movements, as well as effective revolutionary organizations. This brings us back to the question of “what would Lenin do” in relation to developments and struggles of our time. I will focus on US realities, with which I am most familiar. Other parts of the world face their own specific realities, which overlap with what I will touch on here.

Some questions are less complex than others. Surely it is crucial to support anti-racist struggles against police violence associated with the slogan “Black Lives Matter,” as well as an end to the US-funded slaughter by the state of Israel of thousands of men, women, and children in Gaza. As masses of people are mobilized around such perspectives and find that their mass pressure can force decision-makers to grant reforms, saving and improving lives, the result can be radicalizing in ways that advance the consciousness and self-confidence of significant components of the working class. There are, of course, super-militant activists who scoff at reform because revolution is needed, insisting on more radical demands that are understood only by the most radical of activists. The result is revolutionaries’ self-isolation in much smaller and less unified protests. More than once, such super-militant activists criticized Lenin as being far too tame and lame to embrace their self-isolating demands and tactics.

This kind of division flared among Lenin’s Bolsheviks after 1906, leading to a sharp and acrimonious split in 1909. Some preferred urban guerrilla warfare and revolutionary consciousness-raising among socialist activists, as opposed to the mass electoral and reform activity championed by Lenin. But here, as always, Lenin’s measure of what made sense was not adopting the most “revolutionary” stance. Instead, the measure was what would actually help generate working-class consciousness, expand the mass workers’ movement, and enhance the experience and influence of the revolutionary organization. The organization of the super-militant Bolsheviks soon disintegrated, while the Leninist-Bolsheviks became a hegemonic force in the Russian workers’ movement.

In the same period, Lenin carried on a relentless struggle against a component of the Menshevik faction tagged “the Liquidators.” These comrades wanted to focus on organizing for reforms by restricting themselves to legal activities allowed by the Tsarist autocracy. They were abandoning the original program of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party of overthrowing Tsarism through a democratic revolution. Lenin was in favor of fighting for reforms — but not through abandoning revolutionary commitments. This would not advance mass working-class consciousness and movements, nor would it help build an effective revolutionary organization.

How does this apply to political developments and realities in the United States? In 2016, Bernie Sanders campaigned as an open socialist to be the Democratic Party’s nominee for President. He directly challenged corporate capitalist control of the Democratic Party, calling for far-reaching social and economic reforms beneficial to the working-class majority. Millions of people, including substantial layers of the working class, responded positively. Hundreds of thousands of young activists flocked to support the Sanders campaign, a large percentage of which swelled the membership of Democratic Socialists of America from several hundred to almost 100,000. A growing number of activists went on to run as open socialists on the Democratic Party ticket — some getting a significant percentage of the vote, and even being elected. The idea of socialism, defined variously but positively by millions of people, became part of the political mainstream. This was repeated in the Sanders Presidential campaign of 2020.

Sanders was denounced by some who saw themselves as far more revolutionary. These super-militant activists (plus super-militants who were not very active, except on the internet) made rejection of Sanders into a measuring rod to separate those who were presumably true socialists and those who were phonies. It was evident that Sanders was not a revolutionary socialist. He pointed to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s liberal-capitalist New Deal of the 1930s as an example of socialism.

Another problem was that there was no way to ensure accountability of most socialist candidates running as Democrats to any socialist program or constituency. More than this, the Democratic Party really was (as Nancy Pelosi and other party leaders emphasized more than once) a capitalist party that would not tolerate efforts to turn it into a socialist party.

A challenging “socialist moment” truly existed in the Democratic Party, but its shelf-life was clearly quite limited. Either Sanders and others would be driven out of the party, or they would end up capitulating — remaining loyal to and doing the bidding of the pro-capitalist leadership of the Democratic Party. For key travelers on this socialist road through the Democratic Party, it is this second option that has been chosen. Even if Lenin found himself on this particular road, he would certainly now be urgently posing the question: what is to be done?

This brings us to the question of Trump, who is far from a typical conservative or reactionary Republican. He is a crook, a liar, a bigot, a bully, a self-promoting huckster, and an irresponsible authoritarian who is quite happy to encourage the growth of, and to mobilize for his own purposes, large-scale fascist movements that are crystallizing in the US. Given the current balance of forces, both in 2020 and 2024, there may be only one possibility of actually stopping him: electing his Democratic Party rival, Kamala Harris.

What would Lenin do? It seems to me he would continue to be guided by what guided him in the past: helping build the working-class consciousness, the mass workers’ movement, and the revolutionary organization that will be necessary to overturn capitalism and lead to a socialist future. I envision Lenin emphasizing four points:

Point 1. Tell the truth. Both Trump and Harris favor the interests of the rich over the rest of us. They are our enemies, not our friends. To campaign for either means telling lies — something we must not do.

Point 2. At the same time, face the truth. Any left-wing political parties running candidates in this election are not serious alternatives in the 2024 elections. Despite their truly admirable intentions, they have no chance of winning or of advancing the interests of the working class.

Point 3. One may choose to consider pulling the lever for Harris in order to register most effectively popular opposition to the figure who presents a qualitatively greater evil: Trump – but the Harrises themselves are part of the problem, not part of the solution. Trump has gained credibility because of the inevitable failures of political figures such as Joe Biden and Harris.

Point 4. It makes sense to concentrate time, energy, resources on two things: (a) working hard to advance real non-electoral struggles through which we can build victories and consciousness; (b) in tandem with such struggles, carrying out socialist education and agitation (focusing on the mess we are in, how we got into this mess, and the pathway to get out: which means building independent social struggles and movements, plus creating our own working-class political party).

We must recognize that our own daunting task of recreating a global mass socialist movement will have to occur in an era of catastrophe — the destabilization and unraveling of the global environment and a consequent wave of economic calamities and mass fatalities. In this we are cursed by good fortune turning to bad fortune.

Fortunately, a scientific consensus projects that climate change might still be halted, preventing our planet from being overwhelmed by cascading catastrophes. This will require dramatic, decisive immediate action on a global scale. Unfortunately, the necessary changes will be too costly, in the short run, for the businesses and governments that make the decisions. So far, the necessary changes are not being implemented.

Liberal politicians offer reassuring rhetoric, phony compromises, and inadequate policies. Fake populists on the extreme right deny the realities of climate change altogether, resorting to authoritarian, bigoted, and violent policies in response to ominous problems threatening our world. As increasing millions of the world’s people are impacted by the cascading catastrophes, a mass disillusionment with the capitalist status quo is likely, with a deepening radicalization.

In contrast to Lenin’s time, we lack mass labor and socialist movements in most countries where they existed in the early 20th century. We must create the mass movements we need — more or less from scratch. But how?

I want to focus here on what strikes me as one key element. Some analysts have urged what they call a Green New Deal. (Some use different labels: a strategy for climate jobs or climate justice.) Social critic Naomi Klein says: “In tackling the climate crisis, we can create hundreds of millions of good jobs around the world, invest in the most systematically excluded communities and nations, guarantee health care and childcare, and much more.” She adds: “The result of these transformations would be economies built both to protect and regenerate the planet’s life support systems and to respect and sustain the people who depend on them.” This transitional approach combines multiple goals: people before profit, decent homes, good communities for all, health care for all, education for all, mass transit and communication systems for all, nourishing food, access to cultural and recreational nourishment, creative outlets, genuine liberty and real justice for all.

To the extent that we can build such struggles and such a movement — while expanding a deepening consciousness within the working class based on such experience — we are creating conditions out of which it will become increasingly possible to build the kind of mass socialist workers’ movement that we need. We can be open to building organizational coalitions and even class alliances around specific demands, but our struggle requires an elemental political independence from — not reliance upon — capitalist politicians. Our struggle must be based on the elemental needs of the working class, which are in collision with the drift and dynamics of capitalist profit-making. The logic of our struggle goes in the direction of increasing democratic, working-class control over economic policies and developments. To the extent that there is success in such efforts, combined with an understanding — a consciousness — of the meaning of (and need for) such struggles and victories, a force for an actual socialist revolution can be advanced.

While I am convinced that struggles around climate change must increasingly become central to revolutionary socialist efforts in countries throughout the world, it is also absolutely true that there are a number of other struggles — some existing now, and some that will flare up in the future — on which socialist activists will be compelled to focus attention and energy. In all cases, however, I think they will be well advised to utilize the Leninist approach outlined here.

Stemming from today’s conditions and from the consciousness of expanding layers of youth and the experiences of the laboring majority, it may be possible to build a fundamental challenge to the existing system of power, and create a better world. As we strive to advance that process, there is much to learn from the ideas, insights, and experiences of freedom fighters who went before. Lenin — with all of his accomplishments and insights, all of his mistakes and heroic efforts — is among the freedom fighters we should look to.

This is based on recent online talks to socialist gatherings in Dublin, Boston, Istanbul, and on July 12 at London’s Arise Festival’s current series on Lenin.