Late Marx on colonialism, gender and indigenous communism: An interview with Kevin Anderson

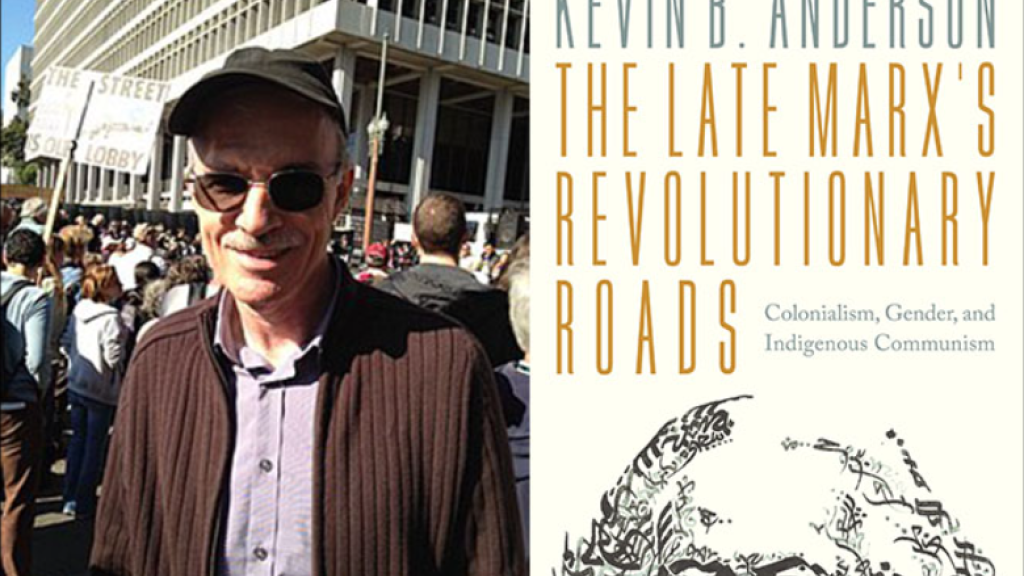

In this latest book, The Late Marx’s Revolutionary Roads: Colonialism, Gender, and Indigenous Communism, Marxist sociologist Kevin B Anderson delves into Karl Marx’s final writings — some of which have only recently come to light — to unearth key ideas of critical importance for socialists today.

Anderson is a Professor of Sociology, Political Science and Feminist studies at University of California, Santa Barbara and the author and editor of various works, including his groundbreaking Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies and, more recently, A Political Sociology of Twenty-First Century Revolutions and Resistances.

Federico Fuentes sat down with Anderson to talk about his new book for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

Your new book focuses on Marx’s later writings. Why the specific interest in late Marx? Are you seeking to contrast it with an “early Marx”?

Similar to those decades ago on the “early Marx,” discussions of the “late Marx” have been going on for some time, though they have only really crystallised in the past five years. My book, Marx at the Margins, came out about 15 years ago and looked at some of Marx’s later writings that were available at the time. But in the past five years, we have had Kohei Saito’s, Karl Marx's Ecosocialism: Capital, Nature, and the Unfinished Critique of Political Economy, and Marcello Musto’s, The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography, among various others.

In my opinion, we cannot reject the late Marx any more than the early Marx: both are Marx and both say a lot of interesting things. Also, I do not think we can point to some kind of break between the “mature” Marx of Capital and Grundrisse and either of these periods. What I wanted to do with this book was to specify the late Marx as a distinct period in his writings.

In your introduction, you note some Marxist scholars have narrowly focused on Marx’s writing regarding “capital and class to the exclusion of other issues”? What are these other issues you seek to bring attention to in your book?

While several others have done work on the late Marx’s ideas regarding ecology, I have focused my attention on his notes regarding race, gender and colonialism. These issues are present throughout Marx’s writings, including in his earliest stages. But some aspects become more pronounced over time, both quantitatively and in terms of new positions he adopted. That is what I seek to draw out.

Why are these issues important for our understanding of Marx’s critique of capitalism?

If you look at the penultimate chapter of Capital Volume I, Marx talks about the forces of production becoming more and more concentrated, which in turn leads to growth and concentration of the working class as a social force. Marx outlines how capital develops over time, explaining that the time for revolutionary transition will come and that capital will have to be overthrown to overcome capitalism’s contradictions.

But there is no mention of race, gender or the state. What Marx presents is an abstract model — abstract in a good sense, because he is trying to focus on the most salient characteristics of capitalism. But it means his explanation of capitalism in Capital Volume I remains at a very general level, one that can be applied to almost any industrial capitalist society.

Yet when you drill down and compare capitalism in England in 1870 to, say, capitalism in the United States now, you can immediately see that it is more complex. And Marx delved into these complexities throughout his life, even in his early years.

Marx, for example, viewed the US and Brazil, which were the only two large capitalist countries with modern slave-based production, as forms of racialised capitalism. In the 1850s, he wrote that perhaps the revolution would start not in the most industrially advanced countries, but in the periphery, namely China and India. When an uprising occurred in Poland in 1863, Marx wrote to Friedrich Engels that “one may hope that this time the lava will flow from east to west.” But these ideas were never very elaborated at the time.

It was towards the end of his life that Marx started focusing a lot more on these issues. For example, Marx looked at interactions between colonised sectors and the so-called core capitalist countries, such as between Ireland and England. But he also looked at the relationship between the English and Irish inside England, which he viewed as similar in some ways to the racialised relationship between white and Black workers in the US.

That is very interesting because the two are both directly connected to colonialism: on one hand, you have the Irish colonial factor and national movement (which he supports), and its impacts on British capitalism. On the other, you have this proletariat of Irish immigrants inside England who have been forced to migrate, largely due to British colonialism. So, he is looking at this issue from various angles.

Unfortunately, some Marxists today consider such complexities and issues particular to different capitalist societies as extraneous, when in fact they are very important.

Did his evolving views affect the way he envisioned revolutions?

Marx’s abstract model led him to initially believe that England, given its large industries and proletariat, was the only country with the economic conditions for an anti-capitalist revolution.

But by the late 1860s, his thinking started to change. Marx still viewed British workers as having a lot of revolutionary potential, but he started to see that the revolutionary energy might come from outside the most advanced industrial sectors of the English working class. Marx instead started to see that an agrarian uprising in Ireland could be the spark to shake up Britain and push it in a revolutionary direction.

Something else emerges in Marx’s writings in the late 1870s and early ’80s. He starts to see these revolts in the periphery not only as politically important for chipping away at the strength of core capitalist countries, but also as containing communist possibilities. He really zeroes in on Russia, which he starts to view as the new centre of revolutionary energy on the continent.

In his last writing — the 1882 preface to The Communist Manifesto — Marx asks the question: “Can the Russian obshchina [peasant commune], though greatly undermined, yet a form of primeval common ownership of land, pass directly to the higher form of Communist common ownership?” His response is that “if the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting point for a communist development.”

This represents a huge reversal from the language of the Communist Manifesto in 1848. Back then, Marx argued that old agrarian relations had to be uprooted and destroyed. That is why he supported free trade; he wanted capitalism to spread everywhere and shake up the old pre-capitalist structures. Now Marx was saying that elements within these pre-capitalist social structures — so-called primitive communism — could be the basis of a revolutionary movement.

What can you tell us about how Marx viewed gender and capitalism in his later writings?

Marx looks at gender quite extensively towards the end of his life. Engels’ book, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State — which is in some ways a great book — was largely based on notes Marx took during the last three years of his life. But the issue of gender was one of the most difficult parts of my book.

One of the difficulties was that while Marx’s writings on indigenous societies (mainly in the Americas) and on Ancient Greece and Rome are full of discussion on gender, this issue is not directly connected to revolutionary movements and challenges to the system. His writings on Ireland in the late 1860s or on Russia in the 1870s talk a lot about revolution, but make no specific mention of gender. It is only really at the very end of his life, in 1881, that he goes back, for example, and looks at gender in Ireland pre-British colonisation.

His writings seem to go a bit against what Engels wrote later, however. Engels said that because patriarchy and gender relations were tied to private property and the state, that by targeting those one would be targeting patriarchy and gender relations. This view led Engels to write, adapting a phrase from Hegel: “The overthrow of mother-right was the world historical defeat of the female sex.”

However, when Marx looked at gender relations among the Greeks and Romans, he did not view it as one of unbroken domination. Marx pointed out that in some ways Roman women had more freedom than Athenian women. This seems to indicate that he saw ups and downs in gender relations, rather than an undifferentiated world historical defeat, as expressed by Engels.

If you think about an unbroken world-historical defeat of women, two problems emerge. First, this tends to deny the agency of women over the millennia, as Marx notes in Rome or could be mentioned in many other contexts.

Second, if this defeat, consolidating patriarchy, occurred more or less simultaneously with the rise of private property and the state, then under modern capitalism we can attack patriarchy most effectively by targeting capitalist private property as the economic foundation of both patriarchy and the state. It followed that women’s movements should be auxiliaries of the socialist left, not autonomous and free-standing. That, in fact, was the policy of socialists in the generation after Marx and Engels.

How did all these evolving views affect Marx’s revolutionary activities?

Let’s take Ireland: Marx and Engels, while always supporting Ireland versus Britain, were initially very hostile to bourgeois Irish nationalists, who they viewed as not caring about the working class. But by 1869-70, you had a progressive nationalist movement in Ireland, the Fenian Brotherhood, which was a plebeian movement just as interested in lowering rents as in kicking out the foreign occupier. It was not a socialist movement, but a class conscious one. Nevertheless, Marx came to salute the Fenian Brotherhood and their agrarian program.

Marx also concluded that hard work was needed to gain the trust of Irish workers in England, especially as the people he worked with in the local section of the International Workingmen's Association were largely English. He said they needed to let Irish workers know they supported Irish self-determination, and even independence if that is what they wanted, to break down the wall of distrust, split those workers away from the bourgeois nationalists and recruit them to the International.

In Russia, the situation was quite different. There was no nationalist movement there, certainly none that was left-wing. Instead, you had all kinds of different socialists. Most were intellectuals who loved Capital and wanted to apply it very dogmatically to Russia. They talked about the need to drive peasants off the land in order to industrialise Russia and create a proletariat. Marx told them this was not what he had meant. But you also had another wing, the populists, who lacked theoretical clarity but whom Marx admired as they too saw certain revolutionary potential in Russia’s peasantry.

Of course, we do not know what Marx would have done with any of the writings at the end of his life. But we do have the preface to the Communist Manifesto, where he talks about the need to unite these elements — Russian agrarian communism and the modern Western European socialist proletariat. For Marx, the two had to find ways to unite.

Do you believe Marx’s later writings challenge certain prevailing ideas among Marxists today?

I think the notion of progress gets challenged quite a bit by Marx’s later writings. In his earlier writings, Marx views the shift from feudalism to capitalism as more straightforward progress. But over time, the cost of this progress appears more and more in his writings.

By Capital Vol I, Marx is writing that capitalism “turns every economic progress into a social calamity,” especially for the working class. He still views capitalism overall as progress — he never gave up that view completely — but in his later writings he is saying things he would not have said before on the negative aspects of progress.

The other side of the coin is that he starts to see potential building blocks for socialism in some pre-capitalist collectivist social structures. Ironically, if you said that in a meeting of Marxists in Russia in 1900, you would be called a populist, not a Marxist.

Some people said Marx made an exception for Russia due to its different development path. But you can see in his writings on India and Indigenous societies in North Africa and Latin America, that Marx also believed communal social structures in those societies could be a basis for revolution. That is a shift from his writings in the 1840s and ‘50s, where Marx was aware of these communal structures, but saw them as the basis of oriental despotism and closed off to any form of progress.

What implications do you see in these writings for the left today in terms of revolutionary subjectivity?

Today, there are dozens of different viewpoints within the global left. But if we look at those with large levels of support, we can point to slightly more reformist forces such as those around [US democratic socialists] Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, [La France Insoumise leader] Jean-Luc Mélenchon and [former British Labour leader] Jeremy Corbyn.

They tend to focus on class, capital, economic inequality, the plight of the working class and the need for left-of-centre parties to connect more with the trade union movement. Some will explicitly say that we need to get away from issues of identity, such as race, gender and sexuality; that the left talks too much about them and this turns off the white working class, or do not target capital enough.

Then you have the left that emerged from the Black Lives Matter and Palestine solidarity movement, as well as much of the student left, who tend to prioritise identity and view white workers as conservative simply because they are white and privileged — even if often the people saying this are way more privileged.

Marx was clearly aware of race, gender and colonialism, but it is not enough to just say how good it is that he was more up-to-date than we thought. For Marx, these issues were always connected to capital and class — that is what is so often lacking today.

Marx’s writings can help us realise that we need to merge these two lefts. I do not mean in a populist, uncritical way, but neither side can simply dismiss the other as there is much radical energy in both. We have to find ways to have real dialogue and unity.

The Palestine movement today offers us an opportunity for this, because both lefts are very much onboard with this movement. The chance is there to have some kind of dialogue. The potential was seen in [Democratic Socialist of America candidate] Zohran Mamdani’s stunning electoral victory in New York, a rare bright spot in a country under the growing threat of Trumpist fascism.

France is another example where, on one hand, you have a gigantic labour movement, as seen with the mass strikes in 2023 and, on the other, regular explosions of anger inside the banlieues [poor suburbs] against police brutality that same year. Yet the two have had very little connection to each other.

What Marx was saying in his Ireland writings is that we have to find ways to connect the workers: movement with the banlieue uprising, because these often semi-unemployed youth of colour are among the most oppressed of the population. Unfortunately, trade unions have not done this, though Mélenchon’s group really did try to involve these sectors in the socialist left, which is important.

And to the extent that this ties into the issue of colonialism in Marx’s writings, these are just as, or even more important today when looking at how different local struggles have impacted on and sparked so many others around the world. A great example is how the 2011 Arab uprisings sparked many protest movements, starting with Occupy Wall Street in the US that same year.

Whether we are talking about colonised or semi-colonised peoples, or peoples from the periphery, we are dealing with people whose living and working conditions are worse, and levels of exploitation higher, than workers in core capitalist countries. It is among them that so many of the current uprisings are coming from. I think today there is more of a sense that these struggles can have an impact across different geographical, cultural and linguistic divides.