Would Marx approve this year’s Nobel?

Innovation won the Economic Nobel this year. Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt were honored for a simple engine: invention plus incentives plus diffusion equals growth. Karl Marx would not quarrel with the mechanism; he would go straight for power. Who controls the complements that make innovation productive and who pockets the gains? Why are so many countries unable to leverage innovation to spur their growth and converge with the most developed economies?

The global record answers badly. China is the outlier that proves the point — since reform began, it has lifted nearly 800 million people from extreme poverty. But beyond that exception, convergence is slow and fragile. Under shared rules and deep integration, we do not see a single road to catch-up but a hierarchy: a center that sets standards and captures rents, and a periphery that moves, slowly, within guardrails.

What this year’s Nobel says (and what it doesn’t)

Since long before Adam Smith, thinkers have hunted for the mechanics of expansion. Mercantilists equated national strength with trade surpluses; the physiocrats located “natural” surplus in agriculture. Smith reoriented the debate toward specialization and the division of labor; Ricardo formalized trade gains; Marx interrogated accumulation and class relations, treating technological change as the decisive lever that raises productivity and reorganizes labor through cooperation, machinery, and large-scale industry. In the twentieth century, growth theory turned these intuitions into models: Solow isolated capital deepening and technical progress; “endogenous” approaches put human capital, innovation, and incentives at center stage. Last year’s Nobel to Daron Açemoglu, James A. Robinson, and Simon Johnson (ARJ) offered one compact answer: growth depends on institutions, with inclusive rules fostering investment and innovation.

This year’s award to Mokyr, Aghion and Howitt offers a different answer to the riddle of growth: growth is hidden in innovation. They approach it from complementary directions, but the connection to growth is unmistakable in both their core arguments and landmark works: A Culture of Growth by Mokyr and The Economics of Growth by Aghion and Howitt. The Nobel Committee agreed: their work has now been recognized by the prize “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.”

Aghion and Howitt’s core idea is simple: economies advance because people and firms keep building better versions of what already exists. Each upgrade shoves yesterday’s technology toward the museum, so replacement is the motor, not a malfunction. Firms race to invent the next step; that race cuts two ways. New products squeeze the profits of incumbents, which can dull their appetite to invest, yet fresh ideas also spread, inspire, and lower the cost of future discovery, pulling the next round forward. Unlike older models where “technology” just fell from the sky (think Solow), Aghion–Howitt make innovation endogenous. It responds to incentives, rules, education, finance, competition and the possibility of overtaking rivals. Change those levers and you change the speed of growth.

Mokyr supplies the deep historical logic. Innovation becomes systematic only when a culture of “useful knowledge” takes root: experiment is valued, debate is open, craft and science talk to each other, and practical tinkering is legitimate. Institutions matter, but mainly as scaffolding for beliefs and preferences. Better markets or tidier rules, on their own, cannot account for modern growth; culture gives institutions their bite. That is the split from the ARJ institutionalist view: not good rules directly causing growth, but culture-shaping institutions that, in turn, sustain innovation-driven growth. Europe, in Mokyr’s account, made that leap when it discarded knowledge-as-contemplation and embraced the conviction that progress was possible, useful and legitimate — the belief that the world could and should be remade through science and technology.

Policy implications are obvious. Keep markets contestable so newcomers can challenge incumbents. Fund basic research and de-risk private research and development (R&D). Invest in human capital that mixes science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) with broad problem-solving skills. Ensure finance reaches young, risky firms. Calibrate intellectual property to reward discovery without freezing competition. Build diffusion systems so frontier ideas spread across sectors and regions. For catch-up economies, like post-socialist and developing countries, this means shifting from imitation to home-grown innovation as they near the frontier, which is the spirit of the “middle-income trap” diagnosis associated with the Schumpeterian literature. And because creative destruction creates losers as well as winners, pair this dynamism with competition policy, active labor support, and social insurance so the politics of innovation remain sustainable.

Marx, who explicitly tied growth in labor productivity to technological change, would hardly quarrel with pro-innovation basics such as R&D funding, STEM education, incubators, and diffusion support. In his account, revolutions in the forces of production — not just capital accumulation per se — reorganize work, compress necessary labor time and enable higher real output, while also intensifying conflict over who captures the gains.

Innovation’s system-neutrality sits awkwardly next to last year’s Nobel. The ARJ framework is outwardly agnostic, but its “inclusive, growth-promoting” institutions are the canonical capitalist bundle: strong private property, contract enforcement, deep private capital markets, and checks that protect owners from expropriation. That package may correlate with growth in capitalist settings, but it is not conceptually necessary for innovation-led growth as such. If the three hard conditions are met — disciplined selection, decentralized experimentation with truthful feedback and central learning, and credible, time-bound rewards with high diffusion — then a non-capitalist order could, in principle, generate Schumpeterian dynamism without importing the full ARJ constitution.

Convergence isn’t happening the way textbooks promised

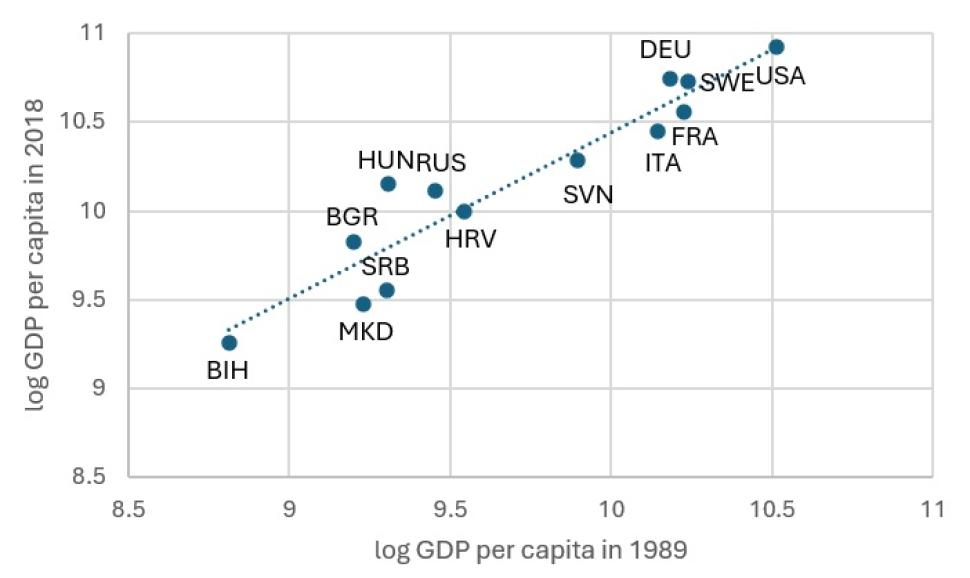

Three and a half decades of post-socialist capitalism have not delivered any clear superiority on either convergence or frontier innovation. On convergence, the picture stays fractured: Europe behaves like clubs, not a single track, with a stubborn center–periphery split.

Figure 1 shows a tight upward slope; that is, high rank persistence. Post-socialist economies (Hungary, Russia, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina) cluster on or below the fitted line and fall well short of the core group (United States, Germany, Sweden, France, Italy). A couple sit slightly above the line (minor over-performance), several sit below it (under-performance), but none leap into the core cluster. That is not decisive catch-up; it is position-keeping.

A large empirical literature finds no overall real-income convergence across the EU. Instead, economies sort into “clubs” that march toward different steady states, with regional linkages and historical position shaping who clusters with whom. Crucially, technology sits at the core of this sorting. Post-socialist and newer member states differ systematically from the old core in production structure, sectoral specialization, and the organization of learning.

Benchmarking to the euro-area 20 (EA-20) — a richer, more technology-intensive reference point than the EU average — today’s pace means catch-up takes generations (index = 100 × country GDP per capita in PPS ÷ EA-20; speed = average yearly change in that index over 2010–2024). Serbia’s recent gain of about 0.42 index points a year puts parity around 2215. Croatia would close its gap in roughly 55 years (about 2080). North Macedonia, moving far more slowly, would need roughly three centuries (around 2348). Even among neighbors, the “club” pattern holds: some move faster, some barely move, and there is no single road everyone travels together along.

Studies of the EU-27 attribute much of the income gap between new and old members to differences in total factor productivity, rooted in technological heterogeneity. Over the past two decades, the incumbent core has specialized in knowledge-intensive services while progressively offshoring lower-tech manufacturing to Central and Eastern Europe. The result is a structural split in Total factor productivity (TFP) levels and growth rates, and with it, a durable center–periphery pattern inside the single market — a dynamic Marx, and later dependency theorists, would immediately recognize.

Stepping beyond Europe, Dani Rodrik argues that periphery growth depends less on how fast the core expands and more on the size of the productivity “convergence gap,” which remains large. But the old escalator is weaker: frontier innovation has turned sharply labor-saving and global value chains meter diffusion, thinning the job intensity and domestic linkages of latecomer manufacturing. Catch-up therefore requires sustained structural change into tradables with learning content — manufacturing and modern services — backed by policies that raise productivity in the broad base of firms rather than a few export enclaves. Even where growth outpaces the core, the starting distance means full convergence is a generational project, not a planning-cycle deliverable.

The innovation conversion gap

Mainstream convergence theory rests on diminishing returns: poorer economies should enjoy higher marginal returns to capital, so with the “same” inputs they grow faster and eventually catch up. The catch is in that word “same.” It presumes comparable inputs across countries, yet dependency theory shows they are not: the capitalist core structures and restricts access to the very complements that make R&D productive: technology, finance on decent terms, IP and standards, skilled networks and market access. So, the periphery cannot convert effort at the same rate.

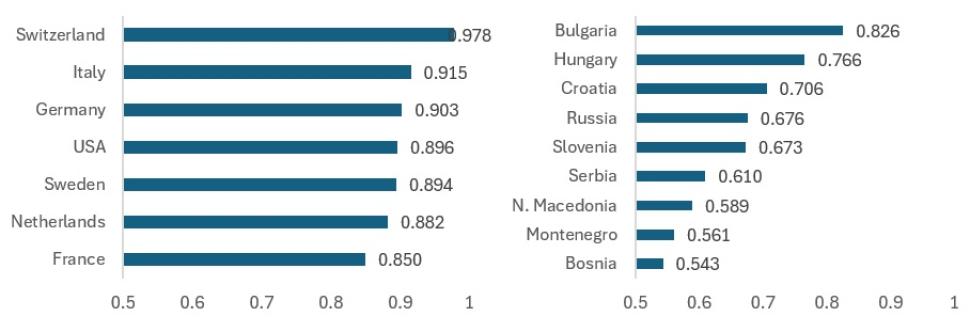

To measure that conversion, I use WIPO’s Global Innovation Index 2025: inputs are the GII Input Sub-Index, outputs are the GII Output Sub-Index, and conversion efficiency is the output-to-input ratio rescaled so the global frontier equals 1.000 (Figure 2). On that yardstick, innovation-frontier economies convert a very large share of inputs into outputs close to unity (Switzerland 0.978; Germany 0.903; United States 0.896). Even the best catch-up performers from the European non-core trail (Bulgaria 0.826; Hungary 0.766; Croatia 0.706). Southeast Europe lags further (Slovenia 0.673, Serbia 0.610, North Macedonia 0.589, Montenegro 0.561, Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.543).

The two panels make the point starkly: the level gap is joined by a conversion gap. Despite increased effort, most developing countries are not approaching the frontier’s efficiency in turning innovation inputs into outputs. Convergence stalls twice — first on resources, then on translation capacity. From a dependency perspective, this is a structured asymmetry: the “same inputs” assumption fails because the core controls access to the complements that enable innovation and technological progress.

Innovation under socialism

So, the innovation engine has, by and large, failed the new capitalist countries emerging from “real socialism”. But the socialist experience was also unsatisfactory. Why? Any order must supply three hard conditions for the innovation engine to hum. First, disciplined selection: the capacity to terminate failing projects and reallocate people and resources quickly. Second, decentralized experimentation with truthful feedback and central learning: many parallel bets, transparent metrics, and channels that transmit bad news without punishment. Third, credible rewards that spur problem-solving without enclosing knowledge: time-bound rents or prizes, promotion ladders, and procurement that pays for results while keeping diffusion high.

These conditions were not fully met in “real socialism” in either the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia or other socialist countries. Resource allocation was steered by policy and coalition needs rather than performance; soft budgets dulled selection; ministerial and party interference (often along republican lines) distorted signals; and inefficiencies accumulated, yielding technological stagnation outside a few defense-related islands, such as the aircraft industry. A second, complementary mechanism compounded the problem: structural and technological mismatch. The model that excelled at forced industrialization struggled to adapt to the scientific-technological revolution, locking socialism into structural lag. Chronic shortages were caused not simply by soft budgets but by “processes of compensation,” in which deprived sectors embedded low-quality inputs into their technologies, overconsumed mass resources and indirectly drained advanced sectors.

None of this, however, proves socialism unfeasible; on the contrary, as the title of Alec Nove’s book Economics of Feasible Socialism reminds us, it clarifies what must be built. First, even where selection was blunted and signals were noisy, technological progress still occurred across socialist experiences: productivity rose, complex industries emerged, and sizable science–engineering capacities were formed. The real indictment is not the absence of progress but weak mechanisms to steer it, scale it, and diffuse it widely.

Dependency mechanics now

From a dependency vantage, the bottleneck is not “domestic failure” but externally structured scarcity of critical complements to innovation. Today’s technology conflicts harden the asymmetry of power between the core and the periphery: export controls on advanced semiconductors and tools; screening of FDI and research ties; standards wars over 5G, AI, and clean-tech supply chains; and chokepoints in lithography, EDA, and specialty materials. These are not background conditions. They set the feasible frontier for latecomers.

Over the past few years, this has been painfully clear. On health technologies, World Trade Organization (WTO) members agreed only a narrow temporary easing of TRIPS rules for COVID-19 vaccines in June 2022, and then failed to extend it to diagnostics and therapeutics, preserving core patent gatekeeping when diffusion mattered most. This is not neutral rule-making; it entrenches lead-firm control of “core technologies” and the rents around them.

On general-purpose technologies, the United States has paired subsidies with extraterritorial export controls that restrict China’s access to advanced chips and the tools to make them (the October 2022 rules and subsequent tightenings), while conditioning CHIPS Act funding on limits to capacity expansion in “countries of concern.” As Benjamin Selwyn argues in his piece on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, recent US strategy targets chokepoints explicitly, aiming to “strangle” segments of China’s tech stack while keeping a “small yard, high fence” around dual-use capabilities.

Europe has moved in parallel toward defensive industrial policy, including definitive countervailing duties on Chinese battery-electric vehicles, tightening market entry on terms set in the core. Whatever the merits in trade-law prose, the effect is straightforward: control the standards, the capital costs, and the lead-firm gateways, and you control conversion at the periphery.

The conversion gap, previously highlighted, persists because access to the complements that make R&D productive is rationed through a small set of chokepoints. First, technology and IP monopolies concentrate control over general-purpose techniques and standards, generating technological rents and metered diffusion (Samir Amin’s “monopoly of technology”; Ernest Mandel on monopoly capital’s rent extraction). Second, transfer is routed through controlled channels: export controls, licensing with narrow fields of use, black-box equipment, and lead-firm governance of value chains that deliver assembly without design, so learning remains thin (Andre Gunder Frank’s metropolis–satellite integration that blocks autonomous capability formation). Third, command over finance and critical inputs raises the periphery’s cost of scaling: frontier finance is cheaper and longer-tenor; upstream tooling and software chokepoints throttle entire production functions; skilled labor and data/compute pools are enclosed (Mandel’s late-capitalist concentration; Rudolf Hilferding’s finance capital as coordination power). Fourth, rule-making locks in hierarchy: trade and IP regimes, standards and certification, and selective protectionism police entry after the core has climbed, the historical pattern Ha-Joon Chang calls “kicking away the ladder” and Jason Hickel critiques as a ruleset tilted to incumbents.

As Boris Kagarlitsky argues in The Long Retreat, core dominance does not just ration technology; it skews institutional evolution in the periphery, rewarding coercive, patronage-heavy and rent-seeking arrangements that “advanced” capitalisms have largely disciplined at home. The result is institutional imitation without convergence: a veneer of best practice laid over extractive routines calibrated to subordinate insertion in global value chains.

This matters for how we interpret the Nobel prize. If innovation is the engine, then engines are mounted in very different vehicles. In the core, capability accumulates around R&D networks, standards, and high-margin services. In the periphery, production is slotted into global value chains where learning, rents and bargaining power are rationed.

For non-capitalist (socialist) development, the question is therefore not simply how to “add innovation”. It is whether an alternative regime can “delink” from the core, overcoming peripheral insertion into global value chains and the political economy of embargoes, standards, and IP enclosures. Dependency theory has been saying the quiet part out loud for decades: where you sit in the world system conditions what you can learn, make and keep. Any serious strategy must confront three linked facts: persistent club dynamics, technology-driven divergence within integrated markets, and tightening geopolitics of knowledge.

Conclusion

Would Marx approve of this year’s Nobel? Partly. He would endorse the central claim: innovation transforms the forces of production and, with them, the possibilities of growth and social development. In the words of Capital, modern industry’s “technical basis is revolutionary,” perpetually overturning methods, skills, and the division of labor. He would also be comfortable with the Schumpeterian cadence of waves and disruptions; much of that rhythmic logic is foreshadowed in his own account of technical change and reorganization of labor.

But he would reject the neutrality story. Under capitalism, the gains from innovation are allocated by power: capital captures the rents while labor bargains over crumbs. The very same innovations that could shorten work, lighten effort, and broaden prosperity become, under capitalist command, instruments for longer hours, intensified labor, and wealth concentration. Or as he put it: what is “in itself a victory of man over the forces of nature” becomes, “in the hands of capital,” a victory over the worker.

Internationally, the same logic scales up. The capitalist core guards the command heights of knowledge and technology, rationing diffusion and “kicking away the ladder,” so the periphery’s inputs do not convert like the core’s. Marx would say the engine is real; the ownership and rules around it decide who moves.

On Marx’s reading, the lesson is not to worship innovation but to socialize its fruits. The transformative power of technology can be fully unlocked only when production is organized for social needs rather than private appropriation — when diffusion is a design principle, not a residual; when learning, capabilities, and bargaining power are broadly distributed; and when international rules stop manufacturing scarcity. In that world, the Nobel’s engine still hums, but it moves a different vehicle.