Class war in Romania: Austerity and the dismantling of trade unions

A wave of austerity measures were implemented in Romania in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and subsequent Eurozone crisis. They represented another example of how austerity policies are nothing more than disguised class war on the working people. Austerity has been the perfect tool used by elites to dismantle the remnants of socialist era workers’ rights and completely cripple the trade unions. In this article, I will explore what this turbo-austerity program implied and its impact on trade unions in Romania. I will also analyse recent changes in legislation, dating from 2022, and how they may provide trade unions with renewed momentum today, as the country undergoes another austerity wave.

The long transition to capitalism

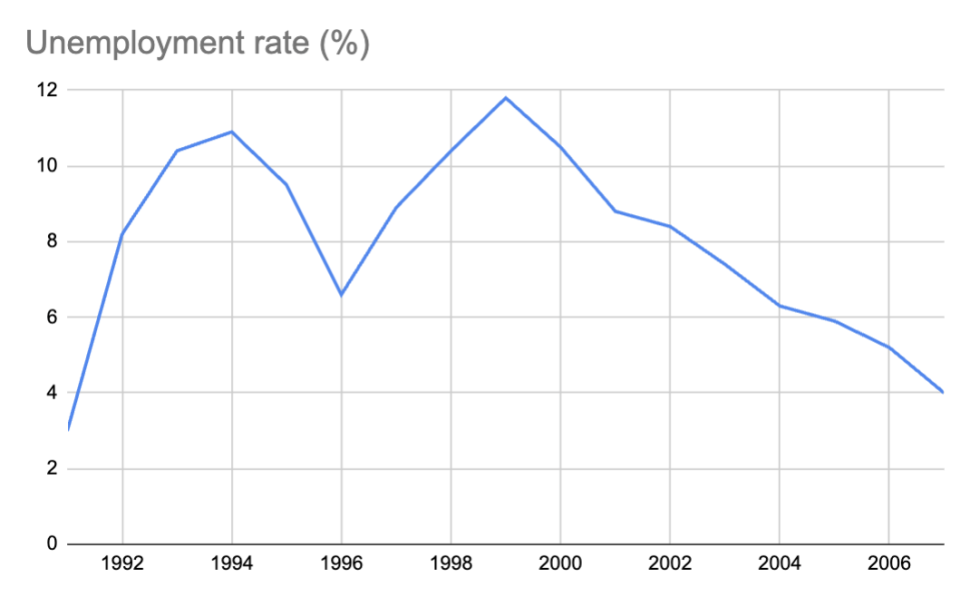

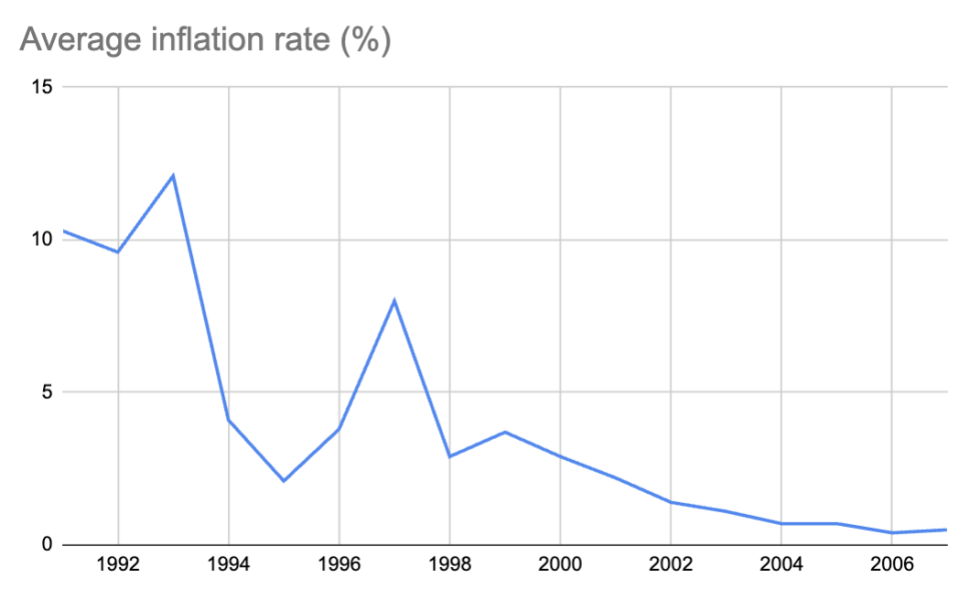

In the first 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the start of the “transition to capitalism”, Romania went through endless “reforms” meant to bring the country into the realm of the “developed” and “civilised” capitalist countries. These included the privatisation of dozens of state-owned companies, mostly through shady arrangements between politicians and business owners, which resulted in mass unemployment (see Figure 1). It also consisted of the devaluation of the local currency (Leu) and inflation rates of up to 12% in 1993 (Figure 2). These reforms were part of the Structural Adjustment Programs and Stand-by Agreements with the IMF, but also a requirement for Romania to join the European Union.

While in the 1990s there was no end in sight for this instability, the mid-2000s seemed to bring some stability, with Romania receiving EU member status in 2007. But this hopeful period was short-lived: the Global Financial Crisis hit Western economies in 2007-2008, and while it was not felt immediately in Romania due to its peripheral status in the global economy, its impact began to be felt in 2010. Indeed, Romania’s economy mostly relied on remittances from Romanians working in Spain and Italy — two of the countries hardest hit by the crisis. The subsequent Eurozone crisis further impacted remittances, and proved fatal for Romania’s trade unions and workers’ rights.

The 2010 turbo-austerity: A blueprint for class war

In 2010-2011, Romania experienced one of the most dire austerity programs in the 21st century — one less talked about than Greece’s austerity program under the diktat of the Troika, yet similarly destructive. The usual suspects were behind the plan, the IMF and the EU, imposing austerity measures in exchange for a 20 billion euro loan.

The austerity package was justified as “needed in order to reduce the public deficit” (6.5% of GDP in 2010). It was led by then-Prime Minister Emil Boc, under the presidency of Traian Basescu, both from the “liberal” right-wing Democratic Liberal Party (PD-L). The austerity package involved slashing public-sector wages by an incredible 25%, and old-age pensions by 15%.

Back then, the minimum wage was 600 lei (about 143 euros or 182 USD) while the minimum retirement pension was 350 lei (83 euros, 106 USD). Moreover, in 2010, absolute poverty affected 1.1 million people, out of a total population of 20.2 million (5.5%), while the population at risk of poverty was 41% of the population.

These measures were imposed undemocratically: the PM “assumed responsibility” through Article 114 of the Constitution, bypassing any parliamentary scrutiny (a common practice in Romania, showcasing a complete deficit of democracy).

The 2011 Social Dialogue Law and the demise of trade unions

The response from trade unions was swift: the early 2010s represent a period of resistance to austerity on a scale unprecedented since the 1989 “Revolution”.

The major trade unions managed to (separately) mobilise public-sector workers, pensioners, and pregnant women and mothers, whose child benefits were going to be slashed, for several large-scale protests lasting from the spring of 2010 until late autumn that same year. The protests peaked on October 27, when between 50–100,000 people protested in front of the government building (Victoria Palace). Pensioners took to the streets to protest because they had no money for medication. Public servants went on strikes to demand fair wages.

All these manifestations were met with violence from the Jandarmerie (a law enforcement institution, similar to the French Gendarmerie, belonging to the Army). Interestingly, the Police force also protested against austerity, though it was not repressed by the Jandarmerie. As a consequence of the September 24 protest, Interior Minister Vasile Blaga resigned while the Chief of the Bucharest Jandarmerie was demoted because he refused to intervene against the Police protest. Then, the Jendamerie decided to join the protesters and ensure they could protest free from repression.

Trade union power seemed to grow after this wave of protests. Though the past 20 years had not been easy for trade unions, with the media constantly portraying them in a negative light, the 2010 protests had shown to public sector workers that there was power in numbers. However, the government and employers’ associations had other plans. The government was more prone to discussions with employers than trade unions. As such, most of the labour law reforms after 1989 were undertaken by the government following intense lobbying by employers’ associations.

This was also the case in 2011, when the Social Dialogue (SD) Law No. 62/2011 was passed. The SD law dismantled the collective bargaining procedure at the national level: up until then, 100% of employees from both public and private sectors were covered by a national-level unique Collective Labour Agreement (CLA), making Romania one of the few countries in the EU with such coverage. Following the 2011 SD law, coverage was slashed to 15% and CLAs were only possible at the sectoral level.

The SD law also included other restrictive measures, such as raising the representation threshold of a trade union to 50+1% of employees in a company or a sector (branch of activity). It also made it more difficult to form a union, requiring at least 15 employees from the same company. This was done in a context where 90% of Romanian companies had less than 9 employees.

The right to strike was also negatively impacted: the law introduced a series of administrative requirements, including needing 50+1% employees willing to go on strike (close to impossible to achieve), and introduced the concept of an “illegal strike” in cases where trade unions did not gathered all the administrative paperwork needed to initiate a strike. An “illegal strike” carried with it serious legal consequences, and was deemed a felony. Moreover, the law made solidarity strikes illegal (solidarity strikes are strikes started by workers at a company in solidarity with their comrades at a different company, or even in a different economic branch, who are already on strike).

The 2011 SD law was essentially capital’s counter-offensive against the increased power of organised labour that had resisted an austerity program meant to restore capital’s profitability in the wake of a crisis. The law was designed to cripple workers’ ability to collectively resist (collective bargaining, strikes) against the increased extraction of surplus value. This legal offensive was needed to create the “ideal” conditions for capital accumulation: a working class stripped of its power to collectively bargain cannot but accept a smaller share of the wealth it produces.

The impact of the law was devastating for trade unions. Over the course of 11 years, confidence in trade unions diminished and membership plummeted to less than 20% in 2013 (down from about 40-45% in 2008). By losing their ability to go on strike and form new trade unions in smaller companies, trade unions became a shell of their former self.

The impact was felt at the personal level as well: in my interviews with older trade unionists, now in their 50s-60s, they are very pessimistic and have lost hope, while young trade unionists do not have a very strong culture of trade unionism. There are very few young people in trade unions, and need serious capacity building to bring them up to speed to what trade unions need.

New hope against old capitalist tricks

So badly were trade unions affected that even the European Commission started to be alarmed. In 2022, the EC warned the Romanian government that its labour law was so skewed in favour of employers that it risked causing permanent damage to societal cohesion, and that there was a high risk of unrest in the coming years. As such, the EC conditioned access to the National Recovery and Resilience Plans to the passing of a new Social Dialogue law, 367/2022, which although not perfect, is much friendlier to TUs.

It maintains the concept of an illegal strike, but gives trade unions a 24-hour window to resolve any administrative issues and ensure their strike is legal. It also allows for solidarity strikes, and has lowered the representation threshold to 35% for negotiating a CLA and initiating a strike. It also allows new trade unions to be formed in companies with 10+ employees or by 10+ employees from different companies but belonging to the same economic sector (as defined by NACE code). While this law is not a panacea, it gives trade unions some room for manoeuvre. Nevertheless, decades of attacks has left a permanent scar on Romanian trade unions.

Today, we are witnessing more austerity in Romania. Complaining that the public deficit is too high (9.7% of GDP), the government has started another austerity wave. The first package of measures was passed in the summer of 2025, which saw the freezing of public sector wages and all retirement pensions until the end of 2026 (essentially a pay cut as inflation keeps rising); a freeze on all hirings in public sector jobs; a rise in the VAT (a regressive tax on the poor); and the removal of access to public health insurance for dependants (stay-at-home mothers, elder parents without pension, people with disabilities, etc). The package also included a doubling of taxes on capital, but which were very low to start with: taxes on dividends went from 8% to a timid 16%, while taxes on banks’ profits went from a minuscule 2% to a tiny 4%.

A second package focuses on “increasing public administration’s efficiency” by firing 10-30% of public servants in some services, as well as increasing tax collection capabilities and reducing expenses in the public healthcare sector. However, the package has not been adopted in its entirety because it also contained provisions for increasing the pension age for magistrates (currently at 48 years of age) to 65, like the rest of the population, as well as lowering their special pensions (currently an average of 4000 euros monthly while the average public pension is 370 euros a month.)

So far, trade unions have not initiated significant strikes nor have there been mass protests like in 2010. There have only been small weekly pickets during the summer, which peaked on September 8 when a 10,000-strong protest took place in Bucharest. The trade union confederations also managed to agree to hold a major protest on October 29th, with four out of five confederations participating.

The conditions are ripe for a real class war in Romania — the material basis for public discontent is obvious. But in the absence of a socialist alternative to channel popular anger into a coherent anti-capitalist strategy, the far-right “populist” party AUR (Alliance for the Union of Romanians) is monopolising the discourse on relevant issues (housing, wages, poverty, etc.) while distracting popular anger away from the capitalist class towards scapegoats (migrants, “the globalists”) and organising endless protests in favour of far-right presidential candidate Calin Georgescu.

There is a clear need for a united front of the left in Romania. The small pockets of left-leaning and Marxist groups must coalesce and overcome their petty theoretical disputes. They must overcome their Professional-Managerial Class (PMC) origin and integrate more blue-collar workers and trade unionists, in order to help trade unions rebuild the organisational capacities they lost in 2011. With the spectre of AUR looming large, our task as socialists is to reclaim the narrative of discontent, transforming the fight against austerity from a series of financial demands into a unified political struggle for working class power.

Maria-Luisa Guevara is a nom de guerre of a Romanian researcher and activist for housing rights, workers’ rights of non-European workers and progressive issues in general. You can read here writings at on Substack.