Revitalizing popular counterpower in Venezuela: Tensions between the PSUV and popular organizations

Abstract

This article asks if, and to what extent a movement organization or party has emerged with the capacity to challenge the leadership of Venezuela’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). The article contributes empirically (case study analysis of party-popular organization relations in Venezuela), and theoretically (developing a theory of popular resistance struggles where left parties renege on promises). Drawing from interviews with figures from communes movements, leftist parties, former/current PSUV figures, and participants in popular organizations, the article details the challenges facing critical sectors today.

Utilizing an array of tactics (clientelism/co-optation/parallelism/repression) the PSUV has controlled popular organization capacity to challenge the party. Moreover, the article details numerous efforts to ensure a rival party cannot challenge the PSUV from its left. The article also discusses the Future Movement — a new party which has emerged from the PSUV. Though PSUV figures suggest it offers an electoral option for critical Chavistas, our interviewees remain skeptical.

IntroductionAbstract

“Gallina vieja esa gente, ni pone, ni deja la culequera” 1

Ali Primera

Venezuela’s “Bolivarian Revolution” is at a critical juncture. Under an increasingly authoritarian government and a state dominated by Nicolás Maduro and his allied sector of the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (United Socialist Party of Venezuela, PSUV), with presidential elections in 2024 that witnessed the government fail to release results which indicated a severe loss for the PSUV while Maduro claimed victory, and with a continued economic crisis ravaging the country, Venezuela’s Chavista project faces stark challenges and dilemmas.

Efforts to respond to Hugo Chávez’ calls for the construction of a “communal state” in his famous Golpe de Timón (Strike at the helm) speech have faced major impediments as popular organizations have confronted a supposedly-allied party and institutional sphere. Indeed, exclusionary political processes and neoliberal-style economic reforms (not to mention state-sponsored repression of critical popular voices) enacted under PSUV-governments indicate a wholesale abandonment of the fundamental principles of the Chavista project (Brown, 2022; García-Guadilla, 2020; Rosales y Jiménez, 2021).

Consejo comunales (communal councils) and comunas (communes) have been, to varying degrees, in confrontation with, absorbed by, divided by, and ignored by the ruling party and constituted power. That is, the construction of popular power, “understood as a process through which organizations and social movements autonomously make decisions about public issues” via consejos, comunas, and other social organizations (García-Guadilla and Castro, 2022: 90) faces uncertainty in the current conjuncture. It is at this critical moment facing progressive Venezuelan forces, in which popular power has been weakened, co-opted, bureaucratized, and demobilized that we must address the issue of if, and how, popular power is capable not only of surviving but also of re-shaping the pathways forward out of the current mire.

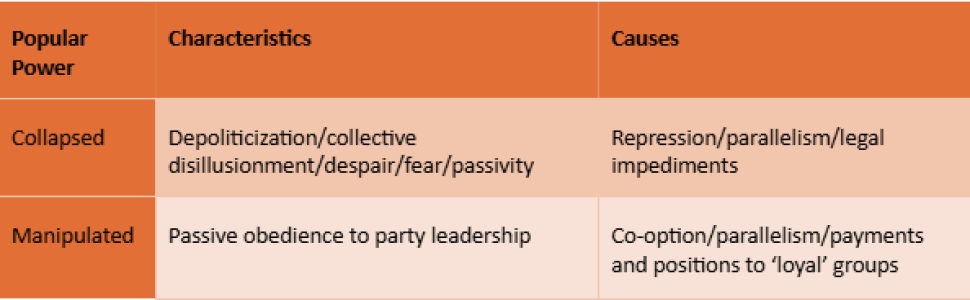

While there have been excellent case studies of the communes (Ciccariello-Maher 2016; Azzellini, 2018), such appraisals require updated empirical analysis underpinned by qualitative investigations that bring in the voices of key actors and promoters of communes in the current moment (for a similar approach, see Brown, 2022; García-Guadilla, Torrealba, and Duno-Gottberg, 2022; Jiménez Lemon, 2022; Bracho, 2022; Torrealba, 2022). Indeed, Ulises Castro (García-Guadilla and Castro, 2022) outlined three scenarios facing popular power following twenty years of evolution; collapse, manipulation, and revitalization.

The collapse scenario sees popular power squashed as a result of “depoliticization, collective disillusionment, hopelessness, discontent, self-preservation, uncertainty, fear, and passivity” (García-Guadilla and Castro, 2022: 94). In the second manipulation scenario, “passive obedience to the governing party and institutions becomes more widespread and a clientelist loyalty develops,” leading to the eradication of popular power. Finally, revitalization would see popular power reinvented as “resistance and struggle with active and radical critique, reclaiming autonomy and the right to dissent” (García-Guadilla and Castro, 2022: 94).

Our argument suggests that to move toward the revitalization-resistance pathway of popular power requires two steps. First, where collapse or manipulation scenarios have been reached, it is necessary to challenge disillusionment and depoliticization in order to encourage the (re)engagement of people with spaces of popular participation. Passive, unconnected citizenries cannot generate sufficient pressures to re-claim and re-direct the Chavista project. Moreover, manipulation and passive obedience must be corrected, with clientelist party-base linkages rejected.

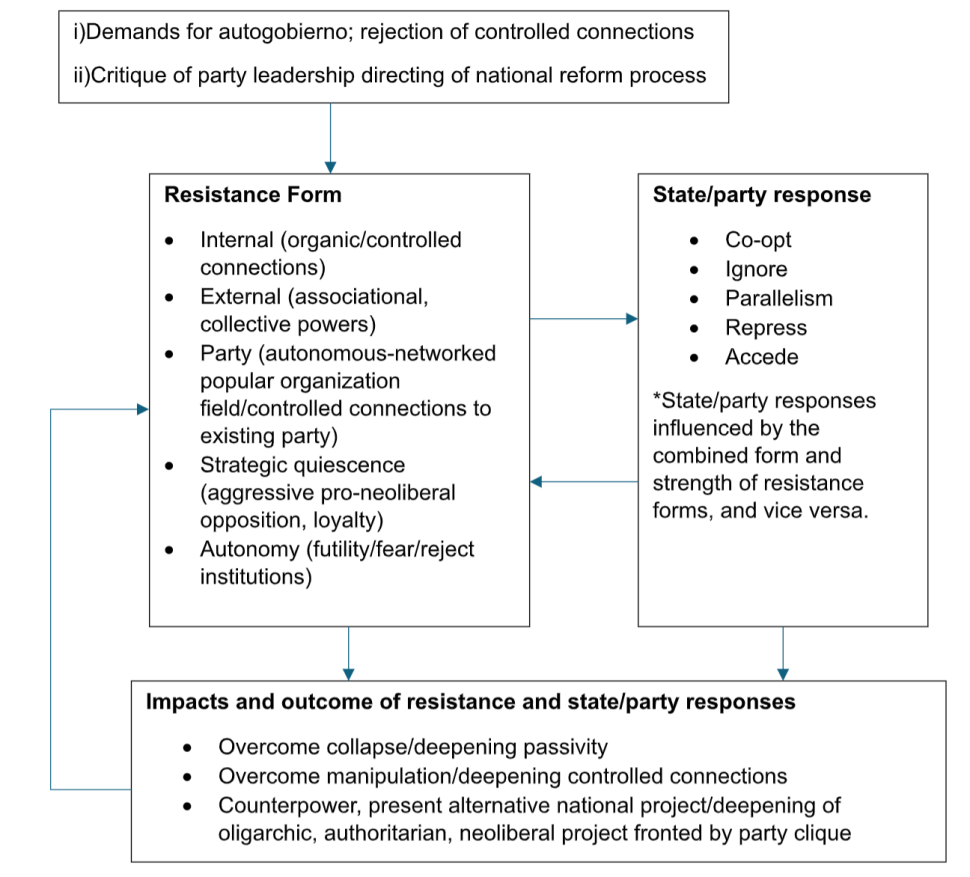

The second step toward revitalizing popular power moves beyond the collapse/manipulation scenarios and focuses on active critique of the PSUV-leadership’s directing of the process. While critique must focus on overcoming issues of collapse/manipulation in order to regenerate spaces of active and un-coopted participation, resistance must go beyond simply fostering autonomy. Revitalizing popular power entails the construction of a popular counterpower — a critical wing of the Chavista project capable of challenging the bureaucratizing, authoritarian, neoliberal process headed by Maduro and his allies. Hence, revitalizing popular power entails demands for autogobierno (self-government) at the local level, in order to begin the process of building counterpower at the national level.

We need to ask the question of if, how, and why a revitalization of popular power is underway. The following section advances a framework for analyzing empirical cases. Next, a brief methodology discussion is offered before attention turns to the Venezuelan case. The article concludes with a discussion of key findings and suggestions for future research.

‘Creative tensions’ between constituted and constituent power: Popular power as resistance inside and outside the party

Over the course of left-led processes in Latin America in the past two decades, relations between ruling left parties and constituent movement organizations followed complex paths, drawing attention from an array of scholars interested in the role of movement organizations in fostering space for parties (for example Silva, 2009; Roberts, 2014; for Venezuelan case, see Ciccariello-Maher, 2013; Fernandes, 2010; Velasco, 2015; Cannon, 2009; Brown 2022); left populism (for example Munck, Mastrángelo and Pozzi, 2023; Brown, 2023); party-movement relations (for example Anria 2019); incorporation strategies (Silva and Rossi, 2018); and participatory democracy (for example Hetland 2023; Cameron, Hershberg, and Sharpe, 2012). Party-movement organization relations under left-led governments in Latin America have also been the focus of scholars concerned with issues regarding critique of left-parties from popular movements, with particular focus on efforts by party leaders to control, pacify, and demobilize critical voices (Brown, 2024; Gaudichaud, Modonesi, and Weber, 2022).

Underpinning these literatures is the issue of whether party-movement organization relations are forged so as to deepen or inhibit democratic quality for long-excluded popular sectors. Party-base relations have entailed complex and nuanced “creative tensions” between resistance and convergence, between movement autonomy and engagement with left parties (see Ellner, Munck, and Sankey, 2023) as constituent power has been simultaneously supported and restricted by constituted power (Ciccariello-Maher, 2013a; Brown, 2020).

These authors highlight that to counterbalance moderation of the leftist project and/or oligarchization, developing a popular force that is capable of influencing national politics is vital. That is, permanent critical oversight of party leaders by grassroots partisans and popular organizations is crucial for the maintenance of accountability. While moderation, oligarchization, and top-down meddling in popular organizations may trigger resistance from below, the very nature of top-down control mechanisms may shape the nature that resistance takes. In turn, the nature of popular resistance (form and strength) shapes the responses by party leaders. Although many popular organizations may choose not to interact with or pressurize party leaderships or elected officials, for those that do there are two (interconnected) avenues — internal and external — to achieve this.

Challenging party leadership from within: organic ties and autonomy

A party’s “organic connection refers to the existence of formal or informal linkages with autonomous organizations of the core constituency and to the party organizational traits that grant power to social actors in the party to constrain leaders’ decisions” (Anria et al., 2022: 386). The authors’ concept of organic connection has three principal attributes.

First is the existence of autonomous social actors who constitute the core constituency of the party. Second, there must be formal linkages between the party and these social organizations (such as party statutes that institutionalize the participation of social organization movements in the party structure) or informal linkages (such as movement organization leaders/grassroots activists having dual membership in the party and their constituent organization; popular organization leaders may also have strong informal ties to party leaders). Third, the party structure must grant power to social organizations’ interests in constraining party leaders’ decisions (voice) in party decision making bodies.

The autonomy of organizations implies that they have “the capacity to set and communicate their preferences, regardless of the opinions of the party leaders” (Anria et al., 2022: 388). Autonomy also requires that leaders of popular organizations are not subordinate to or co-opted by party leaders. Cooptation of organization leaders who enter the party structure raises the possibility that these leaders become more responsive to party leadership concerns than their constituent organization’s grassroots’ concerns. Autonomy from the party also means that popular organization survival is not dependent on party funding.

Challenging the party from outside: Mobilization and alternative political vehicles

Contestatory mobilization refers to street demonstrations, road blocks, strikes or any form of contentious action by allied- or formerly-allied constituent organizations. Unlike defensive mobilizations from sectors of the party’s base that emerge to support the ruling party in the face of opposition, contestatory mobilizations overtly challenge the actions of the party leadership. The form that contestatory mobilization may take will be influenced by the associational and collective power of popular organizations (Silva, 2009).

Associational power refers to organizing along lines of class, identity, race, or other specific interests into unified and united organizations. High levels of associational power indicate a strongly-organized civil society with high organizational density. Organizational density may refer to the percentage of total labor organizations that are members of a labor confederation or the percentage of a region’s population that are members of a movement organization, for example. Unity of purpose and dense membership numbers indicate high associational power, internal organization factionalism and tension and/or low membership bases indicate weak associational power.

Collective power refers to instances where distinct organizations forge tight horizontal connections in which they may retain their independent organizational status but unite around a common agenda. That is, collective power indicates a unity of purpose across organizations whereby broader, common interests and goals are privileged over narrow organizational interests. Overlapping membership and close contacts between leaders of different movement organizations may facilitate the building of collective power.

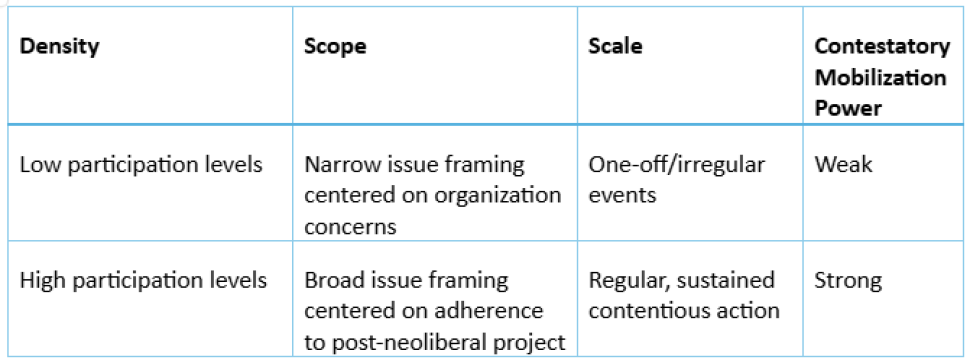

Contestatory mobilization can be conceptualized as existing on a continuum running from weak to strong depending on the density, scope, and scale of contentious action. Density refers to the numbers of people participating; scope relates to whether narrow organizational concerns or broader popular concerns are foregrounded; while scale refers to the duration and pattern of mobilization (one time, repeated, or sustained cycles of contestation).

New political vehicles may be launched to resist via the ballot box. Popular organizations, whether they take the form of social movements, labor unions, or neighborhood networks have been found to offer emergent parties vital mobilizational infrastructures alongside potential core constituencies and committed partisans (Giusti-Rodríguez, 2023; Anria, 2019; Levitsky et al., 2016). However, even where preexisting networks of popular organizations exist, launching a new leftist party that challenges an already existing left party will likely be a tough challenge for critical popular organizations.

The capacity to do so will be heavily influenced by the nature of linkages between the existing left party and popular organizations. Where linkages based on clientelism and cooptation of social leaders are common, those critical organizations seeking to launch a new party will likely face reluctance/rejection from the organizations and their participants that share close links to the existing party. Splitting the popular base and the potential network of popular organizations into competing blocs — one loyal to the existing left party and one seeking to launch a new political party — stymies the scope for launching a new party capable of generating cross-territorial support.

In sum, popular power revitalization requires challenging entrenched collapse and manipulation scenarios, before engaging in resistance. Resistance is understood as a rejection of party leadership deviation from foundational promises to respond to popular movement organization demands for an anti-neoliberal and participatory project. Resistance may take a number of forms — internal and external. Internal resistance requires the existence of organic party-movement organization linkages to allow for voice and influence from below to push and influence party leaderships. Where clientelist-controlled linkages exist, it is less likely popular organizations will offer resistance to party leaderships, and indeed, linkages may be actively utilized by party leaderships to inhibit resistance. External critique may take the form of contestatory mobilization. Associational and collective power must be high to foster contestatory mobilization that is regular, high density, and broad in scope. Low levels of associational and collective power are more likely to foster weak contestatory mobilization with less influence on party leaderships. Resistance via a new political party requires utilizing networks of popular organizations as a launching pad and the breaking of any existing controlled linkages.

Beyond evaluating internal or external resistance, it is important to account for strategic quiescence due to loyalty to the project, or due to the existence of a pro-neoliberal opposition seeking to capture moments of popular discontent. Finally, resistance may not be evident due to popular organization withdrawal from institutional politics (due to fear, sense of futility, or belief in autonomous pathways).

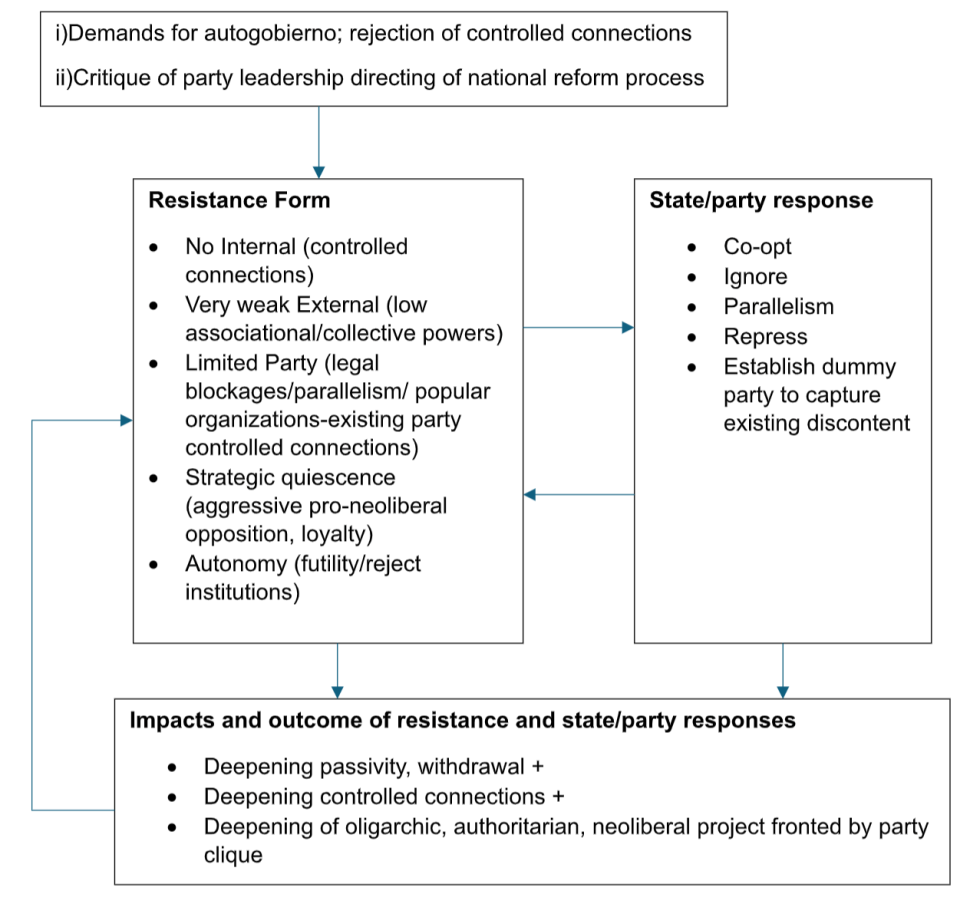

elaboration)

Data sources

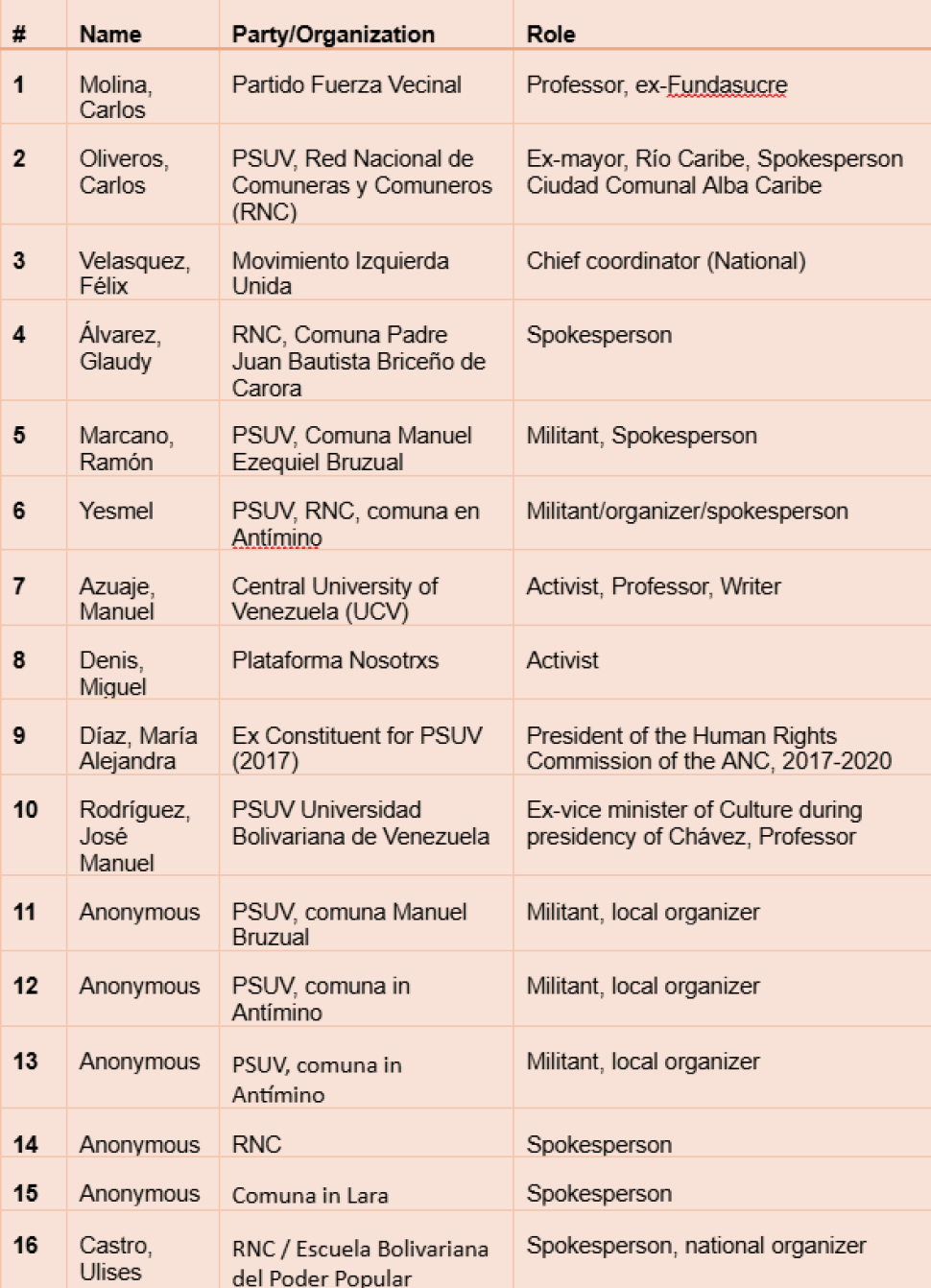

In addition to data collected through analysis of newspaper reports, Twitter accounts and speeches of elite actors, the case study analysis is based on data collected through semi-structured interviews conducted between February and May 2024. Interviewees included organizers and community activists at the national and local level; people with a dual role in the PSUV and popular organizations — including people who support Maduro and those who do not; leading figures from rural and urban communes; former senior PSUV officials in ministries, as well as elected mayors; popular educators; leaders of left-wing parties; and other recognized figures of the Venezuelan left. We attempted to contact several current PSUV officials, but most did not respond to interview requests. Those who responded seeking more information stopped responding once we described the nature of the research. Details of the interviewees can be found in Table 2. Given the repressive nature of the government, we have chosen to anonymize several of the interviewees.

Popular counterpower in Venezuela

Collapse and manipulation

In the aftermath of the pandemic which flattened popular organizing (Yesmel, interview, online, April 18, 2024), with US sanctions deepening the already existing economic crisis, with extraordinary levels of emigration, and in an extremely polarized political context, conditions were not conducive to popular power revitalization in 2024. Beyond such debilitating contextual factors, however, several other issues fostered a severe collapse and manipulation of popular power.

The linkages between consejos and comunas and the PSUV-state became increasingly controlled in recent years. Félix Velasquez (interview, online, April 22, 2024) suggests that despite an initial burst of popular power and organizing in the consejos and comunas, “just as happened with the neighborhood organizations of the 1980s that fell under the control of [Christian democratic party] COPEI, the same thing happened with the consejos as the PSUV controls and mediates them.” A “co-opted and tutelary” relationship developed as the PSUV directed the spaces of popular organizing rather than vice versa — “the party took complete control of popular organizations. It directs them, controls them, calls them to march” (JM Rodriguez, interview, online, May 22, 2024). The “PSUV, which I am a member of … Today all it does is give orders … To keep recruiting, filling out forms. It is not the same as when Chávez was here. Now the party just wants to dominate and control the consejos and comunas” (interview 12, April 19, 2024).

The opinions of the majority of our interviewees confirmed that linkages between the PSUV and popular organizations exist in both formal and informal forms (party statutes that call for participation, dual memberships in party/popular organization, close ties between some party leaders and popular organizers). However, these linkages are not organic connections. The party structure does not grant voice or veto powers. While there are tight linkages between the PSUV and consejos and comunas, the party structure ensures that dual role members can only reach positions of limited authority (interview 13, online, May 4, 2024).

While “each parish of Caracas chooses a spokesperson from a commune via a popular election to be a dual role representative inside the PSUV, the regional part of the party continues to be managed by the same people, people in the role for more than 8 years who do not give way to other colleagues who have a different vision” (interview 13, online, May 4, 2024). There is a structural blockage in the party to ensure positions of actual weight or decision-making authority are filled by party-leadership loyalists, while a veneer of internal party democracy exists as locally selected commune members are invited into PSUV discussions.

These linkages are underpinned by coercive tactics including: a) legal controls; b) clientelism and manipulation of resource delivery; c) parallelism and co-optation; and d) fear and repression. Legal registration of comunas and consejos was mentioned by multiple interviewees as a control mechanism, whereby only popular organizations considered loyal to the PSUV are granted legal status — and access to state resources. Dual-role party-organization members are manipulated by senior party figures who demand “that because we (local activists) have participated in popular organizing, we have to get all of the local spokespeople to be members of the party, and to avoid any conflict” (interview 12, online, April 19, 2024). We “have to organize people to join marches, and if you do not get people to march, you will not be taken into account when it comes to receiving any resources” (interview 13, online, May 4, 2024).

The dire economic situation facing Venezuelans is manipulated by the PSUV leadership to maintain social control, perhaps most notoriously via control over deliveries of subsidized food boxes via Comites Local de Abastecimiento y Producción Local (Committees for Supply and Production, CLAPs). The CLAPs originated in April 2016 as partnerships between grassroots organizations and the government to provide food distribution that could overcome the issues of the black market for scarce foodstuffs. However, the program was heavily criticized by interviewees. Capturing such criticisms, Manuel Azuaje (interview, online, April 22, 2024) argues that the “party has eaten the comunas and consejos. This has been a political decision because when you insert a parallel organization like the CLAP, the consejo and comuna organizers become subordinate, they end up just working to solve welfare issues.”

Other PSUV-linked structures such as the Unidades de Batalla Bolívar Chávez (Bolívar Chávez Battle Units, UBCH) have a similar impact, creating parallel spaces in the community that subordinate the consejos and comunas because they are often filled by the same people as the UBCHs (interviews with multiple comuna and consejo organizers). The party-linked UBCHs receive orders from above to organize people to vote, impeding the possibility that consejos or comunas can act as spaces of critical political debate and organizing.

Carlos Oliveros (interview, online, April 23, 2024) rejects the notion that the CLAPs were established to intentionally subordinate pre-existing popular organizations, but does accept they have displaced popular leaderships in local settings. He suggests the “CLAPs were created as a response to an emergency, to help food distribution without having to deal with the participatory democracy of a consejo because it was an emergency.” Ramón Marcano (interview, online, April 18, 2024) suggests that the CLAPs, rather than weakening popular organizing, actually helped to re-organize people, because “popular power had been very disorganized. There was a lot of apathy. One of the most successful things the President did was to launch the CLAPs, because it allowed for reorganizing and to take control of distribution.”

However, many interviewees suggest that there is little scope for any popular critique of the party. The “party decide who gets to have the little privileges of delivering the food, and this then allows for control over the local consejos … So there is a dynamic today where the consejos are 100% controlled by the PSUV” (Miguel Denis, interview, online, April 25, 2024). Félix Velásquez (interview, April 22, 2024) shares such a view, arguing that “control is maintained by the party only giving resources to who it decides to, and in that way the party can impose its political cadres who take control of the local popular organizations.” In these scenarios, “little leaders, intermediaries between the party and community emerge … Those who are given positions of privilege by the party gain strength … They are the ones with the contact to whatever ministry delivers the goods, and they control who goes on the list to get things or not” (Miguel Denis, interview, online, April 25, 2024).

María Alejandra Díaz (interview, online, April 19, 2024) argues that in addition to problems of parallelism, clientelism, legal controls and co-optation that prevent autonomous popular organization, PSUV leaders use fear and repression to ensure there is no criticism. The “government has actively sought to co-opt some historical social movements — collectives — that are used as the armed arm of the government. When you try to organize an event … For example, we wanted to analyze the Anti-Blockade Law, those groups come, take photos of you. They intimidate popular organizations.” A May Day 2024 march calling for decent working conditions organized by workers and left-wing groups was attacked by a group of motorcyclists associated with the government. In the aftermath, critical leftist organizers Rafael Uzcátegui and Luis Zapata were threatened on state television by deputy Carlos Pacheco who requested criminal investigations into the role of “incitement to violence” and “conspiracy” (Aporrea), sending a clear message to anybody thinking of questioning the left-wing position of the PSUV.

In conjunction with physical attacks, María Alejandra Díaz (interview, online, April 19, 2024) outlines how legal threats are used to stifle popular organizing, stating that “fear is working. Until 2022 there were some demonstrations by teachers, professors demanding rights. They selectively went and looked for the ringleaders of these protests and charged them under the Law Against Hatred of 2017.” Díaz continues, stating that “these people are still in prison. It is difficult to organize when people are afraid. And now with the planned law against fascism, fear is growing because you can be jailed for 15 years.” The proposed anti-fascist legislation was discussed in the National Assembly in April 2024, with vice-president Delcy Rodríguez claiming the law would keep social order and confront fascist aggression, while referring back to violent protests in 2014 and 2017 led by the extreme right of the Venezuelan opposition.

The connections between the PSUV and popular organizations in a scenario of serious economic crisis have contributed to both the collapse and manipulation of popular power. Orders from above to dual-role members; the lack of formal spaces for criticism; manipulation through legal controls and access to resources; parallelism; cooptation and clientelistic relations between the party and the bases; as well as fear and repression, have prevented the construction of popular power. There is clear evidence of manipulation of popular power with widespread passive obedience to the PSUV (although, as discussed below, there is some resistance). Clientelistic loyalty has limited popular power, understood as the ability to challenge the leadership of the party-state.

Challenges to revitalizing popular power and resistance building

Revitalizing popular power requires challenging scenarios of collapse and manipulation, before engaging in resistance. Resistance is conceptualized as involving a rejection of the party leadership’s deviation from the founding promises of the Chavista project to be radically democratic and follow a path away from neoliberal development. However, resistance to clientelism and vertical manipulation of popular organizations, as well as the promotion of a popular counterpower to Maduro’s bureaucratic-authoritarian bloc has been weak and remains embryonic, while the PSUV/state’s responses to any criticism have further fragmented efforts to build popular counterpower.

Internal critique of PSUV

When comunas and consejos are invited to internal PSUV spaces of discussion, they do not do so as autonomous actors capable of influencing the party leadership. Some community organizers refute this and suggest that there is room to operate with connections to the Maduro bloc. For example, in informal discussions in June 2024, a spokesperson for Unión Comunera (a grouping of over 50 comunas) suggested that while they retained backing for Maduro, they could indeed critique him.

However, according to a Red Nacional de Comuneras y Comuneros (RNC) spokesperson (interview 14, online, June 1, 2024), the main Caracas leaders of the “Unión Comunera do not challenge the PSUV. In fact, they promote and participate in electoral events sponsored by Maduro, along with all the other false opposition parties financed by Maduro and the other co-opted movements.” Ulises Castro (interview, online, May 24, 2024) says that “in the Unión Comunera there is no homogeneity. Some sectors are very close to the party, but there are others who demand autonomy and have confronted the party.” While there may not be a homogeneous position within the Unión Comunera as to how to relate to or challenge the party, this indicates weak associational and collective power. That is, such homogeneity is not a strength, but a weakness.

Furthermore, even when there may be high-ranking party members who support the construction of popular power, they are a minority and have no capacity to challenge Maduro’s dominant bloc. The comuna movement “has no counterpower, they have no weight within the government” (Manuel Azuaje, interview, online, April 22, 2024). A peasant and communal organizer told us, “I spoke with the former governor and vice president Aristóbulo Iztúriz … He told us that when he was Minister of Comunas, Maduro paralyzed him and told him not to be too quick in responding to our demands” (interview 15, online, April 23, 2024). The peasant organizer also spoke of his meetings with the former high ranking PSUV official, Elías Jaua, stating how he criticized the nature of the relationship between the PSUV and the comunas within the party, but that he was ostracized for doing so. The problem is that while Jaua may have sought to lead a critical current within the PSUV, and while some popular organizations may have supported him strategically, Maduro did not feel any pressure to respond to Jaua or those organizations that supported him. Maduro’s ease in sidelining critical voices inside the party is partly related to the weak mobilization capacity of popular organizations.

External contestatory mobilization

Beyond encouraging a widespread disengagement from participation, the controlled relationship between party and popular organizations has caused fissures within and between organizations, culminating in a weakened civil society sphere as the density and unity of organizations has been damaged (particularly since the death of Chávez). With “so many people dependent on the PSUV and positions granted in the state” there are many people who are not willing to join more critical voices from their consejo or comuna (Félix Velásquez, interview, online, April 22, 2024). In a polarized scenario in which sectors of the opposition have openly called for greater US sanctions and even military interventions, those who raise a critical voice “are considered traitors” by the party (JM Rodríguez, interview, online, May 22, 2024) and by those popular organizers who have been absorbed by the party (Yesmel, interview, online, April 18, 2024).

Collective power building has remained moderate. The connections between the consejos/comunas and the PSUV leadership limit the ability to build consejo-consejo or comuna-comuna links (interview 12, online, April 19, 2024). Society “remains fragmented, there are no mechanisms of interrelation between the popular organizations themselves, so there is a weak capacity to articulate a social force and become a counterweight to the abuses of the executive” (Carlos Molina, interview, online, April 22, 2024). Manuel Azuaje (interview, online, April 22, 2024) maintains that although there are “4 or 5 really important comunas —- El Maizal, El Panal, Che Guevara, things in the El 23 de Enero neighborhood … At the end of the day, these few comunas represent around 0.01% of the population ... There are no real connections and debates from these comunas that reach the majority of the population. And Maduro, consequently, does not need to deal with them.”

There are examples of weak low-density protest actions. For example, once a week, 20-30 people protest and demand the release of workers imprisoned on trumped up corruption charges. Another example of popular pushback was the rejection by members of consejos and comunas in San Juan (Caracas) regarding the PSUV’s decision to select who would participate in Hugo Chávez Brigades.2 However, popular organizers in San Juan took “three buses to the PSUV headquarters in San Bernadino. They demanded the PSUV mayor respect the popular assembly and not impose structures on the parish that were full of people who were not local activists. They took over the PSUV headquarters with Diosdado Caballo and the mayor inside until 3 in the morning” (interview 12, online, April 19, 2024).

Such sporadic protest actions focused on narrow issues with low levels of participation indicate growing discontent with the PSUV, but also highlight the weak power of protest mobilization that currently exists. What is required “is that we make a true community explosion in which everyone participates. We need to gain heat in the streets so that they listen to us” (interview 13, online, May 4, 2024). Without internal avenues for popular resistance and with a weak contestatory mobilization capacity, sectors of the left have tried to challenge the PSUV electorally.

Challenger parties to the left of the PSUV

Some left-wing parties have taken initiatives to challenge the PSUV. However, a combination of fragmented connections throughout the Venezuelan left; the absorption/adhesion of possible PSUV sympathizers; the lack of an existing national network of autonomous popular organizations upon which to launch a party; PSUV interference inside challenger parties; legal impediments; and threats (of legal action, imprisonment and physical violence) have limited the ability of small critical parties to offer an alternative between the polarized options of Maduro's PSUV and the traditional right-wing opposition.

The “PSUV via the CNE (National Electoral Council) has eliminated all party cards linked to anything that could challenge it from the left. People from the PSUV called us, they said … ‘Look, you can keep your card, but only if you support Nicolás (Maduro)’ (Félix Velásquez, interview, online, April 22, 2024). It was suggested that María Alejandra Díaz could run in the 2024 presidential elections, but, as Díaz herself described to us (interview, online, April 19, 2024), the leaders of the PSUV

Enacted a series of practices that prevent alternative electoral options. They said we had to register between March 11 and 13, just three days. But then they responded saying they couldn’t validate the application because no signatures were submitted along with the application, a requirement made up out of thin air. And they required you to collect signatures from 5% of the electoral roll, 1.3 million signatures. But the signatures could not be collected in any format, the CNE itself has to give you the form. Which they never gave us.

Parties that resist and continue to try to offer an electoral alternative have faced interference in their leadership structures as the PSUV — via TSJ, CNE, Comptroller General — has placed its own loyalists inside the party and legally recognized them as registered parties, while refusing to register the “disloyal” critical factions. Such parallelism even occurred inside the Communist Party of Venezuela.

Underpinning the PSUV tactics to impede registration and participation of a leftist party capable of challenging it across the Venezuelan territory was the lack of a unified and powerful social movement network upon which to launch such a challenger party. While there are dedicated radical party organizers attempting to overcome the PSUV’s variety of tactics to block its participation/survival, lacking organic connections to a powerful and coherent popular movement that can simultaneously pressure the PSUV from the streets, the outlook for the left is catastrophic.

Defensive autonomy and strategic quiescence

The power of the PSUV and its variety of tactics to control and impede resistance has fostered a feeling in some popular organizations and comunas that the best option for survival is to withdraw completely from the institutional sphere. While for some John Holloway’s (2002) tactic of “changing the world without taking power” was always the only path, others who had previously believed that a radically democratic party could act as a vehicle for change have withdrawn from such positions (interviews with multiple organizers and activists). While such a stance is entirely understandable; the result is that potential popular counterpower to challenge the PSUV is further debilitated.

For others, strategic quiescence is the best option. That is, numerous interviewees explained to us how many people who participate in their comuna or consejo, who consider themselves Chavistas, do have major criticisms of the government and the PSUV leadership. However, according to our interviewees, the nature of the opposition and the polarised scenario, in conjunction with a deep loyalty to a party and project that in the past delivered enormous benefits, voice, and a sense of representation to popular sectors means there is a reluctance to openly critique the PSUV. However, in terms of revitalising popular power and resisting the authoritarian and neoliberal turn, strategic quiescence suits the PSUV leadership.

Maduro fuels these positions and uses polarizing rhetoric to silence popular criticism. “Nicolás said in our meeting that we are in a constant war, not only with opposition agents, but from within” (interview 13, online, May 4, 2024). For many, this position is the only way to defend the achievements of the Chavista project. Capturing such sentiment, one interviewee told us “I believe that many of the so-called critical Chavista parties have been infiltrated. We are all either Chavistas or we are not. This position of ‘I am a Chavista, but a Chavista-no-Madurista’ … No. You are either with us or not. Anybody who threatens the stability and interest of el pueblo [the people] must be sanctioned” (interview 11, online, April 19, 2024). Maduro’s campaign to present leftist criticism as equivalent to right-wing opposition has successfully sowed division, further weakening efforts to build popular counterpower.

Weak popular counterpower and PSUV control over resistance efforts

Counterpower and popular resistance — debilitated by controlled-clientelist ties, weak contestatory power, fractured electoral alternatives, a retreat toward autonomous positions and strategic quiescence — allow the PSUV to control and dilute any critique that does emerge. As discussed above, the party co-opts, ignores, marginalizes, buys off, or represses resistance efforts, which in turn feeds back into the tactics and strength of popular power, further diluting resistance efforts (see diagram 2).

Recognising that discontent exists among its traditional electorate, and seeking to shore up support before the July presidential elections, the PSUV called for a national popular consultation on April 21, 2024. Each officially registered commune was called upon to mobilise people in their localities — whether active in the commune or not — to vote for one of seven projects they felt was most important for their community. The government would then give $10,000 to each commune to carry out projects relating to the supply of water, gas, electricity and roofing.

Anecdotal evidence from interviewees suggest participation levels were relatively high. While the national consultation appears a positive step, for some interviewees the process was simply an electoral stunt. A communal activist highlighted “while $10,000 might seem like a lot, when a comuna has 578 members, maybe 15 consejo comunales, it is hard to say that the money is really going to cover much” (interview 12, online, April 19, 2024). While it can be debated whether the national popular consultation was an effort to achieve true participatory democracy or whether it was a vote-buying exercise, the recently launched Movimiento Futuro (Future Movement) represents a clearer effort to control popular dissent.

The PSUV recently launched the Movimiento Futuro. This space was supposedly created to attract those Chavistas and social movement organizers who do not want to vote for the opposition or the governing party. A pro-Maduro militant from the PSUV and local organizer told us that the Movimiento Futuro is going to be a space for “committed people who have been working for a long time from the base, our people. People from the movements who have felt excluded by some PSUV practices. The President has invited them to this space where self-criticism can be expressed” (interview 11, online, April 19, 2024).

Ulises Castro (interview, online, May 24, 2024) says “that the discontent of comuna leaders, for example, those who do not want to vote for the PSUV … Some are assuming militancy in Movimiento Futuro. It’s good that there is discontent within Chavismo regarding voting for the PSUV, and now they have an alternative … There are actors who see in the Movimiento Futuro a possibility of building a different model of party that overcomes the distortions of the PSUV.”

However, it is worth emphasizing that the Movimiento Futuro is promoted by Héctor Rodríguez, current governor of the state of Miranda and a senior official of the PSUV. As a current PSUV member and activist summarizes, “Maduro knows that so many people do not want to vote for him, people from the comunas. So, the PSUV itself is creating another party with some comrades from the comunas” in order to make it seem like there is a space for critical activists to vote and participate in something. (interview 13, online, May 4, 2024).

Facing simmering discontent, and having controlled all other avenues of expressing critique of the PSUV — internally, via contestatory mobilizations, or via alternative electoral options — the final tactic by the Maduro clique is to create a dummy party/movement that presents itself as being an avenue for critical Chavistas to counter the authoritarian-neoliberal PSUV project, while in fact, the Movimiento Futuro will simply absorb, dilute, and disperse any potential counterpower that could challenge the party leadership.

Despite all the challenges, embryonic efforts to revitalize popular power persist. Movements, organizations and parties that sought to challenge Maduro’s PSUV, and that were crushed by the party-state, have not completely disappeared, but they are weakened. For example, after a series of assemblies throughout 2023-24, there are plans to launch a new movement that links comunas and producers (interview 14, online, June 1, 2024).

Ulises Castro (interview, online, May 24, 2024) says that “we have been in a regrouping process for two years. We have built a muscle of associations in networks of producers with proposals for agri-food development, with national reach.” The hope is that by building associational and collective power, comuna members will have “more possibilities to sit down and negotiate things with the state, to discuss in a horizontal relationship … No longer as a weak, disintegrated community that is asking for resources to satisfy very specific needs.” However, it remains to be seen whether such processes can help trigger a broader revitalization of people power.

Final observations

The development of co-opted connections between the party and the bases is at the root of the collapse and manipulation scenarios confronting popular power in Venezuela, while these same controlled connections have impeded a revitalization of popular power and resistance to the authoritarian-neoliberal turn of the Chavista project led by the PSUV. “Creative tensions” between organized popular sectors and an office-seeking leftist party became “creative destruction” as PSUV leaders utilized an array of tactics to manipulate and control dissent. While there is widespread discontent in Venezuela, the collapse and manipulation scenarios remain sufficiently embedded that critical left organisers and parties have faced extraordinary difficulties in fostering resistance.

It remains to be seen what happens if and when the PSUV loses office and control over resources it utilises to lubricate a social peace. Indeed, while popular power and organization are at a low ebb currently, the seeds of a coherent popular movement capable of shaping Venezuelan politics and society are in place, albeit in a dormant state. Consejos and comunas could generate a movement at the national level if they break from the tutelary control of the PSUV.

Looking ahead, unlike the ad hoc eruptions of discontent regarding the neoliberal responses to economic crises in the 1980s and ’90s that preceded and shaped Chávez’ emergence and presidencies, one may be hopeful that the consejos and comunas can be reclaimed and utilised as springboards to launching mass popular protests — against a possible right-wing government or even against an authoritarian PSUV government. Indeed, if such popular organizing can continue, it is possible that a new party emerges with organic linkages to well-organized popular sectors, inverting the process that witnessed Chávez act as a binding figure for disorganised popular sectors.

Beyond conceptualizing what an organic connection might look like (see Anria et al. 2022 discussed above), the key challenge is to try and grasp why connections take organic/controlled forms. One of the core lessons from the Venezuelan case is the risk posed by weak collective power and movement organizations in the antecedent phase that precedes the election to office of a leftist leader/party.

In the absence of a powerful movement scene, Chávez emerged as a type of vanguardist leader who utilised state resources to help foster popular sector organizing. Ulises Castro (interview, online, May 24, 2024) notes the initial efforts during Chávez's two presidential terms “were aimed at delivering government-funded missions, which have benefited the people. But not under the logic of building an autonomous popular movement. Autonomy involves building strength and muscles. If an organization or social movement does not have strength and muscle, it will be defeated by the power of the state, by the power of the parties.”

As analyzed above, over time, the links between the PSUV and popular organizations became increasingly clientelistic and co-opted. Building a powerful movement scene before launching a party that then emerges with organic connections to popular organizations — organizations that are themselves founded upon strong internal democracy to ensure that any dual members are not absorbed by the party but rather remain tethered to grassroots organizations — will be of critical importance.

As the Venezuelan case indicates, where controlled connections are forged, levels of associational and collective power are likely to be reduced, meaning that contestatory mobilization capacity will be weakened. In such scenarios, party elites may ignore or repress critique from street protests that are low density and sporadic. Once inorganic connections become embedded, they are tough to break — as the struggles of critical Chavistas in popular organizations and in small left-wing parties attest.

Future lines of investigation may look to refine the framework and conceptualizations advanced here to examine if and why popular power collapses, becomes manipulated, or can become a resistance-counterpower. It would be useful to compare other cases such as the Bolivian Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement Towards Socialism, MAS), Spain’s Podemos, and Greece’s Syriza, where outsider-left parties emerged utilizing an anti-neoliberal rhetoric while claiming to respond to popular demands for a deepened form of participation in a new type of movementist party. Learning the lessons — good and bad — from these experiments is critical.

While changing the world without taking power and wholesale autonomy from party and state institutions may offer one pathway for progressive forces to survive, such a position offers little response to the major crises — economic, social and climate — facing society today. Failure to confront this reality will only further cede space to far-right forces who have captured the contemporary moment of deep democratic discontent. Despite all the inherent tensions, thinking on how to build and maintain organic connections between movements and parties remains the central task of progressive thinkers and activists if we are to offer pathways out of the current democratic quagmire.

References

Anria, Santiago, 2019 When Movements Become Parties: The Bolivian MAS in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Anria, Santiago, Pérez Betancur, Verónica, Piñeiro Rodríguez, Rafael and Rosenblatt, Fernando, 2022 “Agents of representation: the organic connection between society and leftist parties in Bolivia and Uruguay.” Politics and Society 50(3): 384-412.

Aporrea, 2024 “Solidaridad con Rafael Uzcátegui y Luis Zapata, ante amenaza pública de criminalización.” May 10. https://www.aporrea.org/trabajadores/n392776.html (accessed on May 10).

Azzellini, Dario, 2018 Communes and Workers’ Control in Venezuela: Building 21st Century Socialism from Below. Chicago: Haymarket Books

Bracho, Yoletty, 2022 “La revolución como coyuntura: militantismo excepcional y trabajo ‘en el Estado’ de las organizaciones populares en el contexto de los gobiernos chavistas del siglo XXI.” Espacio Abierto 31(2): 90-102.

Brown, John, 2020 “Party-base linkages and contestatory mobilization in Bolivia’s El Alto: subduing the Ciudad Rebelde.” Latin American Perspectives 47(4): 40-57.

— 2022 Deepening Democracy in Post-neoliberal Bolivia and Venezuela: Advances and Setbacks. Abingdon/New York: Routledge.

— 2023 “Crisis de la democracia de mercado y las respuestas populistas: el caso de Evo Morales de Bolivia,” in Pozzi, Pablo, Munck, Ronaldo and Mastrángelo, Mariana (eds.) Populismo: Una Perspectiva Latinoamericana. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

— 2024 “Los vínculos entre el partido y la base, la movilización contestataria y las ‘tensiones creativas’ en Bolivia,” in Steve Ellner, Ronaldo Munck and Kyla Sankey (eds.) Gobiernos Progresistas y Movimientos Sociales: Resistencia, Convergencia y “Tensiones Creativas.” Buenos Aires: CLACSO

Cameron, Maxwell, Hershberg, Eric and Sharpe, Kenneth, 2012 New Institutions for Participatory Democracy in Latin America: Voice and Consequence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cannon, Barry, 2009 Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution: Populism and Democracy in a Globalised Age. Manchester/New York: Manchester University Press.

Ciccariello-Maher, George, 2013 We Created Chávez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution. Durham: Duke University Press.

— 2013a “Constituent moments, constitutional processes: social movements and the new Latin American left.” Latin American Perspectives 40 (3): 126–145.

— 2016 Building the Commune: Radical Democracy in Venezuela. New York: Verso Books.

Ellner, Steve, Munck, Ronaldo and Sankey, Kyla (eds.), 2022 Progressive Governments and Social Movements: Resistance, Convergence and ‘Creative Tensions’. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Fernandes, Sujatha, 2010 Who Can Stop the Drums?: Urban Social Movements in Chávez’s Venezuela. Durham: Duke University Press.

García-Guadilla, Maríá Pilar, 2020 “Venezuela 2020: autoritarismo político y pragmatismo económico.” Nueva Sociedad, (287): 108-120.

García-Guadilla, Maríá Pilar and Castro, Ulises, 2022 “Will popular power survive? popular power was a cornerstone of the Bolivarian Revolution. Facing co-optation, crisis, and decline, its future remains in question.” NACLA Report on the Americas 54(1): 90-95.

García-Guadilla, Maríá Pilar, Torrealba, Carlos and Duno-Gottberg, Luis, 2022 “Experiencias de movilización y resistencia de las organizaciones, movimientos sociales y colectivos de la Revolución Bolivariana.” Espacio Abierto 31(2): 10-21.

Gaudichaud, Franck, Modonesi, Massimo and Webber, Jeffrey, 2022 The Impasse of the Latin American Left. Durham: Duke University Press.

Giusti-Rodriguez, Mariana, 2023 “From social networks to political parties: indigenous party-building in Bolivia. American Political Science Review First View: 1-21.

Hetland, Gabriel, 2023 Democracy on the Ground: Local Politics in Latin America’s Left Turn. New York: Columbia University Press.

Holloway, John, 2002 Change the World without Taking Power. London: Pluto Press.

Levitsky, Steven, Loxton, James, Van Dyck, Brandon and Domínguez Jorge (eds.), 2016 Challenges of Party-building in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Ecosocialismo, 2024 “Gran Misión Igualdad y Justicia Social Hugo Chávez” http://www.minec.gob.ve/gran-mision-igualdad-y-justicia-social-hugo-chavez-es-un-homenaje-al-legado-del-comandante/ (accessed May 21)

Munck, Ronaldo, Mastrángelo, Mariana and Pozzi, Pablo (eds.), 2023 Populism: Latin American Perspectives. Newcastle: Agenda.

Roberts, Kenneth, 2014 Changing Course: Party Systems in Latin America’s Neoliberal Era. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rosales, Antulio and Jiménez, Maryhen, 2021 “Venezuela: autocratic consolidation and splintered economic liberalization.” Revista de Ciencia Política 41(2): 425-447.

Silva, Eduardo, 2009 Challenging Neoliberalism in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Silva, Eduardo and Rossi, Federico (eds.), 2018 Reshaping the Political Arena in Latin America: From Resisting Neoliberalism to the Second Incorporation. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Torrealba, Carlos, 2022 “Entre tutelaje y emancipación: procesos de institucionalización y repertorios de resistencia comunal en Venezuela.” Espacio Abierto 31(2): 22-38.

Velasco, Alejandro, 2015 Barrio Rising: Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. Oakland: University of California Press.

- 1

Roughly translates as "Those people are old hens, they neither lay nor leave their eggs."

- 2

The Brigades are conceived by the party as meeting points for “all the communities in the country, with the spokespersons of the consejo, the Somos Venezuela Movement, community and street leaders, teachers, health committees, the Bolivarian National Militia, social movements and community groups and the Francisco de Miranda Front” (Ministry of Popular Power for Ecosocialism). The Brigades are supposed to help organize communities to implement plans related to “equality and social justice” as part of the new Hugo Chávez Great Mission Equality and Social Justice.