Sam Wainwright (Socialist Alliance, Australia): Impressions of the CPIML Liberation 11th Party Congress

First published at CPI(ML) Liberation.

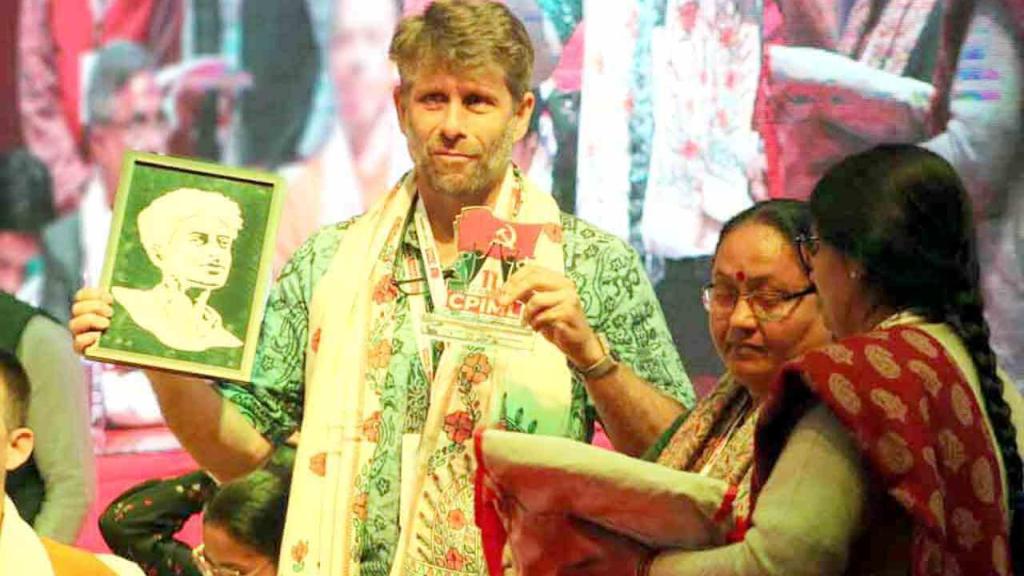

Our organisations have had relations for over two decades now and I have always been impressed by the presentations by CPI(ML) Liberation comrades when they have visited Australia. However, attending the 11th Party Congress in Patna and the time I spent with comrades in West Bengal beforehand was my first opportunity to see the party in action.

I came away very much convinced that the CPI(ML) has a critical role to play in the struggle of the Indian masses. Furthermore, it has much to contribute to vital discussions among the international left.

This observation flows from the fact that the CPI(ML) has a mass base in real struggle, a dynamic and non-dogmatic grasp of Marxism, a democratic internal life and sophisticated tactics in the face of some very big challenges. Taken together, these are no guarantee of further success, but they are certainly among its preconditions.

In identifying some of the important questions about which I think that the CPI(ML) has important experience and ideas to contribute, I am not seeking to give advice. My organisation has always emphasised the importance of respect and non-interference in our relations with parties in other countries, all the more so because there's a long and unhelpful tradition of revolutionaries in the Global North trying to tell comrades in the Global South what to do. A reflection of imperialist thinking within the left perhaps, and something we do our best to avoid.

Secondly, while we have real influence in some movements and campaign initiatives, we are a small group oftentimes restricted to propaganda rather than being able to exert real influence in class struggle. Consequently we are cautious about pretending to have great insights about the course of struggle in our own country, much less other ones.

Not only is Australia a wealthy imperialist country, but compared to both the US and Europe, it escaped the worst of the Global Financial Crisis. This fact, combined with the country’s particular history as a colonial-settler state based on Indigenous dispossession, makes for relatively conservative politics, a low level of struggle and reinforces pro-imperialist consciousness among the working class. Of course Australian capitalism still has its own intense contradictions and these may yet explode in ways we can’t foresee.

With those caveats in mind, what follows are some areas where I believe the CPI(ML) can greatly enrich discussion in the international left. It’s not intended to be an exhaustive list and I’m sure there is more that could be added.

The very clear and deliberate characterisation by the CPI(ML) of the Modi government and the broader RSS project as fascist helps open up important discussion about what fascism looks like today. While it’s important to retain a rigorous definition of fascism that doesn’t use the term lightly, we also have to move beyond anchoring this understanding in the European experience in the first half of the 20th century.

In both unequivocally condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine while conceding nothing to the strategic aims of Western imperialism and acknowledging its still decisive role in world capitalism, the CPI(ML) has adopted a similar position to ours. Western imperialism makes much of the authoritarianism of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping to bolster its claim to be defending democracy and a mythical “rules based order”. The courting of Modi by the Anglo-imperialist bloc and the twentieth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq are just two things that make a mockery of this nonsense.

Nevertheless, the balance of forces in the world is changing. Traditionally we would have described countries who are more industrialised than most of the Global South, but still way behind the West, as “semi-peripheral”. However this has usually assumed a subordinate relationship to a major Western imperialist centre, such as that between Mexico and the US.

Given the independence of Russia and China from Western imperialism, and indeed their confrontation with it, we almost certainly need a better language for describing them and their relationship to the Global South. A whole series of questions are posed:

Can a Eurasian capitalist bloc including Russia, China, Iran and others endure as a rival to Western imperialism? If so, what are the implications for the struggle for socialism? What are the limits of the Chinese development model, and to what extent can it be followed by other countries of the Global South?

While India’s level of industrialisation might still be well behind economies like China and Russia, let alone the Global North, it is nevertheless a significant regional power. The Anglo-imperialist bloc was understandably keen to draw India into the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in its push to “contain” China.

However, like a number of governments in the Global South, rather than rush to join the West’s attempts to isolate Russia, the Indian government has responded both with caution and sought to play the situation to the advantage of Indian capitalists. Does this signal a more profound shift in the alignment of Indian capitalism, and if so, what meaning does that have for socialists?

Australia is a thoroughly urbanised society with no peasant legacy whatsoever, and where agricultural production has always been almost entirely for the market and not consumption by the producer. In contrast, it’s clear that while the percentage of the population in India that lives in the cities is continuing to climb, urbanisation is not following the path seen in the Global North.

A large section of the population live between city and country, and retaining connection to land remains a vital form of social and material support for many urban dwellers. A similar pattern is developing in Australia’s near neighbours like Indonesia and the Philippines, and comparing these experiences with the Indian one could be valuable for Indian comrades.

The lived reality and contemporary function of caste is something of a mystery for comrades outside India. The CPI(ML)’s understanding of the way in which Indian capitalism has not gradually undermined caste but has instead lent upon it and in fact reinforced it is fascinating and merits being summarised in an accessible form for a wider audience.

As an outsider it was particularly interesting to see how the CPI(ML) congress tackled head-on the relationship between the oppression of women in society at large and the need to increase women’s participation in the party itself. While women constituted only 17.5% of congress delegates, it was encouraging to see the much higher representation of women among the leading younger comrades and those that spoke from the floor around the Party Organisation Report. It will be interesting to learn more about the work of the Gender Justice and Sensitisation Commission.

Finally, what the CPI(ML)’s work and experience most has to offer the left outside India is inspiration. From the patient and determined base building in Bihar that has seen the party burst on to the national stage as the most dynamic communist party across the Hindi Belt, through to the organisation of sanitation workers in Karnataka, and more, the party has so many stories to tell.

The courage and success of comrades in one country has always been invaluable in galvanising struggle in another. We look forward to continuing our collaboration with the CPI(ML), learning from your experiences and offering our solidarity as best we can.