Spanish state: candidate preselection turmoil as ‘existential’ election looms

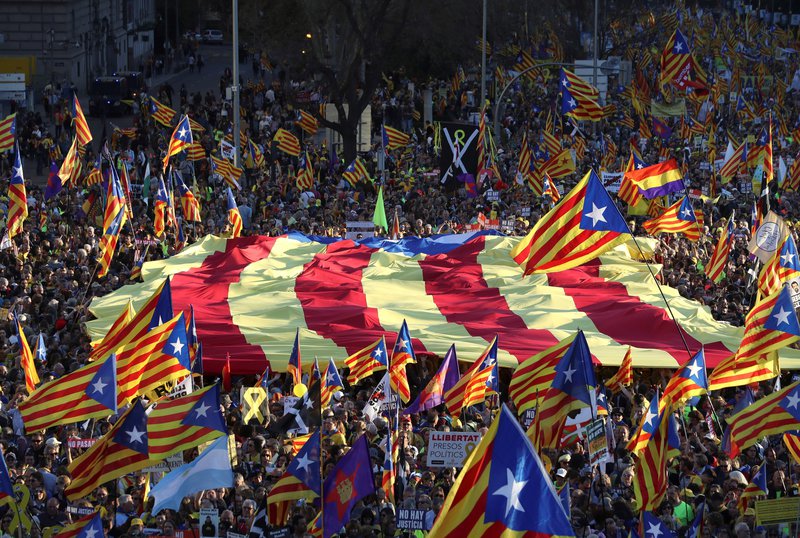

This shared judgment of Spain’s "parties of government" would only have been heightened by the resounding success of the March 16 Madrid demonstration "Self-Determination is not a Crime: Democracy is Deciding". The rally, organised by the Catalan National Assembly, Òmnium Cultural and the platform Women and Men of Madrid for the Right to Decide, brought into the capital up to 120,000 supporters of the right to self-determination of the nations of the Spanish state. The size and spirit of the demonstration marked an important step ahead down the long road to a democratic alternative to Spanish state unionism.

Its enemies certainly felt challenged. PP deputy organisational secretary Javier Maroto immediately attacked PSOE prime minister Pedro Sánchez and Madrid mayor Manuela Carmena for allowing the demonstration, tweeting that "with Pablo Casado that will never happen again". In reply, Sánchez stressed the PSOE’s even-handed adherence to Spanish state constitutionality: "The democracy that guarantees the freedom of protest is the same one that judges the [Catalan] politicians who break the constitutional rules and legality … Under a Socialist government the independence of Catalonia will not occur."

Just to prove the point, two days earlier, the Sánchez government had lodged an appeal with the Supreme Court against the Catalan parliament’s establishment of a commission to investigate the Spanish monarchy.

Candidates imposed

Given the struggle for hegemony within the right between the PP and the "liberal" Citizens—intensified by the rise of the neo-Francoist Vox—preparations for this general election have been exceptionally frenzied and brutal: sacred principles and immovable MPs alike are being dumped in the war for votes.

The most ruthless preselection process has been taking place in the PP. Scored by Vox for the «cowardly» performance of the former government of prime minister Mariano Rajoy in failing to crush the October 2017 Catalan referendum, Casado has purged nearly all "Marianists" from his party’s lists: only two of Rajoy’s ministry will repeat on April 28 along with only 10 of the PP’s lead candidates in Spain’s 50 provinces and two Moroccan enclaves (Ceuta and Melilla).

Replacing them come an ultra-conservative gang imposed by Casado in accordance with the old saying “Madrid blows the whistle and everyone falls into line”. They make up a foul mix of unionist "intellectuals", assassins for Casado within the PP machine and individuals whose chief claim to a Congress seat is having had a relative murdered by the military-terrorist Basque Homeland and Freedom or a serial killer. Many are associated with previous prime minister José María Aznar and his neo-liberal, Spanish-patriotic think tank, the Foundation for Social Analysis and Studies (FAES).

The PP’s "star candidate" is former MP Cayetana Álvarez de Toledo (the Marchioness of Casa Fuerte), columnist for the Vox-sympathising daily El Mundo and notorious for a 2015 article criticising the Rajoy government for not squelching the November 9, 2014 Catalan "participatory process". Álvarez de Toledo is to be the PP’s lead candidate in the Barcelona district, where she will be up against Citizens’ "star" Ines Arrimades, formerly opposition leader in the Catalan parliament.

Voters of the right will have their work cut out deciding which of the two would be their staunchest warrior. Arrimadas has solid credentials based on 15 months of rancid abuse of Catalan president Quim Torra and waving Spanish flags in the Catalan parliament, but Álvarez de Toledo brings her own impressive asset to the fight—she speaks not a word of Catalan. As she told a March 16 Madrid meeting:

The more they say that ‘Cayetana is not from here, she doesn't speak Catalan, she has no right to represent us’, the more my candidature makes sense ... The nationalist project in Catalonia can be summed up in the single objective of turning compatriots into foreigners.

For the PP, however, preselection of its Cayetanas so as to staunch desertions to Vox—which calls for all nationalist and Marxist parties to be outlawed—comes at a price, especially in those regions where the party is in tension between one˗eyed Spanish centralists and social conservatives more reflective of local sentiment.

Besides Catalonia, where the locals preferred former PP health minister Dolors Montserrat, Casado has imposed his people in districts with strong regional identification, like the Balearic Islands, the Valencian Country and the Basque province of Guipuzkoa. The only important region where he has had to make any concession to local PP “moderates” is Galicia, homeland of Rajoy and stronghold of local premier Alberto Núñez Feijóo.

The PP’s job is made harder at this election by the rigged Spanish electoral system that was set up to favour two-party stability and which punishes all-Spanish parties winning less than 15% of the vote. It is based on 52 constituencies of unequal size, with the number of votes needed to win a seat varying between under 20,000 to over 100,000. The PP, now rating just over 20% in the polls, will have to compete with the PSOE for the last seat in as many as half of the electorates. The arrival of Vox, while potentially boosting the overall right vote in the big constituencies (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Seville), increases the chance of the PSOE carrying off the last position in these smaller, more rural, constituencies. To forestall this result Casado called on Vox not to stand in 25 electorates, a call that was of course rejected.

Principles dumped

Yet the landscape for the right is not just one of splits: in Navarra, conservative unity has been achieved between Citizens, the PP and the right-regionalist Union of the People of Navarra (UPN), who will run together under the banner “Navarra Adds Up”. Their goal is not only to secure a majority over left and nationalist forces in the general election, but to rid Navarra and its capital Iruñea (Pamplona) of their present administration, which are coalitions of the all-Spanish Podemos and United Left with Navarran and Basque regionalist and pro-independence forces, at the May 26 regional and local government elections.

The price of this unity of the right has been a tiny sacrifice of principle. Citizens has always demanded abolition of Navarra’s and the Basque Country’s unique power to raise taxes, meet local needs first and only afterwards transfer funds to Madrid. Citizen’s leader Albert Rivera, the most ardent champion of free markets and level playing fields in Spanish politics, used to call this arrangement a “dirty deal done with the nationalists in a dark room”.

Faced, however, with the prospect of driving back the “enemies of Spain” on the important Basque frontier, Citizens has just dropped its opposition to Navarra’s “jackpot prize” and made common cause with those once found guilty of “disloyalty to Spain”. In the words of general secretary José Manuel Villegas: “There’s a need to come together in defence of the Spanish essence of Navarra, of the Constitution in the entire territory of Spain and to achieve a constitutionalist government.”

Catalan abstention in Congress?

Matters are equally complicated in the camp of the right’s worst enemy, Catalan independentism. The April 28 election has dramatised its acutest dilemma: what role should pro-independence Catalan MPs play in the Spanish Congress?

Some believe they shouldn’t be there at all: the March 10 meeting of the Political Council of the People’s Unity List (CUP), voted by 37 to 20 with four abstentions not to stand for Congress on April 28. Spokesperson Carles Riera gave four reasons for the decision: the CUP’s priority is to grow at the local level, where the realisation of the Catalan Republic can advance most readily; in the struggle to break with the Spanish state the Catalan battlefront is more important than that of “Madrid”; there’s no hope of extracting concessions from any conceivable Spanish government or the main parties in Congress; and finally, from the perspective of self-determination for the entire Catalan Lands, standing in Catalonia alone sends a false message.

Two days later, CUP affiliate Poble Lliure (Free People), which had urged a vote in favour of a CUP candidacy, decided that it would stand its own ticket. It was joined in a coalition to be called the Republican Front by the Pirates, We Are Alternative (led by former Podemos Catalonia general secretary Albano-Dante Fachin) and the revolutionary independentist youth organisation The Forge. The decision provoked a lot of tension within the CUP, however was put under provisional control by Poble Lliure’s agreement that it not would run any of its officeholders in the CUP or local government as candidates for Congress

How will any Republican Front candidates elected to the Spanish Congress act? According to The Forge, it should not “yield a millimetre in the face of possible blackmail and it will be necessary to not give support to any organisation that does not give a commitment to defending the right to self-determination and the social rights of the Catalan people. This is a point of difference compared to other pro-independence candidacies which, in adopting a negotiating role, end up playing the game of the State.”

It remains to be seen how this line of abstaining on the formation of any conceivable Spanish government will work out in practice, particularly if Republican Front votes will determine whether Spain has a PSOE-led or right-wing government after April 28.

Similar tension haunts the mainstream parties of Catalan independentism, represented until now by the rival centre-left Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and centre-right Catalan European Democratic Party (PDECat).

The outgoing PDECat Congress caucus was the last outpost in Catalan institutional politics of the culture of horse trading with Spanish governments that characterised the former main party of Catalan conservatism, the Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (CDC). PDECat now disappears, to be replaced by Together for Catalonia (JxCat), the same platform (including PDECat) with which ex-president Carles Puigdemont won the December 21, 2017 Catalan elections.

JxCat was not Puigdemont’s preferred vehicle for April 28: committed to building a single coalition of all pro-independence parties, the former president, his successor Quim Torra and jailed Catalan National Assembly ex-president Jordi Sànchez launched National Call for the Republic (CNR) as an umbrella to promote unity within the entire pro-independence spectrum. However, when neither the CUP nor ERC showed any interest in joining the CNR, JxCat was left as the best brand name to hopefully broaden the support base of a PDECat that has been sinking further behind the ERC in the polls.

Candidate preselection for JxCat saw weeks of tense negotiations between the PDECat incumbents and the “Puigdemontists”, and ended in victory for the latter. Longstanding PDECat MPs like Carles Campuzano were dumped while Puigdemont supporters scored most of the winnable positions for the four Catalan provinces, behind political prisoner lead candidates Jordi Sànchez, Jordi Turull and Josep Rull.

With or without these prisoner MPs, the incoming JxCat Congress caucus seems set to follow a line of basically offering no support to any all-Spanish party unless it agrees to genuine steps towards a Catalan act of self-determination. Campuzano, a PDECat MP since 1996, commented in the March 20 Ara: “It’s an objective fact that those of us who believe that in the next legislative session in Madrid the emphasis has to be put on avoiding a government of the right are not on the ticket.”

Left alliances unravel

The all-pervasive national question has also been creating havoc around a Unidos Podemos that has been slipping further and further behind the PSOE in opinion-polling—to the point that some polls show the radical left force even coming in fifth behind Vox.

Creating the alliances between Unidos Podemos (coalition of the all-Spanish parties Podemos, the United Left and the all-Spanish green party Equo) and the various left-nationalist and left-regionalist forces that composed the platforms that came close to overtaking the PSOE in 2015 and 2016 was a difficult job--even in those times of rising support and great expectations.

A sign of today’s more sombre mood was the vote in the United Left’s and Equo’s internal consultations on whether to repeat the alliance with Podemos: in 2015, 20,000 United Left members voted and 83% supported the proposal, but this time the participation was just over 10,000 with 61% support. For Equo, the vote in favour was even lower—only 51.7% of its members wanted to continue with the coalition.

The Unidos Podemos core of broader alliances is not even holding together itself for a number of the May 26 regional and municipal contests. In Madrid city and region and in the region of Murcia, the United Left will be running in coalition with Anticapitalists (the most radical tendency in Podemos) in an alliance whose name is yet to be announced.

In Madrid, the alliance is a response to the major split in Podemos Madrid caused by its lead candidate, the party’s former number two Iñigo Errejón, deciding to abandon Podemos and join the team of incumbent Madrid mayoress Manuela Carmena. Left and progressive voters in the Spanish capital and region, who had a single candidacy in 2015, will now have to choose between three: the Errejón-Carmena ticket More Madrid, the official Podemos ticket and the alliance between the United Left and Anticapitalists.

The dynamic of disintegration is affecting the alliance negatively even where it will be presenting a single list. Pablo Bustinduy, its lead candidate for the May 26 European parliamentary election and previously close to Errejón, has withdrawn from the position for personal reasons. In Podemos Andalusia, where Anticapitalists is the ruling force, the candidates for April 28 have been imposed centrally, raising the issue as to how much local members will want to sweat for a campaign in which no respected local leaders feature.

In 2019, the dynamic of hard-won unity between the all-Spanish and left-independentist and left-regionalist forces has generally gone into reverse, as the different alliance partners have increasingly diverged in their assessments of the relative importance of social and national struggles, of how best to meet the threat of the right, how to hang onto past gains—especially important cities won in 2015—and how to carry out candidate preselections.

The retreat has been greatest in Galicia, with the near-complete unravelling of the process of alliance-building that began in 2012 with the creation of the Galician Left Alternative between the left-nationalist formation Anova and the United Left, later to be boosted by the addition of Podemos. The process reached its peak with the conquest by these alliances of the councils of Galicia’s capital, Santiago de Compostela, its largest city A Coruña and ship-building town Ferrol.

By March 16, however, after the decision of Anova not to stand on April 28, Unidos Podemos was reduced to standing without any Galician left-nationalist partner at all. It will also be competing on April 28 with En Marea, formerly the name of the entire coalition in Galicia and now the name of its left-nationalist component..

In the Valencian Country, the left-regionalist force Commitment, which stood with Unidos Podemos in 2016, had already decided by mid-2018 not to renew the pact.

In Catalonia, the Together We Can alliance which topped the vote in 2015 and 2016 has held together for 2019, but nor without desertions by important individual leaders who disagree with what they see as a downplaying of the centrality of the present struggle for Catalan sovereignty—as opposed to a vaguer and more timeless recognition of a Catalan right to self-determination. The most dramatic incident has been the abandonment of the position of general coordinator of the United and Altermative Left (Catalan sister party of the United Left and affiliate of Together We Can) by Joan Josep Nuet.

Nuet, who has also left his seat as a Catalonia Together MP in the Catalan parliament, will be now standing as number four on the ERC ticket for the Congress. He has been accompanied by Elisenda Alemany, the former parliamentary spokesperson for Catalonia Together in the Catalan chamber: she will be the number two on the ERC ticket for the Barcelona Council election. Alemany has cited lack of real commitment by “the commons” to the cause of Catalan sovereignty and defence of the Catalan political prisoners as the reason for her departure.

At the other end of the scale, former United Left coordinator Gaspar Llamazares who has also resigned from the formation, will now be standing as lead candidate for a new outfit called Actua. Llamazares polemicises against a Unidos Podemos which “defends a right to self-determination that does not exist” and “attacks the King in order to weaken the State and smooth the way for the independentists”. Actua will be seeking to occupy the space of those left voters disillusioned with the United Left’s alliance with Podemos with what he calls “a new left formation that stresses social equality and believes in the institutions”.

A consolidated PSOE

In this scene of general turmoil, two parties have so far largely avoided crisis, the ruling PSOE and the ERC, leading in opinion polls in Spain and Catalonia respectively.

In the PSOE, an implicit deal has been done between the party’s regional chieftains (“barons”) and the Sánchez leadership: despite his demotion of the barons’ retainers in favour of his own ministers and other favourites, the PSOE leader has been given the tickets he wants for the general elections and the May 26 European parliamentary poll. In return, the PSOE’s Federal Candidacy Commission—Sánchez’s tool for overriding local decisions—has left the barons’ lists for the May 26 regional and council elections practically unchanged.

As a result, despite 57% of lead candidates for the Congress and 80% of those for the Senate being new, the March 18 meeting of the PSOE’s Federal Committee unanimously endorsed the tickets for both chambers.

The PSOE now looks certain to win a relative majority on April 28, but the critical question in this “existential” election remains the same: can the parties of a rampant right that is sworn to crush the movement for Catalan sovereignty and roll back a swathe of social and democratic gains, together win an absolute majority? Will enough progressive-minded voters, especially the young—of whom, according to the Centre for Sociological Research, only half are so far certain to vote—act to make sure that “they shall not pass”?

[With help from Julian Coppens. Dick Nichols is Green Left Weekly’s European correspondent, based in Barcelona. An initial version of this article has appeared on its web site.]