The Levellers and the 1640s English Revolution

By Graham Milner

In 1649, 360 years ago this year, an experiment in communal land holding and cultivation began on St. George's Hill in Surrey, England, as the principles of a communist society were put into practice by the Diggers – followers of Gerrard Winstanley, a visionary and writer of radical political tracts. This experiment marked an important phase in the development of socialist tendencies in the struggle to defeat the Stuart monarchy in the 1640s. This essay attempts to analyse the dynamics of the revolutionary struggle in England during the 1640s civil war and its aftermath. It concentrates on the emergence and development of left-wing tendencies in the revolutionary movement, and attempts to provide an explanation for the defeat of the aspirations of those tendencies.

Modern socialism as a doctrine and a movement owes much to the contributions of popular movements in the era of the great bourgeois-democratic revolutions. It should never be forgotten that it was the ordinary people who did the fighting and the sacrificing that won the gains of these revolutions, even if the most direct beneficiaries were in fact merely a different stratum of property owners.

If the idea of a 17th century “Puritan'' revolution, propounded by the venerable S.R. Gardiner, is “in eclipse''[1], and if the entire framework supporting the “Whig'' interpretation of English history has been undermined[2], then a corresponding increase in concern by modern historians with the role of the left-wing of the English Revolution has become manifest. This growth of interest in the broader social forces and movements accompanying more immediately visible developments in church and state before and during the revolution has been one consequence of the demise of the “religio-constitutional'' approach to English history.[3]

The fruits of research undertaken by scholars working under the newer disciplines of sociology and social psychology have enabled historians to approach the English Revolution, and the mass movements associated with it, armed with techniques and insights hitherto denied them.[4] The results have already begun to overthrow long-established orthodoxies. For example, the millenarianism (chiliasm) traditionally associated exclusively with extremist sects far removed from the mainstream of pre-revolutionary English religious life is now increasingly regarded as having been widespread in the Puritan opposition and even in the pre-Laudian High Anglican Church.[5] In some aspects, as with the doctrine of “Antichrist'', it has been seen as a ubiquitous phenomenon.[6]

The period between 1645 – the year of the Self-Denying Ordinance, the formation of the New Model army and the Battle of Naseby – and 1653 – the year that saw the dissolution of the Rump Parliament and the onset of the Protectorate[7] – forms the background to the rise and fall of the Leveller movement. The major preceding political events can only be briefly reviewed here.

Shift to the left

The course of events from the calling of the Long Parliament (1640) until 1645 was characterised by a progressive shift to the left on the part of the forces opposed to the king. The leftward movement proceeded through a series of splits and regroupments. Once the initial acts of the Long Parliament (impeachment of Archbishop William Laud and the Earl of Strafford, and the dismantling of prerogative government machinery)[8] were completed, differences developed over the question of the future of episcopacy between the Presbyterian Root and Branch men (radicals), led by Pym and Hampden, and the moderate party favouring limited episcopacy.[9]

The “Grand Remonstrance'' of November 1641[10] marked the decisive break between Royalists and Parliamentarians, with the episcopalian party soon deserting to the king.[11] Once the war was underway the parliamentary forces divided, with the rise of a militant Independent opposition – the “Win the War'' party.[12] The new opposition found its most powerful ally in the Parliamentary army, where the Presbyterian religious settlement, imposed as a condition of the Scots alliance[14] was a major point of contention.

Oliver Cromwell's policy of religious toleration deserves emphasis here, inasmuch as it explains to some extent his popularity in the ranks of the army, above and beyond that consonant with mere military prowess; the two aspects were in fact combined in this “servant of God''.[15] The conflict resolved itself with the Self-Denying Ordinance,[16] which dissolved the rights of peers to command the army. A popular, national “New Model'' army was mobilised and finances were reorganised.[17] The Royalist forces were soon thereafter destroyed at the Battle of Naseby (June 1645). A new conflict later arose between the army leadership (Grandees) and the rank and file: the Levellers were to play an important role throughout the course of this new conflict.

We have picked out a rough outline of the salient points in the struggle between king and parliament from 1640 to 1645, noting how each successive development moved the struggle to a higher level of intensity. These developments took place alongside a growing radicalisation of the masses, reflected in the incidence of sectarianism in the New Model.[18] This radicalisation process frightened the social classes promulgating the war effort (primarily the gentry and the commercial bourgeoisie)[19] to such an extent that they became more concerned with preserving their property and privileges than with prosecuting the war with any fervour[20], the split between Presbyterians and Independents turned fundamentally around this point.

Origins of the Levellers

The origins of the Leveller movement (which in Brailsford's view was not formed as a party until 1647, with the publication of A Remonstrance of many Thousand Citizens)[21] may best be traced by reviewing the activities of its most prominent leaders. John Lilburne (1614-57), the most widely known of these men, was whipped and pilloried for smuggling anti-prelatical literature at the age of 22.[22] He joined the Parliamentary army at the outbreak of war[23] and left it at the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant with the Scots (1643). William Walwyn was generally regarded as the dominant intellectual force in the Leveller movement.[25] It was he who postulated the concept of the “state of nature''. Richard Overton was responsible for the publication of a series of satirical pamphlets viciously lampooning the Presbyterians.[26] John Wildman possessed considerable legal knowledge, and was one of the draftees of the first “Agreement of the People''.[27] All were agreed on the idea of liberty of conscience in religious matters. Continued attempts at press censorship, along with the introduction of an intolerant “Directory of Worship'' in 1645,[28] plunged these four men into “pamphlet warfare'', and Walwyn, Overton and Lilburne published the Marpriest tracts, lampooning religious intolerance.[29] Lilburne was arrested in July 1645[30] and his new pamphlet, England's Birthright Justified,[31] written in jail, marked an increase in concentration on social and economic issues. Tithes were challenged in Overton's The Ordinance for Tithes Dismounted[32] and, in the opinion of the propertied classes, this tack implied assault on all property rights.

The unstable balance of social forces in the post-war situation of 1646-7 provided an opportunity for Leveller ideas to gain strength in the New Model. A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens[33] contained the germs of a popular program, demanding the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords. Lilburne's London's Liberty in Chains Discovered, written in prison, denounced the commercial oligarchy of the City of London and called for unity among small craftsmen. Royal Tyranny Discovered[35] demanded the execution of the king for treason and utilised the well-worked myth of the Norman Yoke.[36] The “Large Petition'' of March 1647[37] contained the most fully worked-out program to that date, calling for the abolition of monarchy and lords, full religious toleration, abolition of tithes and monopolies, and legal reforms. This document appeared alongside growing Leveller organisational efficiency and influence among the rank and file of the New Model army.[38]

The Presbyterian parliamentary majority's fears of growing radicalism in the army led it to attempt the demobilisation of the New Model army without payment of arrears, in March 1647.[39] The army rebelled, elected representatives (called agitators) to an Army Council[40] and published the famous declaration of June 14, 1647:

We shall before disbanding proceed in our own and the kingdom's behalf to propound and plead for some provision for our and the kingdom's satisfaction and future security...especially considering that we were not a mere mercenary army, hired to serve any arbitary power of a state, but called forth and conjured by the several Declarations of Parliament to the defence of our own and the people's just rights and liberties.[41]

The army's declaration concided with the publication of the Leveller's “Large Petition'', the June “Solemn Engagement'',[42] authored by Henry Ireton, was the product of a compromise worked out between moderate Grandees and radical agitators.[43] An uneasy alliance between these two groups lasted through the summer, until the Leveller-inspired agitators compelled the Grandees to break off negotiations with the king and project a march on London.[44] The financial oligarchy of the City of London had been pressuring the Presbyterian MPs to withdraw concessions made to the New Model commanders, and the king was subsequently invited to London.[45] Independent members fled to the New Model lines, and the Presbyterian City oligarchy prepared to defend London. The city was captured, however, without a fight.[46]

Autumn 1647 saw the nascent conflict between Grandees and agitators develop into open hostility. The Levellers demanded an end to the continuing negotiations with the king, and the release from prison of Lilburne and Overton.[47] The Case of the Army Truly Stated, published in October 1647,[48] called for the restoration of enclosed common lands and of other “ancient rights and donations belonging to the poore''[49]. Shortly afterwards appeared the first “Agreement of the people''[50] summarising the basic principles of the Levellers on constitutional issues, and forming their negotiating document at the famous debates with the Grandees held at Putney in October 1647[51]. These debates, turning mainly around Leveller proposals for an extended franchise,[52] were inconclusive. The flight of the king to the Isle of Wight in November (which might have been engineered by Cromwell)[53] played into the Grandees' hands. The discussions in the army were broken off by Cromwell and, after a rebellious regiment stationed at Ware was subdued,[54] discipline was effectively restored. The Ware events marked a major setback for the Levellers as “... all subsequent attempts to revive the Agitator movement were promptly suppressed''.[55]

Under the changed circumstances the Leveller party had to resort to the strategy of petitioning parliament. The “Earnest Petition'' of January 1648,[56] called for decentralisation measures and for local election of magistrates. The latter was a frontal attack on the prerogatives of justices of the peace, and through them on landed property and its priorities. The brief, so-called “Second'' Civil War was resolved in parliament's favour with the defeat of the Scots at Preston (1648).[57] In the interests of unity and discipline there was a lull in Leveller criticism of the Grandees during the hostilities. The Levellers' campaign revived with the “September Petition''.[58] Although this document called for the execution of the king, the Grandees' position on this issue had in any case hardened.[59]

On constitutional questions, particularly those relating to the franchise, there is evidence that the “September Petition'' represents a compromise with the Grandees. On their part the Grandees adopted to some extent sections of the Leveller program, perhaps partly as a result of negotiations with Leveller representatives. The Levellers had demanded some guarantee against military dictatorship before they would consent to a trial of the king.[60] Ireton's Remonstrance of the Army,[61] presented to parliament in November, contained some radical proposals: biennial parliaments; abolition of monarchy and House of Lords, and the establishment of a constitution based on some kind of contract or agreement of the people.

Continuing negotiations between the parliamentary Presbyterians and Charles I resulted in Ireton ordering the king's arrest, and on December 6, Colonel Pride excluded the Presbyterian members from parliament.[62] The remaining Independent “Rump'' parliament passed three resolutions: that original power resided in the people; that supreme power rested with the House of Commons (representing the people) and that Acts of the House of Commons were law even without the consent of king or peers.[63] The Levellers drew up a new “Agreement of the People''[64] and presented it to the Rump; it was by then obvious, however, that they had been gulled and that the new republic had no intention of acting upon Leveller principles.

Soon, from Lilburne, came denunciations of the trial, under a new High Court, of five royalist peers[65] – and of martial law. In February 1649 a new pamphlet, England's New Chains Discovered[66] attacked the Grandees and the new Council of State.[67] The army was, however, in the main loyal to Cromwell. It is an indication of the Levellers' waning influence that their literature from this period becomes increasingly unrealistic, calling for armed rebellion against the rule of the Rump, and even at times flirting with Royalist sympathies – as the “lesser evil''.[68] Overton's pamphlet The Hunting of the Foxes contained outspoken calls to armed rebellion.

Essentially accepting Christopher Hill's analysis, I have identified the Leveller movement with the radicalised petty bourgeosie. Obviously this is a far from unanimous opinion among historians[70] and so a brief examination of the social composition of the movement is perhaps necessary to demonstrate the accuracy of that analysis. By so doing it may also be possible to provide some understanding of the factors behind the defeat of Leveller aspirations.

Levellers' social composition

There is a general consensus that the Levellers' popular base was neither primarily among the large population of landless agricultural labourers and dispossessed, nor with the wealthier property-owning classes as such, but with the intermediate layers – small proprietors, poorer yeomen farmers, urban craftspeople and traders. Lilburne himself described the Levellers' main area of support as stemming from the “the middle sort of people''.[71] As one consequence of a range of economic tendencies at work through the previous century, this intermediate social layer was going through a process of transformation.

These tendencies included an increase in agricultural production for the market[72] and a concomitant steady erosion of medieval survivals in the social relations of agricultural production.[73] There had been continuing attacks on the rights of copyhold, the manorial system of land tenure, throughout the 16th and continuing into the 17th centuries. The triumph of freehold land tenure[74] and extended enclosures of common land[75] were two aspects of this process. In the towns was witnessed the slow transformation of the medieval guilds into structures dominated by the concentrated wealth of burgher oligarchs.[76] The continuing widespread social distress that had necessitated the adoption of the Tudor Poor Laws, combined with a steep rise in prices,[77] and a conjunctural economic crisis and a series of poor harvests,[78] conspired to make the years between 1620-50 “among the most terrible in English history, bringing extreme hardship for the lower classes''.[79]

The long-term effect of these economic developments was to pauperise large sections of the petty bourgeoisie, while converting a small percentage of it into more or less successful capitalists.[80] It is basically due to the extension of these tendencies into the 18th century that the yeoman class, which formed the backbone of Cromwell's army, had by 1750 virtually disappeared.[81] The contradictions within Leveller ideology may also be traced, in the last analysis, to these fundamental antagonisms embodied in long-term socioeconomic trends. The characteristics, and fate, of petty proprietorship also provide an explanation for Christopher Hill's paradoxical view, expressed in rather uncompromising terms in 1940, that “in Puritan social ideas and Leveller ideology, there is a trend that is medieval and even reactionary''.[82]

Leveller ideology

Turning to the concrete issues of Leveller ideology, there are two important points of controversy that deserve special attention. The question as to whether the Levellers' ideas were religious or secular in inspiration[83] is in my view a non-issue. Political opposition of every hue in early 17th century England was invariably expressed in religious terms: the official church had a monopoly in ideas until the revolutionary events of the 1640s. As Hill points out:

The Independent and Sectarian congregations were the way in which ordinary people organized themselves in those days to escape from the propaganda of the established Church and discuss the things they wanted to discuss in their own way.[84]

Religion and politics were in fact inseparable. The question of lineage in discussing Leveller ideas is largely an irrelevant one; inevitably they were religious, inevitably they were connected with militant Puritanism, with Anabaptism and antinomianism. For only with the rise of a free press during the revolutionary years did there arise secular ideologies[85] or ideologies that were close to a secular position (e.g. pantheism). To claim that Puritanism was a two-edged sword, that it had an inherent tendency to split into sects once the common enemy was removed[86] is really to beg the question; for it was the propertied classes of all shades who consistently opposed the concept of freedom of ideas or conscience, because these classes understood the importance of a centralised religious orthodoxy as the essential bulwark of a system based on inequality and exploitation. Cromwell's supposed “religious toleration'' may easily be seen as having been based on opportunism, as perhaps his and Fairfax's acceptance of doctorates from the Royalist stronghold of Oxford University indicates.[87]

The position of the Levellers on the franchise (expressed in the “Agreement of the People'' and other documents) has been the subject of controversy, especially since the publication of Professor C.B. Macpherson's study of the problem in his book The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism (1962). Macpherson's thesis is that underlying Leveller statements about “manhood suffrage'', “the people'', “freedom'', etc., are assumptions that limit their application and, in terms of modern understanding, deny their content.[88] MacPerson argues that these assumptions are shared in common with other 17th century political theorists, including Hobbes and Locke, so that concepts of natural rights, political obligation and representation (where present) are refracted through a limited bourgeois view of society. The social relations of the “possessive market'' society being hidden (reified), have been either restructured artificially in some form of contract theory of obligation (as in Locke) or, in the case of the Levellers, identified with the personal attributes of individuals:

The propriety of the person. The Leveller writers saw that freedom in their society was a function of possession. They could therefore make a strong moral case for individual freedom by defining freedom as ownership of one's person.[89]

On the franchise issue, discussed at Putney, the Levellers' “possessive market assumptions'' led them to exclude servants and wage labourers from those who should be granted the right to vote, as these people had “sold their birthright'' – or their labour (“right'') was included in that of their master. Macpherson's thesis has been attacked on some points. He has been accused of misreading the Putney documents and criticised over his interpretation of population statistics.[90] If Macpherson's views do hold good, and they are now increasingly accepted, then the view of the Levellers as a radical plebeian or petty-bourgeois current must gain credence, while that of their position as ancestors of popular democracy[91] must be thrown into doubt (according to Macpherson's reading of the statistics, under the Leveller proposals at Putney only an extra one sixth of the population would have received the vote).[92]

The last prominent act of the Levellers before their final defeat was to oppose Cromwell's Irish campaign.[93] This they did from an ethical standpoint. In The English Soldier's Standard,[94] by recognising the right of the Irish to self-determination, the Levellers could be seen as having made a further significant contribution to a secular political creed based on formal democratic criteria. Political arraignment among the army rank and file was renewed and, in May 1649, six regiments elected agitators.[95] This attempted mutiny was put down by the Grandees at Burford.[96] The Burford defeat marked the eclipse of the Levellers.

My standpoint on the question of Leveller decline and collapse has perhaps emerged fairly clearly from the preceding analysis; nevertheless, differing viewpoints need some examination if a rounded conclusion on the Levellers' place in history is to be reached. In my view the basic dialectic of the Civil War was laid bare by Christopher Hill in his 1940 essay (building partly from the contributions of previous socialist historians, such as Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky):[97]

[Hill]... there were really three classes in conflict. As against the parasitic feudal landowners and speculative financiers, as against the government whose policy was to restrict and control industrial expansion, the interests of the new class of capitalists, merchants and farmers were temporarily identical with those of the small peasantry and artisans and journeymen. But conflict between the two latter classes was bound to develop, since the expansion of capitalism involved the dissolution of the old agrarian and industrial relationships and the transformation of independent small masters and peasants into proletarians.[98]

This broad dialectic was narrowed to a fine edge in the events of 1647-48, when the future of England seemed to balance precariously between two possible outcomes: either victory to the Grandees and the consolidation of the gains of a strictly bourgeois revolution, or the sweeping changes outlined in Leveller manifestos, consonant with a victory to the army rank and file. But was the latter variable ever a serious possibility? If we allow that it was, then the outcome of the Civil War could obviously have been far different from that of the dictatorship of the Rump, followed by the Protectorate and, after Cromwell's death, by the Stuart restoration. But what if, without admitting into our analysis so much as a hint of determinism, such an outcome was not on the cards, and that the rule of the Rump and Cromwell – the dictatorship par excellence of the bourgeoisie – was the only logical outcome of an extremely limited number of possibilities inherent in this particular historical conjuncture? After all, the apparently wide and powerful influence of the Leveller party among the rank and file of the New Model army may be seen as having been largely illusory. As the historian H. Shaw points out:

... their influence grew or diminished according to the prevailing political situation. Thus, in 1648, just before Pride's Purge, when the Grandees wanted allies, the Levellers appeared powerful; at Ware and Burford, when the Grandees wanted to exert their authority, the party's real weaknesses are exposed.[99]

Why was this? For such a vocal and apparently widespread movement to be so treated must imply that something was seriously amiss with its internal cohesion. Brailsford can of course claim, perhaps a little sentimentally, that the Levellers never really died at all, but merely faded away, and were in fact still at the height of influence in 1649.[100]

We can list factors behind the defeat: the consolidation of power in the Rump; mitigation of economic hardship to some extent, thus relieving the plight of the urban and rural poor; programmatic weaknesses (and the partial co-option of their program by the Grandees in 1648); exclusion of the wage-labouring class (if we accept Macpherson's thesis) from the Leveller franchise; lack of unity – and behind that the disparity of the social forces that the party was supposed to represent. All these factors have truth in them; they are, however, at root variations on the same theme – the peculiar weaknesses in social composition of the Levellers.

It was, as Hill maintains, a movement that represented an exceptionally amorphous class – the petty bourgeoisie; a class congenitally incapable of organising itself effectively, because of the fragmented and diversified character of its role in production.[101] The Levellers' primary stronghold was among the rank and file of the New Model.

This point is crucial – for this was precisely an artificial environment produced by the wholly unusual circumstances of the Civil War. Here radical political ideas could flourish among an amorphous class temporarily unified.[102] However, the New Model army was not mobilised to fight the class battles of the small proprietor, but those of the bourgeoisie. Thus the Leveller movement, although extremely articulate, and possessed of capable, even brilliant, leaders, could not win hegemony over the social forces that made the English revolution. For much of their political lives, the Levellers were limited to petitioning the existing regime (the bourgeois Grandees), staging flamboyant court appearances,[103] and organising elaborate funerals for their martyred followers. They were, in short, a party of protest.[104]

The demise of the Levellers left the field in the New Model army to increasingly wild and improbable millenarian sects. The most prominent of these were the Fifth Monarchists, who believed that the reign of Christ was shortly to begin.[105] The ascendancy of such tendencies in the rank and file of the army marked a trend away from political organisation and activity, towards reliance on the “second coming'' – it was the signal of defeat for the whole radical left wing of the English revolution. Apart from a few sporadic risings during the 1650s,[106] the dominant movement was towards quietism, as with the Quakers. After 1660, this movement became even more pronounced as Puritanism turned into non-conformity.

Diggers

One group deserves special attention however – the Diggers, or True Leveller movement – which developed possibly the most sophisticated political philosophy of any of the left-wing tendencies, through the thought of Gerrard Winstanley. Although expressed in “the Biblical idiom which Winstanley shared with almost all his contemporaries'',[107] his ideas mark a distinct departure from Leveller “possessive-market'' assumptions, to the standpoint of the propertyless, agricultural labourer. Winstanley's program called for the settlement of common land by the poor, and its collective cultivation.[108] A small Digger colony was established in April 1649 on St. George's Hill in Surrey. The colony did not operate for long before it was driven off the land,[109] but the writings of Winstanley, published as Digger manifestos, survive as significant political tracts.

Winstanley postulated a primitive libertarian communism.[110] He regarded the clergy as propagandists in the service of the exisiting property system.[111] Winstanley's profound idea of economic equality, based on a communal organisation of society, formed the important legacy handed down by the Diggers to the working-class movements of the future.

Notes

1. Christopher Hill, Recent Interpretations of the Civil War: Puritanism and Revolution: Studies in Interpretation of the English Revolution of the 17th Century, London, Panther Books, 1968; original edition 1958), p.15.

2. Apart from S.R. Gardiner, well-known proponents of the Whig interpretation include Macaulay, Froude and Trevelyan. The publication of Herbert Butterfield's conservative tract The Whig Interpretation of History in 1931 marked the opening salvo in a flood of attacks. See E.H. Carr, What is History?, Harmondsworth, 1964, pp.41-2. For an acute analysis of 20th century English historiography in general, see Gareth Stedman Jones, “History: the Poverty of Empiricism'', in Robin Blackburn (ed.), Ideology in Social Science, London, 1972, pp.96-118.

3. See Lawrence Stone, The Causes of the the English Revolution 1529-1642, London, 1972, chapter 2.

4. The popularisation of Weber's sociology of religion (outlined in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism) through R.H. Tawney's Religion and the Rise of Capitalism provided the basic analysis of Puritanism as an ideology associated with the nascent English bourgeoisie. The published work of Christopher Hill (who wrote a pioneer Marxist account of the Civil War in 1940, cited below) incorporates much of the valuable work done internationally in sociology and social psychology.

5. Two studies are W.M. Lamont, Godly Rule: Politics and Religion 1603-60 (London, 1969) and Hill, Antichrist in Seventeenth Century England (Oxford, 1971). Norman Cohn's The Pursuit of the Millennium (London, 1970) contains useful European background material, and has an appendix on the Ranters.

6. Hill, Antichrist in Seventeenth Century England, pp.31-2.

7. A brief table of events is appended to Conrad Russell, The Crisis of Parliaments: English History 1509-1660.

8. J.R. Tanner, English Constitutional Conflicts of the Seventeenth Century 1603-1689 (Cambridge, 1928) pp.92-9.

9. Ibid. pp.100-104.

10. J.P. Kenyon (ed.), The Stuart Constitution: Documents and Commentary (Cambridge, 1966) doc. 64, pp.228-41.

11. G.M. Trevelyan, England Under the Stuarts (London, 1904), pp.210-14.

12. Hill, God's Englishman: Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution (Harmondsworth, 1972), ch.3, sections 3, 4.

13. Hill, The Century of Revolution 1603-1714 (London, 1961), pp.104-5.

14. Tanner, English Constitutional Conflicts, pp.122-23; Russell, Crisis of Parliaments, pp.355-56; Trevelyan, England Under the Stuarts, pp.244-5.

15. See Hill, God's Englishman, ch.3, section 5 (religious policies) and ch.6 (military prowess).

16. Tanner, English Constitutional Conflicts' pp.130-01; S.R. Gardiner (ed.), Constitutional Documents of the Puritan Revolution (Oxford, 3rd ed., 1958) pp.287-88.

17. Tanner, English Constitutional Conflicts, pp.131-32. Jack Lindsay, Civil War in England (London, 1954), ch.16.

18. Hill, Century of Revolution, p.148. The pious Edwards' Gangraena (1646) catalogues the growth in influence of sectaries in the New Model: see H.N. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution (London, 1961), ch.3, passim.

19. The debate surrounding the class lineup in the Civil War is far from closed. It is not, however, within the scope of this essay to more than point out the differing viewpoints. See the material on the subject already cited, and also Conrad Russell (ed.), The Origins of the English Civil War (London, 1973), esp. bibliography pp.258-64. Christopher Hill's analysis is the one basically accepted for our purposes.

20. Hill, The English Revolution, 1640 (London, 1940), p.46.

21. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, p.86.

22. Ibid., p.80; see also Maurice Ashley, “Oliver Cromwell and the Levellers'', History Today (August, 1967) p.539.

23. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, p.86.

24. Ibid., p.89.

25. H. Shaw, The Levellers (London, 1968), p.30; Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, pp.61-2.

26. Shaw, The Levellers, p.33.

27. Ibid., p.34.

28. Kenyon (ed.), The Stuart Constitution, pp.255-56. No machinery was set up by parliament to enforce this Directory (a product of the Scots alliance); see also Hill, Century of Revolution, p.148.

29. These pamphlets were a parody of the Elizabethan Marprelate tracts. See Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, pp.53-4.

30. Ibid., p.90; Shaw, The Levellers, p.41.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid., pp.41-2.

33. D.M. Wolfe (ed.), Leveller Manifestos of the Puritan Revolution (New York, 1944), pp.109-31.

34. Shaw, The Levellers, p.46.

35. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, p.117.

36. This aspect of Leveller ideology is discussed in Hill, “The Norman Yoke'', Puritanism and Revolution, ch.3.

37. Wolfe (ed.) Leveller Manifestos of the Puritan Revolution, pp.131-42. A disclaimer against accusations of communism is contained in this document.

38. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, p.354-55. The Levellers had by this stage established a weekly newspaper, The Moderate, which was widely distributed.

39. Hill, Century of Revolution, p.105; Tanner, Constitutional Conflicts, pp.141-42.

40. Eduard Bernstein, Cromwell and Communism: Socialism and Democracy in the Great English Revolution (New York, 1963; orig. German ed., 1895) p.62.

41. Kenyon (ed.) The Stuart Constitution, document 84, p.296. See also W.Haller and G. Davies (eds.), The Leveller Tracts 1647-1655 (New York, 1944), pp.51-63.

42. Shaw, The Levellers, pp.54-5.

43. Ibid.

44. Charles had rejected the Grandees' “Heads of Proposals'', drawn up by Ireton, which had called for limited restored monarchy. The king's strategy was basically to play off one side against the other in the conflict between parliament and army. See Lindsay, Civil War in England, p.236.

45. Shaw, The Levellers, p.56.

46. Ibid., p.57.

47. No note.

48. Haller and Davies (ed.), The Leveller Tracts, pp.65-87.

49. Ibid., p.82.

50. Kenyon (ed.), The Stuart Constitution, document 86, pp.308-10.

51. See A.S.P. Woodhouse, Puritanism and Liberty (London, 1951), pp.1-124.

52. See below for further discussion.

53. The flight of the king certainly came at a propitious time for Cromwell and the Grandees. Brailsford, however, concluded against Cromwell's complicity. See The Levellers and the English Revolution, pp.292-93. Hill is less certain, see God's Englishman, pp. 92-4.

54. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, ch.14, passim.

55. Shaw, The Levellers, p.66.

56. Wolfe (ed.), Leveller Manifestos of the Puritan Revolution, pp.259-73.

57. For a detailed account, see Lindsay, Civil War in England, ch.23, passim.

58. Wolfe (ed.), Leveller Manifestos, pp.253-73.

59. Shaw, The Levellers, p.70; Lindsay, Civil War in England, p.269.

60. Shaw, The Levellers, p.72.

61. Woodhouse (ed.), Puritanism and Liberty, pp.456-65; Tanner, Constitutional Conflicts, p.152.

62. Tanner, Constitutional Conflicts, p.152; Kenyon, The Stuart Constitution, pp.293-94; Lindsay, Civil War in England, pp.270-1.

63. See Kenyon, The Stuart Constitution, document 90, “Commons' resolution, January 4, 1649'', p.324.

64. Gardiner, Constitutional Documents, pp.359-71.

65. Shaw, The Levellers, p.78.

66. Haller and Davies (ed.), The Leveller Tracts, pp.156-90.

67. The Council of State of the purged parliament (Rump) was, as Brailsford notes, “armed with formidable powers; like one of the prerogative courts of the monarchy; it could summon, question and imprison whom it would'' (The Levellers and the English Revolution, p.469). Hill notes that “the English republic rested on a very narrow social basis'' (God's Englishman, p.99). The views of Leon Trotsky are of some interest here, as this man was an outspoken partisan of ruthless dictatorial measures during crucial periods of the progress of revolutions. See his defence of the Rump and Cromwell in “Where is Britain going?'', in George Novack (ed.), Leon Trotsky on Britain (New York, 1973), ch.6, and his brief, comparative study of dual power in the English Revolution, in The History of the Russian Revolution (London, 1967), vol. 1, ch. xi. A more recent book which attempts to draw historical parallels between four different revolutions is Crane Brinton's The Anatomy of Revolution, New York (rev. ed., 1965), esp. ch. vi, “The Accession of the Extremists''.

68. Hill, God's Englishman, p.140; Ashley, Oliver Cromwell and the Levellers, p.542; Shaw, The Levellers, pp.86-7.

69. The full title was The hunting of the Foxes from Newmarket and Triploe Heaths to Whitehall by Five Small Beagles (Late of the Army). The Grandees were the foxes. See Wolfe (ed.), Leveller Manifestos.

70. Conrad Russell, for instance, disagrees. In his view the Levellers appear as the bourgeoisie, and the victors of the revolution are the Whig magnates; see Crisis of Parliaments' pp.372-73.

71. Cited in Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, p. 527. George Novack's Democracy and Revolution (New York, 1971) provides a particularly clear picture of the Levellers' class composition and ideology, ch.iii, passim.

72. Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution, vol. 2 of the Pelican Economic History of Britain (Harmondsworth, 1969), ch.iii, passim.

73. Ibid., See also Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, ch.ii, section i for European background.

74. Shaw, The Levellers, pp. 11-13, and ch.ii, passim. Hill, Reformation, etc, pp.69-70.

75. G. Davies, The Early Stuarts (Oxford, 1955), pp.279-80; Hill, Reformation, etc., pp.69-70.

76. Shaw, The Levellers, p.13; Hill, English Revolution, p.25. Hill notes here that the financiers lined up with the king, the reason being that “the guilds were so many vested interests linked up with the social structure of feudalism, opposed to the newer, freer forces of capitalism''.

77. Hill, Reformation, etc., pp.82-4; Russell, Crisis of Parliaments, ch.ii.

78. Shaw, The Levellers, p.15. This situation was partly a product of the Civil War's impact.

79. Hill (ed.), Winstanley: The Law of Freedom and Other Writings (Harmondsworth, 1973), Introduction, pp.20-21.

80. This process is described in Hill, The English Revolution, p.24.

81. Karl Marx, Capital, vol. I (Moscow, 1961), pp.722-23.

82. Hill, The English Revolution, p.22.

83. This issue has been the subject of a number of books and articles. The politico-religious dichotomy is discussed by J.C. Davis, “The Levellers and Christianity'', in Brian Manning (ed.), Politics, Religion and the English Civil War (London, 1973): religion is considered primary. See also D.W. Robertson's The Religious Foundations of Leveller Democracy (New York, 1951), which comes to the rather vacuous conclusion that “Levellerism was not a religious movement strictly speaking, but the movement got its impetus and much of its sustained strength from the Christian faith'', p.122.

84. The English Revolution, p.45. See also Hill and E. Dell (eds.) The Good Old Cause: the English Revolution of 1640-60; its Causes, Course and Consequences: Extracts from Contemporary Sources (London, 2nd Ed., 1969), Introduction, pp.21-3.

85. Another important factor was the rise of empirical science in the 17th century. See Hill, Intellectual origins of the English Revolution (Oxford, 1965): “In the eighty years before 1640 England, from being a backward country in science, became one of the most advanced'', p.15. This development was obviously not unconnected with the rise of capitalism. Hobbes was the first to systematically apply empiricist methodology to political theorising: see Hill, “Thomas Hobbes and the Revolution in Political Thought'', in Puritanism and Revolution, pp.267-89. By the time of Locke, the theorist of the Whig Revolution, one could say that the bourgeoisie had effectively harnessed secular political theory for its own purposes.

86. Two historians of the Levellers, at least, have implied this: J. French, The Levellers (Harvard, 1955) notes the “centrifugal tendency'' inherent in Calvinism (and thus the explanation for the tendency to split), p.4. Shaw, The Levellers, notes its “dual nature'', p.3.

87. Hill, Century of Revolution, p.121. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution considers that “Cromwell was never the pioneer of toleration. To his opponents ... Cromwell was never tolerant. What he felt, in spite of unessential differences, was a sense of fraternity for all his fellow Puritans. The name for that state of mind is not tolerance.'' Hill disagrees, estimating Cromwell as on the left on religious issues: see God's Englishman, p.75.

88. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke (Oxford, 1962), ch.3, passim and pp.266-67.

89. Ibid., p.266.

90. A.L Morton's critique, “Leveller Democracy – Fact or Myth?'', in The World of the Ranters: Religious Radicalism in the English Revolution (London, 1970) makes a few useful points, e.g. that the Leveller documents were not “... merely abstract statements of political theory – they were party programmes, weapons in an active political campaign and modified from time to time in accordance with the changing situation and the practical needs of the struggle. It is therefore necessary to look at them not only from the standpoint of political theory, as Professor Macpherson seems too inclined to do, but in relation to the events then actually taking place'', p.202. This comment includes a necessary thrust against Macpherson's methodological standpoint. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism is not a work of history as such, but a book attempting to re-evaluate 17th century political ideology by means of close logical argument and textual exegesis. Any limitations the book has are definitely suffered in general by empiricist “political science''. In other points he raises, Morton seems to misunderstand Macpherson's arguments, and his final position is a mere statement of faith: “I find it impossible to believe, with the whole evidence of their lives and writings before me, that when they spoke of 'the people', or the 'free-born commons of England' or 'the poorest that lives', these men intended in principle the tacit exclusion of any part of the English nation, whatever exceptions might in practice be demanded by existing circumstances'', p.219. Morton appears to be quite unaware that at least one half of that ‘English nation' was not only most certainly excluded from the Leveller franchise, through all its phases (see Macpherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, p.296), but also from his own consideration – women.

91. For an uncritical view of the Levellers in this light, see A.D. Lindsay, The Essentials of Democracy (Oxford, 2nd ed., 1935), pp.11-19, and compare this view with Ashley's remark that they “left practically no intellectual mark upon subsequent political thinking'', Oliver Cromwell and the Levellers, p.539.

92. Macpherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, pp.114-15, and appendix, pp.279-92.

93. See Hill, God's Englishman, pp.105-18, for a discussion of the issues involved.

94. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, pp.497-509.

95. Ibid., ch.26, passim.

96. Ibid.; Hill, God's Englishman, p.105; Shaw, The Levellers.

97. Cromwell and Communism (see above).

98. Hill, The English Revolution, p.27.

99. Shaw, The Levellers, p.95.

100. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution, p.607.

101. Hill's point of view owes much to Marx and Lenin. The following texts may provide useful background: Marx's critique of Proudhon, The Poverty of Philosophy (New York 1963; orig. ed. 1846); Marx, Engels, Lenin, On Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism (New York, 1972), V.I. Lenin, Left-Wing Communism; an Infantile Disorder (Moscow, 1966).

102. Bernstein notes: “The army was the organised democracy of the country, the bulk of it consisting of yeomen and artisans'', Cromwell and Communism, p.61.

103. Lilburne's famous trial at the Guildhall shortly after the Burford fiasco is a case in point. See Shaw, The Levellers, pp.88-9.

104. As Hill has remarked: “The Levellers were never a united, disciplined party or movement, as historians find to their cost when they try to define their doctrines with any precision'', The World Turned Upside Down (London, 1972), p.91.

105. Russell, Crisis of Parliaments, pp.356-57; Hill, Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution, p.296.

106. For example Venner's rising of June 1657: “The 42 months of the Beast's (i.e. the Protector's) dominion having expired at that time''. See Hill, Antichrist, p.123.

107. Hill (ed.), Winstanley, p.19.

108. Four days before the execution of Charles I, Winstanley announced: “when the Lord doth show unto me the place and manner, how he shall have us that are called common people to manure and work upon the common lands, I will go forth and declare it in my action, to eat my bread with the sweat of my brows, without either giving or taking hire, looking upon the land as freely mine as another's ... the spirit of the poor shall be drawn forth ere long, to act materially this law of righteousness'', cited in ibid., p.23.

109. For a history of this colony, see D.W. Petegorsky, Left-Wing Democracy in the English Civil War (London, 1940) ch. iv, passim.

110. See George Woodcock, Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (Harmondsworth, 1963) pp.42-6.

111. “The True Levellers Standard Advanced'', in Hill (ed.), Winstanley, pp.77-80; 99-101.

The Last Stand of the Levellers

Excellent article!

Here's another of interest.

By Dudley Edwards

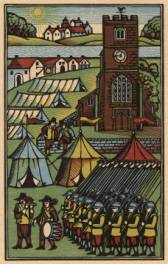

On 17 May 1649, three soldiers were executed on Oliver Cromwell’s orders in Burford churchyard, Oxfordshire, England. They were the leaders of 300 men who belonged to the movement known as the Levellers. They had decided to fight against Cromwell who they considered was betraying the ideals of what the “Civil War”, i.e. the English Revolution, had been about.

Introduction

This lengthy article was written by Dudley Edwards in 1947-48 to commemorate the three-hundredth anniversary of the mutiny in 1649 of regiments of Cromwell's army stationed in Salisbury at the end of the Civil War. It is based on Leveller pamphlets stored in the records department of Oxford Corporation.

The Levellers came from within the New Model Army built by Cromwell which was made up of free yeomen, smallholders and the like. They were the men who did the fighting for Cromwell and fought valiantly in the belief that the struggle was about the return of basic freedoms such as ending the enclosure of common land, establishing religious tolerance and putting an end to taxation to finance the church. All this they had been promised by their leaders.

However, by 1649, the soldiers started to realize the true nature of these “leaders”. The latter had started to raise themselves above the men who had done most of the fighting and this created a spirit of anger and revolt among the ranks. The most determined of these gathered around John Lilburne ‑ who after Cromwell was the most respected leader ‑ demanding that what they had fought for be implemented. They became known as the "Levellers", i.e. those who sought justice and equality, and mostly emanated from the “lower orders”, the poor. And although the conditions of the time did not allow for a fully fledged socialist movement to develop, the Levellers were striving for the rights of the working people. In one of their pamphlets, The Mournfull Cries of Many Poor Tradesmen, published in 1648, we find the following meaningful question: "Is not all the controversie whose slaves the poor shall be?"

Resentment at the new set up, which implied an open betrayal of the ideals many of Cromwell’s men had fought for, led to mutinies, the leaders of which were either shot, imprisoned or exiled. Dudley Edwards’ describes these events, and shows how Cromwell, having established the new bourgeois order, proceeded to crush those who wanted to go beyond the limits imposed by the new class relations that had emerged.

The Levellers lost and were defeated, but their experience should not be forgotten by all those who are struggling for an end to the present oppressive system of capitalism. Now the conditions for a genuinely egalitarian society exist and the aspirations of those courageous fighters can finally become reality. Dudley Edwards in 1975 did a service to the movement by digging out this important part of the history of the working people of Britain.

The Last Stand of the Levellers

The levellers manifesto

Three hundred years have passed since the revolutionary artisans and yeomen of Cromwell's army fought their last battle to win for the common people something more than a mere exchange of masters.

Battle scarred, iron disciplined and politically conscious, they saw that the overthrow of absolute monarchy and absolute tyranny was leading only to a change of taskmasters, and that the great parliamentary generals including even Cromwell himself were betraying the interests of the masses to the Presbyterian merchant capitalists of the City of London. They knew that these sanctimonious war profiteers, victuallers and country squires now intended to reap for themselves the economic fruits of the Civil War and awaited eagerly the opportunity to buy up the requisitioned estates of the defeated Royalists at knockdown prices. To realise their aims, however, they first had to destroy the growing power of the politically aroused petit-bourgeois masses, the artisans and craftsmen, who in the large cities were beginning to form the nucleus of a working class, and from which had sprung, in the main, the rank and file of the New Model Army.

This mass of NCOs and privates, once cheered on but now scorned by the city merchants, represented the cadres of the common people. Their political morale had been carefully attended to by Cromwell himself who was the first general to realise that intense conviction and faith in its cause enables a mainly civilian army to defeat the traditional and ready-made military skill of an old ruling class. For this very reason, Cromwell had encouraged the development of the first peoples' army. Towards the end of the Civil War it had become, in fact, the first genuinely revolutionary army in history. In some respects its democratic structure was more complete than that of the revolutionary armies of France. Only three hundred years later can an adequate comparison be found in the revolutionary spirit and solidarity of the Red Guard detachments created by Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolshevik Party during the overthrow of Tsarism in 1917.

It is not the intention of the present writer, a non-academic worker-student, to evaluate the role of Cromwell in this historic struggle, nor the effect of his activities on the ultimate growth of the working class movement, as this is being done by more professional Marxist historians. That Cromwell was the great realist statesman of those stormy days there seems little doubt, and it is probable that he carried forward the English bourgeois revolution as far as the economic and social conditions of the period would permit. It does not follow from this, however, that the Levellers, who in the end bitterly attacked Cromwell, were hopeless visionaries hitting out blindly against a political brick wall. For several years their policy represented the only serious alternative to Cromwell's. Their immediate programme was a realistic one based upon the facts and issues of the day, reflecting the genuine grievances of the masses. Their movement was no "flash in the pan" but a well organised and intelligently-led struggle lasting over several years. Many of them were the very men upon whom Cromwell had relied to maintain the morale of the army during the darkest days of the civil war; dour, hymn-singing soldier-agitators, often self-educated and ever-ready with an apt biblical text whenever their men needed inspiration in their battles with the "forces of Baal", as they called the Royalists. Such veterans as these were a formidable force and Cromwell had to use all his immense prestige, political cunning, and even deception to defeat them. Indeed, if it had not been for this the final battle at Burford might have had another result.

The final stages of this struggle were extremely tense and all England must have been agog with rumour during these dramatic months of 1649, yet for several hundred years after, few national history books are found which devote more than a few lines to the whole movement. No graves of the four ringleaders shot against Burford churchyard wall can be found and their memory was buried so deeply by the bourgeois historians that their very existence was almost forgotten by the common people for whom they fought.

Today the working class movement with the aid of the Marxist theory of social development is able to revive the revolutionary traditions of the English people, and with the advance of Socialism in all lands, mankind is again able to see the great historical significance of these early English soldiers of democracy, who, looking "as into a glass darkly" saw that it was not a change of rulers for which they were fighting but the end of exploitation of man by man.

The bourgeois revolution started in England in the 17th century, coming nearly one hundred and fifty years before the French Revolution. In France the struggle was fought out to a clear-cut decision, whereas in England a peculiar compromise was reached between the old feudal rulers and the rising capitalist class lasting until the Industrial Revolution. In these circumstances such revolutionary traditions as the rising of the Levellers did not retain a vivid hold on the memory of the people or inspire the proletarian movement to the extent that similar incidents have always done in France. This is all the more reason why our great revolutionary history must now be popularised among the workers, not only to counter the reactionary and distorted picture of British history favoured by Tories and many rightwing Labour leaders alike, but as an inspiration to the working class in the decisive class battles which lie ahead.

The Levellers' mutiny which culminated in the execution of their leaders in Burford churchyard in 1649 was a relatively small incident in the course of the left-wing fight for a democratic peace during the years 1647-1650. No attempt is made here to trace all the social conflicts which were being fought inside and outside the army during this period. It is hoped only to give a description of the dramatic series of incidents which led up to the final stand at Burford and convey the heroism of the men of action who took part in it.

Prologue - The Agreement of the People

The men who rose against their officers at Salisbury in the Spring of 1649 and set out on their historic march to Burford did not all regard themselves as Levellers. The title was mainly used as a term of abuse by the country squires and London merchants, just as today the word "red" or "Bolshevik" is so often used to create prejudice against militant workers.

(Note by author: There was a curious pamphlet called "Terrible and bloudy Newes from the disloyall Army in the North" with a picture on the title page of soldiers impaling babies on spears and swinging them up to dash out their brains. It proceeds to relate the terror of the inhabitants of Market Harborough when some Levellers arrived in the town on market day - they ran hither and thither in fright. But the only facts to be related when it comes to the point are that the Levellers proclaimed that there was nothing to be afraid of, "stayed awhile at the Crown and so departed peacefully". Evidently some methods of modern journalism are not new.)

Lilburn himself, the national leader of the movement repudiated the title; further, their demands did not include anything like a rough and ready redistribution of property as the term "leveller" would imply. There existed no organised working class movement as we know it, nor any form of large scale manufacture, which are the conditions in which the scientific conception of a classless society is possible. Nevertheless, most of these men were politically conscious and for several years they had been fighting for a truly democratic government. On two occasions they had joined in great armed demonstrations on a national scale, compelling Cromwell himself to concede many of their demands, at least on paper.

These gatherings had taken place about eighteen months previously at Newmarket Heath in June 1647 and at Thriplow Heath a few weeks later. The first of these was endorsed by Cromwell but the latter seemed to have been much more under the control of the rank and file and more revolutionary in its decisions. Regimental delegates or "agitators" as they were called were appointed by the rank and file and a Grand Army Council set up on which the men's representatives sat together with an equal number of officers to decide questions of policy. For some months this remained a genuinely democratic body, remarkably similar to the system of soldiers' and sailors' delegates elected throughout the armed forces during the Russian Revolution of 1917. Eventually the army council came to be dominated by the high officers and after the suppression of the Levellers it was abolished. At Thriplow Heath the vast concourse of soldiers who must have assembled there, took a solemn oath to keep what came to be known as the "Engagement" and not to disband until the liberties of England were secured. At the same time they adopted a clear-cut political programme written in stirring language and entitled "The Agreement of the People". Thus the Levellers made clear to Parliament and the people what was meant by securing the liberties of England.

This was a remarkable document originally drafted by Lilburn and his Leveller followers. A year later in 1648 it received its final form at the hands of a sub-committee consisting of an equal number of soldier delegates, high officers and parliamentary representatives. It was finally accepted in principle, though in a modified form, by Cromwell and his "Grandees" (as the high officers were called by the common soldiers). It represented the high tide of the English Revolution. It reasserted the sovereign power of the people to make and change all laws and demanded the re-election of parliament every two years. It demanded a form of universal suffrage but did not include hired labourers on the grounds that this would lead to corruption. This was due to the fact that there was no secret ballot and it was thought, therefore, that the hired labourers on farms and in the few existing small workshops would be open to pressure from their employers. It insisted on democratic control of the army and election of officers, for whom civilians would have the right to vote; complete religious toleration and the abolition of all tithes and tolls. It also called for an alteration in the laws of land tenure which would give the yeomen and tenant farmers proprietary rights over the land they tilled.

There was another important immediate issue raised at these meetings which was the subject of strongly-worded resolutions and protests to the government. This was the question of arrears in army pay. The government was trying to fob the men off with what today would be called a form of post-war credit. These credit notes were useless to most of the now impoverished yeomen, small traders and artisans returning to "Civvy Street". Many ex-servicemen were forced by poverty to sell these certificates to speculators at a fraction of their value, and Parliament itself was actually participating in this mean robbery by employing agents to buy back its own IOUs at three or four shillings in the pound. This secondary demand eventually became a focal point of all the Levellers' grievances, leading to open revolt, just as in modern times economic strikes of the working class in defence of living standards have often led to much more far reaching political revolts.

Most of the troops that marched out of "Old Sarum" (Salisbury) flying their own sea-green colours into the green countryside of an English spring in 1649 would have attended the great popular assemblies which had adopted the Agreement of the People. Those who had not would have been fully conversant with its principles as with the terms of the famous "Engagement". In the period since the first drafting of the Peoples' Agreement the leaders of the movement had written and distributed great numbers of political pamphlets and tracts to reinforce the original arguments of the agreement. The regimental agitators had followed this up with continual verbal propaganda. The Leveller's revolt was therefore a conscious, level-headed and inspired movement, typically English in its downright and practical methods of organisation; methods which the English masses have improved upon and extended through the centuries with increasing success.

An examination of various Leveller pronouncements during the risings disproves the contention of many orthodox historians that they were irreconcilable doctrinaires. The printed documents show that all their actions were the result of reasoned and careful discussion and they resorted to force only when they found themselves threatened with violence. Neither must it be thought that the Burford incident was an isolated one; mutinies on a larger scale had taken place in widely separated parts of the country. While the revolt at Salisbury was coming to a head, Cromwell with the very greatest difficulty, and by means of the most specious promises was preventing a much larger body of troops from taking similar action in London in 1647; several regiments had raised the sea-green colours at Ware and the leaders had been immediately shot. A short time before the Burford revolt, the City had witnessed a great sea-green demonstration at the funeral of a Leveller who had been shot in St. Paul's Churchyard for the part he had played in an earlier mutiny.

Those who set out on the fatal march to Burford were well aware of the price they would have to pay for failure and although traitors, spies and cowards appeared within their ranks, the degree of unity and self-discipline they maintained to the end was proof of their great spirit. That they were betrayed rather than defeated is proved by an examination of contemporary documents. If they erred, it was in being over-trusting in their dealings with representatives of the high command who applied the method of delay until they were ready to strike in overwhelming strength. It is this battle of manoeuvre, quite familiar to the industrial worker engaged in strike action, which we shall now endeavour to describe in detail.

Gathering Storm in Salisbury

At the beginning of May 1649, two cavalry regiments were stationed in Salisbury. The second Civil War was over and Cromwell's chief anxiety was what to do with these turbulent soldiers who had become infected with the revolutionary ideas of the Levellers. He decided that the most effective diversion of their militant energies would be a campaign in Ireland. This would not only divert attention from the grievances at home, but would also solve the awkward question of arrears in pay, by providing opportunities for loot and land settlement in Ireland.

At first this astute move had just the opposite effect to what had been expected. The soldiers under new and more revolutionary "agitators" (or Commissars as they might be described today) immediately invoked the famous "Engagement" not to disband their forces until they had obtained justice at home, claiming that this was a deceitful way of achieving their dispersal. It must be remembered that Cromwell himself had somewhat reluctantly endorsed the "Engagement".

The selection of the regiments to proceed to active service in Ireland was to be arrived at by a lottery organised by the high officers. The very method adopted would have looked suspicious and when the lot fell on the two regiments of Colonel Scroop and General Ireton stationed in Salisbury, the troops immediately declared this to be an infringement of the 1647 "Engagement" and refused to go. They were given the usual harangue on the parade ground, consisting of a mixture of threats and pleading, whereupon the soldiers drew up a memorandum called "A Paper of Some Reasons, by way of Declaration" and despatched this to Colonel Scroop. In this they were joined by one of the officers, a certain Cornet (sub-lieutenant) Dene who pushed himself quickly to the front as an advocate of extreme revolutionary methods, until the time of the final crisis, when he revealed himself as a type the modern working class movement has become very familiar with.

Their views having been presented to the Colonel, the troops were called to a rendezvous by the officers and were told that no-one was to be forced to go to Ireland, but that those who did not wish to go could take their discharge and leave the army at once. This sounds a simple solution, but it was in fact a cunning attempt to throw confusion into the minds of the men, for it meant that if they stayed at home all chance of getting their arrears of pay would be gone, and if they went abroad the solidarity of the rank and file would be broken and the whole movement for post-war justice would collapse. When they refused to adopt either course but acted as one body, Colonel Scroop (who seems to have been an "ultra-blimp", even in the opinion of his fellow officers) informed the men in strong terms that they were already guilty of mutiny. An ironical note is added by the fact that when the Colonel was asked whether he would go to Ireland, he replied that he himself could give no assurance that he would go.

After this Colonel Scroop's regiment at once sent a letter to the troops under General Ireton who then decided to join the original mutineers. After further threats, Colonel Scroop ordered all the horses to be placed some two miles from the men's quarters. This order the men carried out, proving that there was as yet no repudiation of discipline and that the men were still only standing on what they considered their constitutional rights and remaining true to the engagement undertaken by the whole army, including Cromwell himself. However, when it became evident that the Colonel was preparing to use force against them, the men regained their horses and began to make preparations to defend themselves if attacked. Whether the officers were actually disobeyed and driven away is not clear. The survivors of the Burford battle afterwards published a pamphlet in defence of their actions. This states that the officers themselves left the regiment, and the men then elected new officers. There seems to be some indication that the infamous Cornet Dene who joined the mutineers urged violence against his ex-colleagues. From the moment of the re-election of officers, of course, the die was cast and the whole incident may best be told in the words of some of those who survived:

"Our old solemn Engagement at Newmarket and Thriplow Heath, June 5th, 1647, with the manifold Declarations, Promises and Protestations of the Army, in pursuance thereof, were all utterly declined and most Perfidiously broken, and the whole fabric of the Commonwealth fell into the grossest and vilest tyranny that ever Englishmen groaned under… which, with the considerations of the particular, most insufferable abuses and dissatisfactions put upon us, moved us to an unanimous refusal to go… till full satisfaction and security was given to us as Soldiers and Commoners, by a Council of our own free election… Whereupon we drew up a paper of some Reasons, by way of Declaration, concerning our said refusal to deliver to our Colonel; unto which we all cheerfully subscribed, with many of our officers (especially Cornet Dene, who then seemingly was extreme forward in assisting us to effect our desires) which being delivered a day or two after, immediately our officers called a rendez-vous near under Salisbury, where they declared that the General intended not to force us, but that we might either go or stay, and so certifying our intents to stay, we were all drawn into the town again, and the Colonel together with the rest of the officers, full of discontent, threatened us the Soldiers, and because we were all, or most of one mind, he termed our unity a Combination or Mutiny, yet himself upon our request to know, told us, that he could not assure us, that he would go. Which forementioned paper, with a letter, we sent to Commissary General Ireton's Regiment, who took it so well, that they were immediately upon their march towards our quarters to joyn with us."

To Banbury to Join Forces

Having drawn up a further Declaration of Aims and despatched it to Generals Fairfax and Cromwell, the two regiments, which numbered over a thousand men, had to decide on their future tactics and strategy. This must have constituted a serious problem for the leaders. It is doubtful whether they would have known much about the threatening disturbances that were taking place among the much larger bodies of the London troops. News, which today spreads over the land in a few minutes, would have taken two or three days to reach Salisbury from London. They would know, of course that feeling was very strong and that similar movements were likely elsewhere, but that is all. Few of them would even have heard of the more thoroughgoing communist and civilian arm of the Levellers' movement, which, in that very spring of 1649, was making the first attempt to occupy land in the name of the people and cultivate it along co-operative lines. They therefore decided to strike for the town of Banbury from which they had received indisputable information that a similar mutiny to their own had taken place.

These troops, under an NCO by the name of William Thompson, were at the same time declaring their solidarity in a powerfully worded manifesto of their own. This refers to the news they had received from Salisbury in the following terms:

"We do own and avow the late proceedings in Col. Scroop's, Col. Harrison's and Major General Skippon's regiments, declared in their resolutions published in print; as one man resolving to live and dy with them in their and our just and mutual defense."

In view of this information, the leaders who constituted a regimental committee decided to make a junction with their comrades at Banbury. This would involve a stiff march across country much rougher than it is today and would include a great part of the Cotswolds, a distance of over fifty miles. Once such a junction had been made, a force of nearly three thousand cavalry would have been able to take the field. This would have made a formidable force, and using Banbury as a centre it could have reasonably expected to hold out for some time. If threatened by overwhelming forces it could have retreated into the Cotswolds.

Assuming that the leadership was made up in the main of those who were eventually executed in Burford churchyard, the Military Committee probably consisted of about six men, the most prominent of these being Cornet Dene, ex-regular officer, Cornet Thompson (brother of the Banbury leader) and Corporal Perkins and Private Church. The two latter ordinary soldiers were the most stable and courageous leaders remaining constant and incorruptible to the end, although less vociferous than the others.

On May 11th the Salisbury regiments struck across Salisbury Plain. They rode hard as they had heard that Cromwell and Fairfax were already on the move, and had reached Andover. From Andover Cromwell dispatched four officers to catch up with the mutineers. These officers were supposed to discuss terms with the mutineers, but it seems probable that they were actually dispatched for tactical reasons and that their real orders were to delay the rebels as long as possible and so give Cromwell and Fairfax time to get within striking distance. They made several attempts to involve the Levellers in long-winded discussions and, although the men were not inclined to listen to them, these contacts must have reduced the speed of the advance.

Cromwell's agents first made contact with the main body at Wantage late in the evening of May 12th. They evidently met with a rebuff but were promised an interview at Stanford in the Vale the next morning. This meeting was also abortive, apparently because the men's old Colonel, the detested Scroop suddenly appeared, and the Levellers moved on to Abingdon. Again the officers rather ignominiously trailed along behind the troops. At Abingdon the men would have no dealings with Scroop but agreed to parley with the other four officers. One of these, Major White, made a speech in which he spoke of the need for army unity to save the Commonwealth and concluded by reading a letter from Fairfax and Cromwell. This had little effect on the men who believed that it was the salvation of the Commonwealth that made their present fight necessary. Most of their national leaders, men of great courage like Lilburn and Overton, were imprisoned in the Tower of London. These men had fought in every notable battle for the Commonwealth and had given unconditional loyalty to Cromwell until the end of the Civil War. Lilburn, in particular, had distinguished himself; he had been wounded several times and risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. The soldiers now saw him as the only public man willing to fight for a genuinely democratic Commonwealth instead of a dictatorship of the high generals and the City of London merchant princes.

The Levellers had decided to proceed to Banbury via Abingdon - a most roundabout route - owing to information that the troops of Colonel Harrison would probably join their ranks near that town. They now proceeded in this direction, with Major White and two officers still following. Colonel Scotten, to use the mutineers’ own words "slipped away" to give Cromwell news of their next destination. In the pamphlet "The Levellers Vindicated" it appears that many of the men saw through these tactics, as the following extract from the original document indicates:

"Being in treatie with the commissioners, and having intelligence that the General and the Lt. General were upon their march towards us, many of us several times urged to Major White that he came to betray us, to which he replyed, that the General and the Lt. General had engaged their honours not to engage us in any Hostile manner till they had received our answer… We gave the more credit to them who seemed extreme forward and hastie to make the composeure, pretending so far to improve of our standing for the things contained in our arrangement at Triplo-Heath, that himself with our consents drew up a Paper or Answer to the General for us… During this time of treatie while the commissioners thus assured us all security, one of them, the Colonel Scotten privately slips from us, and two others, Captains Bayley and Peverill, left notes at every town of our strength and condition…"

Had Major White and his talkative officers been sent packing after the first contact, it is very doubtful whether Cromwell could have destroyed the Levellers by his final surprise attack at Burford. The success of his plan clearly depended on precise information as to the position of the mutineers. It is true that his travelling speed of forty or fifty miles a day was remarkable, but it was the exact knowledge of the point reached by the Levellers, that enabled him to catch them at Burford with a large body of troops.

In spite of Major White's protestations spoken at the time and put in writing later, it is obvious that he created an effective intelligence service under the guise of being an emissary to discuss honourable terms.

Treachery at Burford

Just outside Abingdon the expected meeting with Colonel Harrison's troops took place. Delegates were sent by the Salisbury regiments, who read out their declaration. This was favourably received by Harrison's men who stated that they were marching to quarters at Thame, and in the morning would communicate their decision. Before the two bodies separated, however, the first brush with some of Fairfax's reconnaissance troops took place, which thanks to Major White, must have still further delayed progress to Banbury. These hostile troops ‑ not more than a hundred in number ‑ placed themselves astride a bridge at Newbridge. These troops could have been routed probably without loss of life, but Major White persuaded the Levellers not to force a crossing, pleading that they should not be the first to shed blood in a new war. As a result the Salisbury men withdrew and were compelled to ford the river at another point a considerable distance away ‑ a difficult and delaying operation.

It was now growing late on Sunday May 13th. The troops had already travelled from Wantage; they were tired and wet after fording the river. The question of quarters for the night was becoming an urgent problem. The decision was left to Lieutenant Ray and ‑ Cornet Dene, who decided to proceed a further fifteen miles to Burford. This would have appeared satisfactory to the men, as being well on the way to their comrades at Banbury. Further, Burford had a solidly parliament reputation during the Civil War. It was a centre of the wool clothing industry and the population would probably be sympathetic. From this town had come Lenthall, the speaker of the House of Commons, which had resisted the King when he had attempted to impose his will on Parliament on the eve of the Civil War.

Some time after dark, fifteen hundred grim and exhausted Leveller horsemen entered Burford and proceeded to find suitable quarters and billets for a night's sleep. The little grey-stoned Cotswold town was not large enough to shelter so large a body of men and many had to go to surrounding villages. Arrangements were unfortunately left in the hands of Cornet Dene who appointed a fellow traitor, Quartermaster Moore to organise the guard. This he did in a very casual way, and then, pretending to be going for refreshments left the town, returning some hours later at the head of the General's forces to strike down his ex-comrades.