Zimbabwe: Despite Mugabe's opportunism, radical land reform is necessary

By Grasian Mkodzongi

March 11, 2010 – Pambazuka News – Zimbabwe’s land issue has generated unprecedented debates both within and outside the country. The debates, which followed the dramatic occupations of white farms by rural peasants in the late 1990s, are generally polarised between those who support radical land reform and those who support market-orientated reforms. The former stand accused of supporting Mugabe’s regime while the latter are generally maligned as neo-colonialists running a smear campaign against the ruling Zimbabwe AFrican National Union-Patriotic Frent (ZANU-PF).

An unfortunate outcome of these polarities has been the trivialisation of the land issue; land occupations have been depicted as simple acts of political gimmickry; landless peasants who occupied these farms have been branded as agents of agrarian and environmental destruction, and are often considered to be in service to the "evil" regime of Robert Mugabe. Some academics have even gone as far as branding the whole process of land occupations, and the violence associated with it, as an apocalyptic end of modernity.

In academia, supporters of radical land reform are generally in the minority; this has made it extremely difficult to challenge the current neoliberal orthodoxy, which dominates land and agrarian reform policy making in many African countries. The few scholars, who have openly challenged the "hostile" neoliberal approach to argue for radical land reform, including Sam Moyo, Paris Yeros and Mamood Mamdani, have often been accused of colluding with Mugabe’s undemocratic regime.

Post-independence: white commercial farmers, black elite prosper

That Mugabe opportunistically used the land issue to boost his political legitimacy is an undeniable fact. Indeed, the country’s collective memory was conveniently manipulated to fit a set political agenda under guise of the "Third Chimurenga" project. However, juxtaposed to Mugabe’s gerrymandering and manipulation of historical memory is a reality that many critics of Mugabe have so far failed to address. How can one justify the continued existence of a dualistic land ownership structure decades after independence, in a country whose struggle for liberation crystallised around the land issue? How could such an unjust and medieval property ownership structure be permanently sustained in a country where 60 per cent of the population depends on land for their livelihoods?

Another paradox of Zimbabwe’s independence is the extent to which white farmers emerged unscathed by the raging fires of the liberation struggle. Zimbabwe’s negotiated settlement, which led to independence in 1980, left white farmers constitutionally protected. Like Royal game, they held the entire nation at ransom thanks to Lord Carrington, who secured their private property and political rights before handing over a poisoned state to the blacks. Mugabe’s reconciliatory rhetoric that dominated the early years of independence led to the general belief among white Rhodesians that independence was "business as usual", with many whites continuing to enjoy colonial era privileges and existing in white enclaves.

In the so-called "new Zimbabwe", white commercial farmers continued to dominate the commercial farming sector, a key strategic sector given the largely agrarian nature of Zimbabwe’s economy. This gave them leverage over government policy, which they used to secure their large estates from potential forceful acquisition. Above all, they voted for Ian Smith’s exclusively white Rhodesian Front political party; a mockery of the ideals of a "united nation" propounded by Mugabe’s nationalist administration.

On the other hand, the peasantry in remote rural locations continued to eke out a living on degraded patches of barren land, waiting for the "promised" land that was at the core of the liberation struggle. However, such promises failed to materialise; macroeconomic policies favoured landed capitalists and black elites based in cities that generally enjoyed the patronage of senior politicians. A result of the above was that most of the land "recovered" by the government was diverted to ZANU-PF loyalists through patronage networks.

Why then do many people decry the land invasions if history shows that peasants were the major losers at independence? Given Zimbabwe’s history, one wonders why white farmers were allowed to sell land back to the government after 1980 instead of helping to contribute to the land reform program as a form of reparations for the violence and plunder suffered by many Africans during the colonial era. After all, most of the large farms were acquired under unjust and illegal terms.

Justice would have been better served if after securing independence, Mugabe’s government had thrown away the 1979 Lancaster House Constitution in favour of a just constitution based on the country’s historical experiences. Why hang on to a constitution, which promoted the interests of the very people that supported the wanton destruction of African livelihoods, and the merciless bombing of civilians at Nyadzonya, which to this day have never been fully accounted for. This would have allowed an unfettered land reform program that was cognisant of our past and righted the wrongful misdeeds of a few.

Instead, a dithering elitist government failed to deliver one of the most precious prizes of our independence: the land. For if so many people died at Chimoio, Nyadzonya and in many operational zones, how could their souls rest in peace if independence only resulted in the perpetuation of the status quo? Why could we as a sovereign nation in the interest of morality and justice not say to Britain and other world nations that so many people died for this land, all they want is a fair share of their heritage?’ Is that not a modest demand given our history?

Mugabe’s rhetoric on land should be given serious consideration, however he should also be held accountable for failing to stand up against neocolonial tactics that led to unnecessary delays in recovering stolen property and for presiding over a patrimonial system which helped to marginalise a large section of the population. Much of the socialist rhetoric that appears in the country’s Transitional Development Plan (TDP) was never put into practice, instead an ahistorical Land Reform and Resettlement Programme (LRRP) was adopted. This policy, much influenced by Britain and other agents of Western capitalism, left too much leverage with white farmers who were able to dictate the pace of the land reform program, and in the process, distort land markets to their advantage.

The result was that the LRRP was too expensive to sustain for a postcolonial government with limited resources. Moreover, those who were "chosen" for resettlement were given land unfavorable to agriculture with limited support in terms of infrastructure and farming inputs. Mugabe’s government, like its colonial predecessor, was reluctant to extend full property rights to the beneficiaries of the LRRP and instead opted to allow resettled farmers to occupy land under insecure permits while at the same time allowing white farmers to continue owning their land on a more secure freehold basis. This perpetuated a system of insecure property rights in communal areas that had been created during the colonial era within the so-called "communal tenure" system.

History ignored

An analysis of the arguments against radical land reform reveals a chronic failure by both journalists and academics to provide a balanced overview of the Zimbabwean land issue; the causal factors of landlessness steeped in the country’s history are often ignored. There is a tendency to confuse the land issue with Mugabe’s political expediency and in the process the baby is thrown away with the bath water. The genuine need for land, which is reflected in many rural areas across the country, is simply dismissed as Mugabe’s political posturing.

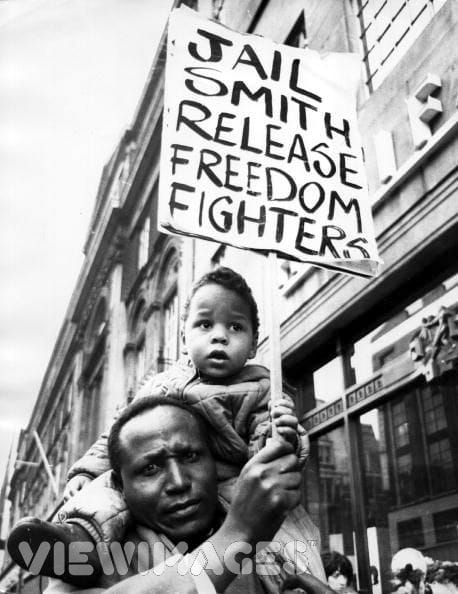

What is often forgotten is that not very long ago millions of Africans were deliberately disenfranchised by a system of state-managed repression, segregation and violence. It is these masses who sacrificed their lives and livelihoods to liberate the country and it is these masses who have the moral right to claim back their land. This legitimate need to right the historical wrongs should never be confused with ZANU-PF’s attempts to manipulate history for its own selfish interests.

What is also deeply disturbing about those who have argued against land invasions is their total disregard for the views of the poor and marginalised peasants who invaded these farms. On the rare occasions when peasants are featured in short documentaries or academic articles, they are often depicted as barbaric savages attacking white farmers and ruining productive farms. In contrast, white farmers have generally been given positive media coverage in the West – sentimental testimonials telling stories of loss and ruin, agricultural equipment destroyed and wildlife poached. These stories are often accompanied by graphic images of dead wild animals, especially endangered species like rhinos and elephants.

This "sadistic" imagery has generated sympathy for white farmers, by portraying them as hard-working people who became victims of Robert Mugabe’s "evil regime". The plight of many rural farmers who have struggled to survive since the country was liberated decades ago is generally overlooked. They have no one to tell their stories of survival to, and local "native" intellectuals, generally far removed from the village, have failed to inform the world about the peasants' precarious existence: landlessness, water shortages and disease.

Black peasantry misrepresented

What is often suggested in the studies of fly-past researchers is the notion that black peasants have an inherent lack of basic environmental knowledge and that they are incapable of feeding themselves. Across Europe, ignorance about the historical background to Zimbabwe’s land issue among ordinary people runs deep; remarks about how the Zimbabwe government allowed unskilled rural farmers to occupy farms are commonplace. The current food shortages facing the country are simply blamed on incompetent peasants taking over white farms.

It has become fashionable to project Zimbabwe as "a bread basket" before the land invasions and a "basket case" after land invasions. This has helped to support the assumption that without white farmers the country could not feed itself. What is often not mentioned is that the white farmer in Africa is generally an administrator; he does not physically grow crops himself. His black troops produce on his behalf. However he gets the lion’s share of the profits because he controls the means of production.

Moreover, it is easily forgotten that in the early years of colonial occupation in the 1890s, European settlers in Rhodesia survived on grain produced by Africans until The British South Africa Company (BSAC) deliberately destroyed a booming African agriculture in favour of promoting European agriculture after the so called "gold rush" proved to be largely false. Against all odds, Africans have been feeding themselves even during the depression years of the 1930s when the colonial government introduced the Maize Control Act, which helped to distort the grain market in order to protect European farmers.

Apart from the above, there is another argument based on neoliberal thinking, which says that land reform was supposed to be carried out in an orderly way in order to harness "white skills". This, it is argued, would protect the productive potential of these farms. The question is why didn’t these white farmers share their skills before the onset of the land invasions? How can one account for the poverty and dislocation of many farm workers who lost their livelihoods once a farmer decided they were no longer needed after many years of hard labour with minimum remuneration?

This argument is also based on a false assumption that black farmers cannot grow crops without white supervision. Most large-scale commercial farms have historically relied on black labour. If large-scale commercial farms are largely run by black workers who with time have acquired advanced technical skills to operate farm machinery, supervise the large-scale growing of commercial crops including tobacco and wheat, why then can blacks fail to do the same for themselves if given the land and the support required to run successful agricultural enterprises?

The image of the black farmer as a permanent subsistence farmer has become part of the official discourse about land and agrarian reform simply because for many decades black farmers have not been given the chance to invest in productive agriculture. It’s a historical fact that white agricultural success was based on expensive state subsidies, access to cheap labour and extension services, which allowed them to make profits even during the difficult years of economic stagnation. Such services were not accessible to black farmers, who had to make do with very little financial and technical support from central government.

While it is true that land invasions did impact on agricultural production; critics of the program have based their arguments on emotions rather than facts. Since the land invasions took place, no significant longitudinal study based on empirical research has been carried out to justify these arguments. Nobody knows to what extent the land invasions have impacted on agricultural production across the country. Moreover in trying to access such impacts, one has to take into account climatic factors like recurring droughts, which have historically affected agricultural production.

Simplistic arguments biased against the peasantry have led to the trivialisation of an issue that is of paramount importance to Zimbabwe culturally, historically and economically. For land is not only the resource we have in abundance, it’s the only resource that sustains three-quarters of the Zimbabwean population.

Given the above, land invasions were inevitable and necessary to ensure peasants "got a piece of the cake". Of course one cannot expect such a radical program to take place without any form of disruption. While it’s painful in the short term, land invasions have helped a significant number of propertyless peasants to not only recover land, but to enjoy a sense of restitution which has a healing effect given the country’s tortured history. They also helped to break the monopoly of white farmers in commercial agriculture by opening up this key sector to black farmers. Moreover recent research by World Bank economists has proven that large commercial farms are not very productive compared to family-operated smallholder farms; they are also a source of political instability as our recent history has demonstrated. Breaking up large commercial farms in favour of more efficient smallholder entities makes economic sense and promotes political stability.

Full property rights for peasants

What the Zimbabwean government should do now is to stop dilly-dallying and extend full property rights to peasants settled under the A1 Scheme to provide security and incentives for agricultural investment. It should also offer financial and technical support for those farmers who want to venture into commercial farming. Such a process requires non-partisan support from all those who benefited from land reform. It also requires a mechanism to recover land from those who are hoarding unproductive farms. This could be achieved through a land audit and a policy restricting farm ownership to a "one person one farm" basis.

If the above measures were implemented, Zimbabwe would lead the way as the only country in postcolonial Africa to implement the most radical transfer of property in the 21st century. It would set an example for Zimbabwe’s neighbours, South Africa and Namibia, which are still slumbering under the stupor of market-driven land reform, with the inevitable risk of political instability as marginalised peasants are likely to resort to violence to recover land.

[Grasian Mkodzongi is an ecologist and PhD candidate at the Centre of African Studies (University of Edinburgh.This article first appeared at Pambazuka News.]

Mugabe, the land baron

Zimbabwean president is now one of the country's biggest landowners

http://www.zimbabwemetro.com/headline/mugabe-is-largest-landowner-in-zimbabwe/

Apr 25, 2010 12:00 AM | By Own correspondent

President Robert Mugabe is one of the biggest landowners in Zimbabwe. A Sunday Times investigation has found that he and his family own at least

10 farms through Gushungo Holdings (Pvt) Ltd.

quote Grace's farm managers arrived without warning at 7am, and told him to cease farming and move out quote

Gushungo is Mugabe's clan name.

The company owns 10601ha of fertile land in the country's northern regions.

The Commercial Farmers' Union says that of the original 4500 large-scale white commercial farms, only 300 remain.

Mugabe and his family acquired a significant chunk of that farmland.

In 2008 - eight years after the land reform programme started - Mugabe's wife, Grace, grabbed Gwina Farm in Banket from high court Judge Ben Hlatshwayo.

He tried to fight her in the courts, but withdrew under intense political pressure - not before he had exposed Mugabe and his family as multiple farm- owners, in violation of government policy.

He revealed that the family, through Gushungo Holdings, owned Mazowe, Sigaro, Leverdale and Bassiville farms.

He eventually lost Gwina Farm to Grace Mugabe in dramatic fashion. He was forced out and promised another farm in an estate owned by the state-run Agricultural and Rural Development Authority, Transau, in Mutare.

When that failed to materialise, he moved into Kent Estate, in Norton, on land owned by Ariston Holdings.

Before being thrown out by Grace, he filed a high court application suing Gushungo Holdings - which Grace used for the takeover - and former state security minister Didymus Mutasa, who was then also minister of lands. Mutasa is now presidential affairs minister in the president's office.

In his court application, signed on November 6 2008, Judge Hlatshwayo, a Harvard University-trained lawyer and former lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe, said Grace's actions were illegal and the court should stop her.

"I have been in quiet, undisturbed, peaceful possession, occupation and production at Gwina Farm from December 2002 until October 19 2008," he said.

He said Grace's farm managers arrived without warning on Sunday October

19 at 7am, and told him to cease farming and move out.

Before leaving, they said he would get further details from Mutasa or senior ministry officials.

He immediately contacted his superiors, Chief Justice Godfrey Chidyausiku and justice minister Patrick Chinamasa, who said he should find out more because it could have been the "work of conmen".

When he got in touch with Mutasa, his worst fears were confirmed: Grace Mugabe wanted the farm.

Grace began to put more pressure on him, sending her farmworkers to measure and peg his land.

In the end, he was forced to withdraw his court application, and Grace got her way, adding one more property to Gushungo Holdings' growing list of farms.

Commercial Farmers' Union officials say Mugabe's family owns even more farms. These include the 1000ha Foyle Farm, grabbed from Ian Webster.

It was renamed Gushungo Dairy and was recently involved in a dispute with Swiss company Nestlé over a milk deal.

The family also owns the 1046ha Iron Mask Farm, taken from John Matthews by Grace under the pretext of establishing an orphanage.

Judge Hlatshwayo is not the only black farmer who has lost out to the Mugabes.

Standard Bank CEO Washington Matsaire lost his 1200ha Gwebi Wood Farm to them.

The Mugabes also grabbed 1488ha Leverdale Farm from Piers Nicolle.

Mugabe's personal farm, Highfield, in Norton, is 445ha.

Farmers in the area say all nearby farms were taken to create a ''security buffer zone" for the president, leaving him effectively controlling 4050ha.

Mugabe and allies own 40% of seized land

www.mg.co.za

Mugabe and allies own 40% of seized land

Dec 01 2010

Zimbabwe's president, Robert Mugabe, and his allies have seized nearly half the country's commercial farms in a land grab widely blamed for economic collapse, an investigation claims today.

Mugabe has bought the loyalty of Cabinet ministers, senior army and government officials and judges with nearly five million hectares of agricultural land, including wildlife conservancies and plantations, according to the national news agency ZimOnline.

The 86-year-old president and his wife, Grace, are said to own 14 farms spanning at least 16 000 hectares.

ZimOnline's investigation undermined the central claim behind Mugabe's land reforms: that they are give the majority of black Zimbabweans their rightful inheritance. "Even though Mugabe has consistently maintained that his land reform programme is meant to benefit the poor black masses, it is him and his cronies who have got the most out of it," it argued.

A "new, well-connected black elite" of about 2 200 people controls nearly 40% of the 14-million hectares seized from white farmers, ZimOnline found. These range in size from 250 to 4 000 hectares in "the most fertile farming regions in the country".

The past decade of land invasions -- which reduced 4 000 white farmers to 400 by murders, beatings and forced evictions -- is held responsible by many for the demise of the "breadbasket of Africa".

ZimOnline said government documents and audit reports showed the biggest beneficiaries of land reform were "Zanu-PF members and supporters, security service chiefs and officers and traditional chiefs who have openly sided with Mugabe and senior government officials and judges."

It said all ministers and deputy ministers in Mugabe's Zanu-PF party were multiple farm owners. These include his deputy, Joice Mujuru, and her husband, the former army general Solomon Mujuru, and their relatives, who own at least 25 farms totalling 105 000 hectares.

All Zanu-PF's 56 politburo members, 98 members of parliament and 35 elected and unelected senators were allegedly allocated farms, and all

10 provincial governors have seized them, with four being multiple owners. Sixteen supreme court and high court judges also own farms.

The report said: "Of the nearly 200 officers from the rank of major to the lieutenant general in the Zimbabwe national army, 90% have farms in the most fertile parts of the country. This is replicated in the Zimbabwe republic police, Zimbabwe prisons service, air force of Zimbabwe and CIO [Central Intelligence Organisation].

'Lusted for white blood' "Constantine Chiwenga, the Zimbabwe defence forces commander, who is among a cabal of defence chiefs who have publicly declared that they will only serve Mugabe, has two farms near Harare, including the 1

200-hectare Chakoma Estates, which his wife seized at gunpoint, telling a terrified white farmer that she lusted for white blood and sought the slightest excuse to kill him."

Mugabe has billed the land reforms as a black empowerment corrective to the injustices of colonialism, which left Zimbabwe's land in the hands of a tiny white minority. A recent study challenged the prevailing view that the programme had been "all bad" for ordinary citizens.

But ZimOnline said that while at least 150 000 people may have had access to farms, the majority owned between 10 and 50 hectares and were Zanu-PF members.

"Critics who have consistently dismissed Zimbabwe's emotional land reforms as a political patronage programme by the octogenarian Mugabe to reward supporters who have kept him in power are right after all," it said.

ZimOnline noted that Zimbabwe's agricultural production had fallen by

60% since 2000 when the land invasions began. Exports from the sector fell from $1,4-billion in 2000 to nearly $700-million last year, after dipping below $500-million in 2007. ZimOnline said many farms were "lying fallow either because the new owners are not that keen on farming or they simply abandoned the properties for new farms".

Zanu-PF rejected the charge. Herbert Murerwa, the lands and rural resettlement minister, was quoted as saying: "The fact that a handful of people may have more than one farm does not detract from the overwhelming success of the land reform where the government has created

300 000 farmers over the last 10 years."

The Commercial Farmers' Union of Zimbabwe said today it was not surprised by the findings. Dean Theron, its president, said: "We are the ones it's been happening to. We know the colonial history and are not opposed to land reform, but we feel very sad at the way it has taken place. The beneficiaries are not the intended ones. The farms have been dished out to people with connections."

Eddie Cross, policy coordinator general for the Movement for Democratic Change and an agricultural economist, said: "It explains why Mugabe is so keen to avoid a land audit, and it certainly confirms everybody's feeling that there's a relatively small number of people in the land invasions and they're Zanu-PF acolytes. The only surprise is that it has taken so long to come out."

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2010