The end of pretenses: Trump’s assault on Venezuela

First published at Tempest.

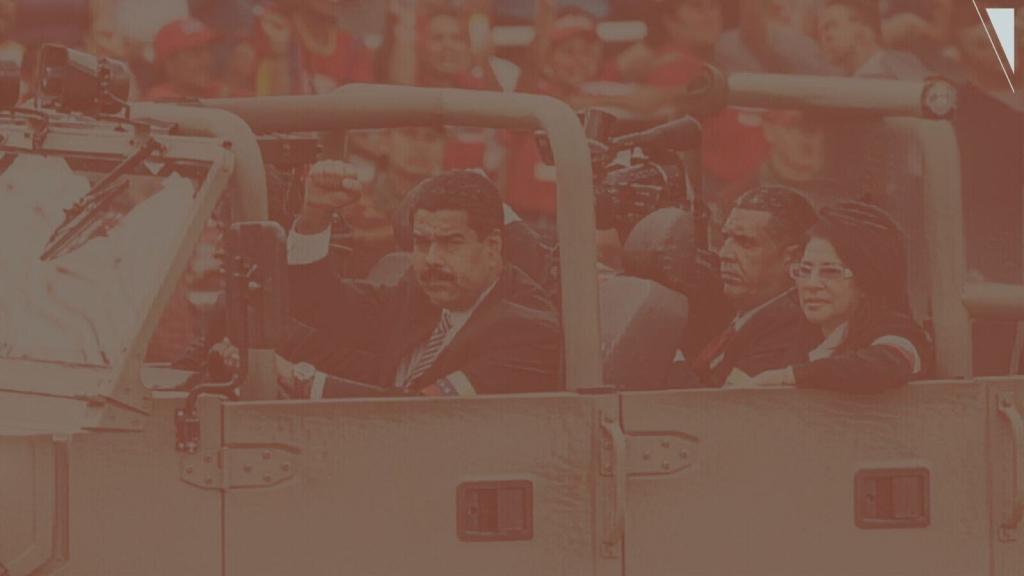

On January 3, 2026, the United States carried out a direct military operation against Venezuela. U.S. forces bombed targets in and around Caracas, struck the electrical grid, killed over one hundred people, and abducted Venezuela’s sitting president, Nicolás Maduro, along with his wife, Cilia Flores.

Within hours, President Donald Trump declared that the United States would “run” Venezuela until a “safe transition” was completed. United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio underscored the regional warning: “If I lived in Havana… I would be worried.” Trump threatened other countries, too — Colombia and Mexico included — showing again that this wasn’t about democracy. It was about submission.

The operation was presented to the world as something far smaller than what it was. Rubio called it a “police action.” Trump described it as a “counter-narcotics” operation. Others invoked democracy and the rule of law. But in Trump’s own post-invasion press conference, the word democracy did not appear even once.

What took place that day was not law enforcement. It was not drug interdiction. And it had nothing to do with democracy. It was the forcible removal of a head of state by the world’s most powerful military and the imposition of a new political order under U.S. control.

January 3 marked the culmination of a months-long campaign of pressure and intimidation that began at sea, escalated through economic coercion and acts of piracy, and ended with bombs over Caracas and the abduction of a head of state.

But it also marked something larger than Venezuela. It signaled a new phase of U.S. imperial assertion — one defined by openly seizing political authority, imposing neocolonial tutelage, and discarding international law whenever it obstructs Washington’s goals. In effect, it was the moment when even the pretense of a “rules-based order” was abandoned.

The Caribbean prelude

Throughout late 2025, the United States carried out a wave of attacks on boats in the southern Caribbean near Venezuela under the pretext of “fighting drug trafficking.” This was not standard interdiction. Instead of boarding vessels and making arrests, the U.S. shifted to militarized punishment — destroying boats, killing people from the air, and doing so as a public spectacle.

By late December, dozens of strikes had killed roughly a hundred people at sea, without transparent evidence, judicial oversight, or even clear identification of who the victims were or what they were allegedly transporting. Rubio openly boasted about the new doctrine: Instead of interdicting, “on the president’s orders, we blew it up.” Trump framed it explicitly as intimidation: “When they watch that tape, they’re going to say, ‘let’s not do this.’” The point was not law enforcement but precedent — asserting the right to summarily execute civilians from the air, outside any declared war, based solely on U.S. unilateral claims.

The pretext itself was paper-thin. Most cocaine trafficking to the United States runs through the Pacific, not the Caribbean, and fentanyl overwhelmingly enters through Mexico. Venezuela has historically been a transit country, not a major producer. Even if corruption and criminal networks exist, the leap from “drug trafficking exists” to “we bomb boats and kill people” is the real story. Here, drug trafficking functions as a floating signifier — like “terrorism” or “weapons of mass destruction” — a justification that can be invoked whenever empire wants to authorize unlimited violence.

This maritime campaign was paired with economic coercion and pressure around oil. In late 2025, the U.S. seized Venezuelan crude and imposed a blockade logic on sanctioned tankers. Asked what would happen to the seized oil, Trump replied casually, “we keep it, I guess.” That was not enforcement; it was international piracy — outright theft dressed up as law.

Together, these measures created the conditions for January 3: a pre-war configuration of military encirclement, economic strangulation, intelligence pressure, and psychological warfare.

This escalation did not follow a straight line from sanctions to bombs. There was also a period of rapprochement, and Nicolás Maduro was more than willing to collaborate.

In January 2025, Trump’s envoy arrived in Caracas and reached an agreement: Venezuela would release several U.S. prisoners and accept migrants deported from the United States. Maduro actively participated in Trump’s deportation policy, sending Conviasa — Venezuela’s national airline — into U.S. territory to pick up deported Venezuelans. He spoke publicly of a “new beginning” in relations between the two countries.

The reason for this goodwill was simple. Maduro’s priority was sanctions relief, preserving an oil-export lifeline, and above all staying in power. He wanted breathing room and access to revenue. And he signaled, repeatedly, that he was willing to make far-reaching concessions to get it.

As negotiations continued through 2025 — especially in the months leading up to October — those offers became more extreme. Maduro proposed giving the Trump administration a dominant stake in Venezuela’s oil and mineral wealth: majority ownership, decisive control over boards, budgets, and strategy, and the ability to overrule the Venezuelan state itself. This represented a qualitative escalation in Maduro’s long break with Chávez’s resource nationalism and with constitutional requirements that PDVSA retain majority control. In plain terms, it was neocolonial — and it cannot be described as anti-imperialist in any meaningful sense.

Maduro also offered to open existing and future oil and gold projects to U.S. corporations, grant preferential contracts, reverse oil exports from China to the United States, and slash contracts with Chinese, Iranian, and Russian firms. That was not resistance. It was alignment — offered from Caracas.

One of the bitter ironies of this moment is that once Maduro made these offers, his program became increasingly indistinguishable from María Corina Machado’s long-standing “open door” agenda, which has always promised Venezuela’s resources to foreign capital under aggressive neoliberal terms.

From rapprochement to aggression

If Maduro was willing to negotiate and was offering all these concessions then why did it still end in bombs and abduction? Because Trump’s strategy in Venezuela was never simply transactional. It was hegemonic crisis management—an effort to reassert U.S. hemispheric dominance under conditions of decline and to use Venezuela as a demonstration case for the region, especially to discipline states that hedge with China, Russia, or Iran.

That is why the operation was designed as spectacle. It was not enough to extract concessions quietly. Power had to be staged: the ability to strike a sovereign country, remove its president in under ninety minutes, and send a message to the hemisphere that, as the U.S. ambassador to the UN put it, “This is our hemisphere.” It was the Monroe Doctrine relaunched through raw force.

At a moment when U.S. consent-based hegemony is eroding, Venezuela represented an unacceptable breach: the world’s largest proven oil reserves, aligned with U.S. rivals, and increasingly integrated into alternative circuits of trade and finance. After the coup, Washington made its priorities explicit — privileged access for U.S. corporations, the severing of relations with designated adversaries, and the reorientation of Venezuela’s political economy back into the U.S. orbit.

This is why January 3 cannot be understood as a narrow oil grab. It is part of a broader imperial struggle over markets, raw materials, trade routes, and spheres of influence amid an intensifying crisis of global capitalism. The November 2025 National Security Strategy states this openly: the United States will “reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine” and deny non-hemispheric competitors’ control over strategic assets in the hemisphere. Venezuela — cheap labor, dismantled regulations, abundant resources, and a shattered social fabric — is treated as both a warning and an opportunity: a place to expel rival powers and re-impose, by force if necessary, imperial order.

Inside Venezuela

The internal Venezuelan story explains why this was so easy.

It was so easy because the Bolivarian process had been hollowed out — politically, socially, and materially — by Maduro’s authoritarian, anti-worker, neoliberal turn. For more than a decade, Venezuela has endured economic collapse and social devastation. Wages were pulverized, public services collapsed, and millions were forced to migrate. The minimum wage fell to starvation levels — less than one U.S. dollar a month — pushing survival onto remittances, informal work, and discretionary government bonuses.

Repression deepened as well: against trade unionists, human rights defenders, left critics, community organizers, and workers fighting for constitutional rights. Maduro jailed oil workers and union leaders, disciplining labor to attract capital while cloaking the project in socialist language. Through instruments like the 2020 Anti-Blockade Law, the government signed secret contracts, privatized behind closed doors, and bypassed democratic oversight in violation of constitutional requirements.

Two consequences followed. First, anti-imperialist sentiment was fractured. Under Chávez, an external assault would have triggered mass mobilization. Under Maduro, anti-imperialism became precarious because the regime itself had exhausted and betrayed its social base. In a battered society, many people became demoralized or even tempted by the illusion that U.S. intervention might offer an escape. That illusion is tragic — but it was produced by years of immiseration and repression.

Second, the state itself became more compatible with neocolonial tutelage. A regime that already governs through secret deals, neoliberal openings, and labor repression is more structurally capable of conceding to imperial power, because its core project is no longer popular emancipation but regime survival and capitalist accumulation under authoritarian rule.

When the U.S. attacked, the regime’s “anti-imperialism” collapsed into what it largely had become — a rhetorical shell covering an apparatus ready to negotiate its own continuation.

Why Delcy Rodríguez and not María Corina Machado?

That regional warning, and the open declaration of U.S. tutelage over Venezuela, immediately raised a question many expected to have an obvious answer: Why wasn’t María Corina Machado installed, Trump’s longtime ally and the loudest advocate of U.S. intervention, but instead Delcy Rodríguez, Maduro’s own vice president and a pillar of Maduro’s party, the PSUV?

María Corina Machado was not installed because Trump wanted stability without occupation. She does not control the state or the military, which remains tied to Chavismo and Madurismo. Installing her would risk fracture, civil conflict and chaos — and chaos would require U.S. troops, potentially tens of thousands. This is precisely what Trump wants to avoid.

Rodríguez, by contrast, offered administrative continuity. The PSUV apparatus stayed intact. The same coercive institutions remained, and that apparatus can be kept in place under duress. The governing elite knows what Washington is willing to do. The threat of escalation becomes permanent leverage.

In short, Rodríguez can deliver compliance stripped of symbolism. Maduro was a demonized figure in U.S. politics, but also — however hollowly — a symbol of anti-imperial defiance. Any deal with him looks like bargaining with an adversary. He also had to perform sovereignty, to maintain even a thin nationalist posture as part of regime legitimacy.

Rodríguez can offer the same concessions without the baggage. And she can do it under the shadow of a protectorate-like arrangement. She can call it “cooperation,” “dialogue,” “shared development.” She can normalize tutelage. She can make a neocolonial arrangement appear like a transition.

Collusion?

This raises unavoidable question of collusion or negotiated surrender. The speed of the operation, the minimal resistance, the failure to release transparent casualty reports immediately, the choice to recognize Rodríguez rather than Machado and the apparent readiness of the remaining leadership to continue governing all suggest that sectors of the ruling elite were willing to sacrifice Maduro to preserve the structure of power.

Rodríguez initially demanded Maduro’s liberation and used some revolutionary symbolism — but she quickly shifted tone toward “collaboration and dialogue” with the United States, and toward restoring “normal activities,” not mobilizing resistance. Increased military and police presence appeared, but not mass popular defense. The regime’s priority seemed to be stability and continuation — not sovereignty or resistance.

What remains is Madurismo without Maduro: an authoritarian apparatus administering U.S. demands under duress — a neocolonial state in practice if not in name.

Was this attack legal?

Legally, the operation was a clear act of aggression. Under the UN Charter, states may not use force against another country’s territorial integrity or political independence except in self-defense against an armed attack or with Security Council authorization. Neither existed here. Trump’s own words—“we will run Venezuela”—made clear that this was not an “arrest operation” or law enforcement but imperial rule.

But it is important to remember, as Egyptian journalist Omar El Akkad tells us:

In the end there is no international rules-based order, no universal human rights, no equal justice for all, simply fleeting arrangements of convenience in which any amount of human collateral is deemed acceptable so long as it works in the empire’s interest.

That is the world January 3 belongs to.

Tasks for the left

The task for the left is not to choose between imperial tutelage and authoritarian neoliberalism. It is to defend sovereignty while building an independent, working-class, democratic alternative — breaking with imperial capital, ending secret privatizations, restoring rights, freeing political prisoners, rebuilding unions, and restoring wages.

Maduro’s anti-worker neoliberalism did not protect Venezuela from imperialism; it weakened it. By hollowing out the Bolivarian process, the regime dismantled the very social forces capable of defending sovereignty from below, making Venezuela easier to discipline and easier to subordinate.

January 3 was the collision of U.S. imperial escalation with Venezuela’s internal exhaustion, an exhaustion produced by years of austerity, repression, and a regime that abandoned popular emancipation long ago.

What comes next remains uncertain. What is already clear is that Venezuela is being used as a demonstration case for the hemisphere — and resisting this is not only about Venezuela, but about refusing the normalization of a new imperial era in which sovereignty is discarded, and power is exercised openly and without pretense.

Anderson Bean is a North Carolina–based activist and editor and contributor of the book Venezuela in Crisis: Socialist Perspectives from Haymarket Books, and the author of Communes and the Venezuelan State: The Struggle for Participatory Democracy in a Time of Crisis from Lexington Books.