The House That Jack Built: Jack Mundey, Green Bans Hero

By James Colman

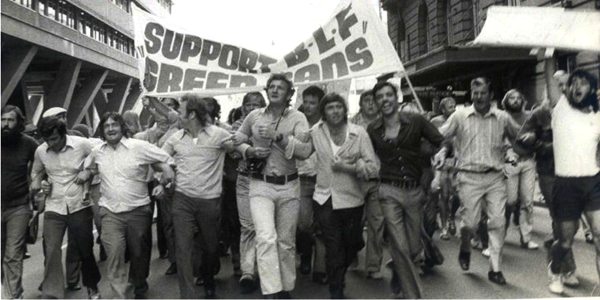

NewSouth Publishing, 2016, 356 pages Reviewed by Phil Shannon Pavlovian hostility to construction industry unions and venom-flecked hatred of the environment movement is far from a new development amongst conservative commentators, notes James Colman (Sydney architect, urban planner and university lecturer) in his book, The House That Jack Built, on Jack Mundey, the 1970s New South Wales State Secretary of the Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF) who originated the world’s first ‘green bans’ to save working class housing, historic buildings and urban bushland from the developers’ bulldozer. Colman cites the Daily Telegraph’s Miranda Devine, for example, who could simply cut-and-paste her comments (the “disgraced” BLF’s “stand-over tactics”, “intimidation”, “greed, thuggery and graft”) from four decades ago into her jeremiads against Australia’s current construction union. The object of Devine’s wrath back then was a Queensland dairy farm boy and apprentice plumber who moved to Sydney in 1950 to play first-grade rugby league for Parramatta before finding work in the construction and demolition industry where Mundey joined the Communist Party of Australia as, in his words, “a militant worker who judged communists … as people who wanted to make life better for ordinary workers”. Elected as BLF leader during a building boom, union militancy, wages and working conditions flourished under Mundey’s guidance. While his Marxism informed the traditional industrial struggle around the means of production, Mundey’s embrace of the new social movements also meant that the ends of production mattered, too. If “development” meant the destruction of city green space, working class homes and colonial-era buildings to make way for towering luxury high-rise apartment complexes, plush hotels, identikit malls and “lifeless citadels of commerce”, then Mundey’s builders labourers would try to thwart it. If residents’ pleas against the despoliation of their pleasant urban landscape got bogged in “official channels”, then they would turn to the industrial clout of the communist-led BLF. Since the core political value of Mundey’s socialism was democratic decision-making (in the union, in politics, in society), the BLF required demonstrated resident support and majority rank-and-file BLF endorsement of any green bans. From 1970 to 1975, dozens of publicly-owned or community assets were saved by the BLF withdrawing union labour. The end came with the deregistration of the NSW BLF, the state Industrial Court agreeing with the black propaganda of the peak building employers' body, the Master Builders' Association (MBA), that the BLF had flouted the law and used intimidation on site. Whilst the MBA may have popped the victory champagne corks in their battle with the union, the longer-term environmental war was another matter. Mundey’s BLF had decisively shifted the strategic balance of forces. Fifty years ago, heritage and environmental preservation had no standing in law or government policy but there has since been a steady accretion of legal reforms, development assessment protocols and planning statutes. Mainstream politicians now find it obligatory, because there is “useful political mileage” (votes), in conservation to pay attention to environmental considerations which they once dismissed as extremist, back-door routes to socialism. Mundey, himself, was elevated from communist villain to the chair of the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, a government body. The “Green Tape” that has displaced the “Communist Menace” as the object of developers’ ire has its red roots but while Mundey explicitly saw a direct link between his environmental and socialist values, his chronicler, however, is more reticent. Colman, who might be best characterised as one of the “enlightened middle class” who constituted some of Mundey’s green ban clientele, believes that conservation is now respectable and politically “middle-ground”, and this requires him to dilute its more disreputable Marxist roots. Indeed, in Colman’s book, Mundey the Marxist is rarely sighted while the man himself is frequently submerged beneath the history of heritage architecture. Mundey’s textual semi-obscurity is partly his own fault (in self-effacing socialist style, Mundey requested that societal forces take precedence over the personal in his “biography”). But Mundey’s Marxist modesty is misplaced because, as Colman does briefly note, Mundey’s personal qualities and political beliefs ably fitted him for his pivotal historic role. In the face of reinvigorated threats to the urban environment from the weakening of environmental laws, cuts to funding, and legislative strong-arming of uppity unions, Mundey’s red-green palette still offers much to study and to apply.