Latin America’s new Right, “campism” and the need to de-hipsterise the Left: An interview with Pablo Stefanoni

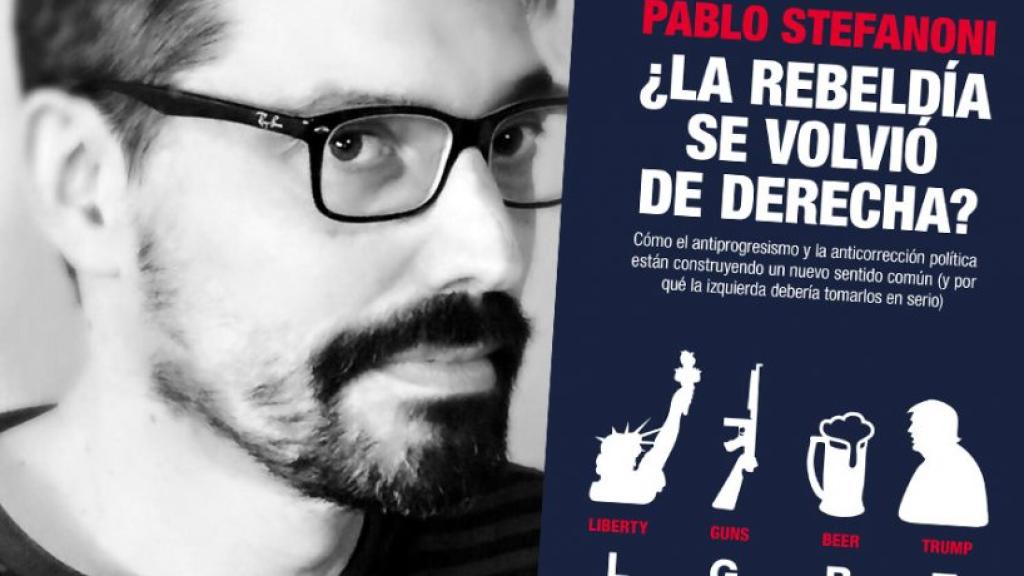

Pablo Stefanoni is editor of the progressive Latin American magazine Nueva Sociedad, associate researcher at Fundación Carolina (Spain) and author of La rebeldía se volvió de derechas? (Has Rebellion Become a Thing of the Right?). He spoke with Federico Fuentes, from LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, about the situation in South America after the Brazilian elections, the challenges posed by the far-Right, the impact of the Ukraine war and prospects for the Left.

There are two readings the Left could make of the recent elections in Brazil. On one hand, we can point to the confirmation of a new wave – or new Pink Tide – of progressive governments, given Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s return to power comes on the back of progressive victories in Chile, Peru, Colombia, Honduras and Bolivia. On the other hand, we could point to the consolidation of the new Right – or better said, the new Rights, in light of the differences that exist among these forces – which has displaced the traditional Right and almost won power in several countries. What is your assessment of the result in Brazil, and how much emphasis do you give to either of these two visions when attempting to analyse the current political dynamic in the continent?

In essence, both readings are correct. In Brazil, we saw the triumph of a very broad electoral alliance behind Lula da Silva, which encompassed almost everyone from the socialist Left to the centre-Right, along with sectors of the economic, media and judicial elites that found themselves in conflict with Bolsonaro. This alliance was, in part, a result of the centre’s inability to come up with its own attractive electoral offer. Lula’s return involved a very impressive process of political resurrection, but his victory was a long way away from being the result of a clash between the people and the oligarchy or between Left and Right. In the end, what won out was a kind of democratic front, led by Lula, formed in opposition to the enormous deterioration of civic, social and institutional life caused by Bolsonarism and the lumpen and criminal Right he embodied had created. And while Lula was able to “resurrect” himself, the Workers’ Party (PT) continues to be relatively weak. There are dynamic sectors to its Left, such as the Freedom and Socialism Party (PSOL), but they are still a small party. With this victory, the largest countries in the region are now governed by progressive forces.

But it is also true that Bolsonaro demonstrated he is the expression of a substratum of the Right that has radicalised in recent years and whose broad reach transcends him. It is a movement that rejects recent advances made in gender and racial rights and holds denialists positions when it comes to climate change. Moreover, we saw a regionalised vote, with the Workers’ Party (PT) very dependent on the poorest sectors from the north-east. Behind Bolsonarism are concrete interests: agro-industry; paramilitaries and sections of the security forces; and conservative evangelists – what in Brazil is called the three Bs: Boi (Beef), Bala (Bullets) and Bíblia (Bible). Bolsonaro was the fourth B that united these sectors in the last election. We will see if he can maintain his leadership into the future - he was not even able to create a party during his years in power - or if other Rightists leaders will emerge to challenge him. But it is clear that these sectors have held onto a strong institutional presence in parliament and in the governorships.

There are various reasons given as to why the new Rights have achieved these results. The most common of these focus on the role of the media (traditional and alternative, such as social media), the circulation of fake news or the rising influence of Evangelical churches. How much weight do you give to these factors? What about the impact neoliberalism has had on society, having helped create a social subject open to the ideas and visions of the new Rights? How do you explain the electoral pull of the new Rights? And are the new Rights here to stay?

In Brazil’s case, many of the main media outlets supported Lula. There are videos circulating of journalists from important newspapers celebrating Bolsonaro’s defeat. At the same time, Bolsonarism has demonstrated its effectiveness as a generator of fake news on social media and through WhatsApp, which is very popular in Brazil. And much of this online dirty war has found fertile grounds, for example, among the growing numbers of evangelicals. Part of this online war said that Lula was going to close churches and even went as far as claiming he had signed a pact with the devil, something that the PT forced to come out and “deny”. Anti-corruption discourse also continues to play an important role when it comes to discrediting the PT.

But, beyond this, there are societal changes that we need to look at more closely: transformations in the religious world; truncated social mobility; sustained improvements in consumption that were not matched by improvements in public services or the expansion of common goods and the welfare state under PT governments. All this has generated frustrations among sections of the so-called “new middle classes” and has led to reactions from others against the plebian “invasion” of universities, airports and shopping centres. While the PT promoted redistribution without class struggle – give to the poor without taking from the rich – according to various studies a strong class-based reaction was registered against these symbolic transformations. Additionally, as the academic Roberto Andrés notes in his article, the Lula period saw a leap in the importance of agro-industry in the country. The deindustrialisation of the south-east was accompanied by the growth of primary commodities production and consolidation of a strong agricultural sector in the centre-west. It was in this region that Bolsonaro obtained his best results. The regionalisation of the vote was very important in this election – and to Bolsonaro’s resistance.

Finally, on a more regional scale, we should not forget that almost half of the Latin American population is employed in the informal sector. Within this economy there exists a popular capitalism, which is permeable to meritocratic and even anti-state discourses. In Latin America, many see themselves as small business owners operating within an economy of precarity. This means that the discourses of the new Rights – which mixes libertarianism and conservatism – has a larger base than the Left sometimes imagine (the support of libertarians for Javier Milei among sectors of the lower middle class and even among popular sectors in Argentina is a good example of this). This issue cannot be resolved by saying people voted against their own interests or have “false consciousness”. The Left in the region, and in Brazil in particular, has made consumption the basis of its politics, without at the same time strengthening public services and expanding common goods. It is no coincidence that the protests against [PT president] Dilma Rousseff in 2013 began around public transport and demanded “FIFA-quality public services”, in reference to the public funds spent on the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics held in Brazil.

While the establishment supported Bolsonaro four years ago to avoid a PT victory, this time around the majority of the establishment supported Lula. To this we can add the fact that the new progressive presidents have been elected on more moderate platforms compared to those of candidates elected in the first wave (for example, Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, Rafael Correa, etc). Even Lula himself is not the same Lula that was elected in 2002. What does this tell us about the state of the Left today? What did you mean to say in your book when you wrote that the Left will continue to win elections, but “they can do very little once they win”?

Something similar to what happened with [former US president Donald] Trump, occurred with Bolsonaro: in the end, Bolsonaro came to represent a kind of vulgar and violent Right that, among other things, destroyed Brazil’s international reputation and became an obstacle to the normal functioning of the system. There is a dimension to this more “alternative” Right that ends up being anti-system within the system, questioning the institutions and sections of the elites, and generating uncertainty from above. This is the only way to explain why those sectors that hated Lula have now “amnestied” him.

Turning to the second part of the questions, it is true that today the Left seems to have less – let’s say – ideological energy compared to the first Pink Tide of 2005-15. In any case, I believe it is important to reassess the supposed radicality of that period. It is true that important transformations took place in various countries, above all changes in terms of the country’s elites that facilitated the coming to power of traditionally excluded sectors – that was very important. At the same time, I believe that the moderate-radical divide should be relativised when analysing this period. The most “radical” country, Venezuela – which was the only one to define itself as socialist after the fall of the Berlin Wall in addition to the existing ones – ended up an a mix of inefficiency, corruption and authoritarianism, with the collapse of Venezuela’s public services, in particular the healthcare system, with the rise of a dollarised economy, with a high level of growing inequality and with an enormous migratory wave. In Bolivia’s case, although the Evo Morales government was very efficient in the economic sphere – combining the nationalisation of gas with macroeconomic prudence – the advances made with regard to the social state are much more modest. Even Morales himself recognised towards the end of his third term that the “process of change” still had a debt owing with regards to the healthcare system (which is central to the lives of popular sectors). In general, the more radical discourses of the first wave did not have the capacity to enshrine changes in new institutions; instead there were a lot of ad hoc state policies, such as the “missions” in Venezuela. At the same time, part of the “revolutionary” discourse of that wave translated into authoritarianism or anti-pluralists visions for doing politics. We should not forget that Evo Morales did not recognise the results of the 2016 referendum regarding his reelection, which handed over the banner of democracy to the Right that in the end succeeded in overthrowing him via anti-democratic means. Or that the Bolivian president gave the maximum condecoration of the state to Equatorial Guinea dictator Teodoro Obiang (who has been in power since 1979) and said that he wanted to learn from “brother Teodoro” how to win with 90% of the votes. Venezuela has turned to much graver forms of authoritarianism – which even the Communist Party of Venezuela today denounces – and Nicaragua has directly been transformed into a dictatorship.

Unlike the first cycle, today there is a sector of the Left that denounces these drifts, above all Gabriel Boric in Chile, but also Gustavo Petro in Colombia. These Lefts have also raised the banner of environmentalism, which was absent within Left populism. These transformations are not easy but it is necessary to begin to discuss them. In summary: I do believe there has been a weakening of the Left populist discourses of the first wave as an ideological horizon – above all those of a Bolivarian mould. And the horizon of change has been reduced. That said, the victory of the Left in Chile and Colombia, with all its problems, has redefined regional geopolitics. The Alliance of the Pacific no longer exists as a liberal-conservative space that poses as an alternative to the Left, and the extreme Rights have been halted in Brazil and Chile. It is true that “utopic” horizon of changes and refoundational discourses have become less present, but we should avoid counterposing these difficulties with a supposed golden age of the Left at the start of the 2000s.

When I referred to the “little” that the Left could do once it won elections, I was referring to the Left more globally – the deception in Greece, partly in Spain – with forces to the left of social democracy. There, I believe, there is still a pending discussion regarding how to rethink the political economy of social change beyond a discourse solely directed against the mega-rich; this Oxfam-style discourse is attractive, but in my opinion limits discussion. Argentine writer Mariana Heredia has written about this in a recent book.

You argue that the new Right has built itself on the basis of anti-progressivism or a kind of Anti-Progressivism United Front. It could also be said that sectors of the Left have sought to build themselves by mobilising around anti-fascism, labelling the entirety of the new Right as a fascist menace. Do you think this strategy has been successful to date? Or do you see weaknesses with it?

I see anti-progressivism (now anti-wokeism) as the glue that binds together a highly diverse extreme Right, but one that operates – not without tensions – on common grounds (Steven Forti’s book has explained the differences within the extreme Right in a pedagogical manner). The idea that we live under a woke dictatorship; that the elites come from the Left; that Cultural Marxism has captured hearts and minds; all these ideas circulate among Rightists movements and parties, and on social media, in the global North and South. The problem when it comes to talking about fascism is that it does not allow us to capture the differences between this new Right and classic fascism. Today there are no militias; these movements are not palingenetic (they do not seek a kind of rebirth); and they interact with democracy, albeit in a complex manner.

That said, democratic fronts have halted the extreme Right in many parts, for example in France and Brazil. The issue is that “all against fascism” seems to confirm the Rights’ criticism that the components of this “all” are part of the same bloc, and often sees the Left tail-ending neoliberal forces. Meanwhile, the extreme Rights have largely been able to de-demonise itself: in France, the extreme Right have broke through the republican barriers in parliaments, going from 8 to 89 deputies; Giorgia Meloni was elected Italian prime minister in alliance with the centre-Right; Vox has allied itself with the Popular Party in various parts of Spain; José Antonio Kast won the votes of vast sectors of the moderate Right in Chile. Then the question arises: where is this fascism that the Left speaks off? There is something paradoxical here: it is true that the normalisation of the extreme Right pushes the limits of the thinkable/desirable, and breaks tacit post-war agreements; yet, at the same time, it places the Right in a position of being at risk of becoming too “normal”, of becoming part of the system, of the elite, of the political “caste”. Some of the difficulties the Left faces when it comes to changing the world are the same ones that the radical Right faces. We are not in the 1930s, even if we find some familiar resemblance with some aspects of those years. For example, in Europe’s case, the European Union imposes many limits, for good and bad. Today, everyone has less power in the face of the “system” – if by system we mean the globalized capitalism that we currently live under. And everyone seems to disappoint those who hope for deep changes – not just the Left.

Marc Saint-Upéry, in an overview written back in April of the Left’s response to the war in Ukraine wrote that “as a mobilising ideology of the masses and unilateral compass for credible projects of national development, anti-US anti-imperialism is dead and buried in Latin America”. How do you view the position/s on the Left - and the new Rights - in Latin America towards the war? Do you think the situation is as Saint-Upéry describes when it comes to anti-imperialism? Or is it the case, as other authors argue, that the prevailing vision is one of non-alignment, in which the region refuses to be part of a NATO crusade against Russia?

Anti-US anti-imperialism undoubtedly has a rich tradition in the region, which for obvious reasons has resisted interference from the US that viewed Latin America – above all, Mexico and Central America – as its backyard. The problem is that anti-imperialism, as we know, can go in many directions. For example, the Argentine military dictatorship of Jorge Rafael Videla also denounced US interference, the OAS [Organization of American States] and CIDH [Inter-American Commission on Human Rights] and even sought relations with the USSR. The problem is not anti-imperialism, but using it to smuggle in anything under its banner. Rather than anti-imperialism, what we often have on the Left is “campism”: thinking of politics as two camps in which one has to take the side – in automatic pilot mode – of those opposed to the United States. This is a debased version of the old campism that divided the world into a capitalist and socialist camp. If the USSR projected, in its own way, the perspective of an alternative to capitalism – even if it was a degraded version of the old utopias – post-1989 campism only serves to justify support for outright tyrants such as Bashar al-Assad, Muammar Gaddafi or regimes such as the Iranian one. Even some Latin American leftist leaders have showered these “anti-imperialists” with praise. That is why Evo Morales could congratulate Vladimir Putin on his birthday with a tweet that is worth quoting in full: “Congratulations to the brother president of Russia, Vladimir Putin, on his birthday. The dignified, free and anti-imperialist peoples accompany your fight against the armed interventionism of the US and NATO. The world will find peace when the US stops killing people.” That Putin finances the European extreme Right; that he sees the war in Ukraine as a holy war against the Satanic West; all this has no importance for these referents of the Left who bought the discourse of “de-nazification” or the idea that this is all a product of “NATO expansionism”, without analysing Russia’s own imperialist dynamics or the fact that for many neighbours, joining NATO seems quite rational if Russia is going to operate as the big bully in the neighbourhood. This is a Left that says nothing about Nicaragua, where there are increasing numbers of dissidents in jail, including Leftists – which in this case is a bit absurd because Ortega developed good relations with the US Southern Command, the IMF and other “imperial” institutions.

On the other hand, as both Saint-Upéry and I have written about in separate articles, in the last instance, and when it comes to deciding how to vote in the United Nations and other institutions, the positions of the governments in the region have, in their majority, responded to the traditional normative vision of international relations that has characterised Latin American political culture and its vision of the world, and, in particular, the traditional foreign policy pursued by foreign ministries and diplomacy. In sum, Latin American foreign policy is rooted, above all, in the principles of respect for equal sovereignty of states and non-intervention.

And it was not only the left that was ambivalent about this issue. As an article in BBC in Portuguese noted: “the most radicalised wing of the Brazilian Right is divided on this conflict, as one part flirts with the Ukrainian Right, while another admires Putin”. On travelling to Moscow, Bolsonaro declared that “Putin is conservative, someone like us”. In fact, the second ideological stop on his tour was to visit Viktor Orban, where he said that “the governments of Brazil and Hungary share ideas that can be summed up in four words: God, homeland, family and freedom”.

Lastly, the radical Left in general tends to say that the response to the new Right will have to come from the streets and the social movements. Do you think that in the current situation this is enough? What is the Left lacking today? Or, to put it differently, what is the biggest challenge that the Left which wants genuine change faces?

In my opinion, the challenge is to reformulate the reform-revolution duo. With revolution not on the immediate horizon – for good or bad, given the results we have seen so far – it is necessary to breathe new life into social reforms, which the reformists have abandoned. There are a series of enormous issues to deal with: climate change; new forms of alienation (how to grapple with new technologies?) and precarity; the need to, in some way, rebuild welfare states (in Madrid, half a million people mobilised a few days ago for healthcare – arranging a consultation with a specialist can take months, and even up to a year). It is unlikely that this can be done using the parameters of hyper-political correctness or by attempting to consolidate niche identities. Instead, it will require combining emancipatory perspectives – on issues such as feminism and sexual diversity – with a capacity to win over even broader popular sectors – with all their diverse and contradictory sensibilities – on a multiplicity of societal problems. In a precarious world in which the future seems bleak, it is not enough to deconstruct everything. We need to construct images of what a better life could look like.

I believe we need a certain de-hipsterisation of Leftism, to reconnect with those below, and once again take up “hard” economic questions: today, talk of post-capitalism almost never takes up the economy, outside specialist circles. Catastrophism can be pedagogical, but it can not help us refound emancipatory projects. I don't know how to do all this, but it will depend on concrete experiences that allow for certain universalisation, forms of rebuilding community, and creation of spaces for discussion and decision-making. Ecosocialism, in this context, could provide some imageries for reconstructing positive and desirable images of the future.

Despite having written a book that seems quite pessimistic, I do not believe the Right is winning on all fronts. In fact, I believe its radicalisation is often due to the fact it is losing. But what it has achieved is an increasingly unequal capitalism that comes with a “progressive” discourse regarding gender, race, sexual minorities. That is why there is such great confusion. The problem, in any case, is that parts of the Left have focused on discourses that in large part abandon a more universalist/class-based perspective. While talking all the time about intersectionality, the class dimension of this equation of unequalness is the least discussed. Without recuperating some kind of class identity – which will not be the same as those of the past, nor can the issue be resolved by adopting conservative or anti-woke positions – it will not be easy to wage the battles that await us.