Austria’s European Union election results: A step forward for the left in troubled times (plus Communist Party of Austria: Setting ourselves apart)

First published at Transform! Europe.

In Austria’s recent European elections, the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) accomplished a remarkable surge, quadrupling its vote share. Although it hasn’t won any seat, its historic performance signals a potential revival of the left. As national elections approach, the KPÖ’s growing support, especially among young voters, offers a glimmer of hope for future parliamentary success.

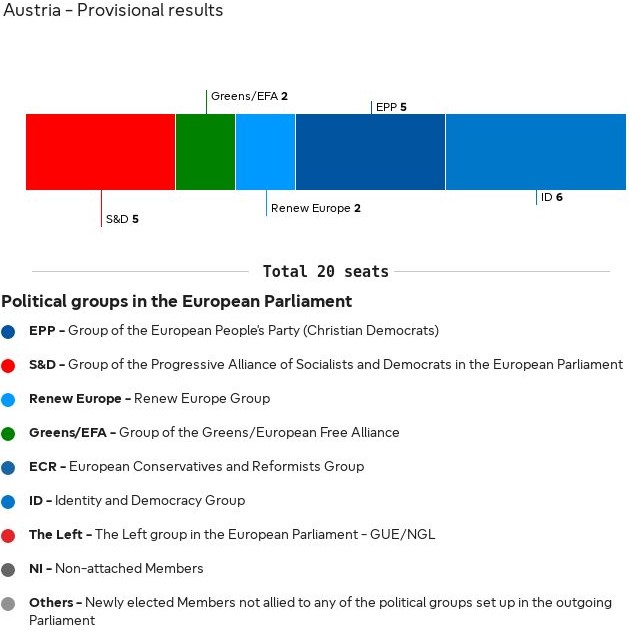

In the European elections held on 9 June, 20 seats in the European Parliament (EP) were elected in Austria for the first time (since Brexit released the UK’s seats, which have been distributed among the remaining member states). The election – with 56.3% turnout, roughly the same as in previous EU elections – was unsurprising in terms of the parties’ rankings: in addition to the election victory of the extreme right, the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) quadrupled its previous vote share, even though this was not enough to secure a seat in the European Parliament.

The right-wing extremist FPÖ emerged as the strongest party after the election. However, with 25.4% (plus 8.2%) and 6 mandates, it fell short of the forecasts, which had predicted up to 32% for the FPÖ, which is situated on the extreme right of the ID group of parties in the EP. It was followed by the conservative ÖVP, which belongs to the EPP, and suffered a major loss of 10% but still finished in second place with 24.5% and 5 seats. The Social Democratic Party (SPÖ, S&D), whose new leader had previously described himself as a “Marxist” but enjoys little support within the party, stabilised at 23.2% (down 0.7%) and will continue to send 5 representatives to the European Parliament. The Green Party’s election campaign was overshadowed by a scandal surrounding the credibility of its lead candidate, which dominated the headlines for weeks. Nevertheless, the party’s losses, which ultimately reached 11.1% and secured 2 mandates, were unexpectedly small at 3%. The SPÖ and the KPÖ profited from this but so did the neoliberal NEOS (Renew) party, which called for a “United States of Europe”, achieving 10.1% (up 1.7%) resulting in 2 mandates.

A strong sign of revival for the left

The KPÖ (EP group: The Left) achieved a historic result of 3% (up 2.2%) and almost 105,000 votes, which is four times as many as in the last European elections. It focused particularly on the issues of neutrality, peace, inflation, housing, and lobbying. The last time the party achieved a comparable result in a nationwide election was in 1962. In this election, the KPÖ was able to attract new voters everywhere, but the result in the capital Vienna is particularly noteworthy, where 4.7% (up 3.4%) would have been enough to cross the electoral threshold and enter the European Parliament. The election results in the party’s two regional strongholds, Graz (6.8 %; up 4.8%) and Salzburg (6.2%; up 4.8%), as well as in the other provincial capitals of Linz (4.7%; up 3.4%) and Innsbruck (4.4%; up 3.5%), contributed significantly to the nationwide growth. The fact that the sensational election results in the regional elections in Graz (28.8%) and Salzburg (23.1%) did not translate to the European level shows that the KPÖ still has work to do regarding supraregional elections. In any case, it seems encouraging for the future that the KPÖ received 10% of the under-30s, a similar level of support to that of the Greens (12%).

Voter mobility

The voter flow analysis also shows the extent to which the KPÖ has been able to reach voters who were previously largely inaccessible: the party was able to attract 32,000 voters who opted for the Greens in the last EU elections, followed by 18,000 voters from the conservative ÖVP and 15,000 previous non-voters. It is also worth noting that 10,000 former voters of the extreme right were won over, while only 7,000 votes came from former SPÖ voters. This shows that the KPÖ’s strategy of convincing non-voters and FPÖ voters who are particularly socially disadvantaged has been partially successful. The KPÖ’s growth is therefore only to a small extent at the expense of the centre-left parties, which is encouraging with regard to the parliamentary elections, which will now take place on 29 September 2024, and it also calls into question the anti-communist propaganda of the established parties. This insight could potentially bring about a change in the media landscape, where the KPÖ has been given only a fraction of the coverage given to the other parties. The KPÖ was not invited to any of the many nationwide TV debates on state or private television, and it also had less presence in the left-liberal press than in the tabloids and conservative media.

Themed failure in the media during the election campaign

The choice of topics in the media and among the parties is also likely to have had an influence on the result: while the social upheaval caused by the inflation crisis was still the focus of media attention a few weeks ago, towards the end of the election campaign the topic of migration, for which the parties hardly have any constructive and rational answers, was increasingly pushed to the fore. While the population continues to struggle with rent increases of around 30% in recent years, the ÖVP and FPÖ in particular engaged in a racist duel. Towards the end of the election campaign, the conservative chancellor received his British counterpart in Vienna and then called for the implementation of the “Rwanda model”, which violates the European Convention on Human Rights, for the first time. The SPÖ, which supposedly has a left-wing leadership, also took the opportunity to call for the illegal deportation of refugees to Afghanistan and Syria. During this obfuscatory debate, it happened that large parts of southeastern Austria were submerged by floods, while Austria’s government is currently blocking the European Nature Restoration Law, aimed at restoring the natural river courses. The same can be said of the issue of war and peace, with the public debate fed by a logic of war, as is the case throughout Europe – despite Austria’s neutrality. For example, there was extensive discussion about arms deliveries to Ukraine, while Austria’s constitution actually prohibits such steps altogether. While the FPÖ – in line with its friendship treaty with the United Russia party – put up posters of the President of the European Commission kissing the Ukrainian President, it was left to the KPÖ to call for the revival of diplomacy for a ceasefire and the right of asylum for Russian and Ukrainian deserters. The other parliamentary parties have focused exclusively on military support for Ukraine in various shades, denouncing peace policy approaches as taking sides in the conflict. This hegemony of the logic of war also made it difficult for the KPÖ to convey its honest commitment to peace.

Parliamentary elections in autumn

This year, the political players in Austria will only be allowed a short summer break. As the national elections are scheduled for 29 September, the parliamentary parties will probably start their election campaigns in mid-August, but the KPÖ as an extra-parliamentary force, which had to collect 2,600 signatures to be on the ballot paper in the EP elections, will have to collect another 2,600 signatures from voters (which have to be done in person in front of the local authorities) by the beginning of July to be on the ballot paper in the national elections. The media have already declared the election campaign to be a three-way fight between the FPÖ, SPÖ and ÖVP, with the extreme right having declared for months that they want to make their leader the “Volkskanzler”, which is a direct reference to the National Socialist period. Consequently, all other parties are now distancing themselves from any participation in a government by the FPÖ. However, it is questionable whether this distancing will be maintained, especially in the case of the ÖVP, if its political leadership is replaced as a result of an expected election loss. There are also voices within the SPÖ suggesting that the party should cooperate with the neo-fascists in the future, although they are currently in the minority.

Looking at the KPÖ, the conditions that could allow it to become a parliamentary party seem more favourable than they have been for a long time. As early as autumn 2023, a party conference decided that the federal spokesperson Tobias Schweiger, a former official of the Green Youth from Styria, and Bettina Prohaska, a care worker from Salzburg, would form a dual leadership for the elections. With a different thematic focus in the media, the now united KPÖ, which focuses on social issues, health, and human rights, could succeed in taking the necessary second step. “We see our task as building trust with people who do not have a lot of money to make ends meet”, emphasised Schweiger after the election, pointing out that the party had only 50,000 euros available for the election campaign and was not invited to any TV debates. The KPÖ will continue its social counselling and support services after the elections. “It’s about having a concrete practical value for people, not dazzling election promises”, said Schweiger. In order to enter parliament in the autumn, the KPÖ must mobilise not that many more votes than it received this June and faintly reflect something of the high numbers it has received locally in Graz and Salzburg. Since the party only needs to win more than 4% of the votes nationwide or a direct mandate by winning a particularly large number of votes in a constituency, the chances of its re-entering parliament, 65 years after its departure, seem better than ever.

Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ): Setting ourselves apart

Georg Kurz & Sarah Pansy. First published at Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

If you ask a random passer-by on the streets of Salzburg what sets the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) apart, they will probably have quite a bit to say — regardless of whether they vote for the KPÖ or not.

For example, it is well-known that KPÖ representatives give away a large portion of their salaries to avoid becoming out of touch with the people, and that this money is shared with those who need it more urgently, all without any bureaucratic red tape. The average passer-by is also likely to know that the party campaigns tirelessly for affordable housing. All in all, there is a good chance that our random interviewee will conclude that the KPÖ does not take part in squabbling with other parties; they are there “for the people”.

For a party that had previously only held one of the 40 seats in the municipal parliament and was therefore inconsequential in the balance of power in Salzburg’s city government, this is quite an achievement. The KPÖ is adept at raising the concerns of the population in the local council and the media more visibly than the other parties, but it is outside of parliament that the party’s efficacy is most unmistakable. And that is precisely what sets its understanding of politics apart from that of all other parties: yes, we KPÖ members run for elections, use our speaking time in parliament, and submit motions there. But we do so knowing full well that the majorities needed for transformative policies are not organized in parliament.

If you don’t have a majority, create one

A great example of this can be found in Graz: in the 1990s, KPÖ council member Ernest Kaltenegger put forward a motion that no one should pay more than one third of their income on rent for the city-owned apartments, which had become increasingly expensive. At a time when neoliberalism and privatization were at their peak, he was of course alone: the motion was rejected by all other parties.

Had he done so as a member of any other party, this would have been the end of the story: “Too bad they didn’t want it, we had such good arguments, but unfortunately we don’t have a majority.” However, the Graz KPÖ took action, launched a major campaign and worked together with tenants to collect 17,000 signatures. The public pressure was immense, leaving the other parties no choice: the KPÖ submitted the motion again, and this time it passed unanimously. The KPÖ had effectively created its own majority in parliament.

This was confirmed at the next election in 1998: with just under 8 percent, the party almost doubled its popularity, laying the groundwork for further successful campaigns and achievements which culminated in 2021. With 28.8 percent, the KPÖ is now the strongest force in Graz. Party member Elke Kahr currently serves as mayor in the city, and she has only become more popular since taking office.

The example of the Graz comrades clearly demonstrates why the KPÖ does not completely forgo a strategic use of parliament, but our power is firmly rooted in the work we do in neighbourhoods, not in parliament.

You can’t make a career in the KPÖ

We wouldn’t be the first to start out with such lofty ideals, but there is of course the risk that sooner or later, we would fall for parliamentarianism just like everyone else: after all, parliaments are set up precisely so that their members are systematically kept away from the rest of the population and their everyday problems, ensconced in luxurious buildings with every conceivable amenity, hefty salaries, chauffeur services, staff, and the like.

For this reason, the KPÖ has followed the example of the Paris Commune in creating fixed structures to avoid the parallel world of professional politics: anyone who accepts a mandate for the party, whether as a local councillor or a senior member of government, receives at most the average skilled worker’s salary, which currently stands at 2,500 euro. Anything that exceeds this amount is returned directly to the population during consultation hours, without any bureaucracy.

In Salzburg, we were able to provide concrete help in hundreds of cases last year. That is a value in its own right. Even the KPÖ politicians who perform the social consultations as part of their everyday work for the party benefit from them: Any politician who has to confront issues such as mould in social housing, rising gas bills, and a lack of access to German language courses, rather than deal with committee agendas and lobby meetings will eventually change their political perspective. The salary deduction is a substantial proof that we keep our promises: we can implement this even the day after the election. It is apparent to everyone that we not only talk, but actually take action.

However, the consultation hours are not the only way we avoid getting too wrapped up in the machinery of government: KPÖ representatives also perform organizational functions in the party, take part in other tasks that emerge, and are constantly in contact with everyday people, not only through consultation hours but also through other party activities such as information stands, collecting signatures, and door-to-door canvassing.

Working in parliament or government is a necessary service to the party, just as cleaning its office and distributing its newspaper are necessary tasks for the party’s success. However, no position exempts the officeholder from their other duties: we in the KPÖ are dedicated to organizing social life. This primarily takes place outside of parliaments, which is why our work is not focused on parliamentary politics.

The majority Is there, you just have to organize It

As the example from Graz demonstrates, our effectiveness stems largely from the fact that we can legitimately say loud and clear that our work reflects the concerns of the majority.

We constantly receive positive feedback on our practical work in Salzburg. People appreciate it because they see the benefits. This lends us a legitimacy that extends far beyond our voter base.

That is why, in everything we do, we focus not on what is divisive, on the disagreements between different interest groups, but on the common interests of the 99 percent. We prioritize the particular interests of minorities not only because we think it’s the most effective way to concretely improve the lives of those concerned: sound social policy is often the best way not only to help disadvantaged people, and it also garners the support of the majority.

Ultimately, improving the real situation of people in neglected neighbourhoods benefits marginalized and disenfranchized minorities most. The same is true for our consultation hours and other support services. We are not interested in divisive cultural battles, identity politics, or symbolic gestures — rather, we are fully committed to the material improvement of collective living conditions.

Who are our people?

An effective left-wing party is a party not just for the Left, but for all wage earners. Our target audience is not the left-wing scene, but everyone who is dissatisfied with the prevailing conditions and the established parties: the disaffected, the marginalized, the disillusioned, the non-voters.

Up until now, their main option in terms of political representation has been the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ). However, the motivation for voting is often not based on any adherence to moral worldviews, but rather the feeling of being taken seriously, and the identification with the marginalized. This can be achieved by positioning ourselves outside the consensus of the other parties. In this way, we build up a base of supporters who will remain loyal to the KPÖ in the long term and instead of remaining undecided in the lead-up to elections.

The KPÖ steers clear of the other progressive parties’ turf: it does not aim to redistribute votes within the left-wing camp, nor does it aspire to be a superior version of the Greens, or a more left-leaning Social Democratic Party (SPÖ). These parties’ potential is limited anyway. If we aspire to build majorities, we need to cast a wider net: we go almost exclusively to the neighbourhoods and to the people which have long been forgotten by the established parties, where people either do not vote at all or vote for the right. This explains why we do not even attempt to compete with the other parties and deliberately avoid the usual political squabbles, demands for resignations, and mutual accusations — the KPÖ is concerned with the half of the city that has stopped participating in elections.

By gradually bringing them back into the fold of urban society and integrating them into our work, we exert a lasting influence on the political landscape. The KPÖ is engaged in democratizing areas of society that have turned their backs on established politics for good reasons. The party’s growing support in these areas is a cornerstone of the type of systemic change we strive for.

Pressuring the state and organizing society

Public interest in the KPÖ rises dramatically after every successful election. However, our focus has long extended beyond electoral results — for us, they are more of a litmus test of how far our year-round work has borne fruit. We have a broader understanding of our potential as a party: we want a society based in solidarity, so we have already begun organizing it. We do not rely on the state to sort matters out for us — we are “deinstitutionalizing” by building community structures ourselves and gradually taking on more and more state responsibilities.

Seemingly apolitical activities such as flea markets, street festivals, tenants’ meetings, tutoring sessions, waste collection, neighbourhood kitchens, book clubs, repair cafés, and German courses all have a clear goal: to bring people out of their isolation and enable them to experience community and shared interests. This is a necessary prerequisite for being able to survive amidst major conflicts. We’re not exactly living in revolutionary times — so the question is, how do we bring about real change?

Without class consciousness, there is no class struggle. And without confidence in the Communist Party to represent these class interests, these struggles cannot succeed. People who have not even experienced the possibility of improving their own living conditions will have little faith in the prospects for a liberated society. As long as our own neighbourhoods are not organized, there is no point in talking about world revolution.

When we look back on the major Communist movements of previous centuries, we tend to remember mass demonstrations and general strikes. However, we often forget that a prerequisite to all of this was the years of arduous groundwork in the pre-political sphere.

Why we call ourselves Communists

“It’s always the same with politicians, no matter which party” — such statements are based on real experiences of the past decades and are therefore difficult to overcome. That is, unless you call yourself a Communist Party and consciously position yourself outside the established political system.

People believe that we really want to make a difference. This is appealing to non-voters and protest voters. The more the established parties join forces and rally against us, the more they involuntarily play into our central message of being “different from the others”.

The fear-mongering of the other parties has largely been ineffective because the KPÖ consciously defies all the stereotypes associated with evil Communists: we present ourselves as remarkably approachable, constructive, and warm, we are always smiling, and our posters consist exclusively of friendly people and positive messaging.

Beyond all strategic considerations, it is more urgent than ever to put a concrete alternative to the world’s misery back onto the agenda. The communist idea has empowered masses of workers to fight for all the improvements and rights that we take for granted today. We stand on their shoulders. Learning about the forgotten political tradition we are part of transforms our perspective on history and the world.

Building credibility

A political party is an abstract construct and it takes a long time for people to really trust it. An individual who embodies our values for all to see exponentially improves our recognizability and is much quicker to receive the endorsements we are working towards.

The recognition and public image achieved by individuals like Kay-Michael Dankl in Salzburg or Elke Kahr in Graz have been cultivated fastidiously. This requires years of consistency. The ultimate goal, of course, is to have people to trust the KPÖ as an organization as a whole. We have already made significant progress in this regard. Nonetheless, putting certain individuals in the spotlight is a necessary starting point for this process.

Why do we focus on housing? Because two crucial factors converge in this single issue: on the one hand, the housing crisis is severe, and on the other, there is a broad public awareness of this issue and a willingness to address it with policies driven by concrete needs rather than profits: There is majority support for the notion that the market should not be left to determine housing.

On paper, all parties are in favour of affordable housing. But if people do not believe that a particular party will actually make a difference after the election, then their position is irrelevant — there is no reason to vote for them.

Making a real difference with respect to an issue which has been considered a lost cause for decades requires an uncompromising pooling of forces. Simply demanding improvements is a tempting but ineffective approach. Actually enforcing their implementation is laborious and requires tons resources. The example from Graz illustrates that years of strenuous effort are required to achieve even a minor victory. It is impossible to accomplish this if you are fighting for all the other important left-wing issues at the same time.

For this reason, if we truly wish to make a difference, we must overcome the moral reflex of wanting to advocate every good cause in the world while simultaneously opposing every bad one. Otherwise, we will end up with a clean conscience, but the real conditions would still be determined by others. We have made a conscious decision to do what successful parties do instead: focus all our energy on a central issue of our own choosing.

The decline of the FPÖ

Despite leading in all national polls for a while and appearing untouchable, the FPÖ has failed to make headway in Salzburg. On the contrary, as was previously the case in Graz and now also in Innsbruck, the party has fallen far short of expectations, largely due to the fact that we are not doing the FPÖ the favour of antagonizing them.

We do not talk about their favourite topic: immigration. We talk about housing and work constantly on housing, campaigning non-stop on the issue, thereby forcing the other parties to address the issue, and shutting down the FPÖ’s “kick out the foreigners” rhetoric in turn.

Shortly before the election, the right-wing parties in Salzburg also took up what had long been established as the central election issue: housing. The FPÖ’s final mobilization consisted of life-size cardboard cut-outs of the lead candidate holding a sign. Contrary to expectations, it did not read “For more deportations” or something like that. Instead, it said: “I stand for affordable rents.”

Previously, the FPÖ (similar to the conservative ÖVP) had warned of the “leftward lurch” with large posters adorned with a hammer and sickle. This was clearly a reference to us and our core issue — the other parties define themselves in relation to us. By doing so, they only confirm our own argument: everyone is against the KPÖ, we are the alternative.

This is something we must be able to live with, and it is okay if there is always someone issuing shrill warnings against us, while at the same time gradually adopting our positions. Similarly, many have been warning against the FPÖ for decades, but this has never hampered their rise. Instead of warning against their agenda, we are now playing on our own turf.

We’re just getting started

The KPÖ is giving people a sense that there is a real alternative to the established parties, someone in politics who is listening to their concerns. People know they can go to the Communists with their problems and that they will be taken seriously. We are a party that delivers what we promise before the election.

This process of building trust is already bearing tangible fruit, and our success in the municipal elections has made this visible to the outside world. The fact that the KPÖ is now part of the city government does not change the fact that we will continue to focus on what makes us strong, that we may continue to build our strength. We’re just getting started.

Georg Kurz is a coordinator of the KPÖ election campaign in Salzburg. Sarah Pansy is a member of the Salzburg state parliament for the Communist Party of Austria. Translated by Diego Otero and Hunter Bolin for Gegensatz Translation Collective.