Australia: Fighting AUKUS in Wollongong

In March 2023 former prime minister Scott Morrison identified Port Kembla, Newcastle and Brisbane as three sites short-listed for a future east coast base for Australia’s promised AUKUS nuclear-powered submarines.

Located in the City of Wollongong, Port Kembla is a major industrial centre south of Sydney, and the third largest industrial port in Australia’s largest state. It has long been a hotbed of social movement and industrial militancy. It was in Port Kembla that wharfies famously refused to load the tramp steamer Dalfram in 1938, when they learned that its cargo of pig iron was bound for Japan, and its occupation of China. Australian pig iron, the wharfies saw, was being used in the massacre of Nanking and would soon be raining down on Australia as “bombs and bullets”. The dispute escalated nationally and earned then attorney-general (and future prime minister) Robert Menzies the enduring nickname “Pig Iron Bob”.

There has been significant social, cultural and economic change in Wollongong in the nearly 90 years since the pig iron dispute. Today, a worker in Wollongong is more likely to work in health care and social assistance (17.3%) or education and training (11.2%), than in manufacturing (5.7%) or on the waterfront (transport, postal and warehousing, 4.5%). But the example set by Port Kembla waterside workers remains a living tradition.

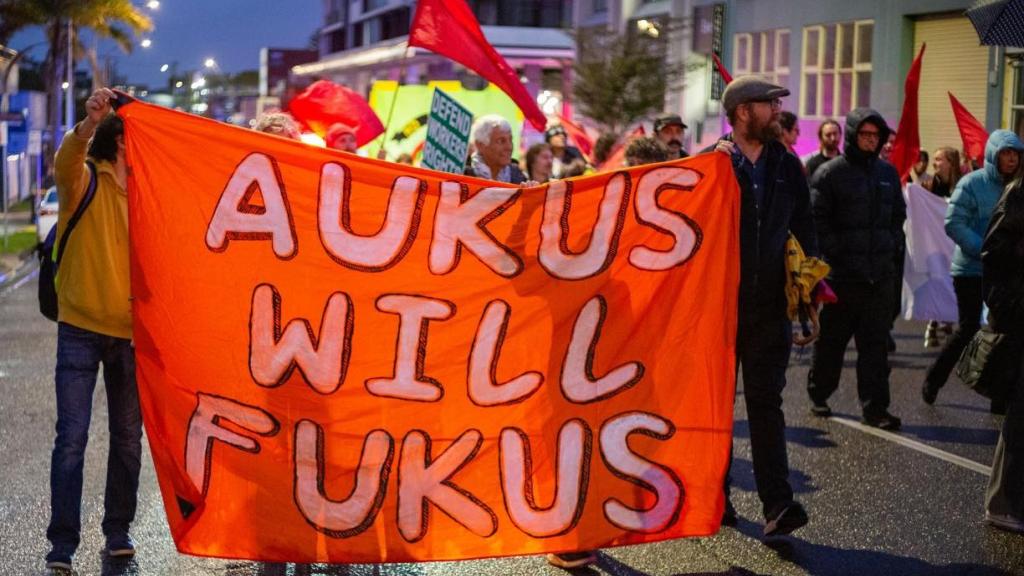

Shortly after Morrison short-listed Port Kembla, Socialist Alternative activists at the University of Wollongong called a rally against the submarines in the city mall. It was attended by a cross-section of the community and addressed by students, local Greens city councillors, union leaders and community members. After the rally, Wollongong Against War and Nukes (WAWAN) formed and began organising an ongoing campaign to stop the submarines. Support was broad-based, coming from Greens and Labor members (including some councillors), left union officials and others.

The campaign escalated in 2023 following leaks to the media suggesting Port Kembla had firmed as the preferred location for an east coast base. The first WAWAN protest of the year was held outside the Defence Industry Conference, organised by local business peak body Business Illawarra to drum up arms-related business for local engineering and manufacturing concerns. The rally clarified the relationship between the nuclear base and the broader project of military industrialisation in Wollongong, both of which have the support of the Labor Party leadership. However, while visiting Wollongong for the defence industry conference, Labor Assistant Defence Minister Matt Thistlethwaite announced that any decision on an east coast submarine base would be delayed until at least the end of the decade.

The Defence Industry Conference was followed by the historic 2023 May Day March for Peace, Jobs and Justice at Port Kembla, when thousands of community members, unionists, socialists and peace activists from Wollongong, Sydney, Canberra and further afield marched in opposition to the base. WAWAN’ analysis was that Labor, having received a clear message from its union affiliates and local branch members that siting a base in Port Kembla would be contested, chose the path of least resistance by delaying a painful decision that would affect it in key seats in the Illawarra, while retaining its broader commitment to AUKUS. Having won a temporary reprieve, WAWAN shifted its focus to building long-term resistance to the militarisation of the city.

The huge escalation of Israel’s genocidal war against the Palestinians in October 2023 shifted the focus of anti-war organising in Wollongong. Solidarity with Palestinians brought different social layers into the anti-war movement, including more young people, students and members of local migrant communities with kinship and cultural ties to Palestine and the Middle East. Wollongong Friends of Palestine was established to coordinate solidarity action. Weekly marches held by the group in central Wollongong were well attended and although numbers have dropped off somewhat as the war drags on, continue on a fortnightly basis.

For WAWAN, organising against Israel’s genocide while maintaining local opposition to the subs meant rethinking and repositioning its work. In March 2024, when a second regional Defence Industry Conference was held in Shellharbour, WAWAN cooperated with Wollongong Friends of Palestine to protest the event. WAWAN highlighted the relationship between the desires of local business leaders and politicians to convert Wollongong’s industrial base for military industrial purposes and the war on Gaza by demanding an end to arms exports from the Illawarra to the Israeli Defence Force.

This demand emerged from a campaign of direct action initiated by local people who discovered that local steel manufacturer Bisalloy was producing armour steel for Israeli military contractor Elbit Systems. The company is also contracted to provide hull steel for the AUKUS submarine project. The campaign began when small groups of individuals occupied the facility and locked-on to equipment in late 2023 and early 2024. Since May 2024, there has been a series of rolling community pickets of Bisalloy’s Unanderra factory, the sixth of which took place in May this year. The first picket also coincided with the establishment of a long-running series of encampments and protests at the University of Wollongong. Remarkably, the pickets at Bisalloy have yet to suffer a single arrest and have successfully disrupted operations at the factory, with the company directing workers to stay home for the day shift on at least three occasions.

War as industrial policy

The Bisalloy blockades have been particularly important not only because of their militancy but because they contest the industrial policy that lies at the heart of the AUKUS pact. Speaking at the Lowy Institute a few days after Morrison first announced AUKUS in March 2022, then Opposition leader Anthony Albanese not only pledged Labor’s support for the deal but outlined three pillars of Labor’s national security policy: territorial defence, sovereignty, and “promoting Australia’s economic and social stability, with sustainable growth, secure employment, and a unified community.” Albanese linked AUKUS to Labor’s Future Made in Australia Plan, promising to insulate Australia from an increasingly chaotic world by developing a sovereign manufacturing capability. In the 2024 federal budget, Labor’s support for Australian manufacturing was dominated by defence-related spending, including AUKUS submarines and other heavy infrastructure.

Back of the envelope calculations show that the AUKUS plan will cost $18 million per job created. But in a climate of global instability, the appeal of militarist nationalism has seen even the Greens jump on the national security bandwagon, with Greens NSW Senator David Shoebridge jettisoning the party’s longstanding opposition to militarism in favour of developing a “sovereign capacity” to manufacture deadly missiles and drones. Of course, this turn to a populist “independent” and “sovereign” defence policy is not only an affront to internationalism and a distraction from necessary cross-border cooperation on climate change, it is absurd in a world where defence manufacturing projects involve globally integrated supply chains.

In Wollongong, the prospect of war as industrial policy has profound implications for the future of its industrial base. Back in 2009, the South Coast Labour Council (SCLC) commissioned a report that led to the formation of the Green Jobs Illawarra strategy. This green new deal policy suggested a positive way forward for the region, with the potential to preserve manufacturing jobs while building on the region’s strengths in research and innovation to address the threat of climate change. By contrast, the submarine base and associated defence industries exploit growing geopolitical tensions, fanned by Australia’s China threat industry, with its ties to US arms dealers.

Liberal Party figures in Wollongong, including NSW Right figure Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, have pushed the idea of Port Kembla becoming a naval facility since well before the AUKUS announcement. In 2015 the Illawarra office of Regional Development Australia released a report extolling the virtues of relocating Australia’s Fleet Base East from Garden Island in Sydney to Port Kembla. The same coalition of local interests have lent their support to the submarine base proposal. Many local business interests, such as those associated with steel manufacturing, have hedged their bets, lending support to both initiatives.

The two possible futures for Wollongong became starkly visible in 2023, when a significant element of the Green Jobs strategy was set to come to fruition. The federal government held a public consultation on a proposed offshore wind zone for the Illawarra. The proposal enjoyed strong support from Green Jobs Illawarra partners. However, a Trump-style anti-wind farm campaign appeared as if from nowhere, organised by a core of activists (including some with connections to the anti-lockdown and COVID denial movement) and National and Liberal Party figures.

The campaign spread spurious claims about environmental harms, including a fake article claiming to be from a peer-reviewed journal linking offshore wind to whale deaths. It attracted many residents, some with genuine concerns about the impacts offshore wind might have on ocean ecosystems, and others concerned about their million-dollar views. In October 2023, opponents held a large rally against the proposal with speakers including candidates from the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, as well as local surfers.

The Good for the Gong campaign, led by local environmentalists, including some with ties to the Greens and Labor, has sought to defend offshore wind. Unfortunately, despite weathering the storms of neoliberalism better than most parts of Australia, the trade union movement in Wollongong has never recovered from the devastation of the Accord period, when union officials agreed to police industrial militancy on behalf of Labor and the employers, leading to a huge decline in workplace democracy and grassroots union membership.

In the context of vastly weaker unions, Green Jobs remains largely the preserve of the union leadership and class-conscious union members within older, established sectors of the working class, together with the technically trained professional, scientific and engineering workforce, which has grown in size and significance since the 1990s (including in and around the University of Wollongong). Wollongong’s population has also grown, with significant in-migration from Sydney. These more recent arrivals lack ties to the established working-class institutions that still dominate local governance.

Good for the Gong has organised primarily online and lacks open democratic structures that could enable grassroots participation. Its proximity to Wollongong’s Labor and Green establishment has not generated the populist passions of the anti-wind movement. At the same time, the anti-wind movement has not proved to be enduring. Its ragtag organisation has little grounding in local institutions and lacks deep roots in the proletariat. Like Good for the Gong, it is a largely online phenomenon, but without local institutional support has been kept alive by shady figures with ties to conservative political parties with few members in Wollongong.

The consultation process eventually culminated in the declaration of an offshore wind area, but the only commercial proponent still interested in building the infrastructure, BlueFloat Energy, asked that its application for a feasibility license be suspended in February following then Opposition leader Peter Dutton’s threats to cancel offshore wind projects if elected. The episode has been an object lesson in the instability of institutions in the current period, where populist insurgency can threaten long-made plans but lacks the organisational ability to propose concrete alternatives.

Whither Wollongong?

With Trump’s on-again, off-again tariffs threatening Port Kembla steel and the potential of a renewables manufacturing hub neutered (at least temporarily), there is a high risk that participation in a US-dominated arms industry will be presented as the only choice for sustaining Port Kembla’s manufacturing future. The wedge politics around nuclear that Dutton pursued during the federal election campaign amounted to little more than a culture war at the national scale. Nevertheless, together with Labor’s ongoing commitment to militarism, opposition to renewables may serve to derail alternative paths of economic development long enough to allow military industrialisation to gather speed.

Reflecting on the pig iron dispute of 1938 is instructive here. The power of the working class to resist Australian and Japanese militarism emerged out of a bitter struggle against unemployment and the ruthless exploitation of workers in the coal mines, on the waterfront, and in the steelworks. Working class activists were prepared to defy industrial laws, and risked starvation and eviction, for the cause of peace.

The SCLC remains stronger than many comparable regional union bodies and has maintained a principled commitment to peace. While unions in Wollongong are a shadow of their former self, their commitment to keeping Wollongong free of nuclear submarines and developing peaceful, sustainable industries is important. Their influence has been particularly significant locally, given Labor dominates local power structures at municipal, state and federal levels, in some of the safest Labor seats in the country. But while unions and Labor members may be a threat to local MPs worried about their seats, there are few signs of willingness or ability to mobilise large-scale action on the job in defiance of industrial laws as the waterside workers did in 1938. The main exception to this remains the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA).

On Dalfram Day 2024, a now annual event when local unions hold a commemoration beside a sculpture commissioned to commemorate the Pig Iron Dispute near Port Kembla harbour, a community picket was held at Bisalloy. The SCLC has opposed the Gaza war and sought legal advice for local workers concerned about their potential complicity in war crimes, but has not issued any official endorsement of the community pickets nor mobilised an official presence.

As hundreds of local people gathered at dawn outside the factory gates, a full-page advertisement funded by the SCLC appeared in the Illawarra Mercury, drawing links between the Dalfram dispute, Bisalloy, and the AUKUS submarines. Up on the headland by the harbour, SCLC and MUA officials, the Labor Lord Mayor of Wollongong, the Consul-General of China, and members of the Australian Chinese community gathered to remember a time when wharfies defied their employer and their government in the cause of international solidarity. Nearby, however, few of the workers who stood outside the gates of Bisalloy were from these traditional sectors. Rather, they represented the precarious, largely non-unionised multitude that is the class today.

The Bisalloy dispute shows that it is possible to organise militant direct action without the direct involvement of the unions, and in doing so to evade the industrial laws that have undermined union power. WAWAN has sought to work across the contradictions that exist between established working-class institutions and the precarious multitude. Its small core of activists weave together personal and organisational links to both traditional and new social movements.

When unions and anti-war activists brought thousands to the streets on May Day in 2023, in what remains the largest anti-AUKUS protest to take place in Australia, it showed that our strategy works. Nevertheless, the challenges are significant. The Labor Party’s commitment to AUKUS has proved unwavering, despite internal dissent, and the Greens recent embrace of “sovereign” arms manufacturing suggests just how limited a challenge they represent to Australian Laborism.

The anti-windfarm campaign showed how a fragmented and intensely atomised proletariat could be manipulated to support right-wing populism. Nevertheless, solidarity with Palestinians has broadened Wollongong’s anti-militarist movement beyond the more traditional red-green alliance upon which WAWAN and the earlier Green Jobs coalition were built. The Bisalloy blockades demonstrate the living potential of the social movement militancy that is needed to reconstitute a powerful anti-war movement in the coming struggles.

Alexander Brown is a Wollongong Against War and Nukes activist.