Iran: Currency shock, budget politics and class conflict

First published at Tempest.

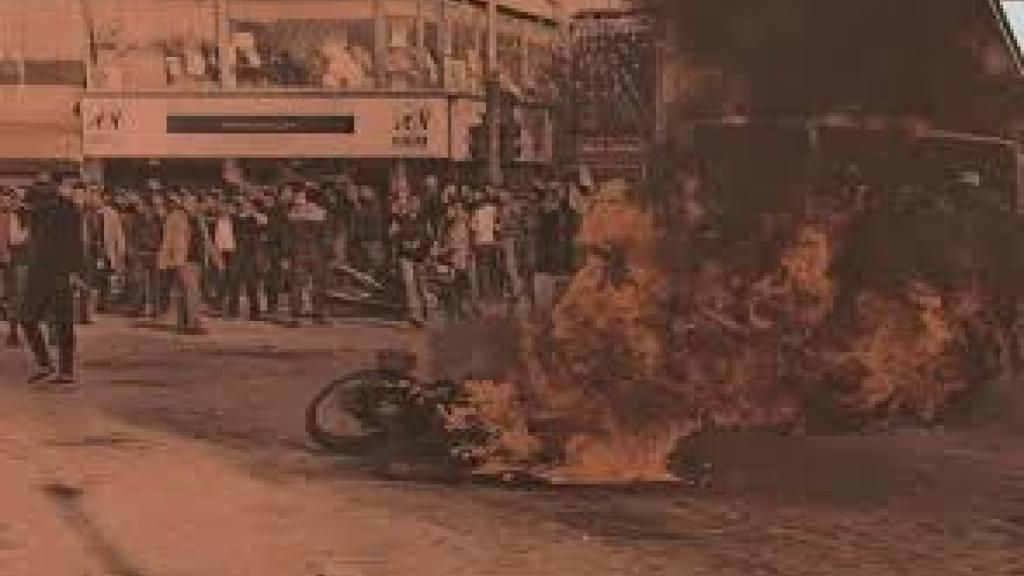

When we speak of the “Dey uprising” — Dey in the Iranian calendar roughly corresponds to late December through mid-January — it is tempting to compress the whole episode into two images: the street and repression. That shortcut serves two audiences at once: the state, and lazy analysis. The state prefers to claim it was merely “unrest,” stirred up by foreign actors and then contained through “firmness.” A segment of the opposition, for its part, prefers to describe it as nothing more than a sudden flare of “popular anger” that eventually burned out. But if we keep the story inside this narrow frame, we miss what actually mattered.

Dey was the outcome of a process. The chain began at the start of autumn — from Mehr (roughly late September) — with a combination of economic decisions, political blockages, and an internal struggle over rentier privilege and access to resources. (A rentier is someone who lives off of unearned income — “rents” — derived from investments or a powerful social position). By Dey, this accumulation reached its point of detonation, as price shocks collided with the collapse of people’s basic capacity to live: the ability to buy necessities, to plan even a few weeks ahead, to maintain ordinary dignity under extraordinary pressure.

Most importantly, the episode did not “end” simply because repression occurred. Repression was decisive, yes. But what followed repression was equally political: a reconfiguration of the regime’s center of gravity and a blunt message delivered to society. The costs of the crisis would be paid from the pockets of ordinary people, not from the wealth, immunity, and institutional power of the ruling strata.

To understand Dey, political economy must be moved from the margins back to the center of the analysis.

Why every economic crisis in Iran becomes political

Iran’s economy can be explained very simply, without heavy jargon.

On one side there is a society whose income is paid in rials and that has almost no effective tools of collective self-defense — wage workers, teachers, nurses, junior civil servants, retirees, and a large share of the urban middle strata. These groups live under inflation, become poorer as the national currency loses value, and if they protest, they often face “securitized” repression — an “intelligence case,” charges framed as national security, and the machinery of punishment.

On the other side there is a network that lives off privilege. Privilege here is not a vague moral accusation; it is a concrete set of access points: preferential access to hard currency (dollars and other foreign exchange), import and export licenses, state contracts, oil and construction projects, monopolies in transport and customs, and — crucially — judicial and security immunity. Within this network, sanctions are not only “external pressure.” They can also function as an internal opportunity: they push trade into the shadows, concentrate it in fewer hands, kill open competition, and enlarge the rents available to those with protected channels.

The result is that crisis itself becomes a mechanism of redistribution — upward.

So when the rial collapses, it is not merely the dollar rate that rises. The prices of food, medicine, rent, transportation, and energy all surge. Ordinary people become poorer, while privileged networks either profit directly or, at minimum, survive the shock far better than everyone else. That is why an economic crisis in Iran rapidly turns into a legitimacy crisis: people do not experience the state as merely “incompetent,” but as partial — structurally aligned with the beneficiaries of privilege, and willing to make society pay to preserve that order.

What exactly does “economic surgery” mean?

In Iran’s official, technocratic vocabulary, “economic surgery” is a polite label for what is essentially shock therapy. What does that mean in concrete terms?

It means the state is trying to do several things at once, and to do them fast:

- Raise energy prices — gasoline, gas, electricity — in order to cut subsidies and lighten the budget deficit.

- Move the exchange rate toward a single-rate system, or at least redefine foreign-exchange “privileges,” because a multi-tier currency regime generates corruption and creates enormous rents for those who can access preferential rates.

- Increase tax extraction, usually through taxes that are easiest to collect — such as value-added tax — and through intensified pressure on small businesses and the urban middle strata, because taxing the truly powerful centers of wealth is politically costly and often practically blocked.

- Reduce social spending, or achieve the same outcome indirectly by keeping nominal wage increases below the inflation rate — which effectively lowers real wages.

Even in a “normal” state, this package is painful for lower-income groups. In Iran, it runs into a structural problem that turns pain into political combustion: the main beneficiaries of rent and privilege are not outside the state — they sit inside the architecture of power.

So “surgery,” in rhetoric, sounds like cutting away rent-seeking and restoring economic health. But in practice it tends to become something else: austerity for society, continuity for the rentier order. The blade is supposed to cut rent; instead it usually cuts into the social body.

That contradiction — reform spoken as rent-removal, executed as downward sacrifice — is the core of Dey.

From autumn to Dey: The chain that produced an explosion

From the start of autumn — from Mehr (roughly late September) — a serious debate began to consolidate among segments of the technocratic bloc, market-oriented economists, and even parts of Iran’s decision-making circles. The core claim was blunt: A shock was necessary. Energy prices had to rise. The exchange rate had to be pushed toward a single-rate regime. The economy had to be “stabilized” through a painful, concentrated intervention. Some even sold the fantasy — borrowing from cases like Argentina — that Iran could “fix” its economic disorder without any serious change in foreign policy and without opening political space, simply by administering a hard economic shock.

But the project carried a ruthless question from the very beginning: Who would pay the price?

If the goal were genuinely to reduce rent-seeking, then the privileged networks would have to be cut back. The budgets and contracts of powerful institutions would have to come under the knife. Oil, customs, and contractor monopolies would have to be subjected to transparency and real oversight. In other words, it would require a direct confrontation with the ruling strata.

What advanced in practice, however, moved in the opposite direction: The system prepared to ensure that the shock would land on society — not on the rentiers.

It is in this context that the suppression of voices capable of explaining the crisis in class terms becomes politically legible. If the public is prevented from understanding that the issue is not simply gasoline but the distribution of power and wealth, then responding to the crisis as a national security issue becomes far easier. Arrests, the closure of critical outlets, and the targeting of social and women’s activists in the months leading into Dey can be read within precisely this logic: clearing the terrain of interpretation and organization before the storm breaks.

Then the first stage of energy price increases was implemented. The state congratulated itself for “avoiding a repeat of Aban 1398” (November 2019). But it quickly became clear that Iran’s sick economy could not be “fixed” by a single round of shock, because the problem was never only the price of gasoline. The deeper drivers were structural: chronic budget deficits, sanctions, networked corruption, and a privilege-based rentier economy. So the talk of a second, deeper shock returned — and this was the point at which a technocratic project became a political crisis.

Why? Because two things were happening at once.

On the one hand, officials pushed the idea of creating at least the horizon of negotiations with the United States as a way to calm the foreign-exchange market. Even the mere possibility of talks can reduce psychological pressure on the rial, for a time. On the other hand, the state’s confrontational foreign policy posture and its domestic political closures remained intact. In other words, the system wanted to intensify austerity without accepting even minimal institutional reform. “Surgery” had to be performed, but the blade was permitted to cut only into society — never into the body of power.

The 1405 (2026-2027) budget, in detail: A document that said, “You will pay the price”

On 23 December 2025 (2 Dey 1404 in the Iranian calendar), the government submitted the draft budget for 1405 — and many things that had previously circulated as “speculation” suddenly hardened into an official document.

To make sure the reader understands exactly what is being discussed, several key pillars — and the logic behind them — have to be spelled out plainly.

(a) Wages versus inflation: A built-in pay cut

The budget assumed a nominal rise in wages and salaries at a level that does not match Iran’s existing inflation. If inflation is above 40 percent while wages rise by 20 percent, the implication is straightforward: real purchasing power falls.

Put simply: if this year your salary allowed you to buy 10 kilos of meat or 20 kilos of rice, next year — despite the “raise” — you will be able to buy less. The state is effectively closing its fiscal gap by shrinking the real wage of employees and wage earners. (In technical terms, a 20 percent nominal increase against 40 percent inflation is roughly a 14 percent drop in real terms: 1.20 ÷ 1.40 ≈ 0.86.)

(b) Minimum pay and the living basket: Working poverty as a policy outcome

The budget’s projected minimum wage level was far below the real cost of living. When the estimated cost of a working-class household’s basic living basket runs into tens of millions of tomans, but the minimum wage remains well below that threshold, the result is not mysterious: wage poverty. (Figures in Iran are typically discussed in tomans — with the “Iranian type” of everyday usage — though any conversion to U.S. dollars depends on the volatile free-market rate.)

That means poverty is no longer merely a condition of unemployment. It becomes something you can experience while fully employed — a structural feature of the system, not a personal failure.

(c) Taxes: Raising revenue where it’s easiest, not where it’s fairest

The draft budget projected a sharp increase in tax revenues. In practice, the most “collectible” taxes tend to be extracted from the middle and lower strata, because taxing the most powerful centers of wealth is either politically blocked or met with intense resistance.

The increase of VAT (value-added tax) from 10 percent to 12 percent is a clear example. This is a tax that lands on everyday consumption — on the receipts of ordinary life — not on rentier windfalls. In effect, it is the population’s daily purchases, not privileged profits, that are being asked to finance the state’s crisis.

(d) The operating deficit: The state cannot fund itself by normal means

The budget also pointed to an operating deficit on the scale of hundreds of trillions of tomans — a number that may sound abstract, so it should be translated into meaning:

It means the state cannot cover its routine expenditures through routine revenues. To bridge that gap, it must do one (or several) of the following:

- print money or monetize the deficit, feeding inflation

- raise taxes further, intensifying pressure on society

- sell assets and issue debt, pushing the burden into the future

- draw on public funds and reserves, consuming what is left of collective resources

In other words: When the deficit reaches this magnitude, economic management becomes inseparable from political conflict — because every “solution” has a social class that pays for it.

(e) The budgets of powerful institutions: Untouched, or minimally touched

At the same time, major allocations linked to military, security, and ideological institutions remained intact or relatively shielded. That is the budget’s political message in its most condensed form:

(f) Austerity for the lower strata; stability for the core of power.

Once society sees that combination in black and white, the issue is no longer “just gasoline prices” or “just inflation.” The issue becomes something more fundamental: the state has formally announced that the costs of the crisis will be extracted from the market, the middle strata, and the poor — not from the ruling network that holds wealth, immunity, and institutional leverage.

This is how a budget stops being merely a financial document and becomes a legitimacy document — or, more precisely, a document that accelerates the collapse of legitimacy.

The bazaar, trust networks, and holdings

In the classic narrative of modern Iran, the bazaar is often described as one of the pillars of the political order—an institution with social weight, organizational capacity, and historical leverage. But the reality of the last two decades is different: the traditional bazaar has steadily lost much of its structural power in the face of giant holding companies, quasi-state economic headquarters, financial and credit institutions, major contractors, and sanctions-shaped semi-monopolistic networks. The bazaar still matters as a capillary system for distributing goods and as a social terrain, but the real centers of economic decision-making have, for a long time, been located elsewhere.

When a foreign-exchange crisis intensifies, the traditional bazaar is typically the first part of the economy to freeze. It cannot price goods with confidence. It cannot buy inventory without fearing immediate loss. It cannot convert stock into reliable money. In contrast, trust (cartel-like) networks and larger connected actors — those with protected channels and privileged access — often have far more room to maneuver.

This produces a contradiction inside the economic order itself: a segment of the traditional economy becomes paralyzed under the pressure of currency collapse, while powerful sanctions-era networks either profit from instability or at least manage it more effectively than everyone else. The crisis is not simply “the state versus society.” It is also a struggle among different fractions of the system over who gets to survive the shock, and who gets crushed by it.

So when protest begins in the bazaar and rapidly jumps to the university — and then to smaller, poorer towns — this is not evidence that the “bazaar” suddenly became revolutionary. It is evidence that society was already primed, and that a rupture inside the economic order opened a corridor. That is the qualitative difference that matters: The spark may emerge from a central node of the traditional economy, but the fuel is drawn from the entire social landscape.

The social composition and geography of the revolt: From the center to the periphery

Dey was not a neat, uniform coalition — and that is precisely why it matters. Real movements are rarely orderly. They are noisy, multi-voiced, and cross-class. In this wave, several poles stood out:

- Small business owners and the bazaar, being crushed by currency instability, heavier taxation, and recessionary conditions.

- Students and younger people, carrying the memory of Woman, Life, Freedom and increasingly tying questions of dignity and freedom to the everyday crisis of livelihood.

- Workers and wage earners — teachers, nurses, retirees, and others who have been living inside continuous cycles of protest for years, not as a sudden awakening but as an accumulated experience of wage poverty and institutional contempt.

- Smaller and poorer towns, which have repeatedly shown in previous waves that when they erupt, repression often becomes more naked — more direct, less mediated, and more lethal.

- National-minority regions and other marginalized peripheries, where informal economies and double repression are lived simultaneously: economic dispossession on one front, and on another, intensified repression in the name of national security.

The crucial point is this: the linkage from bazaar to university, and then outward to smaller towns, demonstrated that the rupture was not only class-based. It was also generational and regional. Yet these fractures rotated around a single axis: the systematic removal of people from decision-making, and the consistent strategy of forcing the social costs of crisis downward — onto those with the least power to refuse them.

Fractures within the power bloc

In the months leading into Dey, fractures inside the ruling bloc became more visible. Some technocrats and political figures openly pointed to the need for negotiations as a way to reduce pressure on the foreign-exchange market — essentially, to create a stabilizing horizon for the rial. Meanwhile, parts of the economic oligarchy showed little willingness to sacrifice their interests: they resisted government demands to return offshore or hoarded currency to domestic circulation, or to alter the practices through which they protect their profits. The judiciary, in many cases, effectively reinforced this hierarchy of power — speaking far more softly to major capital holders than to workers, protesters, or ordinary defendants swept into “national security” cases.

But these internal conflicts tend to converge at a single point: the street. Once mass protest breaks open public space, rival factions recognize a shared danger. The disagreements over how to manage the rentier order may continue, but repression becomes the common project. In other words: divisions over the distribution of rents remain; unity over coercion hardens.

External actors and the exiled right wing

In moments of crisis, external players inevitably move. Foreign states pursue their own interests, not the freedom of Iran’s people. The exiled right, meanwhile, often revolves around one central idea: gaining power from the outside — through deals, lobbying, and reliance on foreign pressure.

That approach carries two major dangers:

- It hands the state a narrative weapon. The regime can portray protest as “dependent,” paint dissent as a foreign plot, and use that framing to legitimize repression.

- It diverts society away from internal organization and toward the fantasy of a savior — an expectation that political change will arrive through a “rescuer,” rather than through collective power built from below.

Dey showed how destructive this expectation can be. It fractures the movement, turns strategy into factional theater, and shifts the center of gravity away from concrete demands — wages, the right to organize, women’s freedom, social justice — toward symbolic battles that are easier to manipulate, easier to co-opt, and easier to weaponize against the uprising itself.

Bonapartism against revolution

Here the concept of Bonapartism becomes analytically useful — but only if it is stated in clear, accessible terms.

In the Marxist tradition, Bonapartism names a situation in which social antagonisms and political crisis become so acute that the state—above all its military and administrative apparatus — presents itself as an “arbiter above classes.” It claims that society is fragmenting, that forces are locked in destructive conflict, and therefore a concentrated authority is needed to restore “order.” But this arbitration is not neutral in practice. Its real function is to preserve property relations and the interests of the dominant strata, even if the external form of rule changes.

Translated into the language of Iran today, Bonapartism looks like this scenario:

First, the crisis is contained through mass violence and communications shutdowns — killing, arrests, and the deliberate severing of society’s ability to document, coordinate, and sustain collective action. Then, once the street is forced into retreat, the system pivots toward a political reconfiguration and elevates a figure — or a structure — marketed as a “savior,” designed to divert society away from the path of social revolution.

That “savior” can wear different costumes. It can appear as a technocrat, calling the project “economic reform.” It can appear as a military strongman, branding it “national security.” It can even appear in monarchist form, selling it as “historical salvation.” The common denominator is always the same: none of these routes touch the real foundations of the rentier order — property, privilege, and the networks of immunity. They merely change the management style and, once again, shift the costs onto society.

If we read Dey through this framework, repression in the name of national security is not merely a reflexive response to protest. It is part of a broader strategy: weakening society, suspending the possibility of revolutionary transformation, and preparing the terrain for “order from above” — an order that may stabilize the ruling network while leaving Iran structurally weaker and its social majority more exposed.

Siyavash Shahabi is a journalist and political activist currently living as a refugee in Athens, Greece, and the author of the blog FireNextTime, which focuses on labor movements, migration, and social struggles, especially in Iran.