Renewing the Left: Not just doom and gloom

First published at Amandla!.

This article seeks to respond to the questions posed by Amandla! which relate to the South African Left in particular: where is the Left intellectually, programmatically and organisationally? What has happened to it, and why has it become so fragmented and marginal? Given the broadness of the questions, it is necessary to engage with them within a particular timeframe. Therefore this article is located in the post-apartheid political moment.

Setbacks of the transition

The negotiations that culminated in the 1994 elections marked the end of legal apartheid in South Africa, and that certainly marked a turning point in the struggle for liberation. In the immediate phase of the transition, the ANC government set about dismantling the institutions and the legal frameworks that upheld apartheid. They introduced a new constitution and a battery of new policies and laws. The ANC has striven to dismantle apartheid’s racialised structures and institutions. But it has failed to change the economic structure and ownership patterns underpinning the system of racial capitalism. Rather, according to Neva Makgetla in the Review of African Political Economy in 2004, “the state separates anti-poverty measures from its economic policy, treating them purely as assistance for the poor rather than as an integral part of its growth strategy.” She further argues that the ANC has “underpinned measures to free up markets through deregulation and privatisation, and to encourage foreign investment through conservative fiscal and monetary policies.” In 2002, in An Ordinary Country, Neville Alexander commented on the ease with which the ANC accepted compromise: Almost everything that had formerly been propagated as sacred cows has proved to be expendable. Most notable among these was the policy of nationalisation of the mines and of monopoly companies.

In a relatively short period of time, and with little popular opposition, the ANC shifted from a progressive Keynesian programme of “Growth with Redistribution”, the RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme), to the trickle-down economics of the neoliberal Gear (Growth Employment, and Redistribution). And in 2012, under the presidency of Zuma, which we should not forget was the great hope of the left of the Alliance, adopted the National Development Plan (NDP), which represented a further slide down the neoliberal rabbit hole. The NDP argued for minimal state intervention, maintaining existing patterns of ownership and control of the economy, and the deregulation of the labour market.

The only policy that the ANC has advanced towards transforming the economy is black economic empowerment (BEE) which is nothing more than an attempt to create a black bourgeoisie on the margins of the economy. The shift to neoliberalism itself did not represent a defeat for the Left. But this dramatic shift in policy did not provoke sustained mass resistance.

The break in the Alliance and the ANC itself put the working class movement and the Left on the defensive. The euphoria of constructing a “New South Africa” demobilized and hollowed out mass movements, civics, youth and community groups into a range of “cogoverning/social contract” structures such as community police forums, health forums, development committees, Nedlac and ward committees. These processes dislocated and weakened the mass movement and tended to isolate the Left. However, even the Left (outside the Tripartite Alliance) were also drawn into policy making forums and absorbed into senior management in the academy and public institutions. Left formations were turned into spectators and mere commentators in the unfolding transition process from apartheid.

The complicated task confronting the Left in South Africa was that, in just three short decades after apartheid, it had to confront a society which had become the most unequal in the world. It had one of the highest levels of unemployment, linked to growing impoverishment, endemic corruption, and collapsing social services rendered by dysfunctional and bankrupt municipalities. This has given rise to a social crisis where the very social fabric in working-class communities is collapsing. This undermines the capacity of those communities to mobilise solidarity, especially in the face of the extreme violence against women and children, gangsterism and substance abuse. Under these conditions, and with the legacy of spatial apartheid, communities have turned in on themselves, making it very difficult for local organizing to flourish.

Possibilities and challenges in rebuilding

Notwithstanding these major setbacks, workers and working-class communities continue to struggle and resist. A range of new popular organisations and new generations of activists are organising on a number of fronts throughout the country. While many of these formations are very localised, they are important in terms of rebuilding the mass movement. They represent autonomous structures led by a new generation of activists, who have not been absorbed into the ANC machinery or the Tripartite Alliance structures. They are potentially able to link their local issues to broader national concerns, such as austerity, privatisation and commodification of services. They constitute a layer of activists available to be drawn into radical politics. In regard to regenerating Left politics, the student terrain has proven to be very important in the history of radical politics in South Africa and internationally. For a long time, student politics has been dominated by ANC- and SACP-aligned formations.

Yet the most significant struggle and movement of tertiary students post-apartheid occurred in formations in #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. Both #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall were united fronts of students coming from different political currents or no political current. In the absence of an independent left formation, it was the EFF which was able to attract a large number of the students radicalised during the course of this struggle. However, #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall also highlighted that radical intellectuals at the universities were either completely absent or at best present in relatively small pockets. Many of the “radical intellectual layers” of the apartheid period, such as Adam Habib and Ihron Rensberg, now manage the universities, pitting themselves against the movements. In terms of generating ideas, in the days of apartheid, the universities were places where socialist and Marxist politics played an influential role much beyond the confines of academia.

Today, post-modernism and identity politics have come to dominate at our tertiary institutions. Workers have undertaken important struggles and strikes in relation to capital and the state’s attack on workers, most of which have been outside the Cosatu fold. The 2012 mass strike of mineworkers and farmworkers are cases in point. These struggles were heroic. Workers challenged capital against great odds, as strike actions and rebellions lasted for weeks, even months. Most actions were self-organised, and this should have been the basis for the regeneration of the bureaucratised trade union movement. That this has not occurred is a further indication of the weakness of the socialist Left.

The future direction for socialist activists in the labour movement lies in rank and file organising, fighting for democracy and the right to organise around different political views. In terms of thinking through strategies for rebuilding the Left, these local struggles of popular movements, the struggles of the students and the mass strikes of mine and farm workers must be celebrated. This is especially the case bearing in mind the capacity for self-organisation in these struggles. The failure of the struggles to generate a new anti-capitalist programme and political organisation indicates the critical role for the nascent Left in this country.

Rebuilding and reorganising of the Left

Given both the objective situation and the challenges confronting the rebuilding of the mass movement, the situation in the country shouts out with great urgency for a left alternative. Such an alternative would be able to link, generalise and politicise the resistance to capital and the state.

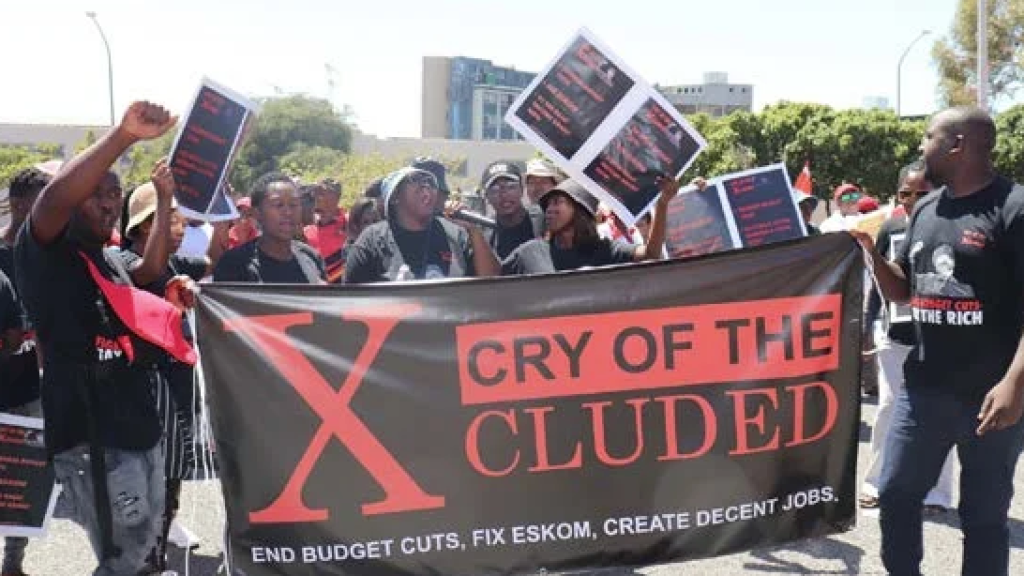

Tragically, all that South Africa has produced are hundreds of electoral parties, with limited roots in the working classes, and equally limited political agendas, other than a strong desire to have a path to lucrative paycheques for those elected. This is the context for this review of the several failed attempts at left regroupment which have been undertaken in the post-apartheid period. The Anti-Privatisation Forum and the Social Movement Indaba pointed to interesting processes which brought popular movements and different left currents together in struggle. This was later taken forward by the formation of the Democratic Left Front (DLF) in 2008, as an explicit political movement open to movements and individuals.

The DLF united social movements, community organisations, small left parties, labour unions and popular working-class formations from a broad ideological spectrum, in an anti-capitalist Left. It played a key role, rooting its organisation in social struggles of the working class, such as housing and decommodified services, especially health and for climate jobs. It also advanced the perspective of feminist-eco-socialism in response to the reproduction of racial capitalism. It presented itself as a radical alternative at the very moment the Left in the Tripartite Alliance was celebrating their supposed breakthrough in getting Zuma elected as the left alternative to Mbeki’s neoliberalism.

The 2013 Numsa Special National Congress opened a new movement for the regroupment of the Left, especially with its convening of a United Front. The DLF recognised the importance of this initiative. It offered an even greater scope for creating a common platform between labour, social movements and the broad Left. Tragically, the United Front failed, largely because the Stalinist leadership around Irvin Jim feared losing political control of it. Their political aspirations were channeled into forming the Socialist Revolutionary Workers Party (SRWP) as a radical version of the SACP. Its failed electoral effort of 2019 has condemned it to the margins of politics and placed a seal on the Numsa moment’s real possibilities for renewing left politics.

For those seeking to fill the vacuum of the Left, it is necessary to come to terms with the EFF. This is the only left formation which has managed, not only to develop a mass working-class base but also to successfully win representation in Parliament and local government. Its radical nationalism and strident race politics have led some of the Left to mistakenly characterise the EFF as a proto-fascist movement. In reality it is a cross between a radical ANC and an antineoliberal activist SACP. Given the popular base, but of the EFF, it will not be possible to wish them away. A new left politics will have to engage and seek alliances with the EFF, even as it guards its independence and focuses on building itself.

A long march

The global situation is dire, with the rise of right-wing populism, growing geopolitical tensions between competing imperialisms, the cost of living crisis, austerity and waves of retrenchments. No doubt, the Left globally and in South Africa face challenging times. It is almost 30 years since the end of apartheid. We are at the brink of the climate catastrophe. We are the most unequal country in the world, where colliding economic, environmental and social crises amplify the intensity of each other. We cannot approach politics with complacency. The intersection of racial, gender and class oppressions in post-apartheid South Africa further complicates understanding the essential nature of the system we are dealing with. It makes difficult the task of elaborating a comprehensive emancipatory programme and strategy for power.

Knowing the scale of the challenges we face is a necessary precondition for renewing an eco-socialist, eco-feminist politics. It has to be approached as a long march, avoiding shortcuts and opportunistic quick fixes. However, basing ourselves on the rich and significant legacy of left politics, on the ongoing struggles of poor and working-class people, and on the new movements and ideas these struggles have produced, will make the task less daunting.

Mercia Andrews is a member of Dialogues for an Anti-Capitalist Future, and a socialist-feminist activist organising in rural and land reform movements.