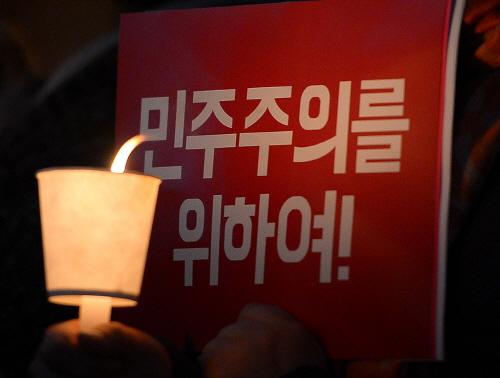

South Korea's candlelight revolution

By International Strategy Center

February 8, 2017 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from International Strategy Center with permission — Sitting in Gwanghwamun square on December 31, the screen rapidly dialled up to 10,000,000 as it added up the number of participants in the past ten candlelight protests. Every Saturday evening for the last two months of 2016, people had come out in the streets calling for impeachment. A few weeks prior, an impeachment motion had been passed in the National Assembly by an overwhelming vote. We were saying goodbye to the year with a candlelight protest on New Year’s Eve complete with Christmas jingles about impeachment.

The rally was followed by two separate marches, one to the presidential Blue House, the other to the constitutional court: a reminder that, whether villain or hero, the judges too were actors in this candlelight story. Yet, the protagonists resided not in the halls of power, but in the streets holding candles.

Now, a month, and three candlelight protests later, as the special prosecutor gears up to question President Park and the constitutional court sets a March deadline for its verdict, the candlelight protests are achieving what many thought impossible: impeachment of the president. In the process, the candlelight revolution is transforming Korean democracy and its people.

It was the candlelight protests that pushed politicians past the safeguards of the status quo and emboldened/pressured them to represent the will and outrage of their constituents. The candlelight protests began with demands for President Park’s voluntary resignation. As evidence for abuse of power, leaked state secrets, and bribery mounted against her, and as it became clear that neither a million, nor two million people protests were enough for her to step down, the chants for resignation changed to impeachment and incarceration.

However, elected representatives lagged behind public opinion and will. In fact, faced with the tremendous task before them, the opposition parties grew timid, then wavered when politically expedient solutions presented themselves. The first instance was at the beginning as the scandal was unraveling. Park proposed that for the sake of returning the country to normality, she would allow the National Assembly to nominate a new prime minister with extensive powers in domestic affairs. The main opposition party - the Democratic party - wavered. Phone blitzes from the public later, they returned back to the popular demand of resignation.

As it became clear that President Park would not step down no matter the political cost or size of the candlelight protests, calls for resignation turned into impeachment. As public outrage swelled to nearly 2 million, the opposition parties jumped on the impeachment bandwagon. Yet, just before the impeachment motion was to be introduced, the second carrot was dropped and dangled before them: President Park, in a public address, introduced the possibility of voluntary resignation by April.[1] The anti-Park faction of the ruling party that had abandoned ship and had plotted a course towards cooperation with the opposition parties now was shifting towards the April voluntary resignation. Faced with the prospect of insufficient votes (without the anti-Park faction votes) for approval of the impeachment, the opposition wavered. The people mobilized: they blitzed the phones of individual Saenuri Party members and protested outside their offices. Even the opposition that had grown timid was dragged back to the front of the impeachment struggle.

Then that Saturday, 2.3 million people came out insisting on either an immediate resignation or impeachment. By Monday, the politicians had changed: the opposition party members had grown bold in their pursuit of impeachment, even holding mini-rallies; the anti-Park faction was once again speaking about impeachment; and even the pro-Park faction made the crucial decision to allow members to vote at will. Thus, 234 assembly members voted for impeachment, far exceeding the necessary 200. Not only had the anti-Park faction voted for impeachment, so had many from the pro-Park faction.

With the president stripped of her powers during the impeachment, the special prosecution [2] no longer faced the daunting task of investigating a president will full powers. Kim Jong-min, chair of the Seoul branch of the Justice Party, notes: “The prosecutor has the power to search and to summon people for interrogation. Yet, until now they have always been careful of those in power. But this special prosecutor doesn’t have to do that. That’s because of the candlelight protests.” While the special prosecutor’s investigation is separate from that of the constitutional court, the former’s findings still impact the latter’s verdict.

The Choi Soon-Sil scandal may have initiated the process, but the impeachment process has not just been about Park’s misdeeds with Choi Soon-sil. The candlelight protests created a space to revisit Park’s other misdeeds, in particular her deadliest: the Sewol ferry accident that killed 304. Not only was the rescue under her watch a perfect storm of incompetence and negligence, but the investigation that followed was also plagued by repression and cover-up by a Park administration unwilling to reveal the truth or learn its lessons. Despite its gravity, the Sewol ferry tragedy did not just naturally appear in the impeachment motion.

Yoo Kyung-geun, a father of one of the high school victims and chair of the 4/16 Sewol Families for Truth and a Safer Society, relates how the families kept the Sewol issue afloat when the protests first broke out: “When the Choi Soon-sil scandal first broke out, we were afraid that it would simply drown out the issue of the Sewol. So, we took a very bold and desperate gamble. In the first candlelight protest, we gathered and chanted that President Park should be incarcerated and that they 7 hours after the Sewol ferry should be investigated. We were very nervous about a backlash, but we took the chance anyways because we were so desperate. While everyone was chanting that the President step down, we were the only ones chanting that she be imprisoned. On the next protest, it wasn’t just us that started protesting, it was also those around us. By the third candlelight protest, people on stage started calling out for her arrest.”

Despite the growing calls for an investigation to the seven hours following the Sewol ferry accident, the opposition parties hesitated in placing it in the impeachment motion. “Three days before the motion was introduced a member of the opposition called me, ‘Isn’t the impeachment important? The anti-Park faction won’t vote for impeachment because of this provision, couldn’t you please understand our situation? Maybe we could pursue the investigation [to the Sewol tragedy] later',” recalled Yoo. His answer was resolute. They would not accept an impeachment motion without the Sewol issue. In fact, they would actively protest any motion without it. The Sewol was included in a motion that passed amidst the flickering lights of 2.3 million candles.

Having witnessed the candlelight protests first hand, it becomes clear that it is not just about impeaching President Park but also about transforming Korean democracy and people. People came out in the hundreds of thousands and millions to sit on the pavement in sub-zero temperature. They came out with their unions and organizations. Many simply came out with their families and friends. Students ranging from elementary to university came out wearing their school uniforms stirring the imagination about the collective education on democratic action for the next generation. The stage that facilitated this transformation are massive productions, on the scale of outdoor rock festivals: multi-screens so that millions can see and hear the stage, chants prepared in advance, hundreds of thousands of candles, lists of performers and speakers, and the organization and logistics of the marches that follow. The productions were carried out by the People’s Emergency Action to Bring Down President Park, a coalition of 1,500 groups that came up with the chants, line-up of performers, and set the stage. Ahn Jin Geol, a standing member of the operations committee, explains that the chants come from the grassroots up through their network of 1,500 groups.

Being at the protests, it’s clear that they are different in character from previous ones. While the chants are militant, the songs that play are not the same militant songs usually heard in protests. Rather, they are rock concerts, from reggae rock to ballads. They not only entertain, but they also move and touch. “The change started on November 5 and 12 as the singers came out, as families came out with their toddlers, as students came out. The space became firmly established as a cultural night.” The second moment was when the organizers succeeded in marching peacefully to up to 100 meters of the Blue House. “The performances were moving, and we were going strictly by the law in the march and creating a peaceful atmosphere,” explains Ahn.

The constitutional court has announced it will deliver a verdict before March 13. All signs and evidence point to an impeachment, which means that a presidential election would be held by May. Yet, a new president is not enough. “We can’t just demand a change in government, but we must call for deep fundamental reforms,” expresses Kim. How far this candlelight revolution goes will be determined by its protagonists.

Special thanks to Kim Jong-min Chair of the Seoul Branch of the Justice Party, Ahn Jin-geol General Secretary of People's Solidarity for Participatory Democracy and an a standing member of the Operations Committee of the People's Emergency Action to Bring Down President Park, Yoo Kyung-geun, chair of the 4/16 Sewol Families for Truth and a Safer Society, and Kim Sang-gyun (former producer at MBC).

Notes

[1] An April resignation would have created a whole different set of conditions then the current one. The special prosecution would have had to carry out their investigation against an acting president with full powers, as opposed to one stripped of her powers.

[2] The constitutional court and the special prosecutor are both part of two different processes. The constitutional court became involved after the impeachment motion was passed. The special prosecutor became involved after a special bill approving him on November 17. While the constitutional court determines whether the president violated the constitution in her role as president, the special prosecutor conducts a separate investigation. While both undoubtedly influence each other, they are part of two separate spheres.