United States: Barre’s hidden history of Italian-American radicalism

By Kate Frey

February 23, 2018 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal — Barre, located in central Vermont, not far from the capital, Montpelier, with a population of 8710, was for a time in the early 1900s an internationally known center of Italian-American radicalism.

The city was founded in 1788 as a farming community and was named after Issac Barre, a British politician who supported the American colonies in the period leading up to the Revolutionary War. Vermont is known for rocky soil and a cold climate, making farming difficult and many of the first generation of settlers eventually moved away.

Large granite deposits were discovered shortly after the War of 1812 and Barre’s first granite quarry opened in 1813. Vermont’s hilly terrain made transporting granite difficult though and it wasn’t until the Central Vermont Railroad ran a spur into Barre in 1875 that the granite industry took off.

Large numbers of immigrants, mostly skilled granite quarry workers and stone-cutters, began arriving in 1880. The population of Barre rose from 2000 in the 1870s to 12,000 by 1910. Skilled stone-cutters and quarry workers originally came from Scotland, then Spain and later predominately from northern Italy. By 1910, Italians has supplanted the Scottish as the largest immigrant community in Barre and by 1914 one quarter of Barre’s population was Italian, making Barre Vermont’s foremost ethnically mixed blue collar city.

The Italian immigrants who came to work in Barre differed from those from southern Italy who settled in other regions of the US, who were generally from a peasant background and were less likely to be literate. Barre granite workers were generally literate, had often traveled or lived in other parts of Europe connected with the stone industry such as Spain, France, and Russia. They often had connections with radical politics and were often very hostile to the Catholic Church, which they had seen as supporting the large landowners and the corrupt status quo in Italy.

After the reunification of Italy, the Risorgimento in 1871, stone quarries in northern Italy began shutting down due to foreign competition, creating mass unemployment. This was blamed by many workers on Italy’s recent reunification. This encouraged emigration. Italian immigrants brought radical traditions with them to Barre. According to an interview by the oral historian Robert Colodny with an old time granite worker in Vermont’s Untold Story, over a dozen members of one of Garibaldi’s expeditionary forces settled in Barre as did followers of the Italian revolutionary Mazzini.

By 1905 Barre had about 2000 granite workers with about 1400 of them skilled stonecutters. With a blue collar, working class majority and a large immigrant population, Barre was typical of late 19th/early 20th century US cities. However, the fact that Barre had become the world’s largest supplier of granite made the city unusual. With Barre having a monopoly on granite production, its workers, after much struggle and a high degree of militancy, were able to win victories and higher wage rates than workers elsewhere in the US.

Conditions for Barre’s granite workers were horrendous and far worse than those of granite workers in Europe. Granite contains much higher levels of deadly silica fibers than marble, which most stone workers had previously worked on in Italy, and stone workers in the US worked in indoor, confined spaces, different from the practice in Europe. Stone-cutters often worked without filters. Silicosis, a respiratory disease which was often called “stonecutters tuberculosis” was very common, leading to health problems and a high death toll among workers.

In 1900 the average life expectancy in the US was 50 – in Barre it was 42. According to “Solid Men In The Granite City; A History of Municipal Socialism in Barre, Vermont, 1916-1931” by Robert E. Weir, Barre stoneworkers had a 33% higher mortality rate than the US as a whole well into the 1940s and conditions in the industry only really improved with the passage of the Occupational Health and Safety Act in 1970. Weir cites oral histories and personal letters showing that the stone cutting industry was considered a killer. Weir quotes a long time granite worker, Roaldus Richmond as saying, “I cut stone all my life and drank all my life. Both will kill a man in his forties”.

Union militancy

A small granite strike in 1903 was followed by a bigger strike in 1904, when 3000 workers were locked out in response to a tool sharpeners strike. Four thousand five hundred workers went on strike in 1908 and there were walk-outs in 1909-10, 1915, 1922, 1933 and 1938. A big labor action occurred in 1922 when workers walked out in reaction to Barre businesses attempting to impose the anti-union “American Plan” on employees.

From 1900 to 1917, when union membership in the US was no more than 7%, about 90% of Barre’s workers belonged to unions While Barre workers belonged to a variety of unions, the two dominant unions during the early 20th century was the moderate Granite Cutters International Association (GCIA), which was affiliated with the AFL, and the more radical Quarry Workers International Union (QWIU). The QWIU, headquartered in Barre, had at one time been a part of the Socialist Labor Party, then affiliated with the IWW, and although eventually joining the AFL remained dominated by anarchists, who frequently clashed with the AFL.

The granite industry was divided into two sectors, quarrying and the more skilled finishing work. In Barre the industry was not dominated by large monopolies and trusts, as was much of late 19th century industry, but rather by dozens of relatively small-scale quarries and shops, many of which had been started by former workers in the industry. The largest firm in the early 1900 employed 500 workers and the next two largest employed 60 workers, and 25, respectively.

Robert E. Weir in “Solid Men In the Granite City”, said experienced cutters made about $2.50 a day and often felt closer to so-called “self made” employers than they did with the more elite carvers and finishers who earned twice that amount, a high wage for that era. Weir says that even during strikes lower paid workers would tend to focus discontent on individual employers rather than the capitalist system itself.

The dynamics of the granite industry, including horrendous working conditions, the decentralized nature of the industry, combined with radical traditions from Europe, tended to reinforce anarchist traditions rooted in the individualisms of artisans and small producers over that of broader working class oriented socialism. An article in the VT Digger, “Then Again, A Voice for Change” by Mark Bushnell, says about Barre: “At the turn of the last century, sections of the city were consumed with anarchism”. Groups of Italian anarchists also existed in the nearby towns of Montpelier, Northfield, and Hardwick, although Barre had the largest anarchist community. Barre’s anarchists were characterized by lively debates and fierce polemics.

Emma Goldman

The anarchist Emma Goldman made several, highly tumultuous, trips to Barre. Her first trip was in January of 1899 and was to be part of a nine month, 11 state speaking tour. Her first visit started off well. Barre Evening Telegram announced she would be speaking on social problems and called Goldman “the well-known lecturer and friend of the people” and this favorable announcement was echoed by Barre’s six Italian language papers. She stayed with Salvatore Palavicini, an anarchist activist whom she had worked with during a textile strike. She also visited Luigi Galleani, a highly controversial insurrectionary anarchist.

Beginning January 23, Goldman spoke on women’s rights and the need to broaden opportunities for women at Barre’s Tomasi Hall. According to reporters she spoke to a packed hall, with between 40-50 women present among a crowd of mostly male workers. This speech, while progressive for the time, was relatively uncontroversial. A reporter for the Telegram said that Goldman “gave a very interesting discourse, speaking eloquently in defense of her sister woman.”

Goldman’s lecture a few days later was much more controversial, although it is not known what she said. According to some accounts she had said, “God bless the hand that blew up the Maine” referring to the US Navy ship that had blown up in Havana harbor the previous year, killing 260, although she herself hotly denied saying this. Before she could make her third scheduled speech at Tomasi Hall, a large crowd of people, according to some accounts verging on a mob, gathered in front of hall, determined to prevent her from speaking. There was a threat to cut the electrical cables, leaving the hall in darkness, if she spoke. Anarchists came in a show of counter-force and according to a contemporary newspaper account everyone was “armed to the teeth and some of the anarchists of Barre were ready to make their presence felt”. The town sheriff and his deputies surrounding the hall and closed down the event.

Goldman subsequently left Vermont for Chicago, the next stop on her lecture tour. The Montpelier Telegram said, “if the woman keeps away from Barre or stops talking, no one is likely to make trouble for her”, carrying an implicit threat. Unlike her earlier speeches, a transcript of her canceled speech exists, which ironically was about how authority restricts freedom. While Goldman could not deliver her speech, Barre anarchists printed 5000 copies of it and over the next several days widely distributed them around town. In her abortive speech Goldman said she wasn’t attacking society but the state and its laws which she thought was oppressive and hypocritical. She emphasized how government works on behalf of the rich while waging gruesome wars and subjecting the poor to imprisonment and the death penalty.

In her autobiography Goldman later said that a friend from Barre had told her that the police pressured her to leave town not because of hostility from townspeople after her radical speech but because, in one incident, she had caught Barre’s mayor and chief of police dead drunk and had knowledge of their stakes in the local prostitution racket. Weir however says that story doesn’t seem likely, stating that although Vermont had been a “dry” state since 1854, when the state enacted its own form of Prohibition, this was widely ignored by many towns in Vermont, and Barre residents would not have been at all surprised to see town officials drunk.

In December of the year after Goldman’s first appearance in Barre, stemming from long simmering tensions between Barre’s anarchists and the police, Barre Police Chief Patrick Brown was ambushed by six anarchists and shot. He survived the attack. At least one Barre anarchist was convicted in the shooting. The Vermont State’s Attorney tried to charge Goldman as an accessory, claiming that she had yelled threats against the police from her departing train. A grand jury found the charge unconvincing and refused to indict her. Brown was the same chief of police whom it was claimed Goldman saw drunk in 1899.

In 1902, after a mentally ill man, Leon Czolgosz, who had allegedly been a follower of Goldman, assassinated President McKinley, the Montpelier Evening Telegram called for the assassin to be hung and hinted at similar punishment for Goldman, saying, “perhaps it would seem a little barbarous to lynch a woman, but Emma Goldman certainly deserves something severe in the way of punishment.”. Goldman hotly denied having any connection with Czolgosz or the assassination.

Despite the intense hostility against her, Goldman visited Barre to a couple of more occasions, in 1907 and 1911. These appearances do not appear to have been as controversial or inflammatory as her first appearance.

Luigi Galleani

A major figure in the Italian-American anarchist movement and Barre resident was Luigi Galleani (1861-1919). Between 1914-1932 his followers carried out a series of bombings against institutions regarded as pillars of US capitalism. While misguided and counterproductive, it is important to keep in mind that this was a highly corrupt, violence-prone era when strikes in general were subjected to routine police violence and National Guard or private armies carried out massacres of striking workers at places like Ludlow, Colorado and Homestead Pennsylvania. The capitalist system itself was seen as a violent enemy of working people.

Born in Vercelli, in the granite region of northern Italy, Galleani became an anarchist while studying at the University of Turin. Wanted by Italian police for his anarchist activism, Galleani fled to France, where he remained for 20 years. He spent time in Switzerland, where he collaborated in research and activism with the famous anarchist geographer Reclus. In 1887 he organized a student demonstration in honor of the Chicago Haymarket martyrs, who were executed that year. For his involvement in this Galleani was arrested and deported from Switzerland, after which he returned to France. Galleani returned to Italy, where he was found guilty of conspiracy and spent more than five years in prison and “internal exile” on the island of Pantelleria off the coast of Sicily. Escaping from Pantelleria in 1900, Galleani fled to Egypt, which then had a large Italian expatriate community and he hid among Italian anarchists there. A few months later he made it to London and then immigrated to the US in 1901.

Galleani arrived in the US at the age of 40. He initially settled in Patterson, New Jersey, then a center of Italian-American anarchism. In an article in the Barre-Montpelier Times Argus mentions how Galleani became the “defacto intellectual leader of American anarchism” in an era when anarchism was close to being a mass movement. Galleani emerged as a skilled orator with a brilliant intellect and was a fiercely anti-capitalist. An article appearing on Infogalactic quotes, a brother of a Galleanist bomb maker as saying, “You heard Galleani speak, and you were ready to shoot the first policeman you saw".

In 1902 while making a speech to striking Paterson silk workers advocating a general strike and the overthrow of capitalism, the police began firing on striking workers and Galleani was shot in the face. Indicted for inciting a riot, Galleani fled to Canada, where the border patrol then escorted him back over the US border. Galleani then settled in Barre, where he became a major figure among Italian anarchists in the city. In Barre he gave fire-breathing speeches condemning capitalism and the timidity of rival socialists.

He was a prolific writer and founded the famous anarchist weekly Cronaca Sovversiva (Subversive Chronicle) in 1903, which he published and mailed from offices in Barre for 9 of its 15 years of existence. While Galleani acted as the editor and major contributor to the paper, his name did not appear on the masthead due to the fact that he was a fugitive. Instead the well known Barre sculptor and teacher Carlo Abate was used as a figurehead. While Abate contributed his art work, there is no evidence he ever wrote for the paper. Abate himself was a visionary artist, later known for carving mainstream busts of Thomas Edison and Shirley Temple but who was known to have a strong interest in social justice.

At its height Cronaca Sovversiva had 5000 subscribers and had subscribers though out the Italian immigrant diaspora in the US ,Europe, South America and Australia. The paper had articles advocating free love, opposing organized religion and belief in God, denouncing state tyranny as well as extolling the “propaganda of the deed”, acts of violence designed to trigger a working class uprising and emphasized the importance of armed resistance to the state. The paper praised the assassination of figures such as President McKinley and King Umberto of Italy but also covered strikes and often published addresses and personal information about strike breaking business owners and others regarded as class enemies.

Several books were written expanding on Galleani’s articles in Cronaca Sovversiva including Aneliti e Singulti: Medaglioni ("Sighs and Sobs: Portraits"), which celebrated the lives of bombers and assassins as anarchist heroes. Later issues of Cronaca Sovversiva advertised a booklet, La Salute è in voi! (Health is in You!), a bomb-making manual. Cronaca Sovversiva was published from its offices on Blackwell Street in Barre, and on the annual May Day, or Primo Maggio, their masthead was changed to depict portraits of the martyrs of Haymarket. Honoring May Day was, it has been said, very likely to have been one of the few things on which the socialists and anarchists of Barre agreed.

Anarchist-socialist disputes

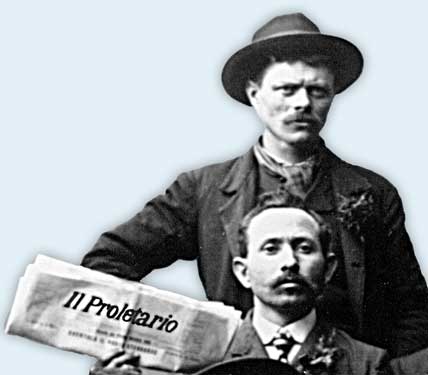

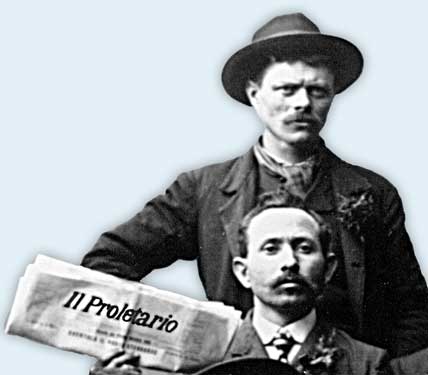

In his paper Galleani continued a long rivalry, dating back to Italy, with the socialist Giacinto Serrati, who was then editor of the popular New York City based Socialist Labor Party Italian language paper Il Proletario. A fierce polemical battle between the two anti-capitalist activists developed, with Serrati advocating a moderate approach to political activism and Galleani favoring confrontational direct action. The two began attacking each other in print.

The building of the Socialist Labor Party Hall in 1900, intended as a meeting place for unions and as a center of the radical Italian workers movement in Barre, with its hall seating hundreds was regarded as having given the socialists an unfair advantage and was regarded by Barre’s anarchists as a provocation. Tensions in Barre were further inflamed by the polemics between Galleani and Serrati in their respective papers, widely read in Barre.

In 1903 Barre socialists invited Sarrati to speak at the Labor Hall. By this time tensions between anarchist and socialists were at boiling point. Searrati was to give a talk on “Methods of Socialist Struggle”. As Serrati arrived, the Labor Hall was surrounded by angry anarchists and Serrati had to struggle though the crowd. He was scheduled to speak at 7pm but his entry was delayed. People thought his appearance had been canceled due to fears for his safety. The Labor Hall itself was packed with a hostile anarchist crowd. Anarchists began taunts about Serrati’s non-appearance. A fight broke out before Serrati could mount the podium. Shouts and taunts led to scuffles as someone pulled out a knife and someone else threw a chair. This quickly turned into a full scale brawl.

It was later claimed that anarchists had shouted, “Kill the socialists”. At one point a 39-year-old socialist, Alessandro Garetto, who had been carrying a pistol, joined the fight. He shot at least twice, one shot grazing an anarchist and the other hitting Elia Corti, regarded as Barre’s finest sculptor, in the stomach. Garetto was then thrown down the stairs of the hall and fled, running down Granite Street. Fearing he might be lynched by angry anarchists, he turned himself in to a judge who then turned him over to the police. Police Chief Brown, who had himself been attacked by anarchists a few years later, put Garetto in a wagon to be transported to the jail in nearby Montpelier.

On the way the wagon stopped to pick up an injured patient who needed emergency care at a nearby hospital. The patient turned out to be Elias Corti. Chief Brown held up a lantern so Corti could see Garetto’s face. “You are the man who shot me”, he said twice. At this point Corti’s colleague, the sculptor Samuel Novelli, who had accompanied him in the wagon, became angry and tried to throw the lantern at Garretto, but it hit the police chief instead. Novelli then tried to take the chief’s revolver. Police were able to subdue Novelli and pull him out of the wagon.

The bullet, passing though Elias Corti’s stomach, had lodged near his spine and with the medical technology of the day was impossible to remove. He died after 30 hours at the hospital and, at his request was buried the next day in Barre’s Hope Cemetery, with hundreds of people attending his funeral. Corti’s death sent shockwaves though Barre and led to a temporary truce between anarchists and socialists.

Corti was 34 years old at the time of the shooting. He had emigrated from Italy 12 years before this incident. A few years before the shooting, in 1899 Elias Corti, and his partner Samuel Novelli had been commissioned by Barre’s Scottish community to carve a statue of the beloved radical poet Robert Burns. Novelli carved the likeness of Burns while Corti did the more intricate face work. The statue is considered a masterpiece. It stands outside what was originally an elementary school and is now the Vermont Historical Society.

After his death Corti’s brother and brother-in-law carved a striking monument to him marking his grave. Corti is dressed in a dapper style in front of the tools of his trade. His hands rest on a broken column, representing a life cut short.

There is debate about what Corti was doing during the Labor Hall melee. Before his marriage he had been an active anarchist, respected in anarchist circles, and was the founder of an anarchist cell. After his marriage and as his own sculpting business took off, Corti became less politically active. According to some accounts he had agreed to attend Serrati’s talk out of a desire to keep his younger brother and two brothers-in-law out of trouble. Witnesses said that he had waved his hands, appealing for calm when the fighting broke out.

Vilification between Galleani and Serrati continued for the next several years. In 1906 Il Proletario divulged Galtieri’s name and whereabouts, blowing his cover, although Serrati later claimed this had been an accident. New Jersey officials had an extradition request for Galleani for his alleged role in inciting a riot during the Patterson strike of 1902.

Shortly after his identity had been revealed the Washington County sheriff arrested Galleani, who calmly surrendered at his home. Galleani said good bye to his wife and children and spent that night in the local jail. The next day several hundreds of his supporters arrived at the train depot in Montpelier to show their support. The day after that hundreds of people again protested in Barre’s Depot Square against Galleani’s extradition. Despite mounting protests, Vermont Governor Proctor signed an extradition order for Galleani to be sent to New Jersey. To the surprise of many however, Galeanni’s trial led to a hung jury and Galleani was released and returned to Barre.

On his return to Barre, Emma Goldman, on her second visit to the town herself, welcomed Galleani back and they jointly spoke at the Barre Opera House, to a standing room only audience of more than 900, with Goldman speaking in English and Galleani in Italian.

In 1905 there was a suspicious fire at the Blackwell Street offices of Cronaca Sovversiva, although the printing presses weren’t effected and the paper was able to continue publication. There were suspicions that the US government had been involved although nothing was ever proven.

In 1912, Galleani, due to conflicts within the Barre anarchist community, moved Cronaca Sovversiva to Lynn, Massachusetts, outside of Boston. During World War I, Cronaca Sovversiva took a strong anti-war stance, opposing US entry into the war. Galleani advised his followers in the US not to register for the draft and to move to Mexico to avoid it.

Identified as a “resident alien” who advocated the violent overthrow of the US government and who wrote a bomb making manual, the US government deported Galleani and eight of his followers to Italy in June 1919, as part of a wave of deportations of foreign-born US radicals. As a counter-attack against this Galleani’s followers began a bombing campaign against people and institutions regarded as pillars of capitalism in and around NYC including the house of John D. Rockefeller, the Tombs NYC prison police court and St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The 1920 Wall Street bombing, which killed 30 people, was believed to have been carried out by Galleani. This in turn led to the repressive Palmer Raids, a crackdown against leftists, native and foreign born alike, in which over 10,000 people were arrested and many deported.

Cronaca Sovversiva was briefly re-established in Italy after Galleani had been deported. After Mussolini came to power in 1922 Galleani was arrested and was again exiled to the island of Pantelleria. He died in 1931. The fascist government had him buried at night to prevent a rally by his followers.

Galleani’s socialist rival, Giacinto Serrati also returned to Italy and played a prominent role as a leader of the left wing of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and edited its paper, Avanti. He later joined the Italian Communist Party (PCI) but broke with them over the Comintern’s demand to break with the left wing of the PSI.

Despite the incendiary polemics of Galleani and the fighting and shooting at the Labor Hall, Barre’s anarchists were known to be peaceful and were regarded as good citizens. A local newspaper, the Barre Daily Times said local anarchists were “good citizens in that they were peaceable, honest men who mind their affairs, pay their bills, and have no desire to trouble anyone, and whose children are among the brightest scholars in our public schools”. Barre’s anarchists were not involved in Barre’s electoral politics and did not appear to have influenced the mainstream union movement to any large degree.

Socialist Labor Party Hall

The socialist movement in Barre took on a less confrontational and more peaceful approach. The first organized nationally based socialist organization in Barre was the Socialist Labor Party. It appears that it was centered in the radical Quarry Workers International Union of North America. This union, working with other groups, organized Barre’s Italian community in building the Socialist Labor Party Hall in 1900 at 46 Granite Street, a block off Barre’s Main Street and then known as a rough area surrounded by granite sheds and tenements. The Labor Hall was built for $7000.

It was in use from 1900 to 1935 as a meeting and function hall, and organizing and social space. Meetings of the SLP and the Socialist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and granite workers unions were held there as well as boxing and wrestling matches, fundraising events for strikes and worker’s relief, centers for local union organizing drives in stores and bakeries, and parties and celebrations. Worker’s insurance societies were headquartered there. State conventions for the Vermont Socialist Party were held there and despite the tensions between socialists and anarchists, Barre’s anarchists used the hall as well. The hall also had a speakeasy used during Prohibition. Primo Maggio, or May Day celebrations in honor of the Haymarket Martyrs were held at the Hall and were a combination of festive and serious.

There was some conflict before the Hall officially opened. The Granite Cutters National Union (GCNU) had agreed to rent the hall but had backed out two weeks before the scheduled opening because of an accusation that the building had been built with scab or at least non-union labor. The contractor hired to build the hall strongly denied the charge of hiring scabs and after an investigation the GCNU moved into the hall, which was opened November 28, 1900, amid a big celebration.

On the opening day Camilo Cianfaro, then editor of Il Proletario, gave a lecture on “What Is Socialism” to a standing room only audience of about 700. This was followed by dancing until early the next morning. Nine days after the opening the emblem of the hall, containing the SLP’s arm and hammer symbol, was completed by the sculptor Egidio Dunghi and was ready to be installed on the hall’s front door, where it still is today.

Prominent figures in US socialist, labor and anti-capitalist movements spoke at the Hall. IWW leader “Big” Bill Haywood spoke there in 1909 and Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs appeared during his presidential campaigns of 1904, 1908 and 1912. Arturo Giovannitti, an IWW leader involved in the famous Lowell Bread and Roses Strike of 1912 attended events at the Labor Hall. In 1914 IWW organizer Mary Harris, commonly known as Mother Jones, came to Barre in the midst of severe snowstorms to speak in support of a strike by Barre’s retail sales workers. In 1934 the fiery communist Anne Burlack, known as the “Red Flame” for her dramatic speeches, spoke at the Hall. The Barre Daily Times described her speech as advising workers to avoid strike arbitration, which she regarded a means of seducing workers from their struggle, and to mistrust small groups of labor leaders.

In 1901 a co-operative store was opened in the basement of the Labor Hall which sold Italian groceries and dry goods. Sometime later the store opened a bakery and bought a bottling plant. The store issued its own currency with the SLP arm and hammer logo. After a severe flood in 1913 and in answer to increased demand, the co-op built a second bakery behind the hall. The co-op also opened a laundry and a branch store in nearby Northfield. Some of the profits from these businesses were used to subsidize membership for who otherwise couldn’t afford co-op membership, help for people in difficulty, funds for Italian earthquake relief and support for an Italian-American mutual aid society, the Società di Mutuo Soccorso, which provided help for families devastated by silicosis.

During the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike in Lowell, Massachusetts, Barre’s radicals expressed strong solidarity with striking workers. After mill owners in Lowell announced a massive pay cut in mid-January, a wildcat strike erupted with up to 10,000 workers leaving the mills, News of this quickly reached Barre.

At a mass meeting in the Labor Hall 350 people unanimously voted in favor of a resolution supporting the Lowell strike. After a month of threats from the mill owners, escalating tension and the death of one worker, Anna Lopozzo, Lowell strikers decided to send their children out of Lowell for safety. In this “Children’s Exodus” children were sent to sympathizing families in places throughout the Northeast, including Barre. In mid-February a parade of several hundred sympathizers met 35 Lowell children. The group then marched to the Barre town hall and back and the children were brought to the Labor Hall. The marchers were accompanied by a band made up of sympathizers from Barre, Waterbury, and Bethel. At the Labor Hall the children were examined by doctors, given new coats and ID tags, and were presented with a huge banquet, before their local host families took them home. Photos of the children were taken, made into postcards that were sent to their parents. While in Barre the children attended the local schools. By the middle of March some of the Lowell children had been sent home and the last of the 35 children were sent home by the end of the month.

The Labor Hall and its enterprises were hit hard by the flood of 1927, although it managed a recovery. The Cooperative Society, which owned the hall, was forced to sell it in 1936, during the Great Depression. For the next 60 years the Labor Hall had been used as a warehouse, used at various times to store food, coal, and for a time was used as a bottling plant.

The last commercial owner of the Hall was Vermont Pak Tomato, which filed for bankruptcy in 1994. The Labor Hall was then bought by the Barre Historical Society. With support from local unions the Hall was repaired and renovated. Unfortunately, due to a bank not honoring its promises, many boxes of papers relating to Barre history were sent to a dump before historians could look at them. The Labor Hall held a Grand Reopening celebration on September 2, 2000. The Labor Hall today is used as the headquarters of the Barre Historical Society and several local unions.

Decline

Although Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italian-American anarchists whose trial continued for murder throughout the 1920s and who were facing a death sentence, received strong support in Barre, anarchism began to fade in the town after World War I, with greater mechanization and centralization of the granite industry, and larger firms pushing out smaller firms, out of which the anarchist movement had come. The post-WWI wave of repression and the deportation of foreign radicals took a toll on both Barre’s anarchist and socialist movements.

Fierce labor battles however continued during the 1920s and 1930s. In the early 1920s Barre business owners teamed up to impose the anti-union “American Plan”, which would deny union recognition, on the pretext of fighting Bolshevism. In 1933 the governor of Vermont, in a highly controversial move, mobilized the National Guard to settle a strike. At times French-Canadian workers were brought to Barre to act as scabs.

Although this occurred somewhat after the time period covered, socialists achieved some electoral success during and after WWI when Barre had two socialist mayors, Robert Gordon and Fred Suitor. Robert Gordon was an immigrant from Scotland who came to Barre as part of the first group of Scottish stonecutters to arrive. In Barre he was heavily involved in the town’s Scottish community. Robert E. Weir’s “Solid Men in the Granite City” describes how Barre’s business elites long controlled the town’s politics though use of a “Citizens Caucus” in which Democratic and Republican politicians united to keep Barre’s socialists from the SP, SLP and the Quarry Workers International Union divided and marginalized.

Gordon first ran for mayor in 1912 but narrowly lost due to opposition from the stonecutters union, who had endorsed their own candidate. Gordon with a background in union organizing, was able to make an end run around the employers political monopoly and appeal to a broader range of voters by posing as a socialist moderate against the more radical SLP and Barre’s anarchists and was elected mayor in 1914. Gordon was a classic “sewer socialist”, he made important reforms, municipalized the city’s coal distribution, greatly improved Barre’s road building and repair and worked for the financial responsibility of Barre’s Central Power Company.

Although the socialist movement in Vermont had been largely crushed during the post-WWI repression, Greg Guma, in “The History of Class Struggle in Vermont, From Socialism to The American Plan” published on thefringe.com, described how John Lawson, another immigrant from Scotland who had arrived with his parents and who had attended socialist meetings at the Labor Hall as a teenager, rebuilt the Vermont Socialist Party after WWI, during a difficult time for the left.

Fred Suitor was a protégé of Robert Gordon and was born in Quebec in 1879. Suitor had a background in union activism and was the secretary of the Quarry Workers International Union. He was elected mayor on the Citizen’s Caucus ticket, after more leftist elements came to prominence in that party instead of the SP, and served in that role between 1929-1931. Like Gordon, Suitor improved and expanded municipal services, but his programs were hard hit by the Great Depression.

Both mayors were far from revolutionaries. In “Solid Men In the Granite City”, Robert E. Weir says that “Cheap coal, water lines, sidewalks, paved roads, playgrounds, and balanced budgets are hardly the future imagined by socialist theorists.” Weir quotes Milwaukee socialist Daniel Hoan who, in 1940, declared his own twenty-four-year mayoralty to have been a “complete fizzle”, “having socialized only a stone quarry and the city’s streetlights,” in discussing the challenges of being a socialist within a hegemonic capitalist society. Perhaps showing the importance for socialists of combining shorter term reforms with a vision of the revolutionary transformation of society and the usefulness of the Trotskyist “Transitional Program”, the reality was that Barre’s fading radicalism had moved far from its earlier Italian-American heyday.