After the 2024 European elections: Rightward shift with slight headwinds

First published at Transform! Europe.

More than 350 million people had the opportunity to cast their votes in the European elections on 6-9 June. Leftists have repeatedly emphasised that the European elections are not secondary elections — they have long been used strategically, as was the case years ago by the British party UKIP for Brexit.

Even if these elections were primarily shaped by national campaigns, other common issues were at the centre of the European elections: security in the face of wars, crises and social upheavals, immigration and climate change. None of these interconnected problems can be solved at the national level. But effective and, more importantly, tangible European solutions are hard to come by in the face of global conflicts. Where current policies fail to provide solutions, or where political action stalls, voters are driven to the right. Ultimately, elections are always a referendum on which parties are most trusted to solve pressing problems, or which parties are needed in the political system as opposition parties to counterbalance ruling policies.

What is the general situation?

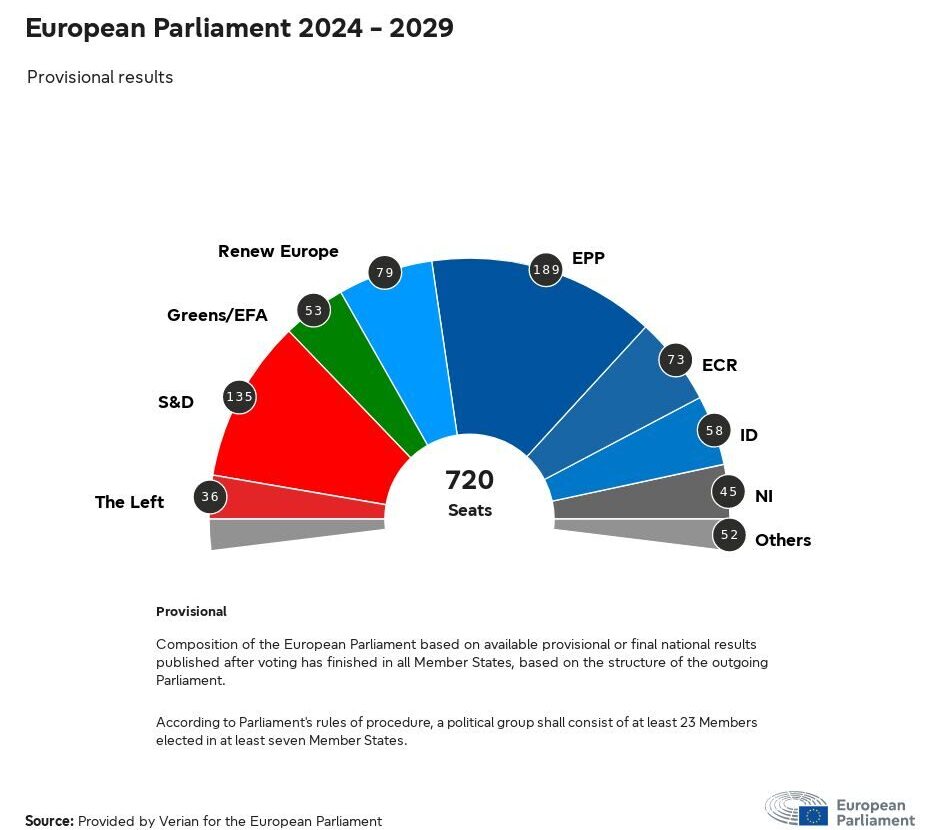

The European People’s Party (EPP) remains the largest group in the European Parliament with 186 MEPs, slightly increasing their lead. The Socialists remain at the same level as in 2019 with 135 MEPs. The Liberals have lost 23 MEPs and are now the third largest force with 79 seats. The Greens have lost 18 MEPs and, with 53 MEPs, are second to last behind the two far-right groups. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) have made slight gains and now have 73 MEPs in the European Parliament. The far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) also gained 9 seats and now has 58 MEPs in the EP. The Left Group, with 36 MEPs, is the smallest group, having lost one mandate. Behind these figures, however, there have been dramatic changes — especially within the Left Group.

Right-wing groups make gains

The right has seen an increase in support, although not as significant as anticipated, and certainly not uniformly across all regions.

In Italy, Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia emerged as the dominant party with nearly 29% of the vote. However, the broader right-wing coalition, which includes Salvini’s League (8.9%) and Forza Italia (formerly led by Berlusconi, also at 9.6%), alongside several smaller parties, commands almost half of the electorate.

In France, Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) secured the lead with 31.4% of the votes, while Macron’s Révellier l’Europe saw a decline to just under 14%. Moreover, the right-wing coalition in France, comprising RN and La France fière (Proud France), which includes the far-right figure Eric Zemmour, reached 37%. The massive losses have prompted Emmanuel Macron to dissolve the national parliament and call for new parliamentary elections just three weeks after his defeat in the European elections and the victory of the far right. This, in turn, has led to alliances forming on both the left and right, ultimately weakening the president’s camp even further. Whether this will strengthen the French right remains to be seen. At any rate, an alliance between the conservative Républicains and the extreme right-wing populist Rassemblement National (RN) seems possible.

Despite various scandals, the Freedom Party (FPÖ) remains a formidable force in Austria, securing over a quarter of the votes and positioning itself for the upcoming national elections in October. Despite controversies and exposés regarding deportation plans, the AfD has maintained its position as the second strongest party in Germany with 15.9%, particularly influential in the eastern states, which will likely impact regional elections in Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia. In Hungary, Fidesz has maintained its dominant position with over 44.3% although facing serious competition from former Fidesz member Péter Magyar and his centre-right Respect and Freedom Party (Tisza). The Polish national-conservative PiS closely is closely trailing the pro-European conservative Civic Platform (KO) with over 36%, while the Polish far-right Konfederacja gained 12%. In Bulgaria, the far-right Revival party achieved 14%.

Despite these gains, it would be inaccurate to portray the rise of the extreme right as unchecked. The situation is more nuanced. In the Netherlands, the left-green alliance led by Frans Timmermans successfully countered Geert Wilders’ rise with 21.6% of the vote, while Wilders’ PVV received only 17%. In Finland, the conservative KOK and the Finnish Left Alliance Vasemmistoliitto achieved impressive results, pushing the Finns Party below 15% to third place in the party system. Sweden also saw the Sweden Democrats fall to fourth place with less than 15%, trailing behind the Social Democrats, Conservatives, and the Environmental Party. In Spain, Vox remained below 10%, as did Chega in Portugal.

Setbacks for the Greens and status quo for the Social Democrats

For the Social Democrats/Socialists, the losses experienced by the German Social Democrats were balanced by strong performances in countries such as the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, or Sweden, as well as the resurgence of the Socialists in France and Pasok in Greece. However, in Spain, the PSOE (30%) fell behind the conservatives (34.2%). In Denmark, the Social Democrats [15.6%] trailed behind the Socialist People’s Party (SF — (17.4%). Ultimately, the Social Democrats were able to maintain their position as the second strongest force in the EP Parliament with 135 seats.

The majority of the party losses in the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance are attributable to Germany, where Bündnis 90/Die Grünen fell from 21 to just 12 seats in the European Parliament. Further losses were also recorded by the Greens in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Austria. In the east (Romania, Slovenia, Croatia), south (Italy, Spain), and north (Denmark) of Europe, however, gains were recorded. Nevertheless, the ‘green wave’ of 2019 appears to have weakened considerably, leading to concerns that the losses of the Greens and progressive forces could result in a less ambitious European climate agenda.

The Left Group without major changes

The Left Group remains largely unchanged, with results nearly identical to the previous elections with 5% of the vote and 36 seats. However, there have been notable developments within the group. In addition to the success of the Finnish Left Alliance, the Cypriot AKEL, though losing one seat, remains a significant presence with over 20% of the vote. In Sweden, the Left Party saw a notable improvement of over four percentage points to reach 11%. Similarly, La France Insoumise in France saw an increase of over 3% to nearly 10%. However, the French Communists, under the banner of Gauche Unie, remained below 3%.

In Greece, Syriza emerged as the second largest party, after the conservatives, with 14.9%, while the Communists (KKE) secured 9.25% of the vote. Mera25 and Néa Aristerá fell short of the 3% threshold with 2.54% and 2.45% respectively. Denmark’s Left Party secured 7% of the vote. In Belgium, the PTB / PdVA achieved 5.6% and 5.13% respectively in Wallonia and Flanders. Spain’s Sumar received 4.65%, and Podemos secured 3.27% of the vote — a significant decline compared to recent years. In Portugal, Bloco achieved 4.25%, and the green-communist CDU received 4.12%. Italy’s Alleanza Verdi e Sinistra secured 6.6%, while the Pace Terra Dignità party received 2%. Croatia’s Možemo achieved 5.9% and, with one MEP, is likely to align with the Greens. Slovenia’s Levica fell short of expectations with 4.75% of the vote, while Luxembourg’s De Lenk achieved 3.15%. The Austrian Communist Party (KPÖ) missed the 4% threshold, achieving 3%. DIE LINKE, at 2.7%, lost about half of its voters from 2019. The Dutch Socialists (SP) got 2.2%. Kateřina Konečná of the Czech KSČM will enter the European Parliament as part of a left-patriotic alliance. All in all: The few successes cannot hide the continued defensive posture of the left and the existential crisis of individual parties.

Shifting majorities

There is currently only one clear majority, consisting of conservatives, social democrats and weakened liberals, which accounts for more than 55% of MEPs. However, it must be borne in mind that formal majorities in the sense of a majority ‘bloc’ do not have the same binding force as as majority voting ‘blocs’ do in national parliaments. Beyond party families, very different majorities can come together. These can be centre-right majorities — which have now been enlarged — when it comes to further expanding the European border regime or limiting or phasing out climate protection programmes. Majorities for increased militarisation of the EU are possible under the leadership of conservatives, liberals, social democrats, and parts of the Greens. The issue of EU enlargement, which can be blocked by the right, is becoming a battleground in the EU. The extent to which the principles of the rule of law remain cornerstones of democracy remains to be seen.