Evolution not 'reinvention': Manning Marable's Malcolm X

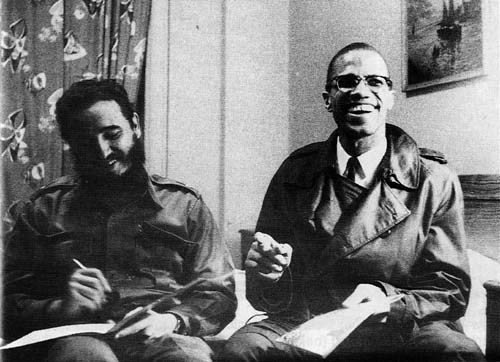

Malcolm’s political evolution was influenced by his own experiences and his discussions with Fidel Castro and Che ..., with Nasser in Egypt and Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, as well as with discussions with North American ex-patriates in Africa.

By Malik Miah

Many will ask what Harlem finds to honor in this stormy, controversial, and bold young captain — and we will smile ... .And we will answer and say unto them: Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him, or have him smile at you?... And if you know him you would know why we must honor him: Malcolm was our manhood, our living Black manhood!... And we will know him then for what he was and is — a prince — our own Black prince — our own Black shining prince — who didn’t hesitate to die, because he loved us so. — Ossie Davis’s eulogy, February 27, 1965, Faith Temple Church, New York City (p. 459)

Against the Current #154, September-October 2011, posted at Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal with permission -- Manning Marable's final book, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, is a serious political biography of one of the most historic figures of the African-American community. Marable’s interpretation of papers provided by Malcolm’s family estate, along with files from the FBI, New York City Police Department and new interviews from those who knew Malcolm and the Nation of Islam (NOI), add to our understandings and debates about Malcolm’s views and evolution.

Marable’s untimely death on April 1, 2011, unfortunately prevents him from responding to critics. Yet the well-referenced and sourced book provides a solid foundation to all those seeking to understand Malcolm and what he represents for the current generation of Black and left activists.

A lifelong activist, Marable viewed his scholarly work as a complement to his involvement in political action. Yet as a scholar his work will live on. It took more than 20 years of research to complete the book. Marable put together an invaluable legacy at Columbia University where he taught. In addition to the biography, he built a vibrant multimedia presentation at http://mxp.manningmarable.com.

Political biography

Biographies by definition are political. Each provides an author’s interpretation of the subject. Few biographies if any are simple presentations of a chronology of a person’s history and what took place in the subject’s life.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of books and articles have been written about Malcolm X. Marable’s book is an important addition to the library both because of the new documentation and Marable’s unique interpretation of that information.

The biographer’s burden, Marable wrote, is “to explain events and the perspectives and actions of others that the subject could not possibly know, that nevertheless had a direct bearing on the individual’s life“ (p. 479).

Marable explained that what led him to write the book was his own dissatisfaction with the most famous and widely read book on Malcolm, The Autobiography of Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley. Haley, a liberal Republican and subsequent author of the book Roots, according to Marable, exaggerated Malcolm’s early life and left out details of other aspects of his life. “A closer reading of the Autobiography as well as the actual details of Malcolm’s life reveals a more complicated history. Few of the reviews appreciated that it was actually a joint endeavor” between Malcolm and Haley (p. 9).

Marable argued:

From an early age Malcolm Little (as he was born) had constructed multiple masks that distanced his inner self from the outside world. Years later, whether in a Massachusetts prison cell or travelling alone across the African continent during anticolonial revolutions, he maintained the dual ability to anticipate the actions of others and to package himself to maximum effect (p. 10).

“These layers of personality”, he continued, “were even expressed as a series of different names, some of which he created, while others were bestowed upon him: Malcolm Little, Homeboy, Jack Carlton, Detroit Red, Big Red, Satan, Malachi Shabazz, El-hajj Malik El-Shabazz. No single personality ever captured him fully. In this sense, the narrative is a brilliant series of reinventions, ‘Malcolm X’ being just the best known.”

The invention of 'reinvention'

This is a constant theme in the book: Malcolm’s conscious reinvention of himself to serve his immediate objectives. It is a strange methodology. Malcolm, like most people, was impacted by personal and broader objective circumstance not in his control. Malcolm’s political evolution is real, as Marable describes throughout the biography. To imply that it was a conscious act of “invention” weakens his valid points.

Malcolm’s political-religious-ideological outlook did evolve over the years. His own experiences in life and as a leader of the Nation of Islam (NOI), and in his final year of life seeking to build two new organisations, reflect that ceaseless political-social-ideological evolution that Marable discusses in his work. Malcolm’s story, thus, is powerful enough with no “invention”. Why Marable focused so much on his storyline of “reinvention” can only be surmised.

Haley and the publisher clearly structured the Autobiography to sell more books. This helps explains why 40% is about Malcolm’s early years growing up in Michigan and then as a petty criminal in Boston and New York.

However, his 12 most important years occurred after he joined the NOI and in his final year, when he became more aware of orthodox Islam and the anti-colonial democratic revolutions in Africa and Asia. His internationalism came through in his final two trips to Africa and the Middle East, including the hajj to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It was also reflected in his support for the Cuban Revolution and decision to take the issue of racism and human rights to the United Nations.

It is important to recognise that Malcolm’s final year was extremely busy. He took two trips abroad and launched two new organisations. He also responded to constant threats to himself and his family from the Nation of Islam, which now called him an “enemy and traitor”. The week before his assassination, his home was firebombed by unknown assailants. It is hard to believe that he had much time to seriously go over the final drafts of Haley’s chapters.

I don’t agree with the term “reinvention” since it implies that Malcolm consciously manipulated his own history for predetermined motives. In reality, Malcolm evolved in his outlook. Nevertheless, what Marable creates in his biography is an advance over most other books on Malcolm that I have read. The reader is able to separate the facts and story from Marable’s own interpretation and opinions. The best way to know Malcolm is to listen to and study his recorded and published speeches.

Evolution not reinvention

The book is about both Malcolm’s evolution or “reinvention” as Marable calls it, and Marable’s own political evolution over 30 years of activism and political writing.

His collection of articles published in 1995, Beyond Black and White, which Marable updated in 2009, summarised his outlook, which I outlined in a review written for the Australian magazine Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal:

Marable, remaining true to his long-time radicalism, argues for building a ‘new, antiracist’ leadership. A new antiracist leadership, he states, ‘must be constructed to the left of the Obama government that draws upon representatives of the most oppressed and marginalized social groups within our communities: former prisoners, women activists in community-based, civic organizations, youth groups, from homeless coalitions, and the like. Change must occur not from the top down, as some Obama proponents would have it, but from the bottom up (http://links.org.au/node/1660).

This provides an important framework for understanding how Marable saw Malcolm X. Much of what Marable called Malcolm’s “flaws" and “mistakes” were tied to his own political views to build a multi-racial movement today.

The real test of any leader is: did he or she live up to and stand on their stated principles? In Malcolm’s case, these principles centred on anti-racism and self-determination. I believe a serious reading of Malcolm X’s words shows that even as he evolved from a strict follower of the ideology of the Nation of Islam’s Elijah Muhammad, he maintained his fulcrum as a militant Black nationalist (from Marcus Garvey to Elijah Muhammad) and as a Pan-Africanist and ultimately an internationalist.

Many of Marable’s political points about what Malcolm would say today about Barack Obama and Black self-determination reflect his own views and those of Malcolm. For example, Marable interjects his assumptions about what Malcolm would likely say if he lived today:

Given the election of Barack Obama, it now raises the question of whether Blacks have a separate political destiny from their white fellow citizens. If legal segregation was permanently in America’s past, Malcolm’s views today would have to radically redefine self-determination and the meaning of Black power in a political environment that appeared to many to be "post-racial" (pp. 485-486).

I found this a strange observation, since we know that racism is institutional and structural. The fact in 2011 is that even with the first African-American president, the conditions for the Black poor have worsened with the Great Recession beginning in 2008. The rise of the Black middle and upper class even to a position of the highest political office hasn’t resolved racial discrimination. Divisions between rich and poor are sharper than ever.

Marable himself called for a new anti-racist leadership in previous works to take on these ongoing issues facing the Black community. Why would Malcolm, if he lived, “radically redefine self-determination and the meaning of Black power” unless he agreed that we are living in a “post-racial society”? Few actually believe that’s the case with the rise of the so-called Tea Party movement that appeals to bigotry as one of its calling cards.

The strength of this biography, however, is not Marable’s interpretation and political observations. It is his providing more details and proof about Malcolm’s political trajectory while still a minister in the National of Islam, and his all-important final year after his suspension and de facto expulsion from the NOI when he moved clearly in a more revolutionary and internationalist direction. Nine key points of Malcolm’s evolution and transformation are discussed by Marable:

1. Malcolm’s political evolution away from the NOI philosophy of non-participation in politics. It began in the late 1950s as he became the main recruiter to the NOI. In many ways, Malcolm was reconnecting to his Garvey roots.

2. His move toward orthodox Islam begins with his 1959 trip to the Middle East. This began his journey to reconsider the NOI’s unique views on Islam, including Elijah Muhammad’s self-designation as “Messenger from Allah” and that all whites are "devils".

3. His changing view of the traditional civil rights leadership, including its strategy of litigation and non-violence to achieve full citizen rights and integration. Malcolm, even as a leader of the NOI, began to move toward a strategy of the “Black united front”. This was formalised in 1964 when he set up the secular Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU).

4. Malcolm’s decision to establish two new organisations — one Islamic, the Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI) and the other secular, the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). The OAAU was modelled on the newly formed Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Africa. These two decisions reflect his far reaching political thinking. It shows Malcolm was way ahead of his supporters who still held most of their NOI views. Malcolm combined Black nationalism, orthodox Islam, Pan-Africanism and internationalism in his new vision.

His approach, as noted by Marable, was a “dual-track strategy”, building a secular group and an orthodox Muslim organisation. The program of the OAAU was to reach out to all those in the Black freedom movement and to link up with the anti-colonial revolutions and newly independent African and Middle Eastern countries. (See page 341 on formation of OAAU. Its founding program became a model for future Black Power organisations including Black nationalist formations with militant agendas such as the Black Panther Party, the National Black Independent Political Party and Black United Front.)

5. New sources and insights on Malcolm’s assassination and who was behind it. Marable provides strong circumstantial but believable evidence from interviews, oral histories and available government records that five people connected to the Newark, New Jersey, Nation of Islam Mosque were sent to assassinate Malcolm. Four got away but two of the men convicted were innocent. He shows that the cops, particularly the New York Bureau of Special Services (BOSS), were complicit by their inaction. Many of those records, especially the identity of informants, remain sealed.

6. Malcolm’s decision to speak at Militant Labor Forums, sponsored by The Militant newspaper and the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), reflect a transformation that clearly was not a “reinvention” as defined by Marable. The SWP was a small Trotskyist formation and predominantly white. The Communist Party, active in Harlem, was larger but highly critical of the NOI and had denounced Malcolm as a “Black racist and Black supremacist".

Of the old left formations at the time, only the SWP strongly supported Black nationalism and its revolutionary dynamics for the working class as a whole. Malcolm clearly knew what the SWP was. His travels abroad, meeting with anti-colonial revolutionaries and his support for the Cuban Revolution opened the door to collaboration with US socialists. His new views included all who would fight oppression, including socialists, as potential allies of the Black freedom movement. (See pp. 335, 336, 377, 389, and 405-406.)

7. Malcolm’s views on women, while standard at the time, were also being reconsidered prior to his assassination. His travels abroad impacted his views on the role of women in the freedom struggle. Some of what Marable wrote is controversial because there is a tendency to be ahistorical. The NOI’s attitude toward women and their role in the broad social movements was not much different than other groups, including radical organisations. It took the rise of the women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s and 1970s to begin to change to those relationships.

8. The role of the government, FBI, CIA and police and their use of informants and other surveillance tools against potential Black leaders was known. It was not widely understood until the release of the FBI COINTELPRO files in the 1970s.

9. While Marable deals extensively with internal divisions in the NOI, Muhammad’s immorality (sleeping with his NOI secretaries) and jealousies, the above points (1-8) are the most important. Malcolm’s “reinvention” as a dissident was not by design. He did not consciously compete with other NOI officials to become the next leader of the NOI.

Malcolm was in fact slow to see the maneuvres against him as Marable shows. He was forced out (“suspended” and effectively expelled) by Elijah Muhammad. It was not in response to an organised factional fight. Some criticisms of Malcolm’s mode of functioning (charges of enacting harsh discipline) reflect how the NOI was organised. The NOI functioned, in many ways, as a disciplined centralised group (for example, the newspaper campaigns and mandatory requirements to sell Muhammad Speaks.)

Roots in Garvey

Malcolm’s evolution starts with his parents who were active in Marcus Garvey's nationalist movement in the 1930s. Garvey came to the United States from Jamaica in 1916 and built the largest mass urban-based Black movement in the history of the country. Unlike the NAACP, which focused on legal means to improve the state of Blacks, Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) appealed to an early brand of Black nationalism (never using the term) that targeted the rising middle class, working poor and rural workers. He also embraced Black capitalism.

In contrast to Booker T. Washington’s strategy of accommodation within the system, Garvey promoted “Back to Africa” because he could not see a future for African Americans in a racist country. In fact, Washington also believed segregation and Jim Crow were permanent and unlikely to be overturned. (Marxists for the most part also thought Jim Crow would only end with a successful socialist revolution.)

Marable shows there is a strong continuity from Garvey to Malcolm X. Many of the new recruits to the Nation of Islam were old Garveyites or influenced by the NOI’s religious-based Black nationalism.

For the young Malcolm, as it was for all Blacks in that period, the number one issue was economic survival. What Malcolm Little did to survive was no different than what tens of thousands of other urban Blacks did — hustle.

When Malcolm was sent to prison for burglary convictions, his eventual recruitment by his family to the ideology of the NOI was not a surprise. His brothers and sisters told him it was similar to the Garvey ideas that his parents practiced.

This part of the story is detailed in the Autobiography and many other books on Malcolm X. The point for Marable is to correct the Autobiography’s errors and show that Malcolm repeatedly reinvented himself.

Political action

The NOI had modest growth in the 1950s even though there was a growing civil rights campaign for full equality. The NOI’s apolitical stance (not its unique religion) isolated it from many in the Black community.

Harlem, where Malcolm became head minister, was a centre of Black agitation. To recruit to the NOI, he bent the NOI policy on political non-participation. Although he did not instruct members to register to vote, he got the local mosque to stand up to the police and reach out to others in the community. As Marable notes, “Elijah Muhammad’s resistance to involvement in political issues affecting Blacks, and his opposition to NOI members registering to vote and becoming civically engaged, would have struck most Harlemites as self-defeating” (p. 109).

Malcolm continued recruiting based on the NOI ideology that separation by Blacks was the only solution to racism and white supremacy. Yet he told his members never to turn the other cheek in the face of violence or discrimination from whites. Marable correctly points to this contradiction and conflict between the NOI Chicago headquarters apolitical preaching and Malcolm’s actions. The seeds were already planted for future conflicts.

Government role

The other strong sections of the book concern the government. The growing militancy of the Black community in general, after the desegregation ruling by the US Supreme Court in 1954 and the rise of anti-colonial revolutions in Asia and Africa, was a factor in the surveillance programs run by the cops and FBI. While Marable spends a lot of time on the machinations between the Chicago NOI leadership and its fear of Malcolm because of his leadership abilities, the government saw Malcolm as its number one NOI target. He had the potential to galvanise urban Blacks. The FBI worried that the NOI under Malcolm could join forces with the rising civil rights campaigns led by Martin Luther King and the civil rights leadership council.

While King preached non-violence as a tactic, there was a younger generation becoming fed up with that approach. They were represented by SNCC leaders and others advocating the right of self-defence (e.g. Robert Williams in North Carolina) in the face of white violence. In the eyes of the FBI, the NOI’s Black separatist and anti-white supremacist ideology, even with its policy of refusing to take political actions, made it more of a serious threat to the government than the SCLC’s and NAACP’s legal push for full citizenship.

Malcolm X was careful not to be entrapped by the FBI even as he openly endorsed the right of self-defence. We still do not know what role the FBI and New York police played in the events of February 21, 1965. What is known — and Marable describes the events very well — is what the cops did do on the day of Malcolm’s assassination: absolutely nothing.

The CIA had spied on Malcolm in Africa and the Middle East. They placed cops outside all of his events in Harlem and elsewhere. Yet when five assassins came to the Audubon Ballroom to kill Malcolm, the police were blocks away. They couldn’t even find an ambulance to take him to the nearby hospital. To this day, “both the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the New York Police Department continued to suppress thousands of pages of surveillance and wiretapping related to Malcolm”. The suppressed information probably shows who the informants were and what happened to those involved in the assassination who escaped (p. 490).

What is known for sure is that two of the NOI members convicted for the assassination were not there: Norman Butler and Thomas Johnson. Only Tallmadge Hayer, who was caught at the scene, was part of the assassination team.

In the late 1970s Hayer (also known as Thomas Hagan) issued an affidavit clearing Butler and Johnson. But no action was taken. All three men are now on parole. Marable says Willie X (William Bradley of Newark) fired the fatal shotgun blast and still lives in New Jersey.

Because the FBI and New York cops refused to seriously investigate the assassination and open all their files, the answers to the questions — Who issued the kill order in the NOI hierarchy? What role did the government play? — remain unknown. An independent investigation is needed, not a whitewash by the FBI or New York cops.

The publication of Marable’s book has added to new public pressure to reopen the case. The July 23, 2011, issue of the New York Times reports that Ilyasah Shabazz, one of Malcolm’s six daughters, is supporting the call to reopen the case. In addition, reports Shaila Dewan, the call comes from “the nation’s most persistent advocate of civil rights-era justice, Alvin Sykes of Kansas City, Missouri. Mr. Sykes was instrumental in the reopening of the investigation into the killing of Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955 and in persuading Congress to allocate millions of dollars to the investigation of civil rights “cold cases.”

What we do know from the revelations of the FBI COINTELPRO files is that the FBI and CIA considered Malcolm and King as threats who must be neutralised. Both leaders were assassinated in their prime.

Malcolm and women

Another sub-theme is Marable’s treatment of Malcolm’s supposed sexual views and activities — in his youth, in the NOI and how he treated his wife Betty. Much of this is not very interesting since it had little relevance to Malcolm’s political-religious and ideological evolution. Whether he had homosexual inclinations or encounters, and his relations with his wife and other women, simply give the reader some insight into his personal issues.

It is true that women in civil rights groups and religious formations were expected to follow the male leaders. Like others in the Black freedom movement, Malcolm did not value the leadership role of women. Black women activists complained about their second class roles. It took the rise of the feminist movement to begin to change these relationships and allow issues of sexism to be taken up along with racism.

Malcolm’s leadership functions in the NOI were not the same as Elijah Muhammad’s, who used his status as the “Messenger” to have sex with young women followers. The “Messenger’s” hypocritical morality did impact Malcolm’s decision to leave. But, the primary reasons for his break were political differences and the NOI’s internal corruption.

Marable also calls the NOI a “cult”, implying that Malcolm’s independence was another reason why Elijah Muhammad and his cronies turned against him. It really had little to do with the NOI being led by a cult figure or not. An objective reading of his evolution shows that Malcolm’s focus was building the broader political movement and organising the faithful to world Islam. Malcolm was declared an “enemy and traitor” to justify attacks. What threatened the NOI leadership most was Malcolm’s authority among NOI members. Malcolm's Muslim Mosque, which had already received official recognition from the world Islamic community, could pose a future challenge.

The NOI leaders were less fearful of the OAAU since it was secular and supported political activity.

I assume the sections on Malcolm’s alleged sexuality or inclinations were to show how Malcolm was human, with flaws, and sought to manipulate his own biography — fitting the “reinvention” premise.

OAAU’s significance

Malcolm spent nearly half of 1964 abroad in two trips where his political evolution from a narrow nationalist to an internationalist occurred. Although the OAAU had a short existence, I consider its program and objectives one of the most significant accomplishments of Malcolm’s final year.

The goal of building a broad Black united front while seeing African Americans as a vanguard minority, as an integral part of the world’s majority people of colour, a leading force that could change the country, was truly a revolutionary vision. Malcolm’s decision to transform the fight against racism to a human rights issue that should go before the United Nations won wide support. This was not an early attempt to advocate a “colourblind” policy and a move away from Black nationalism as some have argued; it was an astute tactic to place the Black fight for self-determination on the world stage.

At the same time, Malcolm’s view that the religion of Islam is colourblind and that all races should become Muslims was a rejection of the NOI’s “white people are devils” ideology. It was his way of telling African Americans to have faith in Islam and have Black pride and independence from white supremacy. He was not turning away from his firm belief that Black unity and solidarity were essential to winning freedom. Malcolm firmly believed that the US constitutional system was bankrupt for African Americans.

Marable surprisingly missed that deeper meaning of Malcolm’s decision to create these two organisations in 1964. In fact, like many others who have written about Malcolm’s evolution, Marable saw Malcolm either moving toward a King-type of position on issues of civil rights or toward the Marxist class view of race. Neither was the case.

Marable wrote, “At the end of his life he realized that Blacks indeed could achieve representation and even power under America’s constitutional system. But he always thought first and foremost about Blacks’ interests” (pp. 482-3). I know of no speech or interview by Malcolm stating that he thought it was possible Blacks could “achieve representation and even power under America’s constitutional system”.

There is no contradiction to being for Black self-determination and human rights, or for a Black united front and a coalition with all those rising up for equality and against racism. Malcolm’s more complex reasoning was learned from his own experiences and his discussions with Fidel Castro and Che in Cuba, with Nasser in Egypt and Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, as well as with discussions with North American ex-patriates in Africa. Malcolm openly praised the Non Aligned Movement as an example for Blacks. He also hailed the Chinese revolution.

Marable’s positive treatment of the Socialist Workers Party was not expected by this reviewer, in view of his recent politics. Marable in recent years had become more critical of the SWP’s support of Malcolm X and saw it as serving its own purposes. That was never the case; the SWP was the only Marxist party at the time that supported Black nationalism and its revolutionary dynamics. The SWP saw no contradiction to full support of the mass civil rights movement for full equality and the rise of Black nationalism.

I first met Manning in the early 1970s when I was a leader in the Young Socialist Alliance and the SWP. He had read The Militant newspaper and other Trotskyist literature, including George Breitman's books on Malcolm X. At that time, Marable saw no contradiction between militant Black nationalism and the socialist world view.

In 1964, OAAU representatives spoke at Militant Labor Forums sponsored by The Militant newspaper of the SWP. Malcolm was interviewed by leaders of the Young Socialist Alliance and was introduced at a rally at the Audubon Ballroom by Clifton Deberry, the SWP’s 1964 presidential candidate, after his final trip to Africa (pp. 389, 406). I believe Malcolm did this to make a broader point: that African Americans needed to work with all races and groups supporting Black freedom.

Malcolm attacked the two-party system and supported self-organisation, but never advocated building a Black third party, even though the Freedom Now party was formed in Michigan and ran candidates for office in 1964.

Malcolm’s political evolution to seeing class exploitation and capitalism as a system tied to racial oppression was part of an evolving political outlook. His willingness to be associated with the SWP and other socialists showed his reappraisal of alliances with progressive organisations.

The SWP was a strong supporter of revolutionary Black nationalism. Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky first explained in the 1930s why Black people would serve as the vanguard of a working-class revolution. The SWP adopted his outlook and the theory of combined tasks for the US revolution — national self-determination for the oppressed and working-class power.

Positive message for new generations

Marable has been criticised for leaving out many important political developments in the Black movement since 1965. I don’t consider those valid criticisms.

His overall presentation will get new readers to go back and re-read the Autobiography of Malcolm X and more importantly the speeches of Malcolm X. It will lead a new generation to read or listen to “Message to the grassroots” and his “Ballot or the bullet” speeches, which indicate some of his more far-reaching radical views on Black unity and self-defence.

Critical thinking is key to building a new militant leadership in the Black community and Marable’s book will help advance that process. Whether or not one agrees with Marable’s conclusions or views about the “reinvention”, there is no doubt Marable considered Malcolm X a historic leader of the African-American people.

“And finally”, Marable concludes,” I am deeply grateful to the real Malcolm X, the man behind the myth, who courageously challenged and transformed himself, seeking to achieve a vision of a world without racism” (p. 493).

[Malik Miah is an editor of the US socialist organisation Solidarity's magazine Against The Current. He is a long-time activist in trade unions and a campaigner for Black rights.]

Evolution not 'reinvention': Manning Marable's Malcolm X

Malcolm never met Fidel and Che in Cuba. He never visited the island nation. On Fidel, see: http://panafricannews.blogspot.com/2006/12/historic-meeting-of-presiden… It questionable whether he met Che although Abdul Rahman Muhammad "Babu", the Zanzibari revolutionary, a friend of both men, brought a message from Che, who was in NYC, to a 1964 meeting at the Audobon Ballroom.

i was surpized to read that

i was surpized to read that trotsky had stated in the 30's that black folks had the dual task of leading their national struggle and leading the u.s. multi-national working class struggle. also helps explain swp's consistant role in support of mumia.

however the ass kicker is that they seem to be the only trot formation to uphold this line, in fact in my experience, trots suck on the national question on this turtle island. do the rest(ie 4th international, sparticus, radical women, etc.) of the trotskyite trend kno about such statements?

maybe there is a need to share the sources?

as a malcolmite, i'd heard that marabelles book suckt, so i never bothered to read/buy it. this is the most balanced review that i've seen yet, altho i don't kno whether i'll buy it or not. i'd like to remind folks of a saying of malcolms, " u r either a part of the problem or a part of the solution", take yo pick.

Malcolm X

Malcolm was moving to the Left in the last year of his life. As stated by others, he was much influenced by his travels in North, East and West Africa, where he met not only the new independent countries' leaders, but also other political activists. But on his visit to France and visits to England, he met more left-wing activists, some of African origins/descent, others Whites. Please read my 'Malcolm X: visits abroad', to learn much more than what is in Marable's book. Marika Sherwood