Empire through submission (Part I): Characterising Trump’s foreign policy

First published in Spanish at CEDES. Translation by LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

Global hegemony in the interstate system refers to the capacity of a leading state to exercise leadership and governance within the anarchy of supposedly sovereign states, which are constantly seeking wealth, power, prestige or security. Giovanni Arrighi aptly noted that global hegemony is not the same as pure and simple domination, as the hegemonic state must be capable of steering the interstate system toward a kind of general interest, at least that of the owning classes and those in power.1 The capitalist world-economy is not a global empire; therefore, becoming its hegemonic power has always required a certain mix of coercion and consent. Coercion alone is not enough to dominate the world. The United States’ historical global hegemony over the modern world-system is no exception. However, given the rugged path embarked upon by the Trump 2.0 administration, it seems increasingly evident that US hegemonic power, in its crisis-dispute phase, is seeking to counter its loss of relative power in the field of consensus by doubling down on coercion, “mafia-style blackmail”, exploitative domination and the pursuit of submission.

The question then arises: what has changed in the US’s Grand Strategy under Trumpism, particularly during his second administration? The purpose of this essay is to explore this question in three parts. Part I will delve into homegrown traditions that shape the matrix of US foreign policy, to argue that Trumpism amalgamates reactionary forces within the interstate system. A forthcoming Part II will address the political economy of Trumpian neomercantilism and, concurrently, explore the hypothesis of a McCarthyist foreign policy toward Latin America. Finally, Part III will examine new imperialism, exploitative domination, and empire through submission as responses to the current hegemonic conflict in the capitalist world-economy, in light of Trump's foreign policy toward Latin America during his second administration.

1. Trump 2.0: A Hamiltonian Jacksonianism?

How should we characterise Trump’s second term administration’s foreign policy? To answer this question, we need to turn, prima facie, to the typology developed by Walter Russell Mead in Special Providence. There, the author sets out to strip US foreign policy of the interpretive framework of European realpolitik, most associated with Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski, in favour of looking at more homegrown traditions.2 To Kissinger’s typology, composed of Wilsonian idealism and Rooseveltian realism, Mead counterposes four types. In the words of Perry Anderson, Mead believes:

the policies determining these ends were the product of a unique democratic synthesis: Hamiltonian pursuit of commercial advantage for American enterprise abroad; Wilsonian duty to extend the values of liberty across the world; Jeffersonian concern to preserve the virtues of the republic from foreign temptations; and Jacksonian valour in any challenge to the honour or security of the country.3

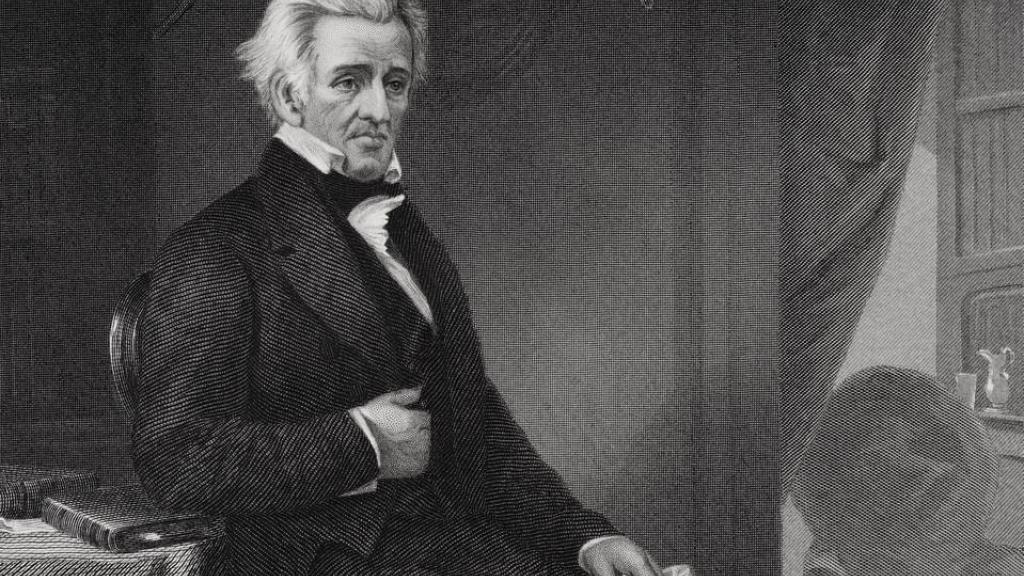

Characterising the first Trump administration (2017–21), Mead wrote in early 2017 that Trumpism represented a Jacksonian rebellion against the standard pillars of US foreign policy since World War II.4 According to Mead, Obama had been the president with the greatest contempt for the Jacksonian legacy, while Trump was its revenant.5 But what is the Jacksonian tradition? And, more importantly, to what extent can we take seriously the capacity of the Jacksonian tradition to shape the second Trump administration’s foreign policy? After reviewing, in comparative terms, the extensive history of the US’s capacity to kill people abroad, Mead writes in Special Providence:

Nevertheless, the American war record should make us think. An observer who thought of American foreign policy only in terms of the commercial realism of the Hamiltonians, the crusading moralism of Wilsonian transcendentalists and the supple pacifism of the principled but slippery Jeffersonians would be at a loss to account for American ruthlessness at war. One might well look at the American military record and ask William Blake’s question in “The Tyger”: “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”.6

That other tradition, distinct from Hamiltonian profit-driven calculation, Wilsonian democratic idealism or Jeffersonian republican nationalism, is Jacksonian. The so-called “Jacksonian society” described by Mead offers a wealth of elements for developing a phenomenology of Trumpism. However, given the objectives of this text, it is necessary to focus on two fundamental tenets of Jacksonianism: honour and violence. Let us quote Mead at length on this point:

… while Jeffersonians espouse a minimalist realism under which the United States seeks to define its interests as narrowly as possible and to defend those interests with an absolute minimum of force, Jacksonians approach foreign policy in a very different spirit, one in which honor, concern for reputation, and faith in military institutions play a much greater role… Unlike Wilsonians, who hope ultimately to convert the Hobbesian world of international relations into a Lockean political community, Jacksonians believe that it is natural and inevitable that national politics and national life will work on different principles from those that prevail in international affairs. For Jacksonians the world community Wilsonians want to build is a moral impossibility, even a moral monstrosity… Given the moral gap between the folk community and the rest of the world, and given that the world’s other countries are believed to have patriotic and communal feelings of their own — feelings that similarly change once the boundary of the folk community is reached — Jacksonians believe that international life is and will remain both violent and anarchic. The United States must be vigilant, strongly armed. Our diplomacy must be cunning, forceful, and no more scrupulous than any other country’s. At times we must fight preemptive wars. There is absolutely nothing wrong with subverting foreign governments or assassinating foreign leaders whose bad intentions are clear. Indeed, Jacksonians are more likely to tax political leaders with a failure to employ vigorous measures than to worry about the niceties of international law. Of all the major currents in American society, Jacksonians have the least regard for international law and international practice.7

Let us momentarily set aside our comments on Mead’s words to allow us to develop our argument. Writing in August 2024, when the Jacksonian rebellion had lost steam, Mead rediscovered Slavoj Žižek’s maxim that “the true ‘permanent revolution’ is already capitalism itself.”8 Expressed in terms of the declining hegemonic power’s foreign policy, Žižek’s maxim translates into Anderson’s dictum that “In substance, [US foreign policy] has been unswervingly Hamiltonian.”9 In Mead’s view:

Although Jacksonian national populism and Jeffersonian isolationism have their legitimate place in American foreign policy debates, neither can fully address today’s challenges. Another historical school of U.S. foreign policy, Hamiltonian pragmatism, is better suited to the crises of the contemporary world… The driving force behind the Hamiltonian renewal is the rising importance of the interdependence of corporate success and state power… Both business and government leaders are today discovering something that Hamilton could have told them has long been true: economic policy is strategy, and vice versa.10

China’s manufacturing and geopolitical rise has led US geostrategist elites to rediscover the ultimate foundations of wealth and power in the capitalist world-economy and the modern interstate system. It was Alexander Hamilton himself who, in 1791, succinctly stated this truth when he asserted: “Not only the wealth; but the independence and security of a Country, appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures. Every nation, with a view to those great objects, ought to endeavour to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply.” Trump’s Jacksonian rhetoric, as well as certain Jeffersonian gestures aimed at the masses, are a mask that obeys a master, namely, capital. Nevertheless, form and content are dialectically mediated, co-determining and distorting each other. MAGA’s accusations against the empire acting as the “world cop” under the neoconservatives of the Bush Jr. administration can easily be transmuted into the empire as a “benevolent assassin” in the Caribbean, according to Jacksonian doctrinal guidance. Ultimately, if we turn to Walter Benjamin’s famous thesis, within the hypocritical Wilsonian automaton babbling about freedom and democracy sits a hunchbacked, Hamiltonian chess-playing dwarf, guiding by strings an imperial puppet whose idol is always profit and the reproduction of capital.

It is worth reiterating the foreign policy of the US — that country to which the fictional champion of the working class, Frank Sobotka, referred to when he said, “We used to make shit in this country, build shit. Now all we do is put our hand in the next guy's pocket.”12 — has never perceived a disconnect between its values and its interests. Therefore, discussing foreign policy traditions is merely arguing that money is the ultimate goal. If Mead’s typology has any capacity to describe Trumpism 2.0, it is to designate a Jacksonianism in form working for a particular Hamiltonianism in content. This is a Hamiltonianism for the era of new imperialism, that is, the era of financialisation, accumulation by dispossession, and the crisis-dispute phase of the US hegemonic cycle.

2. Trumpism as the radiating nucleus of reactionaries in the interstate system

Mead, however, is right to argue that European realpolitik is ineffective when it comes to providing a foundation for US Grand Strategy when faced with the crisis-dispute phase of its hegemonic cycle. As Anderson pointed out, the dichotomy between Wilsonian idealism, centred on “an idealist commitment to put an end to arbitrary powers everywhere,” and Rooseveltian realism, whose purpose is to “maintain a balance of power in the world,” rested on a Hamiltonian foundation, according to which the raison d'être of US foreign policy is “the pursuit of American supremacy, in a world made safe for capital.”13 Therefore, Trump 2.0’s Jacksonian Hamiltonianism, on the one hand, accounts for the loss of power of the Wilsonian Hamiltonianism in place since the Ronald Reagan administration through to Joe Biden’s administration and, on the other hand, expresses the need to find another amalgam of values and interests for US power as the modern interstate system heads towards a phase of hegemonic dispute marked by the emergence of new power configurations on a global scale.

Precisely because it was presented to explain an analogous situation in the interstate system, we believe that the typology developed by Arno Mayer in Dynamics of Counterrevolution in Europe, 1870-1956 offers a heuristic framework for understanding the forces at play in contemporary world politics.14 In Mayer’s analysis, the consequences of World War I created the conditions for the interstate system to descend into chaos, as it generated the conditions for a surge in working-class rebellion while simultaneously fostering a rise in struggles for the right to national self-determination. The Russian Revolution was the result and synthesis of both aspects. The Great War also provided the stage for the revanchism of the defeated Great Power, Germany. Consequently, world politics shifted into a power struggle where Britain and France championed the preservation of the status quo — namely, free-trade imperialism — while Nazi Germany became the champion of reactionary forces. The Stalinist Soviet Union, for its part, was the nucleus of revolutionary forces even if, paradoxically, it represented counter-revolution on a national scale.15

If we turn to Mayer's typology at a time when the locomotive of the interstate system seems headed for chaos, what are the conservative, reactionary, and revolutionary forces within it? The scope of this question exceeds this text. What is relevant here, however, is that, unlike the previous phase of hegemonic struggle within the interstate system, when Britain chose to preserve or defend the system it had created, the US under Trump has become the radiating nucleus of reactionary forces against the neoliberal world order that emerged in the 1980s. Therefore — and there is more than one paradox in all of this — the “MAGA International” brings together those seeking revenge against the consequences of monetarist counterrevolution, financialisation, and neoliberal globalisation. In other words: the Trumpist counter-revolution brings together the losers of the previous counter-revolution in the West, from which the Communists in China emerged victorious in the medium term.

Like the heirs of the losers of the Great War, Trumpism unites reactionary forces that believe the best way to confront the reordering of the global political economy brought about by China’s geoeconomic and geopolitical rise — and the corresponding rebellion and rise of the subordinate classes of the Global South — is by transforming the old regime from within, rather than preserving it as Bush Jr, Obama, and Biden aspired. In essence, the “MAGA International” is rebelling against a Western world in ruins, a world bequeathed to them by their idols: Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, Milton Friedman, and Augusto Pinochet.

- 1

See G. Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money and Power at the Origins of Our Time , Madrid, Akal, 1999, Chapter I.

- 2

W. R. Mead, Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How it Changed the World , New York, Routledge, 2009.

- 3

P. Anderson , Imperium et Consilium: North American Foreign Policy and Its Theorists , Madrid, Akal, 2014, p. 125.

- 4

W.R. Mead, “The Jacksonian Revolt: American Populism and the Liberal Order,” Foreign Affairs , January 20, 2017. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/north-america/jacksonian-revolt .

- 5

W.R. Mead, “Andrew Jackson, Revenant,” The American Interest , January 17, 2016. Available at: https://www.the-american-interest.com/2016/01/17/andrew-jackson-revenant/

- 6

W. R. Mead, Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How it Changed the World , cit., p. 220.

- 7

Ibid ., pp. 245-246.

- 8

S. Žižek, Parallax Vision , Buenos Aires, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2011, p. 228.

- 9

P. Anderson , Imperium et Consilium: North American foreign policy and its theorists , cit., p. 127.

- 10

W.R. Mead, “The Return of Hamiltonian Statecraft,” Foreign Affairs , Hudson Institute, August 20, 2024. Available at: https://www.hudson.org/foreign-policy/return-hamiltonian-statecraft-walter-russell-mead

- 12

A. Hamilton, “Final Version of the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, [5 December 1791],” Founders Online, National Archives. Available at: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-10-02-0001-0007

- 13

P. Anderson , Imperium et Consilium: North American foreign policy and its theorists , cit., pp. 126-127.

- 14

A.J. Mayer, Dynamics of Counterrevolution in Europe, 1870-1956: An Analytic Framework , New York, Harper & Row, 1971.

- 15

See G. Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money and Power at the Origins of Our Time , op. cit., pp. 84-85.