Spain: As Podemos and United Left join forces, is a left government in sight?

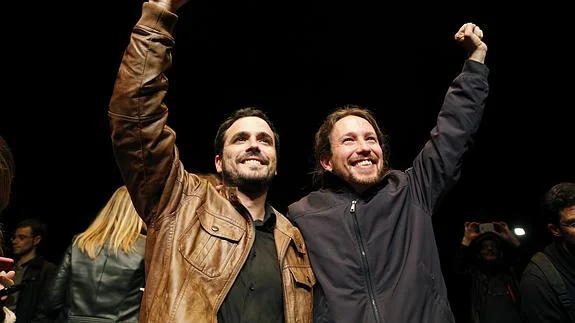

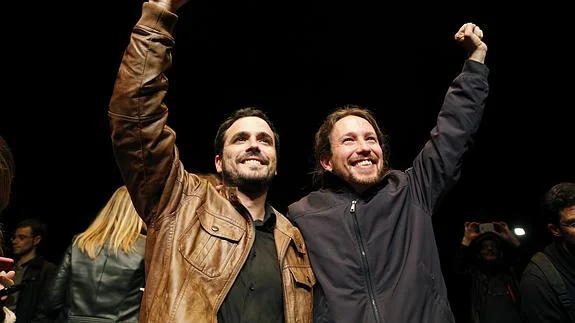

United Left (IU) spokesperson Alberto Garzón and Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias.

By Dick Nichols

May 31, 2016 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal a much shorter version of this article was first published at Green Left Weekly — Five months after the December 20 election in Spain failed to produce a government, the country is returning to the polls in the most polarised contest since the end of the Franco dictatorship in 1977.

The stakes could not be higher. The “second round” election on June 26 could open the door to the final breakdown of the two-party system and the beginning of a deep-going democratisation of the Spanish state and politics: or it could drive all parties defending the status quo into a last-ditch alliance against the forces for radical change.

The December 20 poll saw a surge in support for the radical party Podemos and the various regional coalitions in which it participates. However, the final vote for these new forces — born of the last five years of struggles in defence of social and national rights — still fell short of the vote for the social-democratic Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) by 20.66% to 22.01%.

Nonetheless, the total vote to the left of the PSOE — including the older radical coalition United Left (IU), the Basque left-nationalist EH Bildu and the Catalan centre-left Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) — was 27.59%. Spain underwent a political shift as the overall left vote reached 52.4% as against 47.6% for the right (53.6% to 46.4% if we exclude the Catalan nationalist right, which would support a left government for Spain in exchange for a Scottish-style referendum for Catalonia).

With this result it was arithmetically possible, on condition of some minimum support from Basque and Catalan nationalist forces, to form a left government of PSOE, Podemos and IU.

But that was never going to happen: the leadership of the Spanish-centralist PSOE is as hostile to participating in a left government it doesn't control as it is to acknowledging the right of self-determination of the nations that make up the Spanish state.

After December 20, PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez chose instead to negotiate a proposal for a “government of change” with the “hipster” neoliberal party Citizens, which he himself had dubbed “extreme right” during the election campaign. (Citizens’ dream for Spain is to turn it into a “normal” European power purged of its endemic corruption, labour market “rigidities” and troublesome nationalisms.)

In response, Podemos, its allies and IU voted down the formation of a PSOE-Citizens administration — and were rewarded with virulent PSOE abuse for being “accomplices” of the ruling People's Party (PP). As for the PP, still the largest force with 28.72% after December 20, it was never going to support a minority PSOE-Citizens administration that removed PP hands from their rightful place on the levers of power.

Towards left unity

New elections then became inevitable, and by early May Spain seemed set for a repeat of December 20. However, the refusal of the PSOE to negotiate in good faith to its left focussed the attention of Podemos and IU on the critical problem — how to overtake the PSOE and be better placed to pressure it into supporting a left government.

In the run-up to December 20, IU had campaigned for a united ticket of all left and progressive forces, only to be rebuffed by a Podemos leadership that judged that identification with an IU influenced by the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) would damage its chances with voters disgusted with the traditional parties but not identifying as left.

Podemos only stood together with IU on tickets where other forces were present: in Galicia, where the other main component of the In Tide coalition was the left-nationalist party Anova and in Catalonia, where the two parties' Catalan affiliates were part of the Together We Can five-party coalition hegemonised by Barcelona Together (the movement which had succeeded in winning the city council in the May local government elections) and including the region's main left force, Initiative for Catalonia.

In the Valencian Country, where Podemos ran with the Valencianist formation Commitment (itself a coalition of left, Green and left-nationalist forces), the local IU affiliate was excluded from the united list, even though it had wanted to be part of it. In addition, the Podemos leadership insisted that the word “Podemos” should appear in the names of the broader coalitions, succeeding in Catalonia and the Valencian Country, but failing in Galicia where the authority of historic Galician nationalist leader Xosé Manuel Beiras prevailed in imposing the name “In Tide” (a reference to the “tides” of resistance to austerity and attacks on Galician national rights).

The resistance of the Podemos leadership to forming a direct electoral partnership with IU took place despite pressure from its own ranks, reflected in Podemos local leaders signing an appeal for “people's unity” launched by several hundred figures from the social movements and the spheres of culture and art.

IU's response to being snubbed by Podemos was to campaign as the “real left” on a ticket called People's Unity Together, and to stress those issues on which Podemos had shifted its positions since the May 2014 European elections in which it first burst into prominence (such as debt restructuring and NATO membership).

In the light of the December 20 result, in which IU lost seats in all regions except Madrid but still maintained the support of 923,000 voters, the Podemos leadership reopened negotiations with the older radical force, in effect conceding that its rejection of unity had been mistaken (or that its attempt to eliminate its older rival had failed). These discussions led to the proposal for a single list in all those regions where the two parties had stood against each other in the “first round”. The joint ticket, called United We Can, was endorsed by 98% of Podemos members and 87.8% of IU members, as well as by 92% of the green party Equo (the third all-Spanish party involved in the negotiations).

The lower degree of support by IU members reflected lingering resentment and distrust of Podemos. This distrust had been more sharply on display in a prior split in the IU's Madrid organisation, which had to be “refounded” by the IU federal leadership in order to isolate those most opposed to unity with Podemos.

On May 3, former IU national coordinator Gaspar Llamazares said that the agreement could convert IU “into a satellite of an unknown planet that today is left, tomorrow is right”. He added that “IU is very weakened from all points of view and will see itself overtaken. It will have neither a parliamentary group nor a spokesperson and will be part of a divided Podemos. After four years without a spokeperson and in the medium term it could become part of Podemos or a formation dependent on Podemos, without a life of its own.”

IU spokesperson Alberto Garzón replied that convergence between Podemos and IU was unavoidable if the PSOE was to be overtaken, and that “neither Llamazares or Garzón decide these things, but the IU membership”. He was supported by Gerardo Iglesias, the IU's first federal coordinator, who said on May 25 that the resistance to IU standing together with Podemos repeated 30 years later the reluctance of a minority in the PCE to abandon standing in its own name instead of inside the then newly-founded IU.

Election lists and platform

The result of the negotiations now means that voters will have single tickets to the left of the PSOE in 14 of the Spanish state’s 17 administrative regions (“autonomous communities”).

In 11 of these regions, the list will be United We Can, while in Galicia, Catalonia and the Valencian Country the all-Spanish parties will be part of broader coalitions. These coalitions — Together We Can (Catalonia), In Tide (Galicia) and A La Valenciana (Valencian Land) — had already stood with great success on December 20 (A La Valenciana as Podemos-Commitment).The United Left in the Valencian Country will now be part of A La Valenciana.

On the Balearic Islands, the green left coalition More For Mallorca (MES), part of the ruling coalition in the regional government, will be represented on the United We Can ticket.

United We Can and the broader coalitions will face competition from left and centre-left nationalist candidacies only in the Basque Country (EH Bildu), Catalonia (ERC) and Galicia (We-The Galician List).

IU has been guaranteed one sixth of the MPs elected on United We Can tickets, independent of any IU MPs returned on the three broader lists. With this agreement IU should win parliamentary representation that roughly corresponds to its real level of support, as against the meagre crop of two MPs it managed in December under the rigged Spanish system of uneven-sized multi-member seats.

For its part, Podemos has used the creation of United We Can to present new candidates who have long been in favour of left unity, but had hitherto been reluctant to appear on either Podemos or IU lists. They included Manuel Monereo, long-standing PCE member and well-known left intellectual, and Diego Cañamero, combative leader of the Andalusian Workers Union (SAT). Both Monereo and Cañamero were active in creating the Marches For Dignity, which in March 2014 brought over a million into the streets of Madrid in support of “bread, work and a roof for everyone”.

All forces making up the joint tickets will stand on the platforms they presented in the December poll. However, they have also adopted a 50-point common platform called “Changing Spain: 50 Steps for Governing Together”, containing practical measures addressing the key problems of Spanish society.

The platform’s immediate economic focus is boosting public expenditure focused on energy sustainability, job creation and poverty reduction, which is to be funded through a war on tax evasion, higher taxes on the rich and by reducing the European Union's deficit reduction targets for Spain.

Social measures include an end to evictions, guaranteed access to water and electricity and increased funding for education and health. Democratic reforms cover a referendum for Catalonia, a citizen debate on constitutional reform (which would confront issues like the Spanish monarchy and NATO membership), and a one-vote-one-value electoral system.

The platform also includes comprehensive proposals on environment and commitments to a European debt conference, recognition of Palestine, self-determination for the Western Sahara and international aid funding set at 0.7% of GDP.

Stopping the reds

United We Can is spooking the Spanish powers-that-be. The average of opinion polls since its formation has the new coalition and related alliances in second place behind the PP at 24.1%, as against the PSOE's 20.8%. In terms of seats, United We Can and the PSOE are neck-and-neck at around 80 seats apiece (around 10 less for the PSOE and 10 more for United We Can).

A May 29 Metroscopia survey of voting intentions in 11 strategic voting districts (provinces) had United We Can and the broader coalitions picking up mainly in Barcelona (where Together We Can would go from 9 to 12 seats) and Valencia (where A La Valenciana would go from four to five).

United We Can would also pick up seats in provinces where the non-PSOE left has never won representation (in the Castilian districts of Guadalajara, Albacete and Ciudad Real), and increase its representation in Andalusian districts. This last result is despite the quite hostile relations between IU and Podemos in that region (according to Metroscopia the only one where the combined vote of United We Can could be less than the separate vote from Podemos and IU on December 20).

And this is before the formal election campaign, where Podemos and IU are at their best, has begun. In the December campaign, Podemos and the coalitions in which it participates increased their support from 15% to 20% in two weeks leading up to election day.

Key will be the rate of participation: the more the United We Can campaign inspires people to vote in spite of the “all-politicians-are-the-same” mood presently being fostered by the media, the greater will be the support for the radical coalitions. United We Can will be able to bring valuable assets to that fight — including the mayors of the “councils for change” in Barcelona, Madrid, Cadiz, Zaragoza and A Coruña.

It is no surprise, then, that while the PP, PSOE and Citizens are each struggling to extend their share of the vote, that fight is now constrained by their shared goal of arresting any surge to United We Can. This state of affairs guarantees a dirty war of fear, loathing and red-baiting over the next month.

As a prelude, the connections, real and imagined, of Podemos leaders with Venezuela's Bolivarian government are once again being scoured by squads of “investigative journalists” from the mainstream media.

On May 24, Citizens' leader Albert Rivera began his Spanish election campaign in the Venezuelan capital Caracas, as honoured guest of the anti-Bolivarian majority in the country's national assembly! This majority also invited Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias to appear before them and explain his links with Bolivarianism.

On May 22, PP leader Pablo Casado denounced Podemos' “Caracas project, of empty shelves, of chemists where 200 people wait to buy aspirin, of communications media closed down, of business people with their businesses expropriated, of citizens with their second home expropriated.”

He added that the only “useful vote” on June 26 would be for the PP, so as to avoid Podemos “beating the PSOE and the PSOE having to support him [Iglesias] as prime minister, as it has done in the councils where they govern together, like Madrid and Barcelona.”

Not to be outdone by their competitor on the right, on May 27 the PP-led acting government of Spain declared that it would be keeping a special eye on Venezuela, and the interests of the 120,000 Spaniards living there.

This strategy of demonising IU-Podemos as a threat to the stability, security and unity of the Spanish state may be successful in drawing some of the right-wing vote back from Citizens (PP support is rising in the latest polls). However, it remains to be seen whether it will succeed in shifting the overall social balance back to the right — given the PP’s brutal record in government, the enormous corruption scandals in which the party is mired (and which will continue to break during the election campaign) and an economic “recovery” yielding no benefit for the vast majority.

PSOE troubles

As for the PSOE, on May 24 Pedro Sánchez joined in the Venezuela-baiting with the claim that Iglesias had to explain the financing of a Podemos-related foundation that had supposedly received Venezuelan funding. He also required the Podemos leader to justify why he had called recently released Basque left-nationalist leader Arnaldo Otegi a “political prisoner”.

Sánchez had previously rejected a Podemos offer to run a PSOE-IU-Podemos joint ticket for the Senate as a way of breaking the PP's absolute majority in Spain’s upper house. He has also started to launch PP-style attacks against the “councils for change” in Barcelona, Madrid and other cities (despite the local PSOE sometimes supporting them!)

Sánchez faces a challenging job in convincing voters that the PSOE is a reliable anti-PP force, given that he did the deal for government with Citizens (the “PP lite”) and that many PSOE identities have openly called for a grand coalition of Spain's “parties of government”.

He will also have a tough time explaining why a party that claims to oppose everything the PP stands for cannot participate in a left government, especially as popular support for the PSOE's big pretext for refusal to take part — a referendum for Catalonia — continues to grow, to the point that important figures in the PSOE's Catalan affiliate are having to support it.

The risk the PP, PSOE and Citizens all run is that Iglesias and Garzón will be able to present a calm and rational case for voting United We Can as the only feasible way of at once addressing the governmental deadlock, reversing austerity and beginning to treat the chronic illnesses of Spanish state institutions.

They would in this way also expose the underlying motivation of the PP-PSOE-Citizens fear-and-loathing campaign—to frustrate any change that would make Spain's economic elites pay for improving the lives of the millions afflicted by the economic crisis.

The United We Can's campaign will depend critically on its ability to inspire, mobilise and organise supporting activists. If this effort succeeds, after June 26 the PSOE will face the choice it is desperate to avoid: near-certain oblivion following entry into a grand coalition with the PP or left government on terms set by United We Can.

Dick Nichols is the European correspondent of Australia's Green Left Weekly and Links—International Journal of Socialist Renewal, based in Barcelona.