COVID-19 vaccines: Stories of monopoly, blackmail and inequality

By Randy Alonso Falcón and Edilberto Carmona Tamayo. Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann.

March 26, 2021 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from CubaNews — The apprehensions raised in some countries by the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine, the US dirty campaign against the Russian Sputnik V and the confirmed refusal of the most powerful nations to let their pharmaceutical companies temporarily release the patents of their antidotes against COVID-19, have further strained the availability of vaccines and deepened the profound differences in the right to life between the powerful and the poor in this world.

Never before has a health emergency struck so many in so many places and in such a short space of time. COVID-19 has already affected more than 120 million people in the world and has caused the death of more than 2.6 million human beings.

Such a universal challenge warranted a global and coordinated response. But once again, contrary to the demands of the UN and the World Health Organization, nationalism, pettiness, the overwhelming power of transnational corporations and every person for themselves, have prevailed.

Vaccines seem to be the only effective barriers against the pandemic. Only immunization of a majority of the world’s population could put a stop to the growing transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. But neither the pharmaceutical transnationals nor the governments of the rich world have that vocation for collective response and global solidarity.

Who can develop and produce vaccines?

The pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry suffers from high concentration and transnationalization. Large companies from developed countries and emerging economies monopolize drug research, production and distribution. Nine of them are among the 100 companies that generate the highest revenues worldwide.

According to Euromonitor Global, the pharmaceutical industry is responsible for almost 4% of global production activity. If it were a country, it would be among the 15 richest economies on the planet. Almost half of the sector’s total sales come from China and the USA, followed by Switzerland, Japan, Germany and France.

The production of vaccines, in particular, concentrates in 4 large firms more than 80% of the market, according to 2019 data: the British GlaxoSmithKline, the American Merck Sharp & Dohme and Pfizer, and the French Sanofi.

That global market generated in 2018 some $37 billion and it is estimated that by 2027 it will exceed 6$4.5 billion.

As is remarkable, underdeveloped nations -which are the vast majority-, have hardly any capacity to develop their own vaccines (Cuba is one of the few honorable exceptions) and no productive capacities of their own. This has left them with little room for maneuver to influence the uneven development of vaccines in the midst of the pandemic.

How have the vaccines against COVID-19 been financed?

Since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, it has been calling for a concerted and joint solution to the threat. But the wrathful logic of the market dictates the course of our world and what has taken place since then is a frantic race to hit the bull’s eye (immune and financial), in which there has been no shortage of obstacles, pressures and even blackmail.

From the outset, the major powers allied themselves with the major pharmaceutical corporations in order to conveniently manage the discovery of a solution that would allow them to emerge with an advantage from the health and economic crisis ravaging the world.

Governments provided at least $8.6 billion for vaccine development, according to analyst firm Airfinity. The US, EU and UK invested billions in AstraZeneca’s vaccine, developed by Oxford University. Germany invested $445 million in the vaccine developed by Pfizer and its German partner, BioNTech. Moderna’s vaccine was fully funded and co-produced by the U.S. government.

While philanthropic organizations contributed $1.9 billion. Individual personalities such as Bill Gates, Alibaba founder Jack Ma and country music star Dolly Parton made contributions.

Only $3.4 billion has come from the pharma companies’ own investment, part of which has also come from external funding.

Despite the fact that Big Pharma has only provided one third of the funding, who is reaping the economic benefits? Who has set the rules of the game in the distribution of vaccines?

Foul Play

To obtain the vaccine against COVID became, beyond the health interest, a geopolitical objective. Whoever managed to get the vaccine would capitalize on its commoditization and whoever had more financial resources would be able to monopolize more immunizations.

Scandalous was the news of the Trump administration’s maneuver, as early as March 2020, for the German company CureVac -which had begun to research a possible vaccine-, to leave its headquarters in the European country and move to the U.S. in exchange for “large amounts of money”.

As it had also acquired PCR tests, pulmonary ventilators, masks and biosafety equipment, Washington also set out from the beginning to acquire the production and distribution of vaccines.

This was coupled with sometimes subtle, sometimes overt, smear campaigns against Russian and Chinese vaccine candidates in a concerted attempt to shut them out of other markets. Many doubts were cast on the speed of development, quality of clinical trials and effectiveness of the candidates from both nations, especially against Sputnik V from Gamaleya Laboratories.

A nurse prepares a Sputnik V injection at a Moscow clinic. Photo: AFP

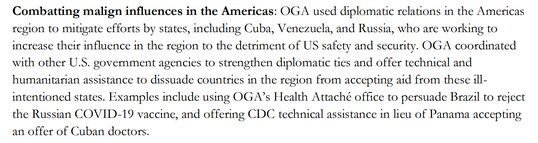

After Russia’s leading vaccine was certified by its authorities and sparked interest in several nations, the United States and the European Union have been tripping it up all over the place. The 2020 Annual Report of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recently revealed that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recently revealed that the Office of Global Affairs (OGA) used the Office of the Health Attaché in Brazil to persuade the government of that South American country to “reject the Russian COVID-19 vaccine”.

Text subtitled as Combating malign influences in the Americas. Photo Screenshot of HSS annual report

In response to the revelation, Russian presidential spokesman Dimity Peskov stated: “In many countries, the scale of pressure is unprecedented (…) such selfish attempts to force countries to abandon some vaccines lack perspective. We believe that there should be as many doses of vaccines as possible so that all countries, including the poorest, have a chance to stop the pandemic.”

The European Union, for its part, has not yet given the green light to the Russian vaccine for use in its member countries, even though that region has lagged behind the US, Canada, the UK and Israel in vaccine availability, and even though the prestigious health journal The Lancet acknowledged the high efficacy of Sputnik V in a publication.

Beyond such barriers, Russian and Chinese vaccines have been gaining ground in different regions, due to their effectiveness and the global shortage of immunizers. Slovakia even left the European Union fold to acquire 2 million doses of Sputnik V and Hungary, which has also approved the use of the Russian vaccine, acquired doses of the Chinese Sinopharm, which has also not received the green light from the European Medicines Agency.

Health workers in Indonesia unload a shipment of Chinese vaccine Sinovac

Blackmail without anesthesia

The States made the major investment, but BigPharma imposes the conditions and keeps the revenues. The monopoly of a few multinationals in the procurement and production of anti-COVID-19 vaccines gives such companies overwhelming power.

Recent reports show how pharmaceutical giant Pfizer has attempted to impose onerous conditions on Latin American nations to supply them with certain quantities of its injectable.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro showed his displeasure these days at Pfizer’s demands on his government, pointing out that among the conditions set by the consortium is a clause in the purchase contract that exempts it from “all liability” for possible side effects of its immunizer.

“We have been very hard and they have been very hard on us. They won’t change a comma. The government is dealing with this together with Congress and it is being discussed in terms of a relaxation of the law”, said the recently dismissed Brazilian Minister of Health, Army General Eduardo Pazuello.

Argentina, Peru and the Dominican Republic also suffered intense pressure from Pfizer, as shown in an investigation by The Bureau Investigative Journalism.

Pfizer representatives in Buenos Aires demanded indemnification against any civil claims citizens might file if they experienced adverse effects after being vaccinated. “We offered to pay for millions of doses upfront, we accepted this international insurance, but the last request was extraordinary: Pfizer demanded that Argentina’s sovereign assets also be part of the legal backing,” an Argentine official confessed. “It was an extreme demand that I had only heard when the foreign debt had to be negotiated, but in that case as in this one, we rejected it immediately.”

The Argentine government believes that Pfizer’s demands were part of a commercial strategy that favored sales to developed countries and not to Latin American countries.

There are several voices that warn that the urgency to have vaccines available for a disease that has left so many dead in the world may have led some governments to accept significant limitations on their responsibilities and demand transparency on the agreements with pharmaceutical companies.

Professor Lawrence Gostin, director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for National and Global Health Law said, “Pharmaceutical companies should not use their power to limit life-saving vaccines in low- and middle-income countries” and noted that liability protection should not be used as “the sword of Damocles hanging over the heads of desperate countries with desperate populations”.

Even mighty Europe seems to have felt the pressures. Although EU agreements with vaccine manufacturers are kept with their main clauses secret, the Vaccine Procurement Strategy made public by the European Commission states that “the responsibility for the development and use of the vaccine, including any specific compensation required, will lie with the procuring Member States.”

Excerpt from the contract for the purchase of vaccines from CureVac by the European Commission was disclosed with all essential parts blacked out.

Who will be able to be vaccinated in 2021?

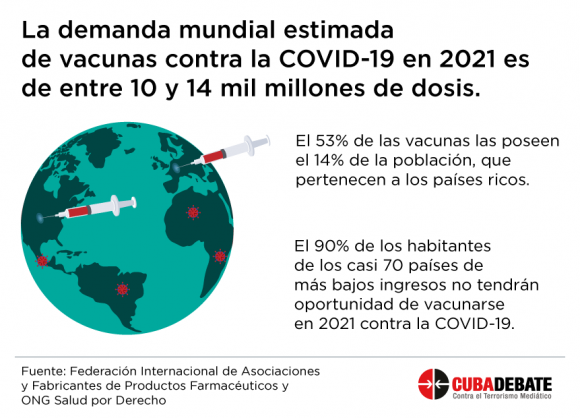

Vaccine production capacities in the world are insufficient to have the necessary doses this year to immunize the world’s population. The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) says that the estimated global demand for vaccines in 2021 is between 10 and 14 billion doses.

According to statistics cited by data firm Statista, the United States can produce nearly 4.7 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine and India more than 3 billion potential doses. China, previously not a major player in the vaccine export market, has committed to manufacturing more than 1 billion doses.

Great Britain, Russia, Germany and South Korea are also among the established manufacturing centers, but with lower production capacity.

Vacuna Johnson & Johnson. Photo: Reuters.

Given this reality, the inequity and injustice of today’s world are once again evident: the richest countries have purchased most of the vaccines that will be produced in 2021 (even for stockpiling), while poor nations will not have doses to administer even to their most vulnerable segments of the population. More than 100 nations are waiting for the first bulb to arrive.

It is estimated that 90% of the inhabitants of the nearly 70 lowest-income countries will not have the opportunity to be vaccinated against COVID-19 this year.

The most powerful nations took advantage of their purchasing power and investments in vaccine development to secure supplies of the coveted antidote.

So far, about 12.7 billion doses of various coronavirus vaccines have been pre-purchased, enough to vaccinate approximately 6.6 billion people (except for Johnson & Johnson’s, all vaccines approved so far require two doses).

More than half of those doses, 4.2 billion insured, with the option to buy another 2.5 billion, have been purchased by wealthy countries that are home to only 1.2 billion people.

Canada has bought enough doses to inoculate every Canadian five times, while the U.S., U.K., EU, EU, Australia, New Zealand and Chile have bought enough to vaccinate their citizens at least twice, although some of the vaccines have not yet been approved.

Israel struck a deal for 10 million doses and a promise of a steady supply from Pfizer in exchange for data on vaccine recipients. According to reports, the country also paid $30 per dose, double the price paid by the EU.

As Irene Bernal, a researcher on access to medicines at the NGO Salud por Derecho, told the newspaper El País last December, “we are seeing that whoever has the money is the one who has the access. We have kept 53% of the vaccines for 14% of the population, the rich. And the companies have a limited production capacity, so when are the doses going to reach the poorest countries?”

Design: Edilberto Carmona tamayo

Low- and middle-income countries, with 84% of the world’s population, have made deals directly with pharmaceutical companies, but have so far secured only 32% of the supply.

“We are in such a massive crisis,” said Fatima Hassan, founder of the South African Health Justice Initiative. “If even in South Africa we can’t vaccinate half our population soon, I can’t even imagine how Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Namibia and the rest of Africa will cope. If this is going to go on for another three years, we won’t get any kind of continental or global immunity.”

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador and his Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard have asked the U.S. authorities to allow them to acquire part of the tens of millions of AstraZeneca vaccines produced in the United States, which Washington has stockpiled without having approved the use of this drug. Other countries that have already authorized this vaccine are begging to have them.

Mexico, one of the countries with the largest presence of COVID-19, has so far administered some 4.4 million doses using Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sinovac and Sputnik V vaccines, in a population of more than 128 million inhabitants, which means a low vaccination rate, according to the website www.ourworldindata.org managed by the University of Oxford.

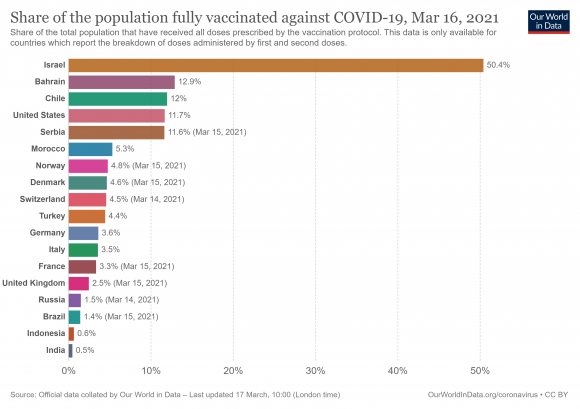

The most current statistics from this observatory show the low proportion and unequal distribution of the number of fully vaccinated people (with all the necessary doses) in the world:

Percentage of population fully vaccinated with required doses by country, March 16, 2021. Graphic: OurWorldinData /Oxford University

According to data collected by Bloomberg, as of Thursday, more than 410 million doses of anti-COVID vaccines have been administered worldwide in some 132 countries. This represents just 2.7% of the world’s population.

| % of population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Doses administered | Enough for % of people | given 1+ dose | fully vaccinated | Daily rate of doses administered |

| Global Total | 410,697,435 | – | – | – | 9,959,983 |

| U.S. | 115,730,008 | 17.7 | 22.7 | 12.3 | 2,503,731 |

| China | 64,980,000 | 2.3 | – | – | 960,000 |

| EU | 54,084,195 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 3.6 | 1,236,527 |

| India | 38,920,259 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 1,835,249 |

| U.K. | 27,614,526 | 20.7 | 38.5 | 2.8 | 458,471 |

| Brazil | 14,936,060 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 1.9 | 357,115 |

| Turkey | 12,707,210 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 5.7 | 306,998 |

| Germany | 10,067,955 | 6.1 | 8.4 | 3.7 | 233,813 |

| Israel | 9,609,766 | 53.1 | 57.1 | 49.1 | 76,526 |

| Russia | 8,500,000 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 100,000 |

| France | 7,927,771 | 6.1 | 8.7 | 3.5 | 214,391 |

| Chile | 7,907,275 | 20.7 | 27.9 | 13.5 | 290,378 |

| Italy | 7,330,104 | 6.1 | 8.4 | 3.8 | 178,874 |

| UAE | 6,980,466 | 32.5 | – | – | 81,874 |

| Indonesia | 6,787,283 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 256,516 |

| Morocco | 6,499,476 | 9.1 | 12.0 | 6.3 | 199,542 |

| Spain | 5,993,363 | 6.4 | 8.8 | 4.1 | 117,322 |

| Poland | 4,738,902 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 4.4 | 72,826 |

| Mexico | 4,737,622 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 178,501 |

Note: Population coverage accounts for the number of doses required for each vaccine administered. The daily rate is a 7-day average; for countries that don’t report daily, the last-known average rate is used.

Vaccine Apartheid

Design: Edilberto Carmona Tamayo

Scientists and activists warn that we are heading towards a “vaccine apartheid” in which people in the global South will be vaccinated years later than those in the West.

Not only will poorer countries be forced to wait, but many are already being charged much higher prices per dose. Uganda, for example, has announced a deal for millions of vaccines from AstraZeneca, at a price of $7 a dose, more than three times what the European Union paid for it. Including transport fees, it will cost $17 to fully vaccinate a Ugandan.

The effects of this inequity would be severe. A model developed by Northeastern University indicates that if the first 2 billion doses of Covid-19 vaccines were distributed proportionally by national population, deaths worldwide would be reduced by 61%. But if the doses are monopolized by 47 of the world’s richest countries, only 33% fewer people would be saved.

Scientists are also concerned that if there are countries that will not be able to immunize a large part of the population, there will be more opportunities for the virus to continue mutating and deaths will increase in these under-vaccinated countries, making the available vaccines less effective over time.

As WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus noted earlier this year, “…we face a real danger that, while vaccines bring hope to some, they become one more brick in the wall of inequality between those who have resources and those who do not.”

A restrained alternative

The difficulty in securing vaccine supply will make many poorer countries dependent on Covax, an organization created in April 2020, coordinated by WHO, the Coalition for Innovations in Epidemic Preparedness and GAVI, the international vaccine alliance.

Covax aims to administer 2 billion doses globally, including at least 1.3 billion for 92 low- and middle-income countries, by the end of 2021. This would be enough to inoculate 20% of each country’s population, with priority given to healthcare workers, the elderly and people with underlying medical conditions, although that target has been criticized as inadequate to deal with the pandemic.

Analysts estimate instead that Covax will at most provide between 650 million and 950 million doses, divided among 145 nations, including some of those with enough confirmed agreements for the vaccines to vaccinate their citizens multiple times such as Canada and New Zealand.

The pharmaceuticals have not delivered on their promises to COVAX and AstraZeneca, which was the main supplier is also facing its own particular situation of millions of doses withheld in the US and Europe.

Even Europe is not spared from the backlog

Germany suspended vaccination with AstraZeneca as of Monday 15. Photo: EPA Even the European Union is frustrated by the obstacles they have encountered in vaccinating their population. The only European vaccine so far, the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine, is in serious trouble after reports of some 30 cases of clotting problems in people immunized with the injectable. There are already 13 EU countries that have suspended vaccination with AstaZeneca, despite the fact that the WHO and the European regulatory agency defend its use as having more benefits than harmful impact.

To make matters worse, in the midst of the flare-up in the region, AstraZeneca had only delivered 25% of the agreed doses to the EU for the first quarter and Pfizer was also behind in its deliveries. In early 2021 Italy threatened to sue Pfizer for reducing by 29% the distribution of doses in that country. Now the European Commission announces that it has reached an agreement with Pfizer/BioNTech to bring forward 10 million doses for the second quarter of the year.

Despite the fact that BioNtech and CureVac are German, this European country has had problems with vaccination. The daily Der Spiegel pointed out a few weeks ago that “the European Union and Germany could run short of vaccine supplies. The delay in signing contracts with pharmaceutical companies could mean that the vaccines arrive late, as well as not being sufficient”.

The EU has so far administered 11 doses per 100 people, compared with 33 doses in the US and 39 doses in the UK, according to the Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker index.

The low availability and unequal distribution within the European Union has led countries such as Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Croatia and Latvia to publicly express their discomfort and ask for a “correction” in the distribution.

In view of the dilemma, the European Commission determined that the pharmaceutical companies which have vaccine factories in EU territories will not be able to export the products they generate to other regions if they do not receive permission to take them out of the country from the authorities of those nations.

Already on March 4, Italy, one of the countries hardest hit by the pandemic, took advantage of this EU decision to ban the export to Australia of 250,000 doses of Astrazeneca’s vaccine, which the Anglo-Swedish pharmaceutical company produced at its factory in Agnani, near Rome.

As frustrations grow more intense, some European officials are blaming the United States and the United Kingdom. European Council President Charles Michel said the U.S., along with Britain, “have imposed a total ban on the export of vaccines or vaccine components that are produced on their territory.”

Asked about this, Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, told reporters that vaccine manufacturers were free to export their U.S.-made products as long as they met the terms of their contracts with the [U.S.] government.

But because AstraZeneca’s vaccine was produced with help from the Defense Production Act, for which it received more than $1 billion in funding, Biden has to approve overseas shipments of its doses.

No holds barred for a round deal

The most powerful countries have put pharmaceutical profits above global immunity, despite political discourse that there will be no solution to the pandemic unless it is corralled worldwide.

Last week, on the same day marking one year since WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the US, EU, UK and Canada (all with sufficient vaccines secured) blocked the latest attempt by poor or middle-income nations to speed access to vaccines and treatments for COVID-19 by temporarily lifting World Trade Organization rules protecting intellectual property.

A resolution sponsored by South Africa and India and backed by 57 countries, which called for suspending during the pandemic parts of the TRIPS (Trade Related Protections for Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement that protects medical patents, was rejected by the bloc of rich nations. It had already met the same fate in discussions at the WTO in October and December 2020.

An agreement would have allowed underdeveloped or emerging nations to produce COVID drugs and vaccines without waiting for or adhering to licensing agreements with pharmaceutical companies that own the intellectual property of these medical products. This would have expanded the production of antidotes against the lethal disease and lowered treatment costs.

The governments of wealthy nations, the majority financiers of the anti-COVID vaccines, based their refusal on concerns that the release of intellectual property, even temporarily, could reduce incentives for corporate research and also questioned whether “developing” nations could begin production of the drugs soon enough to prevent the spread of the virus.

The truth is that Big Pharma multinationals were initially reluctant to fund COVID vaccine research because of the uncertainty of a race against time to get results and because of the poor cost-effectiveness of creating vaccines for health emergencies in the past.

The drugs sought by these companies are primarily those offered to citizens of wealthy countries, and especially those needed for chronic diseases requiring routine doses, which make them highly profitable.

But after they have seen the profitability that the durability in time of COVID-19 can leave them, they do not want now any limit to the “party” of income that they are enjoying in view of the urgent demand for vaccines.

Moderna reported that it has signed advance purchase agreements for more than US$18 billion for supplies to be delivered this year, while Pfizer projected nearly US$15 billion in revenues this year for its vaccine with BioNTech.

Boxes containing Modern COVID-19 vaccine are prepared for shipment at McKesson’s distribution center in Olive Branch, Mississippi, U.S., Dec. 20, 2020. Photo: Reuters

The main vaccine developers have benefited from billions of dollars in public subsidies, yet pharmaceutical companies have been granted a monopoly over their production, as well as over the profits they generate.

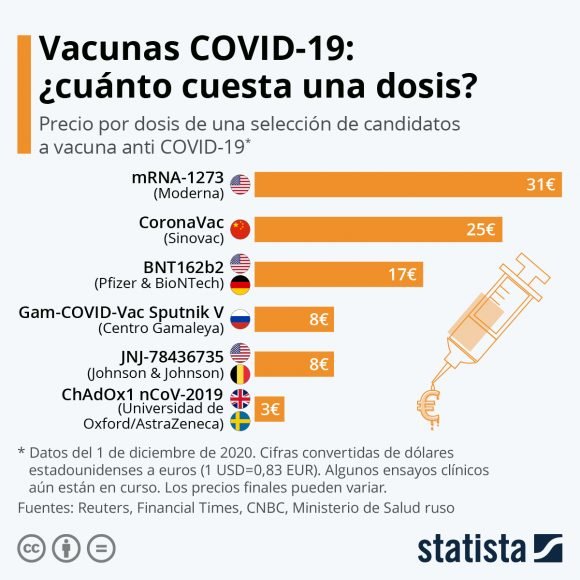

The prices at which vaccines are sold to different countries (they vary) are kept under the veil of secrecy of the agreements signed between pharmaceutical companies and governments, although the specialized website Statista has calculated the average price per dose at these amounts:

Multiply those numbers by the billions of doses required every x years (depending on the length of time these vaccines achieve immunity) and you can calculate how much the dance of the millions will amount to.

But, while pharmaceutical companies profit and control the pace and scope of vaccinations, the costs of the unequal distribution of vaccines to the global economy could be as high as $9 billion, according to Katie Gallogly-Swan, a researcher working with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

“It is unconscionable that in the midst of a global health crisis, huge multi-billion dollar pharmaceutical companies continue to prioritize profits, protect their monopolies and raise prices, instead of prioritizing the lives of people everywhere, including the Global South, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders aptly tweeted a few days ago.

“The world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure” has written the Director-General of the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, over here, we cross our fingers for Soberana and Abdala to immunize all of us, without distinction, before this year expires.

Randy Alonso Falcón, Cuban journalist, Director of the web portal Cubadebate, the site Fidel Soldado de las Ideas and the Cuban Television program “Mesa Redonda”. He directed other Cuban publications such as Somos Jóvenes, Alma Mater and Juventud Técnica. He received the Juan Gualberto Gómez National Journalism Award in TV in 2018. He has won several awards in the 26th of July National Journalism Contest. Email: director@cubadebate.cu On Twitter: @RandyAlonsoFalc.

Edilberto Carmona Tamayo, Chief of the Department of Multimedia Production, Monitoring and Innovation of Cubadebate and the Roundtable. Graduated in Journalism in 2016 from the University of Holguín. Contact: edilberto@cubadebate.cu On Twitter: @edctamayo