A generational challenge: Taming Amazon, renewing labour

First published at Socialist Project.

As the Occupy protests of 2011 exhausted themselves, a dramatic turn from protests to politics surfaced. In the US, the energy was channeled into Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. When this too was derailed, many of Sanders’ supporters turned, once more, to the labour movement as the foundation for radical social change.

From a historical perspective, these ‘turns’ marked an advance in the long march toward finding a new socialist politics. But the actual politics of the moment proved thin. Sanders’ supporters, for all their enthusiasm, seemed to be looking for an electoral shortcut to confronting ‘the system’ and state power. This was evidenced when, in the shadow of Sanders’ defeat, much of the movement he inspired returned to what they were previously doing or quietly melted away. Even the more substantive turn to unions tended to romanticize workers and their largely defensive, fragmented struggles.

Nevertheless, within this ferment were also groups of (mainly) young socialists, small in numbers but large in ambition, who came to more clearly grasp the limits of an electoral politics not backed by a substantive working-class base. Their priority was the long-term building, both widely and deeply, of that indispensable base. For a sub-set, this commitment to a rooted class politics coalesced in identifying Amazon as embodying the decisive challenge for this generation’s labour movement.

Amazon, they believed, could become a catalyst for larger changes in labour, changes that ranked with the CIO successes in the 1930s. They hired on in Amazon workplaces across the US and Canada or worked as external organizers. Their organizing was local but linked to networks of other regional chapters of like-minded socialists.

In considering this ‘Amazon Challenge’, two inter-related realities, controversial to many, are central: the depth of labour’s decades-long defeat and the identification of Amazon as the iconic 21st century corporation. Success at Amazon could make credible labour’s claim that “In our hands is placed a power greater than their hoarded gold.” Failure would consolidate labour’s defeats.

Parts I and II of this essay elaborate on the contextual realities of labour’s political defeats since the 1970s and Amazon’s recent conspicuous rise. This sets the stage for Part III and a discussion of strategic issues involved in taking on Amazon. The concluding section extends the discussion from barriers confronting the unionization of Amazon to the barriers confronting union organizing and the working class more generally.

Part I: Labour

Is labour winning?

A common refrain on the left asserts that the US labour movement is on the march again. The validity of this assessment is central to tackling any strategic orientation to labour. If labour is winning, then what’s needed is just to ‘keep on keeping on’. But if labour is not winning, then we need to shift gears and do something decidedly different.

Promising developments obviously exist. Recent victories at Starbucks demonstrate the stubborn will of baristas to unionize. And even if hopes at Starbucks don’t pan out, these committed young activists may move on to building for worker power elsewhere.

Especially significant was the United Auto Workers (UAW) pushing aside its past formulaic play-book in the last round of ‘Big Three’ bargaining in favour of a creative and disciplined bout of ‘organized chaos’. The UAW’s gains were impressive, but it was the union’s combative spirit that was the key, after two previous disappointments, to bringing Volkswagen’s Tennessee plant into the fold. This marked the first foreign-based auto assembly plant unionized in the US South, a region expanding in population and economic activity but especially hostile to unions. The momentum from the remarkable turnout (84%) and vote (three-one) was side-tracked by the defeat at Mercedes-Benz in Alabama, but is nevertheless likely to continue on to the unionization of tens of thousands other newly excited workers.

Nor do the UAW bargaining and organizing successes stop at the border between economics and greater social engagement. Moved by the horror of the bombings in Gaza and backed by the authority of the union’s recent successes (as well as the growing numbers of students and graduate assistants who are UAW members), UAW President Shawn Fain has spoken up forcefully in support of the protest encampments on university campuses.

These are not the only encouraging stories. Labour is certainly stirring, and the potential this points to is real. But after decades of defeats and stagnation, declarations of a definitive reversal – asserted so often and confidently over the years by left commentators – reflect a lowering of the bar measuring success, and underplay the reality of a labour movement still running to, at best, just keep up.

Seductive as the optimistic proclamations may be, labour struggles (some very important examples aside) are still generally localized, sporadic, and defensive, while labour’s power in the workplace, community, and politics remain unmistakably subordinate. Denying this in attempts to keep activists spirits up is no favour to labour. It obstructs an honest confrontation with what it might actually take to bring about and sustain the kind of labour movement we desperately need.

Consider this important marker. Work time lost to strikes as a percentage of total work time was indeed higher in 2023 than it has been since the turn of the millennium (2000). But comparing last year with an extended period in which labour was humbled speaks more to the accumulated lowering of worker and union expectations than to the birth of a new era. In the 1960s and 1970s lost time due to major strikes averaged more than three times that of 2023, and even this was followed in the 1970s with the aggressive and sustained assault on labour that still haunts working people.

Or consider union density. The level of unionization in the US stands at 10%, half of what it was in the early eighties (over that period, the labour force increased by some 50 million while the number of unionized workers stunningly fell by a third). US unionization is now below where it is estimated to have been a century ago, even further back if we look only at the private sector.

This is not surprising since so few breakthroughs have occurred in new sectors or among the most prominent corporations. Walmart’s unionization, for example, was identified not too long ago as a must for labour with anticipations of a unionizing leap forward in low-wage retail. Today, Walmart and its lesson seem no longer on labour’s radar.

In any case, the problem extends beyond stagnating unity density to the kinds of unions workers have built. In Canada, union density is now 29%, roughly triple the US. Yet that hasn’t led to a movement more dynamic than its American counterpart. Rebellions from below to open collective agreements and offset inflation have been rare. Rarer still have been wildcats over the accelerating pace of production.

Nor has Canadian labour built noticeably greater unity across unions and communities. An especially laudable illegal strike in November, 2022, by blue-collar education workers, the result of over eight months of education and organizing by their union, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), received rhetorical endorsement from other unions but not the level of support the struggle called for.

It was, of course, naive to expect more from the rest of the labour movement since other unions had not carried out similar advance preparations with their own members. But the more telling point is that the CUPE example didn’t spark a general emulation of the encouraging lesson staring labour in the face: workers, often taken for granted and underestimated, can be organized to challenge their circumstances and even the law.

The unionization in the US of some 400 dispersed workplaces at Starbuck’s (some 2.5% of the 16,000 Starbuck’s-owned or franchised coffee shops across the US) remains a good distance from representing practical workplace power. Even if Starbucks workers somehow manage to achieve a national collective agreement and becomes fully unionized, it would be a very significant and inspiring achievement, but it would not carry anywhere near the economic weight of organizing a corporation like Amazon.

The auto sector, on the other hand, carries great economic and social significance. The UAW is focussed on unionizing another 150,000 auto workers – an unambiguously impressive and even monumental objective by recent standards. But Amazon with its 1 million workers remains, like Walmart and other retailers, non-union. In measuring the overall state of labour, the rejuvenated spirit in the UAW has not, as yet, been taken up elsewhere.

As for the welcome swing in labour’s popular standing, caution is also in order. The recent positive attitudes to unions may, for example, be related to an extensive stretch of time without major periods of union-led disruptions in people’s lives. More important, the delegitimization of major American institutions – governments, political parties, the Supreme Court, the media, corporations whose ‘freedoms’ undercut workers’ freedoms, and (to some extent) the police – undoubtedly has something to do with support for oppositional groups. But this applies not only to unions but also the populist right, which – though often exaggerated – has also affected numbers of frustrated union members. This rise of the right, in all its complex forms, must be included in any assessment of whether labour is ‘winning’.

There is no denying the recent surprising empathy, and often active support, for strikes whether in the public or private sectors. This seems to confirm a greater acceptance of unions today. Yet as encouraging as this and other exciting signs of life in labour are, what they highlight isn’t yet a definitive renewal of unions and their public standing, but rather hopeful openings for advancing the as yet unrealized full potentials of the working class as a social force.

What is most telling about the state of labour is that even as some workers see partial victories, workers themselves generally know full well that working people are definitely not winning. Gross class inequalities grow worse; workloads continue to intensify; permanent insecurity is the dominant working-class reality as economic ‘progress’ spells not liberation, but threats.

Denying this reality in the name of inspiring workers is not organizing. It is spinning delusions. Inspiration without the strategies and collective capacities to realize them obscures all that needs doing to build the structures and practices that might bring genuine possibilities of success. That task also demands a sober consideration of the structural limits of unions.

Unions: A deeper dive

In responding to labour’s defeats, union leaders and sympathizers have pointed to a range of external causes – greedy corporations, hostile governments, globalization, competition from China, parasitic finance – and/or put their hopes in a reversal in the business cycle or in the political winds at long last improving the bargaining climate. All this is, of course, very relevant. But what unions have largely avoided, and still avoid, is asking, ‘What needs changing inside our own organizations if we are to cope and advance?’

There has consequently been, a few important examples aside, far too little discussion/debate involving members within and across unions about rethinking strategies, structures, and practices. Predictably, labour’s hesitancy in entering uncharted territories and investigating its own failures undermines developing the range of responses that might overcome its stagnation.

The left movement outside unions has, revealing its own limits, largely failed to penetrate and engage the labour movement or honestly re-evaluate their own missed opportunities. An overly-simplistic understanding of labour doesn’t help; for much of the left, labour weakness is reduced to a labour bureaucracy that constrains democracy and undermines worker militancy.

There are, no doubt, union leaders who have become comfortable with the curtailed expectations capitalism inflicts on workers. Lower expectations bring less pressure from below and sidestep the risk of new directions for the union. But putting all the blame on union leaders also tends to idealize workers and ignore workers’ own passivity. If deeply frustrated rank-and-file workers are so easily cowed by their elected leaders, why is it credible to imagine workers one day taking on the bosses, the state, and capitalism itself?

The point is that workers are neither inherently revolutionary nor inherently passive. They try to resist and survive in the hostile environment they find themselves in. Organizing – actively developing the power and confidence of the collective – is the decisive factor. In this regard, it’s imperative to note that unions emerge out of the working class but are not themselves class institutions. They are rather particularist organizations, representing groups of workers with different political outlooks and interests that happen to find themselves in specific workplaces.

The ‘solidarity’ of organized workers is biased to their own workplaces and perhaps their union or sector. This may have seemed adequate to making wage and benefit gains in the unique post-war decades, but it fell short for dealing with capitalism’s later restructuring of the economy, state, and the working class itself. In the new circumstances, the outcome of the democracy-militancy link without attention to class ideology cannot be assumed to be progressive. It can just as easily descend into what Raymond Williams dubbed ‘militant particularism’ – an indifference or even antagonism to wider class concerns. An example is that workers can make formally democratic decisions that, in populist fashion, ‘militantly’ challenge why their dues should support other struggles, movements, or international causes.

This overlaps with the drift – under the combined pressure from corporations determined to maintain their unilateral right to manage, the commitment of states to property rights, and the concern of workers to materially reproduce themselves and their families – to trade-off working conditions for wages and benefits. Just as particularism undermines a class orientation, this trade-off undermines the kind of daily involvement in shaping their lives that should be at the heart of workplace democracy. Rather than regularly challenging the reduction of their productive capacities to commodities, the debate is reduced to a periodic conflict over the price of their taken-for-granted subordination.

Moreover, while battles over working conditions tend to a decentralization of union activism and greater worker engagement, the bargaining of wages/benefits tends to a centralization of strategy to the top leadership, shrinking worker participation to ratification of outcomes brought to them and the occasional strike.

The marginalization of struggles over daily conditions reinforces bureaucratization at the top and relative passivity at the base, predisposing the worker-union relationship toward an insurance policy: workers pay a premium (dues) to an institution (the union) in exchange for ‘compensation’ (the accurate term for sacrificing control over your labour power for the more passive power of individual consumption). With little room for the direct participation and tactical disruption that is the oxygen of resistance, resistance atrophies.

Before linking this to the strategic response it might imply at Amazon, we need to establish why Amazon is, in Jane McAlevey’s parlance, such a key ‘structure test’ for the labour movement.

Part II: Amazon

Why Amazon?

There are no shortages of crucial campaigns that could significantly strengthen the labour movement. Ending America’s position as an outlier on universal healthcare and the UAW drive to make a truly momentous organizing breakthrough in the US south are only two such examples. The proposition that Amazon represents labour’s decisive challenge isn’t meant to downplay other campaigns. Rather, it reflects two distinctive attributes of Amazon: a) its socioeconomic dominance; and b) the special challenges posed in trying to unionize Amazon expressly suggest the strategic challenges faced in looking to the broader renewal of the labour movement.

We begin with Amazon’s pre-eminence. What makes Amazon iconic among capitalist actors is the combination of its scale, reach, and multi-dimensional dominance. (See forthcoming report on Amazon by Steve Maher and Scott Aquanno.) Amazon is the second largest private employer in the world, only surpassed by Walmart (though Amazon’s profits are higher). A sense of Amazon’s size can be gleaned from the fact that Amazon employs over one million workers in the US, 2.5 times the total employed by the largest fifteen US and foreign-based auto companies in the US (388,0000).

Amazon is an electronic shopping mall, the main go-to for on-line ordering. Sixty percent of US households include a subscriber to Amazon Prime with its free next-day delivery and video streaming for an upfront fee. (Global subscribers exceed 230 million.) It ranks second only to Netflix in video streaming and has 80 million music subscribers.

Amazon is also the leading global logistics company, delivering the packages ordered at home to your door. Along the way, its locational decisions and delivery routes are reshaping our cities and suburbs. It is as well a leader in amassing advertising revenue and spends more on research than any other corporation. It is by far the largest player in cloud computing services and has joined the race for AI supremacy.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance has pointedly noted that Amazon operates as a privatized public utility that other businesses can only access by paying a toll. Some 60% of Amazon packages come from third parties, with Amazon as the middle-man between the producer and the consumer raking in up to 50% of the final price (roughly 15% for platform use; 10% for advertising; 25% or more for delivery). Among other things, given its inordinate power and essential role in package delivery, the question posed is why Amazon is not integrated into a publicly-owned utility, that is, a modernized, socially accountable post-office.

Furthermore, Amazon also benefits from highly favourable access to finance. Its privileged position allows it to generate essentially interest-free loans through the cash cycle as it gets paid immediately for orders but pays suppliers only after a lag. And investors are happy to buy Amazon stock without demanding dividends because they expect the stock to steadily and rapidly rise.

The 1.6 million packages Amazon delivers daily are also cultural packages acting to narrow society to private consumers desperate to get their goods ‘Now!’ This inherent consumerist bias in capitalism tends to serve as a compensation for the many things wrong in people’s lives, as it blanks out people as workers and undervalues social consumption (from universal healthcare to free education, from free public transportation to shared physical and cultural spaces).

Above all, the success of Amazon is inseparable from its relationship to its workforce. Amazon has made Jeff Bezos the third wealthiest man in the world (now retired with an estimated net worth of $196-billion), but somehow it ‘cannot’ pay its workers even the average US wage (currently some 50% above the Amazon standard).

And for all its technology and smarts, this global leader refuses to provide a safe workplace. While Amazon proudly proclaims that “we are committed to and invested in safety,” its drive for healthy profits comes at the expense of its concern for healthy workers. Amazon’s injury rate is double the rest of the warehouse sector, which itself has higher injury rates than the overall economy. A window on Amazon’s underlying sentiments toward safety is revealed in how it provides free pain killers through dispensing machines scattered throughout its warehouses.

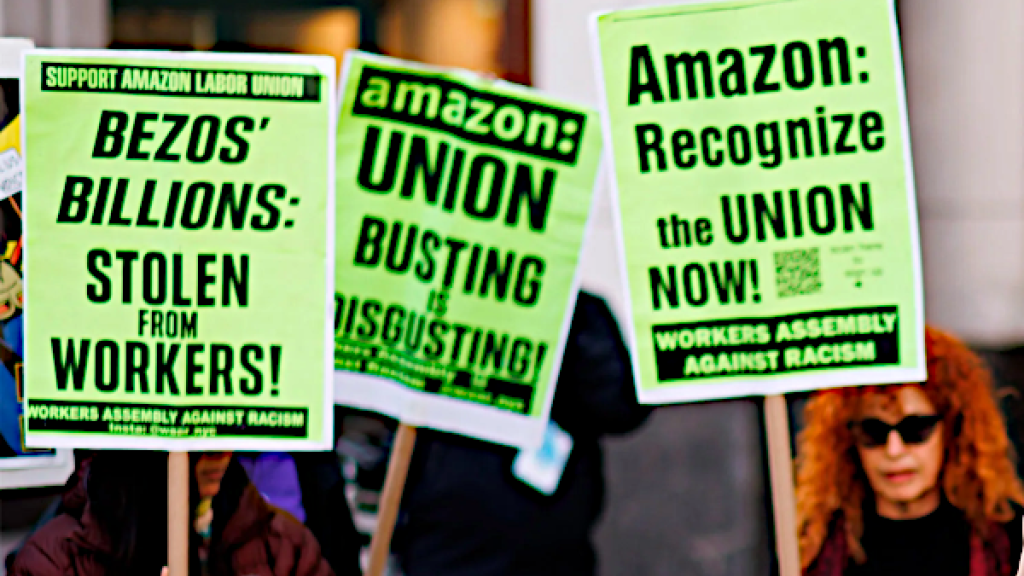

Amazon’s attitude to its workforce innately extends to its contempt for any degree of worker democracy. For Amazon, ‘democracy’ means voting with your dollars on what to buy, and ‘freedom’ means unregulated markets for business. Denying its workforce the right to choose, without interference, by whom and how they should be represented is for Amazon not a patronizing and arrogant affront to workers’ democracy and freedoms, but business as usual. Over and above its workplace intimidation, Amazon spends millions – at last count over $14-million to consultants alone – on undermining unionization from acting as a check on its power.

Most recently, Amazon’s contempt for democracy went so far as to file a suit to make America’s National Labour Relations Act unconstitutional. The Act’s preamble was too much for Amazon’s perspective on freedom, introducing as the Act does, an institution that “protects workplace democracy by providing employees… the fundamental right to seek better working conditions and designation of representation without fear of retaliation.”

Yes, people nevertheless choose to work at Amazon, unionized or not. But that speaks to the limited choices in a society in which capitalist profits overwhelm other priorities (which, of course, is why we call such a society ‘capitalism’).

Can Amazon be tamed?

Highlighting Amazon’s power can lead to a paralyzing sense of its invincibility. If Amazon is an all-powerful monopoly and faces no competition, worker disruptions could be waited out. But if Amazon faces stiff competition, then worker actions matter a great deal since their actions can threaten Amazon’s reputation for dependability and immediacy, thereby threatening sales. Amazon’s high on-going cost structures make this especially significant. The combination of high fixed costs and imperilled revenue from a decline in market share translates directly into a decline in profits.

Those high costs are primarily the consequence of the quantity and variety of products Amazon must have readily available, which necessitates massive investments in warehouses. Moreover, no method of delivery is more expensive than getting individual packages to individual homes. And Amazon’s logistical systems that coordinate the daily arrival and distribution of millions of products from around the world require the highest levels of on-going research and investment in software and computer hardware.

The concentration of capital represented by Amazon does, of course, include aspects of ‘monopoly power’. But concentration doesn’t necessarily bring immunity from competition. For one, the larger the capital invested, the more essential it is to expand your market to justify the large investments. For another, powerful corporations must constantly regenerate its competitive status if it is to retain its market advantages.

The development of capitalism has consequently intensified, not diminished, competition. The emergence of national markets undermined regional monopolies. Globalization internationalizes competition. Financialization – by virtue of its relative ease in moving to more favourable projects – pushes companies and states to compete for privileged access to funds by proving their commitment to prioritizing capitalist, not social, goals.

In the retail sector, the aggressiveness of competition is made clear in the sector’s notoriously small profit margins. Amazon continually battles other retailers for its share of the market and especially its share of the overall profits generated. Competition also pits Amazon against the suppliers of the goods it sells: the shippers, rail companies, and the port operators that bring the goods to its warehouses and the truckers and posties who later move the goods to consumers. There is, of course, competition from companies trying to keep up with or make inroads into Amazon (Walmart, Target, Best Buy) and from new entrants into e-shopping like Shopify.

Notably, Amazon also competes with other alleged ‘monopolies’: Google and Facebook over the advertising dollar, Microsoft over the cloud, and with new and old companies over AI.

It may seem that these pressures are cushioned by Amazon’s privileged access to finance and ability to squeeze third-party sellers through its privatized ‘toll road’. But these advantages are not the core of its power, which is derived from its capacity to deliver what people want fast. It’s the organized capacity of workers to ‘reverse-engineer’ the workplace so as to turn Amazon’s core strength into Amazon’s greatest vulnerability that is the greatest threat to Amazon.

Retaining its sacred reputation for dependability pushes Amazon to double down on cost controls, rigid monitoring of workers, and a determination to block workers from any agency over their labour power. And yet, though this might defeat a particular worker uprising, it may also intensify sympathy for unionization. However, while the potential for unionization persists at Amazon, the traditional union approach – winning a certification vote, negotiating an agreement, and striking if necessary – faces special, perhaps insurmountable, limits. This brings us to the question of worker strategies.

Part III: Strategy

Worker power and Amazon

For the young socialists who joined the Amazon workforce to help organize it or contributed as external organizers, the starting point was the permanence of class struggle under capitalism. The signing of collective agreements does not end this battle, but rather creates an asymmetric ‘peace’. The corporate side makes some concessions but retains the right to manage, reorganize work, and raise production standards during the 3 to 5 year life of the agreement; the union may gain a few rights but basically goes along with foreclosing workforce-led disruptions. As one organizer put it, this leaves workers facing a period of class struggle in which only one side is fighting.

The counter is a model of organizing that is driven by the triumvirate of: a class perspective focused on the workplace; a commitment to both comprehensive and deep organizing; and a capacity to disrupt Amazon in an on-going and unpredictable way. This radical understanding has substantively raised the level of strategic debate among socialist organizers and led to the specific determination to unionize Amazon as a step in transforming unions and building the base to transform society. What follows is a discussion of responses, informed by this orientation, to key issues that have surfaced in the course of the drive to organize Amazon.

This discussion, it needs to be emphasized, is not intended to be definitive but to stimulate debate and re-evaluation as Amazon organizing proceeds.

Strategic goal

The goal is building worker power at Amazon. Certification – getting sufficient number of workers to sign secret cards calling for a vote on unionization – can certainly play a role in unifying and sustaining workers in the drive to build workplace power. Its achievement could also offer some protection from the firing of activists and provide funding through a dues check-off for all workers. But certification in itself – ‘organizing light’ – must not be confused with the building of lasting workplace power.

The short history of organizing at Amazon speaks to this danger. Certifications were either lost by a traditional approach (RWDSU in Bessemer, Alabama) or were successful but lacked the capacity to respond when Amazon refused to recognize the union (ALU on Staten Island). In Chicago, a militant minority dismissed certification all together, but without any alternative model to unite and sustain large numbers of workers, it too faded.

Leverage

The socialist organizers well understood that the key to union renewal is inseparable from developing the workplace capacity to challenge management control with decentralized, but ultimately coordinated, resistance. Full-blown strikes aren’t excluded, but the worker arsenal requires the whole gamut of disruptions: slowdowns, sit-downs, key departmental walkouts, health and safety refusals, resistance to raising production rates, etc.

Traditional strikes are especially limited at Amazon because of the excess capacity built into its operations and Amazon’s logistical capacity to reroute packages. In each region, Amazon has clusters of facilities that do similar work and this homogeneity makes shifting production possible. Moreover, against the general trend to reducing excess inventories and excess capacity (‘lean production’), Amazon’s facilities run on permanent excess capacity as evidenced by Amazon’s ability to increase its delivery of packages on Prime Days by some 50% or more.

The organizational unit

The foundation for building worker’s countervailing power vis-à-vis management demands organizers trained to maximize participation in each department and across social groups (significant ethnic blocs are common in many Amazon facilities), leading to what Jane McAlevey references as workplace ‘super-majorities’. This is not just a numbers game but a matter of the depth of participation, which means appreciating the need to develop the capacities and confidence of workers to actually participate. This further supports not only winning a union but, through such participation, the building of a democratic union.

This prioritizing of the collective capacity to disrupt/control production through what is essentially guerrilla war in the workplace contrasts, in spirit and practice, with establishing committees to gather certification signatures with hopes to build power later. At Amazon, ‘later’ may not come if Amazon refuses to acknowledge certification (or, if certification comes too quickly, it may hide the unit’s lack of readiness). This is, again, not a matter of rejecting certification as a tactic on which to build but to place certification in the context of its subordination to the readiness to act like a union.

Still, one facility alone, even with such creative disruptive capacities, is unlikely (key air-hubs aside) to be adequate to Amazon’s own creative abilities to get around isolated disruptions. A base in more than one facility will be necessary.

Regional vs national sites of organizing

It may seem that Amazon must be organized at a scale that matches or comes close to matching Amazon’s own national/international scale. Ultimately, that would, of course, be welcome. But organizing is always local, and in the case of Amazon, its own operating model provides a tactical opportunity for a regional focus. That Amazon is structured around regional clusters of extended urban areas allows for acting as a union within these regional spaces and demonstrating the relevance of a union well before national organizing goals are achieved.

Framing the critical space of organizing to be the national level rather than regional clusters has three particular implications. First, it immediately excludes independent unions. They simply don’t have the resources to take this on. Therefore the logic from the start favours a turn to a union like the Teamsters with their resources and national presence.

Second, the focus on only taking on Amazon after you have a critical mass of high-volume warehouses across the country, and then striking on key dates (Amazon’s super-busy Prime Days), seems to return us to the traditional union approach. It incorporates a bias to focus on federating regional local chapters before the essential deep drilling within each chapter has been achieved. To argue that we need to do both still leaves open the balance and timing between them.

Third, if the argument is that you need a large national presence to carry out a traditional strike, then the unevenness of organizing between regions will imply a good many chapters left waiting for years for that strike; such a limbo is death to organizing. In contrast, a model based on regions and disruption within regions avoids indefinite waiting. It allows for acting as a union regionally, while others catch-up and then organically unite in a federation of strong semi-autonomous chapters.

The counter to a regional focus is that, if Amazon makes substantive concessions in one region, this will surely spread to other regions. Amazon would therefore measure the costs of any regional concession against their multiplication far beyond that region and resist all the harder. A national or near-national strike of key facilities is allegedly, therefore, the only option.

This is not to be casually dismissed. But the limits to the nationally-based option suggest another alternative: disruptions in particular regions stimulating, or operating parallel to, disruptions in multiple regions. To a degree equal to or greater than a national test of strength, this may bring home the strategic message that Amazon cannot operate disruption-free without concessions to workers.

Those first gains for workers may be modest in the scheme of things, but they can build the base for larger, national-level challenges to come, like greater choices on shift hours, improved health and safety, longer breaks, taking productivity gains in the form of reduced work hours, more humane production rates that force Amazon to meet its consumer commitments through hiring more workers rather than speed-up, etc.

Spatial site of struggle within regions

The issue of scale is also a tactical question within each regional chapter. Outside of the disruptive power of a key organized air-hub (or two) flying packages across the US for same or next day delivery, having organized more than a couple of facilities in a major region will likely be essential to force Amazon into bargaining.

The critical number of common facilities needed in a region is indeterminate in the abstract. A small number of either sortable facilities (small-medium packages) or non-sortables (large packages) may be enough to significantly impose costs on Amazon. Research can be suggestive, but the exact number of facilities needed is likely to emerge only in the course of actually testing Amazon.

Functional point of struggle

The most strategically positioned workers are the white-collar techies in Amazon Web Services (AWS). But though they have expressed progressive positions on race, gender, immigration, and the environment, they haven’t demonstrated interest in unionization even in the face of recent corporate layoffs. The most we can likely expect from this layer of workers is that, as the blue-collar workers win some workplace power, their more highly skilled co-workers might be moved to joint the fight and raise their own voices, especially as union-protected whistle-blowers.

The key debate is consequently whether organizing should prioritize the large fulfilment centres (FCs) or the delivery stations and their drivers. Both sides in this debate recognize that the large numbers of blue-collar workers at the FCs must ultimately be organized to bring the maximum numbers of workers into the labour movement and to have a dramatic impact on the strategies of labour. Both sides likewise agree that the more links in the chain that are unionized, the stronger the union will be. The controversy is over which to concentrate on first.

The argument for the delivery stations is that they would be easier to unionize because of their smaller size, and that they could serve as a foothold for moving on to the larger prize of the fulfillment centres. Especially important, delivery stations are considered ‘chokeholds’: close the delivery stations and nothing gets to the doorsteps.

The challenge begins with it not being obvious that organizing the drivers would spread to the rest of the workers in the stations, or that this would be decisive in winning the FCs over. So, if the FC’s are the ultimate goal, why not start there? As for the delivery stations representing critical chokeholds, this can slip into a variation of the traditional union strategy of periodic formal collective bargaining with a militant edge, instead of the distinct leverage being a widespread capacity to disrupt if and when necessary.

Moreover, since the work of a group of drivers can readily be re-routed (unless their home delivery station is uniquely located), subcontracted drivers can be shifted to other hungry entrepreneurs. Multiple stations would consequently have to be unionized to be effective, reducing the ‘ease of unionizing’ argument. And though closing and replacing a delivery station if unionization is at stake may be disruptive, Amazon generally operates with an excess number of stations and closing a troublesome one remains far easier than closing a mammoth warehouse given the relative size of the investment involved.

The entry of the Teamsters: A game changer?

The Teamsters have had Amazon in their sights for some time, but their recent interventions by way of a newly formed Amazon Division are clearly a game-changer. What reinforced the Teamsters’ prominence is that the organizing project of the socialist activists is inherently a slow build for practical reasons (it’s hard and Amazon makes it harder), contextual reasons (though the campus protests over Gaza are signalling a new youth radicalization, this is not yet a moment when explosive rebellions are ‘in the air’ the way they were in the 60s), and because the very pace of the model being applied – the methodical build-up of capacities – simply takes time.

These factors took a toll and worked to the advantage of the Teamsters. What the Teamsters offer is the material (and psychological) benefits of an established institution, with experience in logistics, having workers’ backs. The Teamsters have the resources to pay for the essentials of full-time and part-time organizers, agitational literature. meeting spaces, and lawyer fees at a moment when the collective strength for carrying out direct action to block firings or suspensions does not yet generally exist. The Teamsters can also, because of their resources, make a credible-sounding promise to get things done quicker, something that would understandably appeal to many workers not yet won over to a strategy with an indefinite timeline.

These realities touched a nerve with some supporters of an independent union facing the demoralization of no ready examples to confirm the merits of slow building. An example of this dynamic occurred at Amazon’s Kentucky air-hub, perhaps Amazon’s most important North American facility. The organizers were committed to building an independent union and had impressive results at first, quickly getting some 1300 workers signed up out of a workforce of some 4300 (30%). At that point, however, the cards slowed down in the face of the aggressive reaction of Amazon and the not-uncommon occurrence of ebbs in organizing drives. The former antagonism to the Teamsters mellowed, and the independent organizers now seem to be in unionizing talks with the Teamsters.

The Teamsters’ new Amazon Division has so far had the autonomy and resources needed to overcome the barriers faced. As with the CIO in the 1930s, the Amazon Division welcomed effective organizers no matter their political background. And the division didn’t rush to quick certs but emphasized, as the independent socialists were doing, the systematic training of cadre who could carry out deep organizing and build super-majorities. The Division soon won over and hired some of the best organizers in key centres such as San Bernardino, Philadelphia, New York, and Kentucky. This has reinforced a general sense across regions that going to the Teamsters is now a matter of ‘when’, not ‘if’.

Currently, two particular concerns stand out. Is the Teamster’s prioritizing of the delivery stations – natural enough given their drivers’ base – the right road toward organizing Amazon? (The Amazon Division seems to be developing some flexibility on this of late, moving to include FCs in their plan). And is there a contradiction between the Amazon Division’s openness to a new approach and trying to do so within a union that remains, overall, a still traditional union?

A test of this potential contradiction revolves around the weight given to legal changes and the political cycle. The Teamsters have been fighting to redefine the subcontracted delivery drivers as de facto Amazon workers (which they, in fact, are). As well, a new National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruling asserts that if a majority of the workers sign up for the union, and on the way to a vote the corporation is ruled to have committed an unfair labour practice, the NLRB can impose a collective agreement. With the US election coming up and nervousness about a Trump victory reversing these legal and administrative gains, pressures may emerge in the union to speed up certifications to beat the short-term timeframe.

The problem isn’t that concern with legalities and political developments is a sin, but that – as with all tactics – the danger of the tactic driving the strategy of building worker power. If, for example, organizing timetables are adjusted to accommodate the political cycle, this might offer some short-term successes. But unless the goal of building the base is an absolute, even a collective agreement at Amazon can be undermined during the life of the agreement or in the conflict over the subsequent agreement.

If positive results are slow in coming while costs escalate, the risk of the Teamster leadership pushing the Amazon drive into traditional channels or even prematurely abandoning the drive cannot be disregarded. To date, however, the Amazon Division seems to have the autonomy to stick to its organizing plan and timetable.

For socialists a further set of questions arises. If their future lies inside the Teamsters, how will they operate within the Teamsters? What lessons can be taken from the experience of the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), once a courageous and effective oppositional force for democracy but now essentially the integrated militant edge of the Teamsters (characterized by some as ‘militant business unionism’)? Could socialists and a revived TDU move the Teamsters from being a primarily driver-based union in its emphasis, to a warehouse/logistics union?

Could the socialists bring ‘class’ into the analysis as a practical matter rather than just rhetorically? That is, can socialist organizers convince that incorporating the salience of class can make unions more effective? As well, since any battle demands understanding your enemy, could a left inside the Teamsters move the workforce to see capitalism – and not just their employer – as the ultimate impediment to a more secure, fuller life? (There is, as well, the disturbing question of what the fall-out might be if even the Teamsters failed at Amazon.)

In addressing the role of the Teamsters, the Canadian situation is distinct. While US Teamsters have, among established unions, emerged as ‘the Amazon union’, this is not the case in Canada. In Canada, the Teamsters are smaller and weaker than in the US, and there are now two-three other unions, none unambiguously in the lead, joining the Teamsters to test the waters for an Amazon drive: the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW, passive of late), Unifor (formerly the CAW) in BC, and the CSN (a federation of unions in Quebec).

This leaves open the possibility in Canada – undoubtedly a long shot – of the labour movement as a whole or a coalition of unions supporting a centralized fund to support an independent union, give it access to their own union members to convince them of the fundamental centrality of Amazon to overall union renewal, gather contacts these workers have through family connections or friendships to Amazon workers, and even recruit people taking jobs in Amazon with the intention of building a union.

This would, crucially, also lay the base as the struggle advances for taming Amazon through coordinated actions of support from longshoremen, railway workers, cargo package handlers, truckers, posties, and so on. Ultimately, the Amazon workers would decide whether to remain independent or choose one of the contending unions (an incentive for wavering unions to show concrete solidarity in order to ‘stay in the game’).

Recent developments, however, point to specific unions presiding over or at least greatly influencing the organizing of Amazon in Canada. The CSN recently won the first certification in Canada at a sort centre (200 workers) and Unifor seems to be on the verge of filing for certification at two FCs (perhaps 2000 workers combined). Note that in Quebec and BC automatic certification requires exceeding only 50% and 55% respectively. As well, against Amazon’s determination to ignore union certifications, labour boards in both provinces can impose a first contract if the union is certified but the two parties don’t reach a collective agreement.

Conclusion

The Amazon organizing model discussed here poses three tests for labour and the left. Can traditional unionism bring power to Amazon workers and if not, what kind of trade unionism might? Can the struggle at Amazon contribute to transforming the labour movement? And are unions – the primary economic institution of the working class – adequate to confronting modern capitalism or do they need to be supplemented by other forms of working-class organization?

The challenge for unions is not just winning certification, but building substantive worker power. At Amazon, the odds of doing so through traditional means are not great – even with the best intentions and the greatest commitment of resources. Most promising is the orientation of the new socialist organizers. Namely, while respecting the labour movement’s trajectory of emphasizing improved compensation for the crushing conditions workers face, emphasize the urgency of addressing the improvement of those conditions themselves. Link this turn to the workplace to the necessity of building a capacity to disrupt on an on-going basis, not just periodic strikes. And above all, build the depth of the collective workers, not just their numbers. This further demands developing the best possible trained leaders in the workplace and organizing externally to develop the fullest support from the union movement as a whole.

D. Taylor, the recently retired president of UNITE HERE, goes a step further in emphasizing the limits of a single union taking on Amazon even with ‘support’ from other unions. Organizing Amazon, he argues, will “take not one union but a powerful coalition of unions, a force like the CIO in the 1930s.” Taylor’s class sentiment is to be valued, but the call for a crusade undertaken by existing unions underestimates the impact of labour’s long defeat and the prior transformations within unions necessary to pull this off.

Taylor’s referencing the CIO highlights the historical differences that block his proposal. In spite of all the inequalities, irrationalities, and suffering in the US today, the crisis is not yet on the scale of the Great Depression. At that moment, one worker in four was unemployed, on-going community battles over homelessness were common, and working people were on the march. Moreover, the craft-dominated unions at the time weren’t just uninterested in, but actively opposed to, organizing the unskilled ‘riffraff’. This pointed to the necessity of considering new unions. Today’s unions, in contrast, are anxious to bring workers of any status into the movement, but have a checkered record in their capacity to do so. There was also a further factor in the success of the early CIO: a Communist Party that trained and sent committed workers into workplaces to organize, backed by the party’s strategic oversight. Nothing comparable is in play today.

The emergence of the Teamsters as the agency that will enter the ring with Amazon, effectively forecloses, at least in the US, the kind of coalition of unions that Taylor raises. Moreover, there is little ground for expecting general union renewal through a dynamic solely internal to unions. Taking on the Amazon Goliath may not succeed without the equivalent of a party or proto-party with bases in unions, across unions, and in class-based social movements. Without such an institutionalized working class agency it will be extremely difficult to push the Teamsters in a positive direction, coordinate socialist cadres operating within the Teamsters, and focus on transforming unions beyond the Teamsters so a cross-union crusade is not just a talking point.

More generally, the prime role of a socialist party in this current moment is to counter the ways that capitalism shapes the working class with a socialist-leaning remaking of workers into a collective social force with the understandings, vision, strategic and organizational capacities, and the ambition and confidence to take on not just the bosses but also the capitalist system.

Finally, we must not forget that even with the best unions doing everything right, workers return after each struggle to a workplace in which their employers still determine the hiring and laying-off of workers, the basics of their combination into social labour, how workers’ skills are developed (or narrowed), how and where profits are invested, and the products and services produced. These limits are not a denigration of what workers can achieve in terms of respect from and limits on management, but a reminder to see union gains not as end points but as building blocks, steps to a transformed society and to transformed working-class lives.

Sam Gindin was research director of the Canadian Auto Workers from 1974–2000. He is co-author (with Leo Panitch) of The Making of Global Capitalism (Verso), and co-author with Leo Panitch and Steve Maher of The Socialist Challenge Today, the expanded and updated American edition (Haymarket).