Capital, power and war: The crisis of Russia’s peripheral accumulation regime

An event organised by the Left Political Prisoners Support Fund and Freedom Zone in support of Russian political prisoners, in Belgrade this July, gave Ilya Matveev and me a rare opportunity to continue — this time face to face — our ongoing discussion about the relative weight of economic and political (or ideological) factors in contemporary Russian politics, particularly in relation to the launch and continuation of the war in Ukraine. Our earlier exchange (see Matveev’s original argument and my response) was published on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal last year. This latest discussion helped bring our positions into closer alignment.

Neither of us denies the importance of either economics or ideology in shaping state policy; and both of us agree that political outcomes emerge from the complex and dynamic interaction between the two. As we concluded, the key lies in understanding the balance between structural economic determinants and the more contingent role of political decisions. Economics sets the parameters and long-term trends; politics intervenes in specific conjunctures, tipping the scales toward one outcome or another.

In his essay “Once Again on the Trade Unions, the Current Situation and the Mistakes of Trotsky and Bukharin,” Vladimir Lenin presents what may appear to be two contradictory claims: (a) politics is a concentrated expression of economics, and (b) politics must take precedence over economics — an assertion he calls “an ABC of Marxism.” Far from a contradiction, this is a dialectical formulation.

In general, economic relations define the limits and terrain within which politics operates. Yet under certain historical conditions — especially during revolutionary ruptures — politics becomes the vehicle through which those economic relations are transformed. Subjective factors such as class consciousness, political organisation and leadership can gain decisive importance. In this sense, politics can “lead” economics by organising class forces in ways that alter the very economic structures from which they emerged.

This dialectical reversal — where the superstructure acquires relative autonomy and, in specific conjunctures, reshapes the base — is a recurring theme in Marxist thought. Lenin’s position echoes Karl Marx’s analysis of the Paris Commune, a political event whose significance lay in its potential to transform the economic foundations of society. As Marx wrote in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, people make their own history, but not under conditions of their own choosing — a formulation that captures the unity of structural constraints and political agency.

While acknowledging the important role of politics and ideology, it remains crucial to analyse how Russia’s model of capitalist accumulation created the structural conditions — the framework — within which subsequent political decisions were made. That is the focus of this article.

What kind of capitalism is Russia?

The accumulation regime that dominated Russia from the early 2000s until roughly 2013-14 — before slipping into stagnation — is best understood through the lens of Regulation theory, which emphasises the organic interdependence between economic structures, institutional forms and modes of reproduction. According to this approach, capitalism is not a single, uniform model but a historically specific configuration of accumulation and regulation. Each regime is defined by a coherent (if often temporary) alignment between how profits are generated (the accumulation regime) and how social and institutional structures support or contain this process (the mode of regulation).

Drawing on Robert Boyer’s typology of post-socialist accumulation regimes, Russia — along with Ukraine — fits squarely within the category of oligarchic or rentier capitalism. In this model, the economy is heavily dependent on raw material exports, while capital accumulation is deeply entangled with political power and rent distribution. Unlike developmental or export-oriented regimes, where capital is reinvested into expanding production, the Russian model channels surplus rent toward elite consumption, asset protection abroad and politically-mediated redistribution.

This model also bears the deeper structural imprint of peripheral capitalism, as theorised by Boris Kagarlitsky in Empire of the Periphery and Restoration in Russia: Why Capitalism Failed. Kagarlitsky argues that Russia’s capitalist development after the Soviet collapse was not oriented toward internal industrial transformation or the creation of a self-sustaining national economy. Rather, it was shaped by the requirements of the global capitalist centre, especially in Western Europe and North America.

Russia emerged as a provider of cheap raw materials and a destination for capital outflows into real estate and financial safe havens. Its integration into the world-system was therefore subordinate, driven by external demand and the reproduction of global inequalities rather than domestic developmental needs. In this sense, Russia’s position more closely resembles that of a peripheral capitalist formation, structurally dependent on rent extraction and external capital circuits.

This regime relied on the extraction of resource rents — primarily from oil, gas, and metals — that became the foundation of foreign exchange earnings, fiscal revenues, and elite enrichment. But accumulation followed a political, not competitive, logic. Access to rents was governed by proximity to the state. Contracts, licenses and control over public assets — not entrepreneurial innovation — determined wealth and influence. In this sense, Russian capitalism conforms to Max Weber’s notion of political capitalism, in which the means of enrichment are shaped by privileged access to political power rather than market dynamics.

Branko Milanović has argued that this kind of capitalism thrives not through production but rent-seeking. Volodymyr Ishchenko notes in the Ukrainian context (which mirrors the Russian experience), the boundaries between business and politics are porous: capitalist accumulation depends less on autonomous institutions and more on informal networks, clientelist ties, and shifting elite coalitions. Kagarlitsky similarly describes Russian capitalism as a system in which class power is exercised through a fusion of economic and administrative control, with state elites doubling as capitalists.

Why did Russia’s capitalism run out of steam?

Despite its apparent stability during the commodity boom years, Russia’s accumulation regime began to falter by the mid-2010s. Its decline was driven by a set of interrelated internal and external contradictions that gradually eroded its capacity to reproduce capital on an expanded scale.

The first and most immediate sign of strain was a profitability crisis. While the natural resource sectors continued to yield substantial rents, much of the rest of the economy — particularly manufacturing and services — faced stagnating productivity and falling returns. Marx observed that capital must expand or perish. In Russia’s case, the expansionary impulse was not exhausted due to a shortage of capital, but rather because the regime failed to generate sustained internal dynamism.

This crisis of profitability is evident in key financial return indicators (Figure 1). Both return on assets (ROA) and return on sales (ROS) declined steadily from the mid-2000s until the mid-2010s. ROS, which had hovered around 13–14% in the early 2000s, dropped to just over 8% by 2015. ROA fell even more dramatically, from a peak above 12% in 2006 to just 3% in 2015. This prolonged decline reflected not only the structural limits of rent-based accumulation, but also the mounting constraints imposed by Russia’s deteriorating external environment, particularly following the 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Yet starting around 2015–2016 — precisely as Russia began to “flex its muscles” geopolitically — profitability indicators began to recover. This resurgence was not the result of productive diversification or reinvestment, but stemmed from a combination of import substitution, state-directed spending and militarisation. The spike in ROS in about 2021–22 signals a wartime reprieve, driven by rising commodity prices and emergency fiscal measures. However, the recovery was uneven: ROA remained well below its pre-crisis peaks, suggesting that profitability in Russia is still dependent on external rents and state interventions, rather than structural competitiveness.

Closely tied to the profitability dynamic was the question of domestic investment. Russian capitalists have long preferred to safeguard their wealth abroad, and this behaviour persisted even during the boom years. Structural barriers — including weak property rights, politicised courts, elite factionalism and the chronic absence of institutional trust — made Russia a high-risk environment for long-term reinvestment. Even when capital was available, flight remained the rational option.

The consequences of capital aversion are starkly reflected in the growth pattern of investment in fixed assets between 2011–20. After reaching more than 20% in 2012, the growth rate steadily declined, falling to just 5.5% by 2020. This sustained slowdown mirrored the erosion of profitability, with both trends bottoming out around the same time.

The close alignment of these trajectories reinforces the structural link between profitability and investment: from Marxian, Keynesian and Kaleckian perspectives alike, falling profit rates provoke an “investment strike,” as capitalists respond by scaling back expansion and postponing capital commitments. Empirically, this is supported by a moderate to strong correlation (r between 0.66 and 0.67) that is statistically significant at the 1% level between investment growth and both ROA and ROS, confirming that declining returns materially shaped investment behaviour in this period.

After 2021, a dramatic — but involuntary — reversal occurred. The annual growth of investment in fixed assets surged to more than 22% in 2022 and remained elevated in the years that followed. This sharp reactivation was not driven by renewed investor confidence but by a fundamentally altered operating environment. Capital controls, international sanctions and Russia’s financial decoupling from the West restricted traditional avenues for capital flight. Simultaneously, the state expanded military and infrastructure procurement and imposed sweeping import substitution mandates. Wartime fiscal expansion boosted returns in key protected sectors, reigniting investment not through incentives, but through necessity.

Yet, this rebound should not be misread as a sign of systemic strength. Capital remained within Russia not due to an improved investment climate, but because escape routes were closed. What appears as investment-led recovery is better understood as the redirection of surplus under siege: coerced, managed and politically orchestrated, rather than market-driven or strategically planned.

This dynamic underscores a broader analytical point: in peripheral political capitalism, accumulation is shaped less by market logic than by political constraints and structural dependencies. The correlation between profitability and investment in Russia is real — but it is mediated through a framework of elite behaviour, capital controls and geopolitical isolation.

In addition to these internal contradictions, the post-2014 rupture also severed key external linkages. Russia’s integration into global capitalism had always been subordinate: petrodollars were recycled into Western financial markets, while the domestic economy remained dependent on imported technology, components, and credit. The sanctions regime drastically curtailed these flows, undermining the very architecture of accumulation without offering a viable alternative.

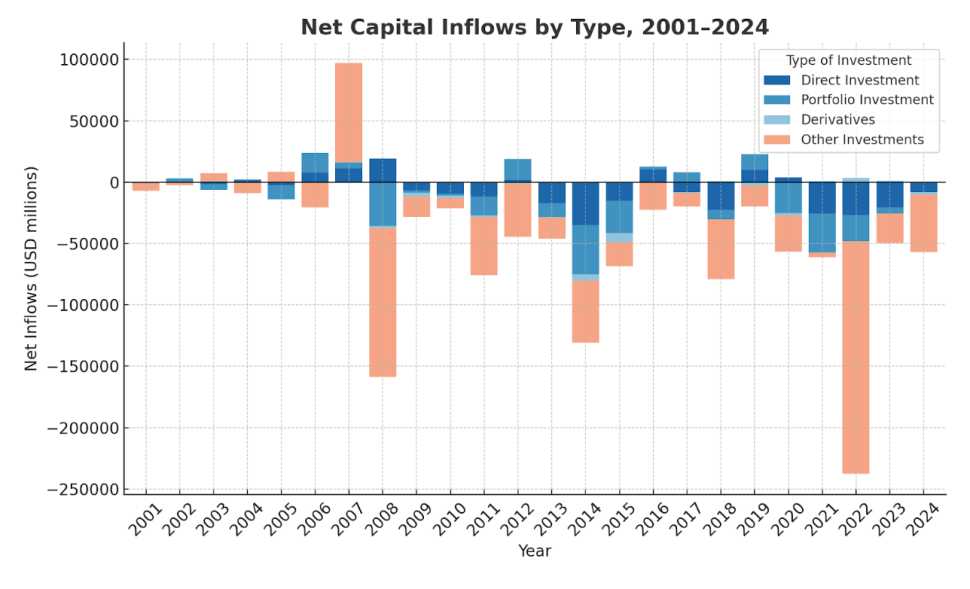

Capital flight remained a defining feature of the Russian accumulation regime even after 2014, despite tightening sanctions and capital controls. As the chart above shows, net capital outflows not only persisted but, in many cases, intensified, particularly in the form of other investments — a broad residual category that includes trade credits, intercompany loans, and bank deposits. These channels are often used for discreet or informal capital flight, especially when formal mechanisms are restricted. The share of other investments has on average remained high throughout the period, accounting in some years for up to 80% of all capital flows.

The huge capital outflow recorded in 2022 — driven by geopolitical uncertainty, emergency withdrawals and systemic disruptions in cross-border financial relationships — confirms the regime’s structural dependence on external financial circuits. However, the dynamics in 2023–24 suggest a partial reversal: outflows from other investments decreased significantly, and similar declines were observed across other categories, indicating a temporary containment of capital flight. Still, this shift should be interpreted cautiously — as a response to restricted exit routes and wartime controls, not as evidence of improved investor confidence or a structurally sound accumulation environment.

Finally, the end of the global commodity super-cycle in the mid-2010s eroded the fiscal foundation of the rentier model. Falling prices undercut both budget revenues and external surpluses. The temporary post-2022 rebound — driven by war-related price spikes and emergency spending — has not resolved these long-term vulnerabilities. If anything, it has exposed the fragility of a model that remains dependent on rents, repression, and reactive policy interventions.

Russia’s war-driven accumulation regime

The Russian economy has undergone a profound transformation since the escalation of the war in Ukraine in 2022. While the outlines of this transformation could already be discerned in the aftermath of the 2014 annexation of Crimea, it is only in the wake of the full-scale invasion and the unprecedented scale of Western sanctions that a new accumulation regime has coherently taken shape.

This section builds on the previous discussion of post-2014 and post-2022 trends — especially the decline of foreign direct investment, the reversal of net primary income flows and the reorientation of trade patterns — to outline the logic of the emergent model of capital accumulation. As I argue in my LINKS article “Russia’s Delinking from the West: The Great Equaliser,” this model represents a rupture from the previous globalist framework, centred instead on war-driven expansion and domestic reproduction.

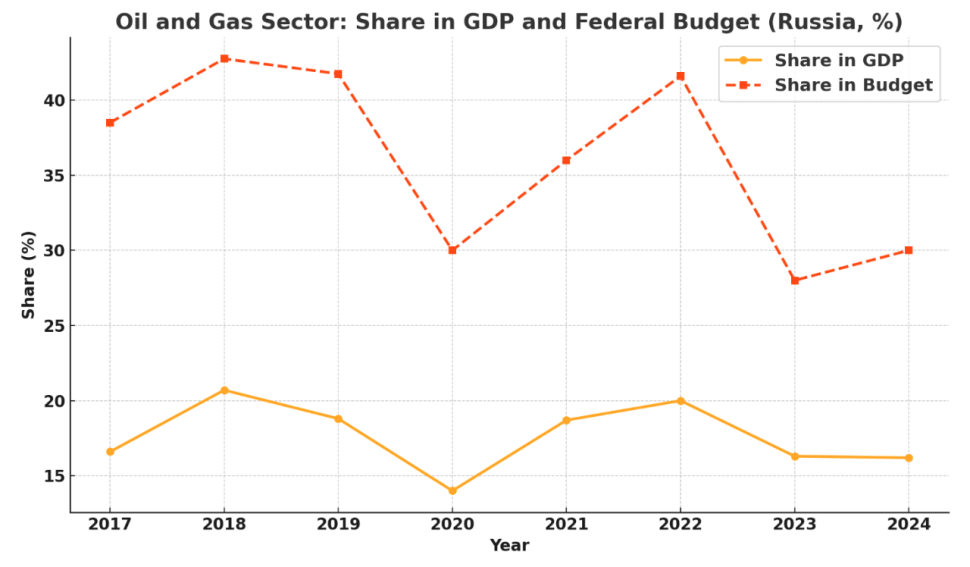

Yet how profound is this transformation in structural terms? Despite the regime’s pivot toward military-industrial expansion and sanctioned self-reliance, the basic logic of peripheral capitalist accumulation — rooted in natural resource exports, particularly hydrocarbons — remains intact (Figure 4). After the COVID-induced contraction in 2020, when the oil and gas sector’s share in GDP dropped to 14%, there was a sharp recovery, peaking in 2022 at 20%, as global energy markets responded to the war with panic-driven price spikes. By 2023 and 2024, the share returned to around 16%, nearly identical to its 2017 level. This cyclical pattern suggests continuity rather than rupture: the export sector remains central to the Russian economy, and no genuine diversification or structural upgrading has occurred.

A similar pattern holds for the share of oil and gas revenues in the federal budget. Although this share declined in 2023 and 2024 — to 28% and 30% respectively, down from 41.6% in 2022 — the drop is not unprecedented. Comparable levels were observed during the 2020–21 period, reflecting earlier price and demand shocks. Whether the recent decline signals a sustained reduction in fiscal dependency or merely another phase in the commodity cycle remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that the state budget remains structurally dependent on hydrocarbon rents, with oil and gas revenues consistently contributing between one-quarter and nearly half of federal income across the past decade.

The so-called “new” accumulation regime may therefore reflect a reorganisation of rent distribution and elite composition, but it does not alter the extractive foundation on which Russian capitalism rests.

Since 2022, Russia’s accumulation regime has become increasingly reliant on what could be termed “military Keynesianism,” a state-led effort to stimulate economic growth through huge defense spending, infrastructure development and industrial policy directed from above — the features analysed by Ishchenko, Matveev and Oleg Zhuravlev. The war effort and Western sanctions have largely displaced foreign investment and external trade as key sources of accumulation, replacing them with state demand, procurement contracts, and strategic subsidies.

Import substitution has intensified, not merely as a policy slogan but as an enforced reality. With Russia partially delinked from Western markets and supply chains, domestic industries have stepped in to fill the void, often under the shelter of high tariffs, financial controls and generous state support. These industries — ranging from agro-processing and logistics to basic manufacturing and chemicals — are not exposed to global competition; instead, they are protected and stabilised by predictable state contracts and informal rent-sharing arrangements.

This transformation has created new patterns of profitability, as illustrated by the chart tracking the evolution of profitability over time, particularly the rising trend since 2014 (Figure 1). Capitalists positioned in sectors aligned with state priorities — especially construction firms, arms manufacturers, and logistics companies — have seen profits rise even amid macroeconomic uncertainty.

For this cohort, the war has become not a disruption but a condition of accumulation. Any form of peace agreement that reopens Russia to global competition and winds down public investment in military and reconstruction sectors would likely erode these profits and restore the stagnation characteristic of the late 2010s. Thus, peace — particularly under Western terms — represents not an opportunity but a threat to the new accumulation regime.

Although sanctions have inflicted damage in specific areas, particularly finance, technology and high-end manufacturing, Russian capitalism has, to a surprising extent, adapted to the new constraints. Many of the sanctions have been partially endogenised: they are no longer experienced simply as external shocks, but as part of the system’s operating logic.

Domestic producers have gained from the elimination of foreign competition, particularly in sectors where they were previously unable to compete. Capital and currency controls, imposed by the state in response to financial sanctions, have managed to stabilise outflows and preserve the ruble’s value. Parallel import schemes via China, Turkey, Central Asia and the Gulf have restored access to essential goods, including advanced technological components. In many cases, the state has absorbed the burden of adjustment, redistributing rents through subsidies and nationalisations that preserve elite interests.

War as an engine of regime stability

Sergey Aleksashenko, Vladislav Inozemtsev and Dmitry Nekrasov point out in their report Dictator’s Reliable Rear that the resilience of the Russian economy under sanctions and wartime pressure is not accidental but structurally grounded in a model of capital accumulation that functions increasingly well under conditions of confrontation. They highlight that profits in Russia today are not derived primarily from productivity gains or global competitiveness, but from state-controlled rent flows, preferential access to protected sectors, and the political consolidation of key industries. The war economy, in this view, has become internally coherent — one in which predictable returns, subdued elite rivalry and regime stability are tightly bound to the continuation of hostilities.

This logic creates strong structural disincentives for the cessation of conflict, especially under terms that would require territorial concessions, liberalisation or re-integration into Western-led institutions. Unlike the globalist accumulation model of the 2000s and early 2010s — which was premised on access to Western capital markets, real estate and offshore financial networks — the current regime is relatively insulated from Western volatility. For those now in command of state-connected enterprises, logistics monopolies and import-substituting industries, a prolonged or low-intensity conflict is not an existential threat but a stabilising condition.

This shift is rooted in a broader transformation of Russia’s class structure. The oligarchic elite that emerged in the 1990s and consolidated during the 2000s — reliant on Western capital, real estate and offshore havens — has been partially sidelined. Some lost access to their wealth through sanctions; others were absorbed into domesticated, state-aligned ventures. Their influence over accumulation strategies has diminished.

In their place, a new elite has taken shape: defense contractors, construction tycoons, sanctioned technocrats managing import-substituting sectors and regional bosses profiting from reconstruction in occupied territories. These actors are not embedded in global circuits of capital. Their fortunes depend on loyalty to the regime and continued access to wartime rents. A temporary truce — even one imposed by the Donald Trump administration — might reduce geopolitical risk, but it would also destabilise the domestic economic order that sustains them. The war has made them rich; peace could make them irrelevant.

The war has also taken on a broader function in the consolidation of political power. It serves not merely as an instrument of foreign policy, but as a domestic mechanism of elite cohesion and regime legitimation. Within this logic, support for the war becomes a loyalty test: political actors, businesspeople and even cultural figures are expected to demonstrate alignment with the state’s goals or face exclusion and repression.

War justifies authoritarian centralisation, suppresses dissent and allocates capital to favoured groups. It disciplines the elite and eliminates or neutralises internal competitors. In this context, even the idea of a “frozen conflict” that deescalates hostilities without resolving territorial issues may be seen as destabilising. It could reopen elite competition, embolden alternative factions — including the remnants of the pro-Western oligarchy — and undermine the ideological cohesion that the war effort currently supplies.

At the ideological level, the war has been framed by the regime as both a defensive measure against Western imperialism and a civilisational mission. This narrative has been deeply institutionalised, from media and education to official speeches and symbolic politics. Any concession — even one that does not involve formal territorial retreat — risks being read as betrayal. Such a move could demobilise supporters, invigorate nationalist hardliners and set a precedent for future Western demands regarding Crimea or other territories. Furthermore, even if sanctions relief were secured in exchange for a settlement, its long-term reliability is suspect. A future US administration may reverse any détente, as previous episodes of sanctions relief and rollback have shown.

Finally, the war economy is no longer dependent on Western capital or markets for its reproduction. Russia’s external orientation has shifted decisively toward China, India, Turkey and the broader Global South. Trade volumes with these partners have expanded significantly, particularly in the energy sector. Figure 5 shows hydrocarbon exports to China, India and Turkey surged between 2019–21 and in 2023, while exports to the European Union collapsed. Energy flows have been re-routed eastward and southward, with China now absorbing nearly as much as the EU once did, and India and Turkey emerging as key buyers.

At the same time, Russia has increased its participation in BRICS and alternative financial and political forums. These ties offer not only economic lifelines but also new arenas of accumulation, investment and diplomatic recognition. Western markets and institutions are no longer the sole gateway to growth and reproduction. This diversification reduces the strategic leverage of the West — even if it were united in offering sanctions relief — in influencing the behaviour of the Russian capitalist class.

At first glance, this eastward turn might suggest a transition toward the kind of delinking envisioned by Samir Amin — an attempt to restructure the economy around domestic reproduction rather than dependency on the global core. In my earlier article, I proposed (somewhat provocatively) that elements of the wartime economy — such as the expansion of basic industrial production and a degree of downward redistribution — appeared to carry pro-poor features, potentially signaling the beginnings of a self-centred development path.

However, research that Kagarlitsky and I subsequently conducted — building on Minqi Li’s methodology of tracking cross-border value transfers — suggests a more sobering reality. While the redirection of trade flows from the West to the East has reduced the scale of net value transfers out of Russia, these transfers remain persistently negative. The bulk of surplus value that once flowed to the West now accrues to China, Russia’s new central trading partner.

Importantly, this reorientation trend predates the full-scale war. In 2018, Russia’s oil exports to China nearly doubled following the commissioning of the second leg of the Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline, raising capacity from approximately 15 to 30 million tons annually. Meanwhile, exports to the West stagnated. The later launch of the Power of Siberia natural gas pipeline in December 2019 — designed to reach a capacity of 38 billions of cubic metres by 2025 — further institutionalised the eastward flow of strategic commodities

Kagarlitsky and I argue, following Giovanni Arrighi, that this is not a case of delinking but of re-Orientation: a shift in dependency from one centre to another. Rather than escaping the structural logic of global capitalism, Russia has re-embedded itself within a different core–periphery dynamic — this time with China at the centre. Moscow may aspire to become a hub in an “alternative globalisation,” but economically it remains on the receiving end of unequal exchange.

Aleksashenko and his colleagues note that Russia is not simply “falling into China’s embrace” (already evident, as China accounted for 33.8% of Russia’s foreign trade turnover in 2023 — a share comparable to that of the EU in the mid-2010s). Rather, Moscow is transforming into a centre of an “alternative model of globalisation,” operating outside the frameworks of Western-controlled institutions and established rules.

The very features that make the present system seemingly unsustainable from a Western or liberal economic viewpoint — lack of investment, technological stagnation, exclusion from Western capital — are what allow the regime to control the flow of capital, suppress internal dissent, and sustain elite loyalty. War spending functions as a tool of internal redistribution, channeling rents to politically compliant actors and crowding out autonomous capitalist initiatives.

De-escalation would, paradoxically, destabilise this arrangement by reintroducing competition, restoring the political relevance of marginalised oligarchs, and weakening the ideological glue that now binds the state and capital. Vladimir Medinsky, Kremlin’s chief negotiator with Ukraine, has recently invoked Peter the Great’s 21-year war with Sweden to stress that Russia is prepared to fight “forever” in Ukraine.

It is therefore unsurprising that more voices in Ukraine (such as General Valerii Zaluzhny) and the West (for example, former NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg) now speak in terms of a protracted conflict lasting not months but years — or even decades. While some actors may indeed see benefits in a prolonged standoff, such as expanded military-industrial activity or renewed geopolitical relevance, most view this trajectory with deep concern.

Paradoxically, however, many — including not only elites in Moscow but also observers in Western capitals — now perceive a low-intensity, contained conflict as more manageable and less destabilising than an unpredictable peace. Some Western analysts argue that the Russian economy will eventually succumb to fiscal exhaustion and demographic decline, while Ukrainian political and military elites increasingly recognise that the objective of a rapid and decisive military victory is no longer tenable. In this emerging consensus, strategic patience — through prolonged pressure, containment and attritional warfare — is seen as the most viable path forward.

This logic is mirrored in Moscow as well. As long as the economy avoids overheating and sanctions continue to be partially endogenised (as discussed earlier), the Russian leadership has little incentive to seek reconciliation. A controlled, relatively low-intensity war offers clear political and economic advantages: it sustains regime legitimacy, keeps Western pressure at bay, and consolidates the loyalty of the newly ascendant elite class. The material conditions of the war, rather than undermining the system, have been metabolised by it.

In this light, the war is not merely a geopolitical blunder or an ideological crusade. It has become a structurally functional component of Russia’s current capitalist order — serving as a mechanism of class cohesion, rent distribution and geopolitical realignment. As long as these functions remain intact and the costs contained, structural incentives will continue to favor prolonged confrontation over peace.

War as a structural feature, not a strategic mistake

This article has argued that Russia’s war in Ukraine is not simply a geopolitical miscalculation or ideological excess, but a structurally embedded feature of its capitalist accumulation regime. Faced with declining profitability, capital flight and external constraints, the system adapted through war-driven restructuring. A new elite emerged — rooted in defense, construction and import-substituting sectors — whose fortunes depend on continued conflict, not peace. Military Keynesianism, capital controls and rent redistribution stabilised accumulation and elite cohesion under siege conditions.

Rather than representing a rupture, this transformation refunctionalised existing features of Russian capitalism. The war economy absorbed sanctions and repurposed constraints into sources of domestic accumulation. Peace, especially under Western terms, would threaten this balance by reviving competition, weakening elite discipline and undermining the political legitimacy built on wartime mobilisation.

These findings challenge the liberal expectation that capitalism promotes peace through integration. The Russian case shows peripheral political capitalism can stabilise itself through confrontation, not despite it. War becomes not an interruption, but a mechanism of accumulation, class realignments and regime survival.

This does not mean that ideology and irrationality play no role. But as Kagarlitsky cautions in The Long Retreat: Strategies to Reverse the Decline of the Left, even when leaders appear to act irrationally, their madness “does not appear of its own accord, but develops as a side effect of the functioning of the system. Different social systems, cultures and political practices give rise to different manias.” In other words, political misjudgments — even extreme ones — are systemically conditioned. They emerge not outside of structure, but from within it.

In this sense, Russia may not be exceptional. Other states facing similar crises — sanctioned, marginalised or stagnating — may also turn to war as a political and economic strategy. The Russian experience should serve not only as a warning but as a framework for understanding how capitalism can endure, and even thrive, under conditions of sustained conflict.