Class analysis and Russian imperialism: A response to Ilya Matveev

In his interview, “Political imperialism, Putin’s Russia, and the need for a global left alternative,” Ilya Matveev suggests that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was motivated almost entirely by Vladimir Putin’s ideological fears and concerns for his regime’s preservation. Matveev contends these actions lacked economic rationale and were driven by ideology alone. While this interpretation has some merit, it oversimplifies the structural forces at play. By focusing primarily on ideology and Putin’s personal motivations, Matveev overlooks broader class dynamics and the material interests of Russia’s capitalist class, which are crucial to understanding Russia’s post-2014 foreign policy.

Karl Marx argued that to fully grasp the actions of a state, one must first examine the economic base — specifically the interests of the ruling class. A class analysis reveals that the war is not simply the result of geopolitical fears but reflects the economic interests of Russia’s capitalist class. The invasion of Ukraine is part of a broader interplay between the capitalist logic of profit maximisation and the power logic of geopolitical control, both of which shape Russia’s imperialist ambitions.

The limitations of the individual-centric explanation

Matveev claims Russia’s post-2014 actions, including the annexation of Crimea, can be understood through Putin’s ideological fear of Western regime change. He argues: “There was no economic logic to annexing Crimea.” However, as Marx pointed out, the state functions as a tool of the ruling class, and its actions must be understood within the context of the economic system that underpins it. By focusing solely on ideology, Matveev overlooks the material interests of Russia’s political capitalists, who have profited from the annexation and the war.

Boris Kagarlitsky notes in his analysis of Russia’s peripheral imperialism that the ruling class is not simply motivated by nationalistic or ideological concerns. Crimea’s annexation is not an isolated case but part of a broader economic strategy. This strategy reflects the interests of Russia’s political capitalist class, which has exploited the war for profit opportunities, particularly in state-led projects and infrastructure development. State contracts for energy, construction, and defence activities have proliferated in the newly annexed territories, providing lucrative avenues for capital accumulation.

Economic rationale for the invasion of Ukraine

While Matveev emphasises the ideological motives behind Russia’s actions, the economic rationale is equally critical. Samir Amin has argued that imperialism is often driven by the need for capital to find new outlets for investment to counter the effects of over-accumulation in the imperialist centre. The invasion of Ukraine provided precisely these opportunities for Russia’s political capitalist class, a common ruling elite in the post-Soviet space as argued, for example, by Volodymyr Ishchenko. Being in essence “political capitalists,” the ruling class is heavily dependent on state contracts and public resources for their wealth, and additional expenditures on territorial expansion are seen as investments that open new channels for profit-making.

Military Keynesianism, characteristic of the Russian economy in the past two years, far from depriving capitalists from their profits, has created new profitable investment opportunities. The invasion has spurred significant investments in infrastructure projects, particularly in transportation, energy, and public construction, with Russian firms benefiting from state contracts. This highlights the capitalist logic behind the war: the Russian state, controlled by the political capitalists, redirects public funds into sectors dominated by the ruling class, ensuring continued capital accumulation while at the same time counteracting the key feature of capitalism identified by Marx — the falling rate of profit. Long-term government contracts guaranteeing stable demand and profits stabilise the capitalist system.

This is even more true in the case of the military-industrial complex. The conflict has generated significant profit opportunities for Russia’s military-industrial complex, as defence spending and state contracts for military production have surged. The sheer number of recent corruption cases opened against Russian defence officials (including in the top echelons) and military suppliers gives an idea of just how much money has flooded into the military-industrial complex, overwhelming its capacity to absorb it efficiently. As vast sums of capital are funnelled into defence contracts, the opportunities for graft, kickbacks, and embezzlement multiply, revealing the system’s inability to manage such huge inflows without leakages.

These corruption scandals are not merely incidental but symptomatic of a larger problem: the saturation of the military sector with surplus capital that far exceeds its productive or strategic needs. In many ways, this mirrors Paul A Baran and Paul Sweezy’s concept of “ waste spending,” where the state directs resources into unproductive sectors as a way to stabilise the economy. Inflated prices and military spending inefficiencies become avenues for the ruling class to extract profits, even as corruption erodes the intended military objectives. This overflow of capital, rather than strengthening Russia’s military capabilities, often serves the interests of political capitalists who benefit from the bloated system.

(Of course, this is also true for the Western military-industrial complex, which is thriving on a surge of new military orders. US Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell publicly stated that military aid to Ukraine has allowed the US to develop cutting-edge technology that will be crucial in future global competition, especially against rivals such as Russia and China, while boosting US job creation through increased production for defence contracts.)

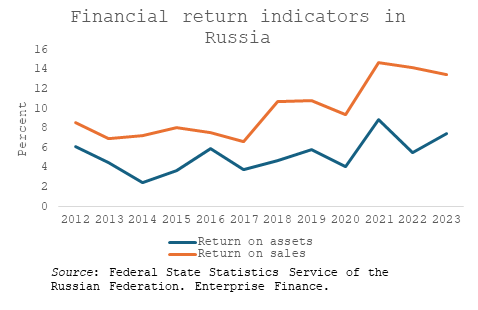

These factors show that, as Marx argued, the economic base — capital accumulation — is driving the superstructure, including the state’s imperialist actions. Indicators of financial returns in Russia reached their highest level in a decade in 2021 and have remained there since. Return on sales jumped from about 9% to almost 15%. Far from acting on ideological whims, the Russian ruling class is pursuing material interests through territorial expansion.

Class interests in Russia and Ukraine: A divergence in capital accumulation

To better understand Russia’s actions, it is also necessary to examine the differing patterns of capital accumulation in Russia and Ukraine, as highlighted by Ishchenko. He points to the conflict being rooted in contradictions within the Ukrainian national bourgeoisie, who are divided by their attitudes toward transnational capital: the accommodationist faction and the faction of political capitalists. I argue, however, that this division is grounded in material conditions, specifically the types of assets owned by these groups. The accommodationist faction relies on more mobile financial capital, whereas the other faction is tied to less mobile industrial capital, which is more vulnerable to competition from Western capital. Although both factions are ultimately political capitalists, given the origins of their wealth, the second group is less dependent on state patronage. This class struggle reflects broader trends in capital mobility and varying degrees of state dependency.

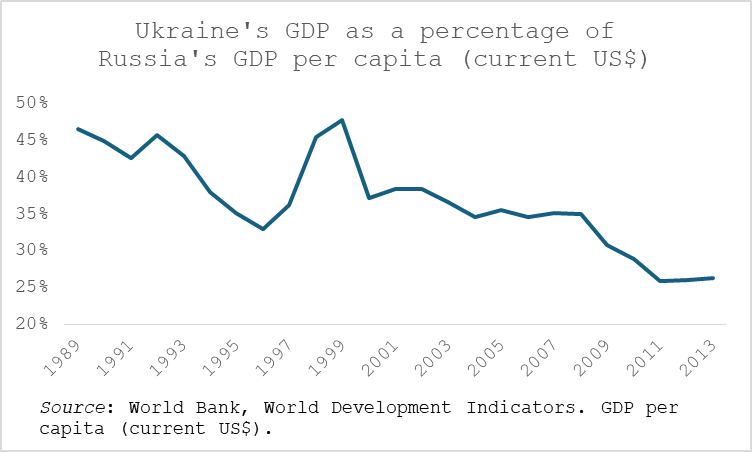

In Russia, rapid growth in the 2000s and early 2010s (averaging 5.2% annually between 1999 and 2014), particularly in the energy sector, generated substantial capital surpluses that needed reinvestment. But profitable investment opportunities were in short supply (save for a few extractive industries and real estate development). This explains, among other things, the huge capital flight from Russia. Russian capitalists looked to former Soviet republics, including Ukraine, as investment outlets. However, the growing presence of Western capital in these regions threatened Russian interests. Amin argued that the global expansion of imperialist powers often provokes resistance from local capitalist classes, who seek to protect their spheres of influence. The annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine, therefore, reflect the Russian capitalist class’s need to protect its interests in these regions.

In contrast, Ukraine’s lower growth rates meant its financial bourgeoisie had accumulated less capital. Ukrainian capitalists, particularly those with ties to mobile financial capital, were more inclined to cooperate with Western capital, as a way to safeguard their investments. This divergence in capital accumulation patterns explains why Russia chose confrontation while Ukrainian elites sought Western integration.

Russia’s rupture with the West: A class-driven decision

Matveev suggests that the rupture between Russia and the West in 2014 was driven by Putin’s ideological concerns. However, as Claudio Katz points out in his analysis of global imperialism, different forms of imperialism emerge based on the specific class configurations of each country. In Russia’s case, the rupture was not solely the result of Putin’s ideological preferences but reflected deeper class dynamics.

Before 2014, Russian and Western capitalists cooperated profitably, as Matveev acknowledges. However, Western capital’s growing influence in Ukraine and other post-Soviet states increasingly threatened Russian capital’s long-term interests. Crimea’s annexation and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine were strategic moves by the Russian ruling class to protect its dominance in the region, particularly in sectors such as energy and infrastructure, which were vulnerable to Western encroachment.

Katz argues that peripheral imperialism often arises when the local ruling class, facing competition from stronger powers, adopts more aggressive postures to defend its economic interests. Russia’s actions reflect this dynamic, as its ruling class sought to delink from the West in response to the perceived threat posed by Western capital’s expansion.

Why Russia did not continue cooperation with Western capital

Unlike the Ukrainian financial bourgeoisie, which welcomed cooperation with Western capital due to its reliance on mobile financial investments, Russian capitalists were tied to less mobile, strategic industries, such as energy and defence. Marx explained that industries dependent on immobile capital require greater state protection to secure long-term profitability. For Russian capitalists, cooperation with Western capital would have undermined their strategic industries, particularly as Western firms began to dominate sectors crucial to Russia’s economy.

Kagarlitsky has noted that Russia’s ruling class faced growing pressure to maintain state control over its key industries, especially in the face of NATO expansion and Western encroachment. Crimea’s annexation and the broader rupture with the West were therefore driven by economic concerns, not simply ideological ones. Russian capitalists, particularly those tied to energy and defence, viewed confrontation with the West as necessary to protect their economic dominance.

The dialectical interplay of capitalist and power logics

While the economic motives behind Russia’s actions in Ukraine are clear, it is essential to consider the dialectical relationship between the capitalist logic of profit maximisation and the geopolitical (or territorial) logic of state control. Giovanni Arrighi pointed out in The Long Twentieth Century that, historically, these logics have not operated in isolation but rather in relation to one another. While Matveev introduces the idea of “political imperialism” driven by territorial logic (the logic of power), it is crucial to emphasise that for Arrighi, the territorial logic is often in service to, and subordinate to, the capitalist logic. Even when geopolitical strategies seem to contradict short-term economic interests, they typically create conditions that safeguard long-term capital accumulation.

Arrighi’s analysis aligns with Lenin’s argument in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, where imperialist expansion is presented as a necessary outcome of capitalist development. Lenin emphasised that imperialism is driven by economic needs — particularly the search for new markets and investment opportunities as capital over-accumulates in core capitalist countries. In this sense, imperialist territorial expansion, whether by trade or conquest, is fundamentally tied to the financial logic of the ruling class. Lenin argued that the export of capital and expansion of financial control through imperialism are ways for capital to overcome domestic limitations, further illustrating how economic imperatives drive geopolitical ambitions.

In Russia’s case, the war in Ukraine exemplifies this dialectical interplay. The capitalist logic is evident in the pursuit of profit through energy control, infrastructure projects, and defence contracts. Simultaneously, the power logic manifests in Russia’s effort to maintain its geopolitical influence in the post-Soviet space. However, as Arrighi and Lenin both argue, territorial expansion is rarely an end in itself. The ultimate goal is to secure the material interests of the ruling class, ensuring access to resources and markets that are vital for continued capital accumulation. Arrighi pointed out that the main reason for European expansionist imperialism in the 18-19th century was the desire to retrieve the purchasing power that was relentlessly draining from West to East and to restore economic balance. While it may be analytically useful to speak of “political imperialism,” it should not obscure the fact that geopolitical strategies are usually subordinate to the more universal logic of capital.

The class dynamics behind Russian imperialism

Matveev’s argument that the invasion of Ukraine is primarily ideologically driven fails to account for the economic rationale driving the actions of the Russian ruling class. Marx, Amin, and Kagarlitsky have all argued that imperialism is always rooted in the material interests of the capitalist class — and the war in Ukraine is no exception. The conflict is shaped by both the capitalist logic of profit maximisation and the power logic of geopolitical control, which are dialectically interconnected.

By understanding the invasion through a class analysis, it becomes clear that the war is not simply the result of ideological fears — let alone the poorly thought-through decision of one individual, however powerful — but that it is driven by the economic interests of Russia’s political capitalists. The rupture with the West was not a spontaneous decision based on Putin’s personal ideology, but a strategic move by the ruling class to protect its long-term capital accumulation. These dynamics suggest that the conflict is unlikely to end with Putin’s departure, as the structural forces shaping Russian imperialism will continue to guide the state’s actions.

But this does not mean that ruling classes never make mistakes while pursuing what they deem is their best interests. History has proven the opposite on numerous occasions. Had the ruling class always chosen the optimal survival decision, there would have been no place for revolutions and other social upheavals. This is what Marxism is essentially about: understanding that the capitalist system is riddled with contradictions, driven by the conflict between the ruling class’s pursuit of profit and the inherent instability of capital accumulation. But we should always keep in mind what Friedrich Engels said about the complex interplay of material and ideological factors in paving the way for history:

According to the Materialist Conception of History, the factor which is in the last instance decisive in history is the production and reproduction of actual life. More than this neither Marx nor myself ever claimed. If now someone has distorted the meaning in such a way that the economic factor is the only decisive one, this man has changed the above proposition into an abstract, absurd phrase which says nothing.

In Russia’s case, while the political capitalists have strategically pursued their interests through imperialist actions, including the invasion of Ukraine, this does not guarantee long-term success or stability. The war, driven by a fusion of economic and ideological motives, could exacerbate internal tensions, fuel popular discontent, and strain Russia’s economy in unforeseen ways. As Marx pointed out, the very actions taken by the ruling class to preserve its dominance can sow the seeds of future crises — and ultimately destabilise the system they aim to uphold.